What was South Korea in the late 1970s? Say around 1979, during the first year of Daniel arap Moi’s presidency? It was a military state, run by a soon-to-be-assassinated autocratic leader, General Park Chung-hee, and still eight years away from becoming a presidential republic. It was a state in flux: the killing of Gen Chung-hee left a power vacuum, with political factions vying for superiority amongst the ruins of his toppled dictatorship. By any stretch of the word, South Korea entering the 1980s, and for much of that decade, could be described as a nation in turmoil, politically, economically and developmentally. It was a state at risk of falling back into chaos and becoming a cautionary tale.

Kenya, on the other hand, had new leadership. At the beginning of the 1980s, it was viewed by the international community as a shining example of a post-independence African state that looked set to be an economic powerhouse of the future. At that time, Nigeria was still under a military junta and South Africa was regressing into the bloodiest period of anti-apartheid action.

Yet, by the tail end of the decade, Seoul was hosting the 1988 Olympics, and less than four decades on, in 2016, South Korea had the 11th highest GDP on earth, behind Canada and ahead of Australia. According to the United Nations, in the same year Kenya was ranked 75th, just behind Uzbekistan and ahead of Guatemala.

What happened? A major factor is South Korea’s investment in the creative economy versus the Kenyan government’s approach of letting the entire sector be deprioritised and left to flounder alone.

In the case of South Korea’s film industry, one major shift occurred in 1994. At the time Hollywood films controlled most of the market while locally produced films controlled less than one-fifth. The government took a decision to invest in and emphasise locally-made films. Since then, the South Korean film industry, when coupled with K-Pop, has seen the rise of the “Korean wave”, a globally influential and massively profitable enterprise. It remains the modern model of the need for government support for the local creative industries.

With regards to K-pop (the Korean brand of bubble gum-style pop songs), the Government of South Korea played a direct hand in sustaining the momentum of this global musical force. A Ministry of Culture was formed in 1998, including a specified department exclusively overseeing the development of the nation’s music, with millions of dollars pouring in. Where the difference is further highlighted was the government’s targeting of music as a potential cash cow for the languishing economy. Much of Asia had been sucked into a whirlwind of economic turmoil in the late 90s, and the government needed alternatives for employment, taxable revenue and global influence. The government also ensured protection through effective policies and engaging with music industry members. Fast-forward two decades, and K-Pop is a US$ 5 billion industry.

In the case of South Korea’s film industry, one major shift occurred in 1994. At the time Hollywood films controlled most of the market while locally produced films controlled less than one-fifth. The government took a decision to invest in and emphasise locally-made films. Since then, the South Korean film industry, when coupled with K-Pop, has seen the rise of the “Korean wave”, a globally influential and massively profitable enterprise.

The creative economy has been defined as the ultimate economic resource within a nation. It’s the umbrella under which art, architecture, film, television, music, poetry, sculpture and writing exist. Kenya’s creative sector is a vibrant one, brimming with talent and possibility, especially when looked at through the opportunities it affords to the youth of the country.

Such opportunities are not exclusive to the Kenyan economy as the world is becoming modernised, and the creative sector is often an accompanying industry to modernity. In fact, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has stated that the economic potential of the global creative sector was worth more than US$ 2.2 trillion in 2015. The creative industry has undeniably massive impact upon a nation’s potential GDP and can offer a built-in solution to lingering questions of “development”. A 2013 report from UNESCO outlines that the cultural sector is a vital aspect of the sustainable development of a nation, as the creative sector is not only one of the fastest growing sectors in the world, but also can be highly transformative in terms of income generation, job creation and a nation’s earnings through export. A 2010 policy statement released by the United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) further reflects this, stating that culture is the fourth pillar of sustainable development for any nation.

So with all of this potential, why does the creative sector in Kenya languish? Why has Kenya not taken the leap into the void of the sector, that same leap that has produced billions for other nations, including within Africa?

The state of Kenya’s creative industry

An all too common complaint among artists within Kenya is that the creative industry is simply not a “serious” entity to be pursued as a path to a successful and lucrative career. This “lack of seriousness” has resulted in one of the worst policy frameworks for the arts in the developing world. Concerts go unattended, books are not bought (if they can be published at all), grants are not delivered, artistic facilities remain unfinished and draconian regulations are imposed on the content that can be produced. Radio stations play music from abroad and theatres show foreign films. As Nairobi-based singer-songwriter, Tetu Shani says of the current situation, “The day that Kenyan artists start living like politicians is the day you’ll see a shift in public perception and consumption.”

