“National liberation, the struggle against colonialism, the construction of peace, progress and independence are hollow words devoid of any significance unless they can be translated into a real improvement of living conditions.”

~ Amilcar Cabral, African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde

Given the disparity between Uganda’s economic growth and the increasingly precarious existence of most of her citizens, Ugandan economists need to devise a measure of economic growth that reflects the needs and aspirations of the indigenous population.

Economic growth, as measured by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Uganda, is not synonymous with access to life-supporting conditions. GDP is primarily used as an indicator for aid decision-making by investors. Investors – whether charter companies, venture capital funds or multinational companies – have served to create employment and to raise living standards in their countries of domicile. Debt is the means by which net outflows of wealth from developing countries is achieved.

Human development indicators stand outside GDP and may or may not be considered (and are usually not considered) in the measurement of progress. What is required is an indicator of economic growth that is linked to the health, well-being, education and general prosperity of Ugandans. To have any real use, the measure would also have to factor in the impact public debt repayments have on household access to basic requirements, such as water, food and useful education.

Insisting, as the government and international lending agencies do now, that debt repayments are sustainable as long as they remain under 50% of GDP masks the fact that even with that debt-to-GDP ratio, the prevalence of undernourishment in Uganda remains high and access to improved water and sanitation remains low. Uganda’s debt repayments stand at 38% of GDP and between 26% and 36% of the population is undernourished. Now that public debt has risen to 50% of GDP, it is misleading to paint a rosy picture of the economy.

The IMF’s World Economic Outlook of April 2018 reported Uganda’s annual economic growth rate to be 5.2%, compared to 5.5% for Kenya, 6.4% for Tanzania and 7.2% for Rwanda. The East African Community’s other members, Burundi and South Sudan, were reported to have low or negative economic growth rates (0.1% for Burundi and a negative rate of -3.8% for South Sudan), the result no doubt of the ongoing internal conflicts in these countries.

Insisting, as the government and international lending agencies do now, that debt repayments are sustainable as long as they remain under 50% of GDP masks the fact that even with that debt-to-GDP ratio, the prevalence of undernourishment in Uganda remains high and access to improved water and sanitation remains low.

However, growth statistics reported for Uganda and the East Africa region may really be a reflection of the activities of and benefits enjoyed by multinational corporations, other investors and political elites and could have little relation to the average Ugandan or East African. An East African or Ugandan Economic Statistics Review Group could usefully be set up to find more meaningful measures, including non-monetary factors, that would reflect the improvement, deterioration or stagnation of the standard of living. It is a major in-built weakness in governance to rely on external entities (whose priorities are not necessarily our priorities) to manage and report on the economy.

Against the background of inadequate human development, Roger Nord, the deputy head of the IMF, approved the findings of Uganda’s Debt Sustainability Analysis of December 2016. As is now known, that report stated erroneously that Uganda was at low risk of debt distress and that there was no risk of domestic debt undermining the country’s ability to meet debt repayments.

Adam Mugume, the executive director for research at the Bank of Uganda, thought differently. He warned that falling commodity prices and the sliding value of the shilling had the potential to worsen an already precarious debt position. More recently, the Central Bank has warned that sovereign default remains a real danger. The Auditor General weighed in with a warning that interest payments on domestic debt are pushing the country towards debt distress. However, the IMF’s opinion prevailed for reasons that go back to the 1884-1885 Berlin ‘Scramble for Africa’ Conference and all that came after it.

The IMF followed up its misleading assurances in April 2017 when Mr Nord said on KTN that although the economic outlook for Africa was generally subdued, the one bright spot was East Africa where regional integration was progressing. He cited the flow of goods, services and people without indicating how IMF policies have impacted those flows since 1986/7 when the structural adjustment programme (SAP) began. Integration in to one economic bloc, Nord said, would make East Africa an even more attractive destination for foreign investment in much needed but expensive infrastructural development – a message of encouragement to investors that took no account of human development.

