The tension was evident, untouchable, but abundant. Everyone spoke with unmistakable anger. It was approaching 11.00 p.m. and for hours we listened to community members who took turns to narrate to us the harrowing experiences the Borana community had gone through at the hands of well-trained rangers and raiders from the Samburu community. This had gone on since 2006 when the Biliqo-Bulesa Conservancy was formed.

“We were forced to collect the information at night after word went round that the Northern Rangelands Trust had earlier mobilised its supporters to unleash chaos during a meeting called the following day to discuss its operations in the Conservancy,” said Al-Amin Kimathi, a renowned human rights activist. . After taking dinner out in the open, the team gathered in a makeshift shelter eager to listen to members of the community. And they had prepared well. Some had come with written notes and used torches to read through them.

“The organisation employed the carrot-and-stick tactic used across Africa for centuries by Europeans to colonise, control, exploit and dominate people on the continent. NRT started off by contacting and sweet-talking influential personalities within the community who it later deployed to convince fellow community members of the benefits they stood to gain from the conservancy,” said Najar Nyakio Munyinyi, a consultant on indigenous land rights.

“Ile ndovu tuliyoambiwa tutakua tukiikamua sasa imekua ya kutumaliza” (We were told that we will be benefiting from wildlife conservation, but instead we have been losing our lives), said Sheikh Dabbaso Ali Dogo, the former chairman of the Conservancy Board. Dogo added that before the conservancy was formed, top officials of NRT, including its founder, Ian Craig, had made a raft of promises to the community.

“The organisation employed the carrot-and-stick tactic used across Africa for centuries by Europeans to colonise, control, exploit and dominate people on the continent. NRT started off by contacting and sweet-talking influential personalities within the community who it later deployed to convince fellow community members of the benefits they stood to gain from the conservancy,” said Najar Nyakio Munyinyi, a consultant on indigenous land rights.

Among those selected was Jaarso Golicha Gaade, a former councilor with the defunct Isiolo County Council and now an employee of NRT. With other elders, Gaade was hosted by Craig at Lewa Conservancy in Laikipia in 2006. Craig then asked the initial group of elders to identify fellow elders who could join them in coaxing the rest of the community members to accept the idea of the Conservancy.

After being promised goodies, the latter then organised seminars during which the formation of the Conservancy was discussed. “NRT promised the communities a complete halt to the long-running insecurity and cattle-rustling incidents as well as lasting peace between it and the neighbouring Samburu, Turkana and Rendille communities,” said Retired Major Jillo Dima, an elder in the community. Jillo added that to make this happen, NRT promised to finance the construction of an institution for morans in the area. He says that the organisation also made other promises related to employment of young men as rangers and said that they would not only be protecting wildlife but also members of the community. It would also invest Sh50 million on a project identified by members of the first Conservancy Board, and income from tourism activities in the Conservancy.

“With the promises in mind, the community needed no more coaxing; it soon agreed to commit hundreds of thousands of its pasturelands for conservation purposes. The 364,000-hectare Conservancy was formed in 2006 following the ‘signing’ of an agreement between the community and the NRT.” He expressed disappointment that the agreement has remained secret for over the 13 years the Conservancy has been in existence, adding that it was odd that all the people, including former board members, “have neither seen the agreement nor were they aware of its provisions”.

(Our attempt to interview relevant officials of NRT did not bear fruits. They did not get back to us even after sending questions to them.)

Members of the community reported that apart from giving the Conservancy a vehicle, constructing two classrooms, a mud-walled nursery school and teachers’ houses and employing a number of rangers, the NRT has reneged on most other promises. To make matters worse, NRT went out of its way to worsen the plight of the community and unilaterally makes all the decisions. For instance, we learned that the organisation engineered the sacking and replacement of members of the first board after they demanded to know what came of the promises made to the community. Those interviewed added that finances meant for the Conservancy were banked in an NRT account and that the Conservancy has only held two annual general meetings since it was formed. Further, they said that past and current Conservancy board members have no powers and do not even know what income was earned by the Conservancy.

It is not a wonder that the community later resolved, in a meeting called by elected leaders and the Borana Council of Elders, to kick NRT out of Isiolo County; a resolution that is yet to be fully implemented.