This issue is exemplified by the lack of policy and effective implementation of regulations surrounding the creative industry. When examining the music industry, the crux of the issue comes down to copyright. Most casual fans of Kenyan music are familiar with the story of the band Elani, which had a smash album and multiple hits in 2013 and 2014 after the release of their record Barua ya Dunia. The airplay was steady and the singles very successful. In 2016, Elani criticised the Music Copyright Society of Kenya (MCSK), stating that the organisation had only paid them royalties totaling Sh31,000. MCSK has been embroiled in constant legal and legislative turmoils, and had its capacity to collect, track and distribute royalties to Kenyan artists revoked due to a court order in 2018. MCSK has since been replaced by the Music Publishers Association of Kenya (MPAKE) in the role, yet the headlines and legal issues remain.

The ones who seem to get lost in the shuffle are the artists. The example of Elani is at the core of the problems that face the creative industries in Kenya; while there might be growth of the sector on paper, the artists or creators themselves don’t see the benefits materialising within their wallets. At an even more micro level, take the example of the National Environment Management Authority of Kenya (NEMA) enforcing noise pollution regulations against DJs in Kenya; security forces routinely go into clubs, arrest DJs for exceeding “noise restrictions”, even as they spin on the decks, and haul them off to jail. Such enforcements were not communicated effectively to the members of the music industry.

Again, the issues surrounding the enforcement of regulations continue when examining the burgeoning film industry in Kenya. Some estimates contend that over 90 per cent of films in Kenya are pirated, with the heavy-handed punishments outlined by legislation being rarely enforced.

On top of this, the head of the Kenya Film Classification Board (KFCB), Dr. Ezekiel Mutua, has made free expression through film and television markedly more difficult. Beyond his public criticisms of “gay lions” and cutting the release timeframe of Rafiki, the highest profile Kenyan film since 2011’s Nairobi Half-Life, down to less than a week (just enough time to qualify for the Academy Awards), Dr. Mutua has enacted steep license fees that have reduced the industry’s ability to operate independently, including the hoop-like requirement of filmmakers needing multiple licenses to film in multiple counties. It has become common for Kenya-based films and content to be filmed in South Africa. Indeed, Mutua’s attempts to enforce his dictates on theatre as well as the film industry have led content creators to further eschew any connection with the government.

On top of this, the head of the Kenya Film Classification Board (KFCB), Dr. Ezekiel Mutua, has made free expression through film and television markedly more difficult. Beyond his public criticisms of “gay lions” and cutting the release timeframe of Rafiki, the highest profile Kenyan film since 2011’s Nairobi Half-Life, down to less than a week…Dr. Mutua has enacted steep license fees that have reduced the industry’s ability to operate independently, including the hoop-like requirement of filmmakers needing multiple licenses to film in multiple counties.

Kenya had a booming fashion industry in the 1980s, which contributed 30 per cent to the manufacturing sector. Since the 1980s, the continual influx of mitumba (second-hand clothes) has cut this employment severely. The change was brought about by the government cutting regulations and import tariffs in the late 1980s, cutting down on the cotton and garment sectors. This led to an increase in the jua kali nature of the sector, with members of the garment industry having to find their own work after the majority of the cotton production mills shut down. In turn, this contributed to much of the textile industry being a separate entity from that of the clothing production industry – an issue exacerbated by the lack of a unified industry body to advocate for the fashion sector.

This last point regarding the fashion industry of Kenya is truly a key issue that swirls around the creative sector in Kenya. Much of the industry remains fragmented, splintered and run by independent individuals and micro-organisations operating unofficially outside of government taxation or influence. The lack of a structured unified body is reflected in other creative industries, which lessens the sector’s ability to engage in any sort of meaningful dialogue with the government. These issues of associational divide were echoed by HIVOS in 2016, which stated that “the current state of associations in East Africa is that they are fragmented, disunited and lack a consistent agenda on how to engage the government and different industries to ensure the standards of the industry consistently improve”.

So what does all of this amount to? There is one commonality: the utter lack of possible taxable revenue as a result of obtuse and inadequate policy. According to PricewaterhouseCoopers, the entertainment industries are growing across the board; revenues are up, as is Internet access and the number of viewers within the Kenyan market. However, Kenya is trailing far behind other nations that have capitalised on the bolstering of income from the creative sector.