Federation has clear advantages connected to economies of scale in developing infrastructure. What is argued here is that integration could also consolidate corruption and the accompanying means of repression. Loans already spent have not always yielded value for money, a fact the IMF does not acknowledge. As it is, there is a need to be hypervigilant at the national level in monitoring debt and the terms and conditions under which it is incurred. Uganda would have done better to strengthen her own governance before embarking on ever closer union with other countries.

Foreign direct investment is often financed by credit made available to investors under government schemes in their own countries for projects that they propose to the target countries. Recently, the UK launched the Export Finance (UKEF) line of credit under which the government of Uganda borrowed €270 million to build an airport. The condition is that British companies are to be used to do the work.

Federation has clear advantages connected to economies of scale in developing infrastructure. What is argued here is that integration could also consolidate corruption and the accompanying means of repression. Loans already spent have not always yielded value for money, a fact the IMF does not acknowledge.

Britain now produces 60% of her food requirements and imports 30% of the rest from the European Union. Her emergency reserve is good for five days. Britain has a perpetual balance of payments deficit which will only be made worse after Brexit when imports from the EU will become more costly. It made sense therefore to offer British companies credit and so far, in addition to an airport, from which GBP100 million worth of exports to Uganda is expected to result, the UK won contracts in Uganda worth over US$2 billion in 2017 alone.

Whether Ugandan leaders looked beyond the easy availability of the credit and considered with enough rigour the prioritisation of an airport, the strength of the technical proposals or the relative cost remain to be seen. What is almost certain is that no effort was made to ensure that Ugandan businesses and professionals participated in those development projects and that there was a transference of skills.

The history and purpose of federation

Britain’s reasonable interest is to maintain employment to enable her workers to purchase food. One MP summed up the situation up as: “We have to buy our food from outside, and in order to buy our food we have to exchange manufactured articles, but before we can exchange manufactured articles we have also to buy from outside the raw materials from which to manufacture them.”

East African federation has always been seen as a solution to Britain’s economic challenges. During the slump of the 1920s, UK’s parliament considered possible solutions. These included encouraging the three million unemployed to migrate to the Dominions and to the colonies and creating more jobs in the textile industry by creating a larger source of cheap cotton to substitute the more costly American variety. This was to be done by investing in a railway and harbour through which to export the cotton from Uganda and Kenya. The beauty of it was that it would be paid for out of cotton taxes and native poll tax paid by the growers.

Federation was first formally considered for East and Central Africa by parliament in 1925. An early triumph or regional cooperation was the co-financing of the Mombasa port and the Uganda Railway. The benefits were not evenly distributed – Kenyan customs collected and retained the duties paid for Uganda’s trade through Mombasa for the first ten years. The Uganda Railway itself began and ended in Kenya from where a steamer completed the journey.

Later there was a movement in colonial Kenya to break away from Britain and form an autonomous state similar to the Union of South Africa. Kenyan settlers who dominated the Legislative Council proposed that Kenya be allowed to spend GBP80,000 (roughly the equivalent to the annual budget of the Colonial Office) to build the East African High Commission as the future administrative building for an expanded Kenya.

The anticipated self-governing federal state was to incorporate Uganda and Tanganyika. There was talk of uniting a future East African Federation with the Central African Union (of Rhodesia and Nyasaland). From Uganda’s point of view, this was undesirable because European settlers in Kenya had already planted the seeds of apartheid-style economic domination; they were exempt from income tax; they had exclusive rights to the cultivation of profitable crops like maize and coffee granted by British government ordinances (thereafter claiming entitlement to privileges because they carried the economy); they were entitled to use forced labour and the pay scales were lower for Africans than for Europeans and Asians. Salaries were usually calculated on the basis of a single man living in a hostel near a mine or a farm. In this way, poverty became entrenched as families left behind on Native Reserves tried to eke out a living on the increasingly over-populated Reserves.

The cost of Kenya’s colonial administration was much higher than anywhere else in the region because, as explained at Whitehall, the administration had to be predominantly European to service the settler community. An example given was that a European suspect could not be expected to submit to arrest by an African policeman, therefore expatriate policemen paid on an expatriate pay scale were needed.