‘Kenya ‘B’ and the Community Land Act

As part of Isiolo County, the land in Biliqo-Bulesa is just a small proportion of the more than 60 per cent of the country where land adjudication has hardly started. So anyone with the financial muscle and the ability to command the backing of top political kingpins in the country can lay claim to vast tracts of land there and thereby disinherit communities, some of whom have inhabited the region since the 10th century.

It is important to appreciate that the goings-on at the mammoth-sized conservancy is part of what happens in the section of the country now called, in Kenyan parlance, “Kenya B”. This is a vast region in the country whose residents have suffered neglect and open discrimination since the geographical entity now called Kenya was configured by the British colonisers. It is a region that seems to have remained in the peripheries of the subconscious of many a policy maker and politician who’ve run this country since independence. As Dr Nene Mburu says in the book Bandits on the Border: The Last Frontier in the Search for Somali Unity, this is “one half of Kenya which the other half knows nothing about and seems to care for even less.”

As part of Isiolo County, the land in Biliqo-Bulesa is just a small proportion of the more than 60 per cent of the country where land adjudication has hardly started. So anyone with the financial muscle and the ability to command the backing of top political kingpins in the country can lay claim to vast tracts of land there and thereby disinherit communities, some of whom have inhabited the region since the 10th century. The land conundrum there is now compounded by the decision to put up mega-schemes, such as LAPPSET and other Vision 2030 projects that continue to take up vast tracts of the community land.

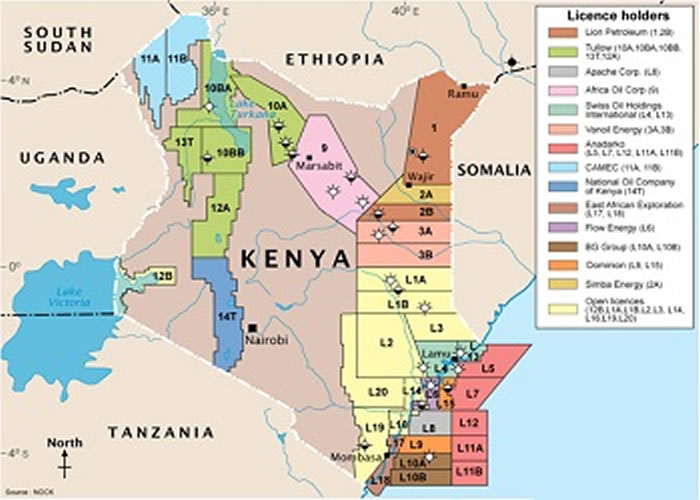

However, the seemingly desolate and apparent economically underdeveloped region covers more than half of Kenya’s total land area and has vast wealth buried in the soil. The presence of mineral wealth is confirmed by a map of oil blocks in Kenya that criss-cross Isiolo and other arid and semi-arid lands (ASAL) counties.

On paper, the land in Isiolo and elsewhere in the north is protected by the Community Land Act. This Act gives pastoral communities the right to govern their land with full recognition of their ancestral heritage and unique governance and livelihoods systems. It recognises, protects and provides for the registration of community land rights; the administration and management of such lands; and titling and conversion of community land. It also provides for the management of the environment and natural resources on community land and the resolution of disputes and accommodates the customs and practices of pastoral communities relating to land.

However, although this piece of legislation became part of Kenyan law in 2016, the process of developing regulations for its implementation have been frustrated by powerful people in government for their own ends. At the same time, little or no effort has been made to raise the awareness of members of the pastoral communities on the provisions of the Act. Further, the National Land Commission and the relevant county governments are yet to initiate a process that would lead to registration of community land and implementation of this law. This has given organisations, such as the NRT, adequate room to manipulate communities for their own benefit.

It is no wonder that NRT had gone ahead to unilaterally identify sites for the construction of tourism facilities that are located in areas that are key for the survival of the livestock-based economy in Biliqo-Bulesa and the entire Charri Rangeland. These include the Baballa Camp that is set to be put up along an animal movement route close to the Ewaso Nyiro River, the Maddo Gurba Huqqa, which is close to a community shallow well, and Sabarwawa, an area where the water table is quite shallow. Others are in Nyachiis, which was previously used by the community for traditional naming ceremonies, and Kuro-Bisaan Owwo, a hot spring whose water has medicinal properties for both humans and livestock – a place where the NRT had planned to set up a spa for tourists. “We have resisted the takeover of these sites by NRT,” said Jillo.