Kenya vs other major African markets

The stagnant creative sector in Kenyan becomes apparent when examining the state of other African creative sectors. When looking through the lens of the two other leading sub-Saharan African markets (Nigeria and South Africa) the differences and gaps becomes stark.

Both South Africa and Nigeria have music industry infrastructure that focuses on the regulations of the industy. This includes promoting local artists while protecting their ability to garner revenue from their work and punishing those who take advantage. Within Nigeria, artists are promoted, DJs play the latest local tracks and help to encourage grassroots growth of new musical artists.

The most glaring example of a creative economy’s potential is the constant streaming of Nollywood movies on Kenyan televisions. How exactly did the Nigerian film industry become so massive in recent decades, dominating the African market and influencing global media beyond the continent? It is a remarkable story of growth, with Nollywood’s early roots tracing back to the colonial era of the early 20th century.

The independence of Nigeria from British rule in 1960 resulted in further expansion of the film industry. The key moment came in 1972, when the Indigenization Decree was issued by Yakubu Gowon, the Head of the Federal Military Government. The original intent of the decree was to reduce foreign influence and pour wealth back into the hands of Nigerian citizens. The international business community publicly complained, threatened to pull out, and in some cases reduced their investment. The Indigenization Decree led to hundreds of theatres having ownership transferred from foreign hands to Nigerian ownership.

In the years that followed, widespread graft was discovered in multiple industries (much due to foreigners paying for corporate “fronts” while secretly maintaining control). Gowon was deposed while abroad in 1975 and the film industry continued to grow. New theatre owners started to show more and more local productions, with the result being Nollywood experiencing a further expansion across the next decade as Nigerian citizens were suddenly directly involved in not only the control of the theatres, but also in what Nigerian audiences were more likely to buy a ticket to see, buy a VHS of, and later buy a DVD or stream: local content. Out of the ashes of colonialism, a bloody civil war and a military junta rule, Nollywood grew organically, hand over fist, year after year.

By the mid-1980s, Nigeria was producing massively profitable blockbusters and revenues grew to over US$11 billion (Sh1.1 trillion) by 2013. The industry also employs an eye-popping one million people, estimated to be second only to agriculture in terms of number of employees within Nigeria.

In the 21st century, the Government of Nigeria has taken further notice, mostly through the recognition of the massive benefits to the nation that the local film industry provides. Currently the government is working in conjunction with the National Television Authority of Nigeria to expand the industry, offering grants, expanding infrastructure and constructing a production facility. Perhaps most notable was the 2010 signing by former President Goodluck Jonathan of a US$200 million “Creative and Entertainment Industry Intervention Fund” in order to encourage the growth of Nollywood and other creative industries. Put another way, Kenya’s GDP is approximately one-fifth that of Nigeria’s, but there has been no US$40 million fund signed by the government towards the nation’s creative sector.

By the mid-1980s, Nigeria was producing massively profitable blockbusters and revenues grew to over US$11 billion (Sh1.1 trillion) by 2013. The industry also employs an eye-popping one million people, estimated to be second only to agriculture in terms of number of employees within Nigeria.

This is the point where naysayers to the potential of the creative economy will argue that corruption is endemic in Kenya, and therefore, reaching the heights of Nollywood is inherently impossible. This is a fallacy: Transparency International in 2017 ranked Kenya 143 out of 180 in terms of corruption and Nigeria came in at 148. Despite obvious governmental and corruption shortcomings in Nigeria, when it comes to the film industry, one thing has certainly been recognised: that money talks.

South Africa took a different route towards becoming a creative sector powerhouse on an international scale. This is best exemplified when examining the music industry of the country. Once again, the roots of the explosion of South African musical influence can be traced back to a government development programme – the Bantu Radio initiative, which, it must be stated, was put into place in 1960 by the apartheid government in what can best be described as a campaign to further segregate the country. The aim of the programme was to promote tribal music in the hopes that it would reinforce pre-colonial cultural barriers between different communities. It also had the not-so-subtle goal of establishing what black South Africans enjoyed in order to aid the apartheid government in further profiting off of them. The regime believed that the radio stations would play exclusively folk music, but the result was somewhat different. Bantu Radio began broadcasting more than a dozen different genres of music, among them Afro-jazz, kwela and isicathamiya. These genres exploded in popularity, bringing fame, recognition and influence to many South African music industry figures.

