At a cybercafé somewhere in Nairobi’s South B estate, stone-faced male clients are glued to their computers. They are youthful, the type that ought to be attending college, or if they are working, should be at their respective work places. It is mid-morning on a weekday, the cybercafé’s computers are all occupied and the young men are not on the Internet doing research for a term paper, collecting data, compiling a literature review, or cleaning up their CVs; they are busy placing bets on football games that are being played thousands of kilometres away, mostly in European cities.

This cybercafé is a replica of the many cybercafés spread all over the city and in suburban areas that have been turned into betting sites. “Cybercafés are no longer the Internet places you knew where people came to download serious stuff, upload a government document or even watch porn,” said Moha, the cybercafé’s owner and himself a former betting addict. “With the introduction of online betting in Kenya, the cybercafé business was transformed and acquired a new model.”

In Rongai town in Kajiado County, 25 kilometres from Nairobi’s city centre, college students and young professionals have turned to cybercafés to gamble in the football betting craze that has left many residents befuddled. “All of them are male and between the ages of 19 and 35 years,” said a cybercafé owner. “A young man who was working for an IT company left his job to bet full time.” In Kikuyu town, Kiambu County, many young men have been sucked into the betting craze. They spend all day holed up in cybercafés, betting on nondescript teams in faraway countries, such as Bulgaria and Ukraine. They pay KSh1,000 upfront to cybercafés daily to satiate their betting addiction.

“Betting has become a full-time occupation for some people,” said Njoroge, one of the young men I found betting at Moha’s cybercafé.

A recovering gambler, Moha was so compulsively addicted to betting that he would bet his cybercafé’s daily proceeds relentlessly and non-stop. Convinced that the following day would be better than the previous one, he would place his bet again and again. Again and again, he would lose: day after day, week after week, month after month. “Just when the business was now about to collapse, I woke up to my senses. I was lucky, I salvaged myself. It could have been worse,” said Moha. At the end of his betting mania, Moha had lost hundreds of thousands of shillings. “That money was never meant to be mine,” he consoled himself.

A full-time occupation

Moha’s cybercafé is decked with a smart 43-inch TV that beams the latest European leagues’ football matches live. I watched as young men worked their bets with the seriousness of college students sitting for an exam. “Betting has become a full-time occupation for some people,” said Njoroge, one of the young men I found betting at Moha’s cybercafé.

Njoroge is your archetypal Kenyan gambler: intelligent, male, young, urbane and computer savvy. He is a recent graduate of Technical University of Kenya. He finished his BSc in IT studies just last year and told me that he was in the process of looking for a job. But as he looks for a job, he said, he is hooked to betting. “I will not lie to you – I cannot stop betting because I have become an addict.” Njoroge has been betting since 2013, when he first entered university as a freshman. “But I will also congratulate myself, I have been able to tame my betting mania to now just once a week,” said Njoroge. “I bet every Friday and I have cupped my betting to no more than KSh3,000. That is the maximum that I can bet.”

I asked Njoroge what was the highest amount he had ever won during his four years of betting. “Twenty-one thousand,” he replied. “I don’t play huge bets. For me to have won the KSh21,000, I had placed a bet of KSh1,000.” Since then, he has been winning small amounts ranging from KSh3,000 to 6,000. Was it out of choice that he was betting small money? I asked him. “Not really. It is because I have never had a huge lump sum. If I did, trust me, I would play in the big league. The bigger the odds, the greater the risk, the higher the reward,” Njoroge reminded me.

“Although I am not able for now to stay away from betting, I consider myself a safe bet,” said Njoroge. “I have been betting at Moha’s cyber for a while now and I know all my fellow gamblers. I do not consider myself a serial gambler.” Njoroge told me of a banker who worked at Kenya Commercial Bank who bet every single day. “His online account always has a floating minimum of KSh10,000 for placing his bets. Many times he has lost huge amounts, but he seems to have a constant supply of money. He does not seem to worry about his losses.” Every morning at 7am, his banker betting friend passes by at the cybercafé and places his bet before leaving for work. In the evenings, before going home, he passes by again and places more bets. “I think betting is like a sickness,” mused Njoroge. “I look at the banking fellow and I cannot believe that he often bets to win only KSh1,000 on top of his minimum KSh10,000.”

“Gamblers never have enough money. They are always begging and borrowing and are trapped in a vicious cycle of living in a make-believe world of delusion where they will wake up the next day and be declared a jackpot winner.”

