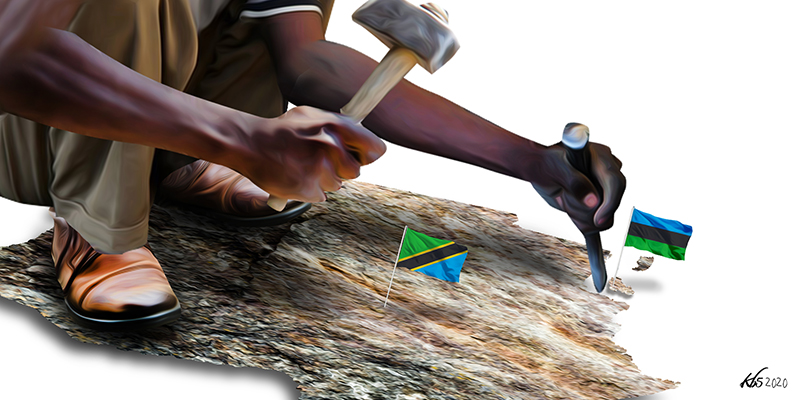

The union between Tanganyika and Zanzibar – the contentious two-tier government system that Tanzania adopted – has been riddled with a number of complaints (commonly referred to in Kiswahili as kero za muungano or grievances of the union) right from its formation on April 22, 1964. None of these complaints, however, have been nearly as controversial as Zanzibar’s de facto inability to enter into international agreements. (Zanzibar’s failed attempt in late 1992, for instance, to unilaterally join the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) almost broke the union.) However, the desire among Zanzibaris to have this arrangement overturned across the political spectrum has never wavered and nothing could have demonstrated the arrangement’s detriments to Zanzibar’s development as much as the COVID-19 pandemic.

There is no shortage of literature on the history of the union between Tanganyika and Zanzibar, especially on its motivations. Various people, including journalists, historians, and social scientists, have tried to document the historical development regarded by some as one of the most enduring legacies of Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, the co-founding father of the modern Tanzanian state.

I’m too young to claim any expertise on the subject of the union (which, really, is older than my father), but as I write this I can vividly picture my high school history teacher, a blackboard behind his back, haranguing the class on how the union was conceived for the Zanzibaris’ own benefit, mainly security, and especially in preventing the return of the “Arab Sultanate” that had been overthrown in 1964. Only later would I come to learn other motivations behind the union: first, an attempt by Mwalimu to realise the Pan-Africanist dream, and second, a deliberate effort by the world’s only superpower, the United States, in the midst of Cold War politics, to prevent the emergence of “another Cuba” in the region.

How the union came about

People who are not familiar with Tanzania’s political system should understand that Tanzania’s union is a two-tier government system where there’s the semi-autonomous government of Zanzibar, known as the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar, currently under President Ali Mohamed Shein, which handles all non-union matters, and the union government, known as the Government of the United Republic of Tanzania, currently under President John Magufuli, which, contentiously, handles both union and non-union matters.

The uniting of two distinctly divergent people, both culturally (predominantly Muslim Zanzibar versus largely Christian Tanganyika) and ideologically (progressive Zanzibar versus conservative Tanganyika) took place at breakneck speed, hardly three months after the controversial Zanzibar Revolution of January 12, 1964. This denied the people from both sides of the union any chance to express their views on the decisions made by their leaders, leaving some sceptical observers doubtful of the union’s true intentions and thus laying a fertile ground for the disagreements that were to follow.

In the rush to realise the union, the Articles of the Union – the treaty that effected the union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar – ended up being ratified only by Tanganyika’s Parliament on April 26, 1964, contrary to the initial agreement that the union also had to be ratified by the Zanzibar Revolutionary Council that was formed immediately after the revolution and which functioned both as a legislative and executive arm of the state.

What’s worse, nobody has ever seen the original copy of the Articles of the Union that carries the signatures of the founding fathers Mwalimu Julius Nyerere and Sheikh Abeid Aman Karume, the first president of Zanzibar. This is one of the thorniest issues in the whole discourse on the union between Tanganyika and Zanzibar.

In the rush to realise the union, the Articles of the Union – the treaty that effected the union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar – ended up being ratified only by Tanganyika’s Parliament on April 26, 1964, contrary to the initial agreement that the union also had to be ratified by the Zanzibar Revolutionary Council…

But that’s not the only thorny issue; the other is the arbitrary increase in the number of issues handled by the union, something that makes Zanzibar progressively less autonomous while increasing the powers of its partner, Tanganyika (which, to the Zanzibaris’ chagrin, now functions as Tanzania). This enables the government to meddle in Zanzibar’s local affairs, the most notorious form of meddling being deciding which political party will lead in the isles. This complicates the archipelago’s efforts in defining its developmental path as well as dealing with issues of immense significance to its people, as the COVID-19 experience has demonstrated.

While Zanzibar is expected to handle the health of its people on its own, in the process of doing so it cannot ask for regional or international support. This is because, according to the Constitution, health is a non-union matter but regional and international cooperation is a union one. This unfortunate arrangement has naturally meant that were Zanzibar in need of any support from, say, the World Health Organization (WHO), or from any other potential donor in its efforts to fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, or to carry out any development initiative, it has to request it through the union government, which reserves the sole right to decide whether the request can go forward. Nothing makes Zanzibaris as disillusioned about the union as this arrangement does, and it is against this background that several demands for the restructuring of the union have been made.

Two very different approaches

Regarding COVID-19, right from the beginning, Zanzibar, a country of about 1.3 million people, and characterised by a strong communal spirit, took what seemed to be a completely different approach from that of the government of John Magufuli in its efforts to deal with the pandemic. It first reported cases on the isles on March 19, a time when the union government was still trying to figure out how to confront the public about the deadly virus, choosing instead to deny the people important information. As soon as it started to confirm its first coronavirus case, Zanzibar issued an update to its citizens and the world in general on the status of the pandemic there, earning it some admiration from some of Tanzania’s health experts.