Deliberate schemes

There are those who believe that the failure to start the land adjudication process in Isiolo and the counties of Marsabit, Moyale, Garissa, Wajir and Mandera, and the marginalisation and deprivation in the erstwhile Northern Frontier District (NFD) have been deliberate schemes by all the governments that have run Kenya since the colonial period. Their main aim, it is said, is to keep the lands open for all manner of activities that have largely been injurious to the environment as well as to the local residents and their economic lifelines. For instance, the colonial government arbitrarily partitioned – and thereby greatly disrupted – the rhythm of life and especially the traditional pastoral way of life in the north. This went hand in hand with the establishment of what Dr Nene Mburu calls “impracticable administrative arrangements”.

The colonial government did little other than setting up military installations there, taxing the pastoralists as well as quarantining animal movements that curtailed the traditional trade in livestock. It also enacted discriminatory laws, such as the District Ordinance of 1902, declared Isiolo a closed district in 1926, and restricted the movement of residents under The Special Districts Ordinance of 1934. “This legislation regulated non-resident travel into the districts,” writes Dr Mburu who concludes that the net effect of the discriminatory policies was to create an “iron curtain” that isolated the north from the rest of Kenya.

Sadly, successive post-independence governments have not shown, in policy and actions, that they were opposed to the colonial policy. If anything, the first post-independence government of Jomo Kenyatta continued the colonial policy of discrimination and neglect. Kenyatta waged war against a determined Somali nationalism. This was after failing to reach an agreement over whether NDF was to be part of Kenya or Somalia during the three Lancaster House Conferences on 1961, 1962 and 1963. Between 1963 and 1968, Kenya deployed its military to fight off Shifta guerillas out to enforce the secession of the NFD from the new republic.

Isiolo’s hidden wealth

Isiolo is dominated by members of the Borana community who have continued to lose their land over the years. According to Dr Mburu, the community was historically used as a convenient human barricade, or buffer, by Ethiopia and Britain against the expansionist tendencies of other communities. For instance, he says that different Ethiopian kings used the Borana country to check the influence of European penetration into Abyssinia’s interior and to contain Somali expansion northwards from the NFD and western Somalia into Ethiopia. And just like the Kenya government has failed to do since the colonial period, Ethiopia merely used the Borana community but was not interested in governing its homeland effectively.This gave the Somali an opportunity to consolidate their westwards expansion into the NFD. Dr Mburu says that by 1880, the Somali had forcefully driven the Borana into Moyale and southwards out of the El-Wak wells, forcing them further westwards into Marsabit, Isiolo and parts of Wajir.

Although the attractiveness of Isiolo and other parts of the north appears to have being missed by policy makers, it is not lost on the NRT and the vested interests it represents. True, the region has a harsh environment with hot and dry habitats dominated by low-lying terrain, acacia trees, shrubs and isolated dwarf bush grasslands. The county has conditions that are quite uncomfortable, especially for people inhabiting the highlands areas of Kenya, where it is much cooler. Whenever they fall, the rains there are low; there’s hardly a place that gets more than 500 mm of rain. And besides the Tana and Ewaso Nyiro to the south as well as River Dauwa to the north, Isiolo and other counties in the entire region have few other permanent water sources.

However, the seemingly desolate and apparent economically underdeveloped region covers more than half of Kenya’s total land area and has vast wealth buried in the soil. The presence of mineral wealth is confirmed by a map of oil blocks in Kenya that criss-cross Isiolo and other arid and semi-arid lands (ASAL) counties. Indeed, the presence of mineral wealth in Isiolo and other areas of Kenya was confirmed by the Russian ambassador in 2003, who revealed publicly that by the 1940s, Russians had known the minerals Kenya has. What the ambassador did not reveal then was that the British had contracted Russian geologists to explore and map out mineral occurrence in Kenya.

The NRT-mineral connection becomes vivid if one was to overlay the map of the 35 conservancies under the organisation and the minerals-occurrence map of Kenya. Whether this is by coincidence or not is hard to ascertain. However, it is important to note that the NRT conservancies happen to be in the same areas suspected to have the greatest proportion of mineral wealth in Kenya.