Anthropologist Natasha Schull says, “For gamblers, it is not always the sense of chance that is attractive, but the predictability of the game that underpins the escapism. Even winning disrupts this state of dissociation.”

Before releasing Njoroge to go back to his computer machine, I asked him whether he was genuinely worried that his addiction would (finally) get the better of him. “That is why I am seriously looking for a job. I am hoping once I get a job, I will quit betting.” It sounded more of a wish than an expectation.

“But once you get a job, won’t you start earning some good pay and that may induce you into placing bigger bets? I mean you will now have the bigger cash you been craving for?” I asked him. “Remember what you told me about the greater the odds, the higher the reward?” He paused, then said, “Let me go back.”

A sickness

“Betting is a sickness, a sickness that can only be cured by oneself,” said Simon Kinuthia, a recovered gambler, who once lived in East London and came back home in 2008. It is in East London that he first learned how to bet and eventually got hooked. “Betting and gambling joints are all over the city of London. They are like your local neighbourhood kiosks here in Nairobi.” As a restaurant supervisor in East London, Kinuthia would use his break to dash to the nearest betting kiosk to place a bet.” He been back in Kenya for nearly ten years now, and says he would bet even his house rent and would be perpetually broke and always in debt “because you must always borrow to feed your addiction. Gamblers never have enough money. They are always begging and borrowing and are trapped in a vicious cycle of living in a make-believe world of delusion where they will wake up the next day and be declared a jackpot winner.”

With his colleagues, Kinuthia would bet in the morning, at tea break, during the lunch hour, in the evenings and even at night. “When we got our weekly pay, we would all head to gambling joints and bet the whole night. We would lose all our money, possibly only one of us would win his bets,” said Kinuthia. Yet, that did not deter them. “The more you lose, the more you want to place even more bets, erroneously believing it was not your lucky night. It is a paradox.”

Kinuthia, who is an accountant by profession, told me that betting is a business based on the understanding of probabilities. “What is the probability of a gambler winning the jackpot?” posed Kinuthia. “It is one out of 10 million, assuming every day 10 million Kenyans are placing their bets. In other words, your chances of not winning the big money is 99.9 per cent.” Many of these people, Kinuthia said, have little or no understanding of the probability of losses.

Kinuthia has faithfully kept away from betting in Kenya. “I saw people (in the UK) lose jobs, others got into manic depression. Others who could not live with the shame of losing everything they ever owned – after being auctioned – and of having mounting debts, committed suicide. “Betting is like being a drug addict: People begin using drugs as a leisure activity in the false belief that they can quit anytime, if the leisure becomes boring, or if they find something better to do,” said Kinuthia. “But no sooner do you start dabbling in drugs, then you realise you want more and more of the same. It is no longer a leisure activity, but an addiction that has to be fed to keep it going. That is precisely how betting works, even on the most innocent people, who cheat themselves they are doing it for fun, and if not for fun, at least then to win some money. They soon realise they are hooked onto an alluring activity that is intoxicating, that like a drug gives them a kick, or if you, like ‘a shot in the arm.’”

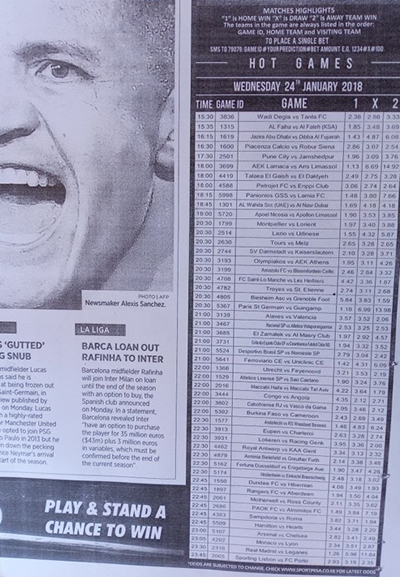

Social anthropologists have long observed that gamblers use their bets to chase losses and often they seek to be in a world where they can forget their problems. I found this to be true of my newspaper vendor friend, who has spawned a business idea from the betting mania: selling photocopied newspaper pages with “hot games” for betting. At KSh20 per page, the vendor mainly sells the information to security guards, casual labourers, matatu drivers and conductors, street vegetable vendors and hawkers, job seekers, as well as jobless Kenyans. All of these people’s dream is to win the jackpot and merrily transform their “miserable” lives by becoming instant millionaires. It is a dream fed daily by the fantastic news that a peasant women from Kakamega County can actually win KSh25 million from placing her bet correctly.