Some high-cost social services for use by the Kenyan settler population were paid for with ‘loans’ from the Ugandan treasury. Examples include Hill School, Eldoret, a boarding school for European pupils from the region and the Mombasa Municipality water supply financed in 1959 by a 15-18 year loan to Kenya of GBP1 million. In Uganda there were already segregated educational, medical and recreational facilities for Europeans, Indians and Goans.

To attract more settlers to Kenya, especially from among the unemployed, the Imperial government offered them an existence in which their interests took precedence over those of the indigenous population. Collateral damage to Africans included involuntary population transfers as commercial farms were established, compulsory labour, child labour, flogging, exploitation of women and abandonment of their children and venereal disease.

In 1932 the parliamentary Joint Select Committee on Closer Union in East Africa was set up to examine the issue. The opposition argued that settlers could not be entrusted with the welfare of the Africans and that Britain should continue to play their self-arrogated role of trustee. As in 1925, the committee recommended that the prevailing model in the region be maintained i.e. that the British government through the Colonial Secretary maintain the authority to intervene directly in the affairs of the East African colonies.

Post-independence African leaders entrusted with the welfare of the indigenous population act as middle-men, receiving support for their elections and monetary benefits in return for serving external economic interests. Investors need only secure physical access to leaders or their relatives before emerging with tax-holidays, waivers of environmental law, hectares of free land and permission to displace any local communities in their way.

How different is the subjugation of the interests of the general population by those pre-independence elites from the current situation in which potential investors are offered incentives that are ruinous to the local economy? The only difference between pre- and post-independence multinational corporations is that instead of dealing with colonial administrators they now deal with African kleptocrats.

The East African Legislative Assembly will be able to approve loans. East African federation makes the region more attractive to investors because larger collateral spanning the entire region can be extracted. Having failed to reign in a national parliament that consistently fails to keep public debt at manageable levels and on reasonable terms, there is little reason to expect the East African Legislative Assembly to act any more prudently.

How different is the subjugation of the interests of the general population by those pre-independence elites from the current situation in which potential investors are offered incentives that are ruinous to the local economy? The only difference between pre- and post-independence multinational corporations is that instead of dealing with colonial administrators they now deal with African kleptocrats.

In pushing for regional integration to boost foreign direct investment without paying at least as much attention to raising living standards, the IMF is carrying on from where the Imperial government left off.

The evidence of deepening regional cooperation cited by Mr Nord was “growth remaining quite high and investment proceeding” and regional integration evidenced in the launch of the single passport for East African citizens. Regarding the criteria countries are required to meet before joining the Union, Mr Nord said, “Debt levels are all within – uh – limits. Fiscal deficits remain still on the high side but in most countries are heading down.” He expects a monetary union by 2024. Meanwhile, Uganda’s fiscal deficit is growing.

What the IMF omits from its glowing investment portfolio for East Africa is the fact that all debts incurred by corrupt leaders are likely to be audited. Wherever it is found that they led to abuse of civil rights or that they yielded insufficient value for money, they are liable to be repudiated. Non-ethical investment no longer makes financial sense.

Mr Nord’s condescendingly vague remarks offer little justification for his optimism. (He is often referred to as the ‘Super Minister of Finance of Uganda’.) Civil unrest is constantly simmering in Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda and Burundi. Sudan reverted to all-out war after a hiatus of only two years. The fact is that post-independence East Africa is being set up for exploitation on a new level by foreign corporations and vampire investors aided and abetted by its leaders.

Civil unrest and state brutality

As in colonial times, the current social unrest is symptomatic of underlying problems, chief among which is the lack of economic advancement of the vast majority of East Africa’s population. Civil unrest and state violence are critical economic indicators. This was understood in the past by some British MPs, two of whom are quoted below:

Why is it that the Colonial Office still permits in new ordinances, restrictions on the civil and industrial rights of the peoples of the Colonial Empire? In Sierra Leone, there has been a new spate of legislation designed to increase the powers of the Government in regard to the literature that may be read, in respect to deportation orders and trade union organisation. Recently, there was a new Sedition Law in Trinidad. If these Colonies have been able to get on for scores of years without this legislation being necessary, what new factors are there in the situation which require that these new ordinances of a repressive and restrictive kind should now be passed? Is it that at last the people are demanding that justice should be done, and therefore, it is necessary to put further checks on their powers of expression?