The South African Broadcasting Corporation was soon brought in to monitor and regulate the music being produced to ensure that the messages of the music didn’t criticise the apartheid regime or its policies of systemic racism. Further regulatory bodies were established to control the music being played. They did so effectively on the Bantu Radio network, but had also inadvertently “let the cat out of the bag”. There had been a long history of rebellious action through music in South Africa, but now there was an audience of millions who had several genres in mind on what to pursue. Popular artists who were censored on the radio took their messages directly to their audiences. There was an exodus of musicians who left South Africa in order to make music against the apartheid regime without censorship or reprisal. In 1982, the Botswana Festival of Culture and Resistance was held with much of the attendance made up of South African exiled musicians. At the conference, it was decided that the primary weapon of the struggle against apartheid would be culture.

Accidentally, through an attempt to further exploit and divide, the regime had laid the groundwork for both widely popular musical genres with a captive local audience. By 1994, when the last remnants of apartheid were finally thrown aside, the music industry grew massively and continues to be a dominant presence into the 21st century.

Anti-apartheid films, rising from South African independent cinema experiencing a boom in the early-80s – the same period when there was a proliferation of video cassette recorders – allowed the viewing of “subversive” productions. Some of these same anti-apartheid films (banned by the regime), such as 1984’s Place for Weeping, gained international traction and helped to establish South Africa’s film industries as influential outside of the borders of the apartheid regime.

What the creative industry has done for other nations

A UNESCO convention in 2005 stated that there is still a need for governmental frameworks that focus on “emphasizing the need to incorporate culture as a strategic element in national and international development policies, as well as in international development cooperation”. By this standard, the example of South Korea once again stands out. Just how did South Korea springboard its culture into a massive entertainment and creative sector in such a short period of time? The answer is fairly straightforward: the progress of South Korea’s entertainment sectors centres around heavy governmental support, funding and infrastructural management. The government designed and implemented a multi-stage plan towards increasing the profile, impact and economic viability of its entertainment industries.

With the example set, it becomes all the more glaring that the Government of Kenya has turned its back on its own creative industry. The Korean problem of foreign influence is a Kenyan one; foreign acts are flown in and given top billing, foreign media houses dominate the telling of Kenyan stories, and the latest Marvel films always find themselves on movie-house posters. Ask yourself, when is the last time you saw a Kenyan-made film on an IMAX screen playing to a packed audience? The lines are there, but who are there to see?

The state of regulation and progress within the creative sector in Kenya reflects an acute failure of the state to implement the very policies it has outlined. One needs to look no further than the Kenyan Constitution of 2010 and the Vision 2030 Development Goals to find evidence of this.

With the example set, it becomes all the more glaring that the Government of Kenya has turned its back on its own creative industry. The Korean problem of foreign influence is a Kenyan one; foreign acts are flown in and given top billing, foreign media houses dominate the telling of Kenyan stories, and the latest Marvel films always find themselves on movie-house posters.

In Kenya, a nation that jailed poets and playwrights only two decades ago, the promotion of the creative arts is evolving too slowly. While the Constitution included the mandatory promotion of the arts and cultural sectors, it has taken close to a decade to pass legislation regarding these industries. The government itself has acknowledged these disconnects: the National Music Policy of 2015 states that the Government of Kenya has not adequately enacted policy relating to the creative sector, which in turn has promoted a disconnect in communication and stymied the potential for growth within the industry.

Addressing the state of the creative industries in Kenya, UNESCO contends that there is no facilitative policy framework regarding the creative sector. Or, more bluntly: talk is cheap. The Government of Kenya is definitely aware of the potential impact of growing these specialised industries; it just avoids enacting any meaningful regulation surrounding them. Take the film industry for example. While the talk has been big, there has been no sign of the promised public investment.

The creative sector has long been associated been with the employment of youth. The United Nations has released a series of reports contending that a key path towards combating youth unemployment is through the promotion of the creative industries. Unfortunately, it seems that the Government of Kenya is yet to take heed of creative-driven solutions. The country is currently mired with massive youth unemployment, with rates of over 20 per cent, dwarfing the levels of unemployed young people elsewhere in the East African region. It is clear that from an economic standpoint, the policies of industrialisation have long since proven themselves to be insufficient in terms of impacting the youth of Kenya in any sort of meaningful way.

One reason why the government is reluctant to promote the arts is because of its delicate sensibilities: it fears supporting creative minds that may turn out to be critical of it. This is evident across the archaic policies of the KFCB, the exodus of locally produced textiles for fashion, the lack of funding for the National Theatre, the government stake in Safaricom, which is currently facing a backlash for the low rates of compensation given to musicians streamed on its ring-back tunes application, Skiza.