Around the time the Russian ambassador made the claim, many keen Kenyans were surprised when mineral deposits started “popping out” all over the country. For instance, it was around the same time that the prolonged controversy over the titanium deposits in Kwale started. Further, word started spreading that Isiolo has significant deposits of iron ore, gemstones and other mineralsm, as well as vast amounts of water in the Merti aquifer. This was decades after Kenyan school children started being taught about the lack of minerals in the sub-soils of the country in geography lessons! What became interesting too was that the greatest number of companies that have since received prospecting or mining permits for oil, titanium and other minerals are either British or belong to the British in the Australian and Canadian diasporas.

The mineral-conservation nexus

It is easy to miss the connection between conservation and mineral occurrence in the country. It is also easy to miss the nexus between the ongoing quest to secure vast tracts of land, ostensibly for conservation purposes, and the confirmed mineral wealth in Isiolo and other counties in the north. But keen observers have noted an interesting financial camaraderie between the NRT and certain mining concerns. For instance, according to reports, Tullow Oil gave NRT a whopping $11.5 million (Sh1.15 billion) to NRT in 2013 to start six conservancies in Turkana, a county that has little or no wildlife. “It is not a wonder that many people have expressed suspicions that by donating so generously to NRT, Tullow Oil wanted the organisation to help it secure lands that are rich in oil deposits,” said Ms Munyinyi. However, as media reports showed, the operations of NRT in Turkana were curtailed to a great extent after the Joseph Nanok-led county government kicked the organisation out of the county in 2014.

The NRT-mineral connection becomes vivid if one was to overlay the map of the 35 conservancies under the organisation and the minerals-occurrence map of Kenya. Whether this is by coincidence or not is hard to ascertain.

However, it is important to note that the NRT conservancies happen to be in the same areas suspected to have the greatest proportion of mineral wealth in Kenya. Indeed, this writer found it curious during the tour to Biliqo-Bulesa Conservancy in February that the Chinese were already mining mica and other minerals in Nyachis and Sabarwawa areas, which are located in an inaccessible part of Biliqo-Bulesa Conservancy. This writer has since learned that the Chinese have stopped their operations there following the raging controversy over NRT operations in the Conservancy. However, what this writer was unable to establish was the connection between the NRT and Chinese miners and how the latter were allowed to mine in a Conservancy started for the sole aim of wildlife conservation.

Initial symptoms

What is unmistakable though is that Isiolo, a resource-rich county, is already experiencing the initial symptoms of a “resource curse” that is so prevalent across Africa and which is more pronounced in places that are rich in minerals. Usually, the curse unfolds whenever governments unwittingly or deliberately fail to pacify areas referred to as the “backwaters of development”. To cover the void, the communities decide, or are encouraged, to arm themselves to protect their lives and livelihoods from neighbouring communities with whom they share water, pastures and other resources. Soon, bilateral and multilateral agencies, as well as NGOs, find these places attractive for their activities, which are largely passed on as being beneficial to the neglected communities. The agencies are given a near-free hand to operate there since their activities and their effects on the relevant communities are rarely audited by the national governments or independent auditors.

As far as the north of Kenya is concerned, there have been claims that outsiders are involved in supplying arms to the warring communities. For instance, the Small Arms Survey of 2012 says that the British Army Training Unit in Kenya (Batuk) is one of the outfits that have been supplying arms to pastoralists in the north. This has raised the firepower wielded illegally by members of different communities in the north and has led to the transformation of the traditional cattle-rustling activities into intermittent clashes which, if unchecked, can spiral into dangerous, full blown conflicts that might go on for decades.

Because many of the people who run African governments are beholden to vested interests in rich industrial countries, they do very little or nothing to fully integrate the neglected areas into mainstream society. This gives the vested interests ample opportunities to keep the conflicts alive; they result in the same divide-and-rule tactics perfected by Europeans who have kept much of Africa on a leash. In Isiolo for instance, the NRT has encouraged the expansionist tendencies by members of the Garri community, who are said to have migrated from Moyale in Ethiopia following the change of government in Addis Ababa that occurred a few year ago. Encouraged by NRT, the Garri now constitute seven out of the eleven board members of Gotu-Nakurpat Conservancy that neighbours Biliqo-Bulesa.