—Arthur Creech Jones MP, contributing to the Colonial Office debate in the House of Commons on 7 June 1939

I ask any hon. Member opposite if he thinks millions of people engaged under conditions like that, having to work for miserably low wages like that, including sometimes some amount of food, can be expected to be in a state of contentment with affairs as they are? Does any hon. Member opposite blame them if occasionally they are inclined to break the law to try to make things better? If the Colonial Secretary tried to look at those problems in that way, instead of bringing down on these people, with all his might and main, every possible policeman, he would be a success.

–Wilfred Paling, MP during the Affairs in Africa debate, 16 December 1953

Sixty years later, failure to gain access to the most basic requirements of decent living, while others live in fear of losing the access they enjoy, it is no wonder there is disaffection among the population. Where there is disaffection, repression is to be expected because Kenya and Uganda retained repressive colonial laws enacted as a response to agitation for independence.

That the IMF deems this state of affairs ‘progress’ is sad but not surprising. Illicit transfers of wealth on the current scale can only be continued by force. From the point of view of an organisation whose primary aim is to secure the signatures of African leaders on contracts committing the region to debt regardless of its sustainability, East Africa is a success. The five strongmen leaders and President Nkurunziza of Burundi are kept in power by foreign aid, which is used to provide the services for which the government should be responsible.

As in colonial times, the current social unrest is symptomatic of underlying problems, chief among which is the lack of economic advancement of the vast majority of East Africa’s population.

The IMF’s campaign of disinformation provides the façade of ethical investment while foreign corporations siphon out the wealth of the African continent.

Beyond austerity to destitution

The latest available figures show that, on average, one third of the population of East Africa is undernourished. (This figure excludes Burundi and South Sudan for which no figures are available but reliable refugee sources have spoken about feeding stations in the towns in both countries.) Despite having the highest economic growth rate in East Africa, nearly half of Rwanda’s population is undernourished. (Rwanda succeeded Uganda as the exemplar of the rightness of structural adjustment.)

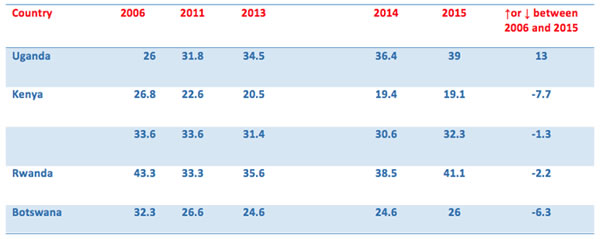

The prevalence of undernourishment in Uganda rose by 13% to the current 39% of the population between 2006 and 2015. In addition, Uganda has pockets of prevalent stunting, a high primary school drop-out rate, and low access to improved sanitation facilities (19% for Uganda, 30% for Kenya, and 15% for Tanzania. These three countries, the original East African Community, have been applying IMF-prescribed economic policies for much longer than Rwanda and Burundi where access to improved water and sanitation stands at 61% and 41%, respectively.)

Prevalence of undernourishment (% of population)

Source: World Bank Health Nutrition and Population Statistics. No undernourishment data on Burundi. Last Updated: 12/18/2017

The prevalence of undernourishment in Uganda rose by 13% to the current 39% of the population between 2006 and 2015. In addition, Uganda has pockets of prevalent stunting, a high primary school drop-out rate, and low access to improved sanitation facilities (19% for Uganda, 30% for Kenya, and 15% for Tanzania.)

Hunger is endemic in parts of the East and Karamoja and the population there is fed and watered by the World Food Programme. Periodic influxes of refugees from South Sudan only serve to exacerbate the problem. At the current growth rate, coupled with the downward spiral in commodity prices and the fall of the shilling to half its 1990s value, it is unlikely that the level of undernourishment or the lack of access to safe water will be significantly reduced.