On the basis of the examples given, the lessons to be learned from South Africa can only be to lean harder into criticism of the government. While this seems to be an oft-visited theme throughout the creative sectors in Kenya, the apartheid era of South Africa’s music industry remains a solid reminder: that there’s no point backing off if the government refuses to change.

This rings doubly true in cases such as that of Ezekiel Mutua, who seems hell-bent on smothering the Kenyan film, theatre and television industries to death through self-claimed piety. His crusade against homosexuality and what he describes as “immorality” must be viewed as a neocolonial one; its aim is to kill off grassroots Kenyan enterprising creative expression. The efforts against him should focus on his willful draining of the Kenyan economy’s untold economic and cultural potential.

The best long-term solution in Kenya’s case is a sort of middle-ground between the policies of localised emphasis of the 1970s and the government of South Korea in the 1980s and 1990s. Ideally, the Ministry of Sports, Culture and the Arts would be divided towards being specialized; the government would either put in or find real public and private funding for the arts and then actually implement and regulate the policies, such as the National Music Policy of 2015, which outlines a mandated quota for Kenyan-made content to make up 60 per cent of the music aired by the media within the country. They would enforce the regulations but let artists do their own thing as a private enterprise, as they know the ins and outs of the industry. When grievances arise, representatives from the creative sector would have a meaningful seat at the table to dialogue with the government. Unfortunately, none of these solutions are being sought.

This rings doubly true in cases such as that of Ezekiel Mutua, who seems hell-bent on smothering the Kenyan film, theatre and television industries to death through self-claimed piety. His crusade against homosexuality and what he describes as “immorality” must be viewed as a neocolonial one; its aim is to kill off grassroots Kenyan enterprising creative expression. The efforts against him should focus on his willful draining of the Kenyan economy’s untold economic and cultural potential.

The issue remains that while Kenya’s creative industry is at par with nearly any other in the region, the continent or the developing world in terms of potential, it is being systemically held back from reaching the heights of its peers. Both South Africa and Nigeria’s situations can be viewed as the regimes having stumbled into a goldmine of creative industry potential during brutal regimes, but in both cases there was at least an initial search for the vein (racist though South Africa’s was). In the case of South Korea, there was almost a resolute desperation to never return from whence they came. They were willing to try outside-the-box solutions to get there and to put their money where their mouth was. All three situations in 1979 stood on a precipice, and all three could have easily changed course into further crackdown or lack of interest and being left devoid of a cultural sector. Kenya’s creative sector situation is dire. This constraining of creativity must be viewed in the light that it is impeding Kenya’s progress in the opening decades of the new millennium.

The artistic industries in Kenya are currently at a crossroads. Though ideas, products and creativity coming from the country are only growing in terms of influence and quality, without support, all potential is destined to languish in obscurity. Seventeen years since the transition out of the Moi regime, there has been no golden age of the arts, no explosion of international influence and possibility. The talent is there; the infrastructure of community radio, self-starter production houses and subversive literary talent is pervasive in Kenya. However, the government is simply too afraid or too obtuse to put anything behind these efforts.

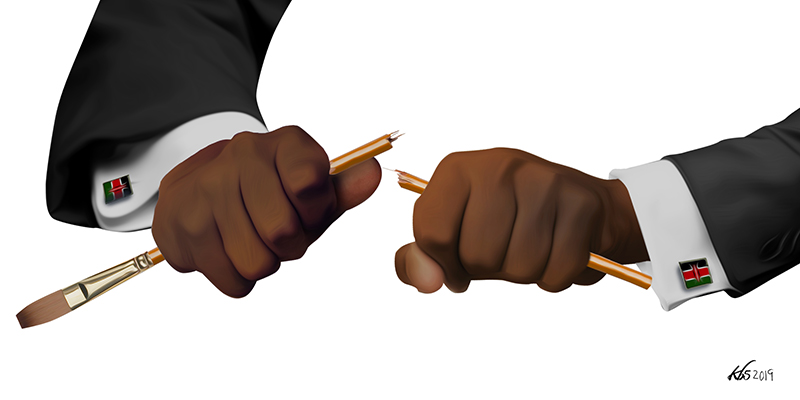

What will the economy of Kenya 40 years on into the future look like? As things stand, without the government at least trying something different, South Africa, Nigeria and South Korea will continue to lap Kenya, toasting to their home-grown billions of dollars and expanded economic influence. Will Kenya’s government officials continue to pretend to scratch their heads in search of “new solutions” when the answer is literally painting the picture before them?