At the same time, there is evidence that NRT has been facilitating inter-community and intra-community tension and conflict in the conservancies in Isiolo. We learned that for years, the Borana community, whose most members are opposed to ongoing NRT operations in Isiolo, had almost lost their ability to fight for human and land rights. According to a local elder, Mzee Mohamed Adan, this was after the organisation influenced the withdrawal of guns held by homeguards who earlier defended the Borana. He added that since the Conservancy was formed, the community has experienced nine raids conducted by Samburu morans, during which over 70 people were killed and thousands of livestock stolen. From interviews with past officials of the conservancy board and other community members, it emerged that 59 of the people were killed by Samburu morans who were assisted by the specially-trained NRT rangers who travelled there in NRT-branded vehicles. The rest of the victims died after young men from the Borana community engaged in counter-attacks. The raids, we learned, were well coordinated. The NRT had taken sides and appeared keen to “punish” the Borana for opposing its operations in Isiolo.

Campaign to involve communities

NRT’s operation across Kenya was informed by the campaign for the involvement of communities, and especially those inhabiting wildlife dispersal areas, in the national conservation programme. This began in early 2000s and particularly after the IUCN’s World Parks Congress held in Durban, South Africa in 2003. The campaign was inspired by the need to preserve ecosystems and wildlife habitats that happen to be on lands owned and held by local communities. The effort was entrenched in law following the review and enactment of the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act in 2013. Championing the model have been conservationists who claim that 70 per cent of Kenya’s wildlife is found outside national parks and reserves and that the survival of protected areas largely depends on the preservation of vast habitats and lands used by wildlife away from parks.

NRT was founded by Ian Craig in 2004. Craig is a holder of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), awarded in 2016 by Queen Elizabeth II for “services to conservation and security to communities in Kenya”. Craig’s family owns the 62,000-acre Lewa Conservancy in Laikipia, which is said to have been given to his great-grandmother by the British government in 1918 for serving during the First World War. Craig, who was raised in Kenya, is the father of Jessica Craig, the young woman who was once believed to be romantically involved with Prince William.

Since its formation, the NRT has been receiving billions of shillings in grants from a number of European countries and the United States as well as international NGOs, such as the Nature Conservancy (TNC), private trusts and rich people in the West. As a result, the NRT has managed to set up 35 conservancies across northern and coastal regions that now cover a whopping 44,000 square kilometers or over 10 million hectares (i.e. about 8 per cent of the total land surface in Kenya). These conservancies are mainly in remote places where the Kenyan government has little or no footprint. The NRT has been trying to fill the void by altering and adding to its initial conservation mandate a number of activities, including security, prevention of cattle rustling, running a credit scheme, meeting the needs of the communities and livestock marketing.

It is out of this hue and cry that this writer accompanied the team that carried out the fact-finding mission in Biliqo-Buulessa Community Conservancy. Included in the team were representatives of the Isiolo-based Waso Professional Forum, the Borana Council of Elders, the Sisi kwa Sisi organisation formed by students from the School of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure at Kenyatta University, journalists as well as representatives from the Errant Native Movement.

True state of affairs

Kimathi, who is also a member of the Errant Native Movement, says that it was important to establish whether the allegations made against NRT were true. He told this writer that his team bore in mind the fact that livestock production remains the most important livelihood activity for the community and that any tourism activity or other economic undertaking can only supplement, but not replace, livestock husbandry. He added that the joint team experienced firsthand how NRT had been violating the rights of the community.

“We visited the Biliqo-Conservancy between January 26 and 29, 2019. Prior to the tour, we were informed that NRT had, on ten different occasions, used its influence within the security and administration establishments in Isiolo County, and especially in the Merti Sub-county, to frustrate the desire by the community to hold a meeting to deliberate on whether or not to continue with the conservancy. Indeed, we found out that conducting the fact-finding mission was risky,” says Kimathi.

According to community members interviewed by this writer, the NRT had earlier sent its officials who would travel in the organisation’s vehicles “inciting and buying off” some communities in order to unleash chaos during the planned community meeting. To avoid what would have otherwise become an ugly encounter, Kimathi’s team decided to hold long discussions with members of the community on the evening of January 26th at Biliqo Market, during which different people there narrated how the conservancy was started and the harrowing experiences they have experienced at the hands of NRT rangers and Samburu raiders. They also claimed that the NRT has introduced lions into the conservancy, which have been killing livestock and attacking and injuring some of the residents.