On March 21, the Zanzibar government suspended all international flights entering the isles, a decision followed almost three weeks later, on April 13, by its union counterpart. Zanzibar even went one step further in an attempt to contain the spread of the pandemic by shutting down all 478 tourist hotels on the isles. This significantly affected its tourism sector, the lifeblood of the archipelago’s economy, which accounts for almost 80 per cent of its annual foreign income.

Almost a week after the union government announced, on April 28, that only 16 people had died of COVID-19, Zanzibar released an update showing that 32 people had died of the disease, something that made critics question the union government’s figures.

The difference in the approaches to dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic has more to do with the attitude of their respective leaders. While President Shein appreciated the magnitude of the pandemic right from the beginning, and thus took strong measures to contain it, his union counterpart, President Magufuli, on the other hand, did not view the pandemic as a threat. He even advised Tanzanians to go on with their business. While Shein’s government was postponing a major religious event to contain the spread of the fatal virus, the union government organised one. While Shein used every opportunity to urge people to protect themselves against COVID-19 by regularly washing their hands, using sanitisers and wearing masks (even making the latter directive mandatory, with he himself wearing it to set an example to his people), his union counterpart never wore one and was busy advising people to use steam inhalation therapy, saying it cures the disease in spite of health experts advising otherwise. In other words, while Zanzibar’s approach to COVID-19 was informed by the archipelago’s authorities’ willingness to trust science, Magufuli’s approach was informed by something quite the opposite: superstition and quackery.

These steps notwithstanding, there are limits to Zanzibar’s efforts to dealing with the priorities of its people, as highlighted above, thanks to both the current structure of the union as well as clientelism that characterises Zanzibar’s ruling elites, which tend to see their union counterparts (who happen to belong in the same party, the ruling Chama cha Mapinduzi [CCM]) as their patrons and thus are only free to pursue a particular path only to the extent that their patrons on the mainland can allow them. For example, Zanzibar stopped issuing updates on the COVID-19 trend shortly after the union government did so in the wake of the temporal closure of the national laboratory where COVID-19 tests used to be conducted to pave way for an investigation following allegations, among many others, that the lab’s technicians were conspiring with “imperialists” to portray Tanzania negatively by releasing more positive COVID-19 cases.

In other words, while Zanzibar’s approach to COVID-19 was informed by the archipelago’s authorities’ willingness to trust science, Magufuli’s approach was informed by something quite the opposite: superstition and quackery.

To understand this complexity, one must understand how political leadership has always been obtained in Zanzibar, or, to put it differently, how CCM has always ended “winning” elections in the archipelago: it’s through a sponsorship from the union government and its security apparatus. Following pressure from the union government, for example, Zanzibar’s electoral body was forced to annul the 2015 election results for the president of Zanzibar and members of the House of Representatives, the archipelago’s legislative body, after initial results had shown that CCM, which has ruled both Zanzibar and the mainland since independence, had lost to the isles’ main opposition party, the Civic United Front (CUF). This has forced the Zanzibar government, which the opposition in Tanzania deems to be “illegitimate”, to feel like it has a debt to pay to the union government. (Jecha Salim Jecha, the then chair of the Zanzibar electoral body who was responsible for the 2015 annulment of the isles’ election, surprised many in Tanzania and beyond when he became one of more than a dozen CCM members who have declared their intention to run for the isles’ presidency on the party’s ticket.)

Zanzibar’s relatively better performance in fighting COVID-19 earned it some praise in the court of public opinion, with some even organising online fundraising to support the country in its war against the deadly virus. The seriousness shown by Zanzibar’s political leadership during the pandemic also made the archipelago a potential beneficiary of a number of international rescue aid packages available for needy countries, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s COVID-19 Emergency Financial Assistance. But that never happened, thanks to the current structure of the union. Apparently, the union government applied for the IMF’s rescue package but it was denied on several grounds, including the government’s decision to give inaccurate statistics on the budget it claimed to have spent in dealing with the COVID-19. The IMF’s Tanzania representative, Jens Reinke, told African Business that “the government doesn’t see the crisis as that big an issue” (Tanzania was ultimately able to secure about $14.3 million debt relief from the IMF’s Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust to cover the country’s debt service from June 10 to October 13.)

The Black Lives Matter movement might have popularised the phrase “I can’t breathe”, but it did not coin it. Neither did George Floyd, the unarmed black man who said these words when his neck was under the knee of a white police officer. Zanzibaris used the phrase long before it became a global rallying cry for racial justice. The only difference is that they have been using it in the plural form, “We can’t breathe”, or “Hatupumui” in Kiswahili.

Zanzibaris have for years been demanding for the restructuring of the union. They want a three-tier government system (that is, the government of Zanzibar, of Tanganyika and that of the United Republic) so that they can have more room than they have now to decide their own affairs and direct their own development path. The union government has deployed every available weapon in its arsenal to quash these demands, even arresting the movement’s leaders, and detaining them over trumped-up terrorism charges. Tanzania’s resolve to not let Zanzibaris “breathe” has turned it into a de facto occupying force in the archipelago that imposes its will on the people of Zanzibar and interferes in every aspect of the people’s lives. As shown above, it even decides which political party can govern the isles.

The COVID-19 pandemic has taught us numerous unforgettable lessons. However, the most important of these lessons for Zanzibaris is that they can be better off without the union as it is currently constituted. It is not an overstatement, therefore, to conclude that the disease has strengthened their resolve to achieve the right to self-determination.