“On the morning of January 27th, we visited and interviewed some of the family members of the victims killed during the Samburu raids and counter-raids by the Borana,” said Ms Munyinyi. The consultant on indigenous land rights added that many of the interviews were held in their homes at the Buulessa Market. “As this was going on, we saw rowdy young people being ferried to the venue of the meeting by Land Cruisers belonging to the NRT and the Biliqo-Buulessa Conservancy who shouted threats to members of the team, saying they would kick them out of the area. Later, the rowdy youth succeeded in disrupting the meeting.”

On their part, the police from the Merti Police station, who were present, appeared more interested in finding out whether the conveners of the meeting had a permit. They were unwilling to stop the rowdy youth from disrupting the meeting even after finding out that the conveners had indeed taken the necessary steps, as is required by the law. Eventually, the police stopped the meeting and ordered everyone to disperse, which greatly pleased the rowdy youth.

It was apparent that the Acting Deputy County Commissioner (DCC), James Miring’u, and the Assistant County Commissioner (ACC), Njeru Ngochi, were of not much help either. The DCC and the ACC were evidently not in control. When interviewed by this writer, they expressed ignorance of the connection between insecurity and NRT operations in the Conservancy. However, it was not clear how the sub-county administration would have failed to notice (or investigate) the alleged killing of tens of people and the invasion of Borana people’s land by the raiders.

Traditional conflict resolution mechanisms

According to Dr. Abdullahi Shongolo, a consultant with the Germany-based Max Planck Institute of Social Anthropology, the Borana, Samburu, Somali, Rendille and other pastoralist communities in the north avoided conflicts by sending elders to seek and negotiate for permission to graze in each other’s lands, especially during droughts.

The intermittent conflict in the Conservancy is not new; inter-community conflicts in the north have a long history. The conflicts usually start off as “normal” cattle raids or as competition over water and pasture. But they have worsened with the proliferation of small arms in the region. In the past, local communities had established effective traditional mechanisms to either avoid the conflicts or to resolve them whenever they occurred.

According to Dr. Abdullahi Shongolo, a consultant with the Germany-based Max Planck Institute of Social Anthropology, the Borana, Samburu, Somali, Rendille and other pastoralist communities in the north avoided conflicts by sending elders to seek and negotiate for permission to graze in each other’s lands, especially during droughts. Usually, the elders from the affected community would visit their counterparts in communities that were not as affected by the droughts with a message of goodwill and to seek grazing permission on behalf of their community members. In most cases, such a request was granted once the elders in the relevant community assessed the available pastures and deliberated on where to allow the affected people to graze their animals. But, according to Dr Shongolo, this system was done away with following the appointment of chiefs and elected leaders who can now make unilateral decisions on this matter without consulting the community, especially after money has changed hands.

This has been complicated further by the entry of NRT, which has altered the power and traditional governance structures of the communities in the north and replaced traditional natural resource management systems, such as the Dedha system practiced by the Borana, with “modern” systems. Instead of working through institutions such as the Dedha Council, NRT has appointed conservancy managers, security scouts and members of the conservancy boards who have effectively taken over the decision-making roles that were the preserve of the elders. These NRT-appointed managers and boards now wield largely unchecked and ultimate power in the conservancies. NRT has also imposed its influence on the management of resources by reducing the grazing area of the Borana community in the Biliqo-Conservancy.

“After we came back from Biliqo-Bulesa, it was clear that NRT has capitalised on the lack of awareness of the land rights of the inhabitants of the Conservancy to violate their rights,” said Ms Munyinyi. She added that it is also clear that security issues in the Conservancy, as well as in other parts of in the north, are made worse by the fact that the Kenyan government has largely ceded its responsibility of providing security to the residents. “There is evidently a thin line between the roles of conservancy security teams formed by the NRT vis-à-vis state security personnel because the former are well-trained and equipped with sophisticated weapons and have been handling roles that are legally the preserve of the police, the KWS [Kenya Wildlife Service] and the county administration.”

In most other countries, no NGO, such as the NRT, would be allowed to conduct security operations that lead to violence and are coercive in nature. In this regard, the Government of Kenya has failed the community of Biliqo-Buulessa and needs to take its responsibilities seriously.