This paradox – of losing hard-earned cash in a betting game and instead of quitting, you immerse yourself even further in the quagmire is something I found prevalent among university students. To understand how the betting mania has caught on among Kenyan youth, I went to the University of Nairobi’s Chiromo campus, where science and medical students are housed. It is a campus for “serious students” who are not even supposed to have time to socialise. But with the onset of online betting in Kenya, Chiromo campus students have not been spared the craze.

Victor Rago, who is studying chemistry, admitted to me that the betting mania has afflicted his campus and is driving many students crazy. “Today students spend more time betting than they do in their academics. If only they spent half the time they did in analysing football matches so as to place the correct bets, we would have very many first class honours.” Rago told me about his roommate, who in their second year in 2017, placed his bet one Saturday afternoon with Ksh200. As luck would have it, by the evening his roomie was worth KSh250,000 sent to his smart phone. “I knew he had ‘struck gold’, because when he came to the room, he said he wanted us to go into town and eat some real food at some real restaurant. He excitedly told me he had won 250K and it was proper for him to take some time and enjoy life. For a whole semester he did not show up in the lecture theatre.”

Rago said students were now spending all their energies dreaming every single day about betting and winning bigtime money. It has become a full-time occupation for them. Studies have become secondary. “Here at Chiromo, there are betting groups, just like there are tutorial groups, but the betting groups are superseding the tutorial groups by the day,” said Rago. I asked him why many of these betting groups are mostly composed of male students. “Male students are ardent football followers, which they have done for a long period, so they have a knack for better and greater analysis and I also suspect they are not averse to risks.”

But that does mean female students do not bet, said Rago. “They do, but they are not in the forefront. And, because they are not as adept analysts like their male counterparts, they rely on ‘seasoned analysts’ to predict for them.” Many of the so-called seasoned analysts run online advisory chats on Telegram applications. “They are also WhatsApp advisory chats, but many gamblers prefer the Telegram app,” said Rago. He said the Telegram app is preferred because your contact details are not exposed to everyone. Unlike WhatsApp, where, if you have to belong to a chat group, you must share your mobile phone number, the Telegram app is created such that it is controlled by a sole administrator and he or she does not need to know your telephone number to chat with his or her clients.

Professional predictors

“One of the biggest of these Telegram app online ‘professional predictors’ is called Binti Foota,” said Rago. Ostensibly targeted at females who do not have the time to analyse or follow football matches religiously, it has an accumulated a following of nearly 19,000 gamblers. “What the betting craze has done is to spawn another industry, which is feeding into the gambler’s addiction,” said Rago. “So, for KSh530 a fortnight, Binti Foota can help you predict the outcome of football games. If you pay her KSh1,030, the site can predict for you for 34 days.” Rago said many of the female students who bet make the bulk of Binti Foota chat followers. “Binti Foota’s identity is not known, neither does she have to know the identity of her clients. So, if you are dissatisfied with her analyses, what you can do is migrate to another prediction site, or bad mouth her on a different site,” said Rago.

Social anthropologists say that the social costs of gambling are huge, and include bankruptcy, homelessness, suicide and domestic violence.

The student told me these online “professional predictors” had been infiltrated by online scammers, who have been conning people of their money in the guise of helping them place winning bets. “Many of the so-called online analysts and professional predictors are just scammers preying on the gambler’s addiction.” Scammers from as far as Nigeria have opened Telegram chat groups that pronounce how they have helped people win hundreds of millions of shillings. And because people are predisposed to greed, they fall prey to such scams,” said Rago.

He added that because of the obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) behaviour displayed by the student gamblers, most of these students tend to neglect their studies and suffer from pendulum-like mood swings that are unpredictable. Rago told me of the Kenyatta University second-year student who committed suicide last year. “The student bet all his tuition fees – KSh80,000. What he did was to place two bets: KSh40,000 each. The odds were high, but he took the risk, convinced he would at least win one gamble. When he lost both bets, his world came crumbling down.”

Social anthropologists say that the social costs of gambling are huge, and include bankruptcy, homelessness, suicide and domestic violence.

The bigger the odds, the greater the risk, the higher the rewards is a principle many gamblers abide by, hoping to cash in on the odds they have placed. Many times, the risk is not worth it, “but then”, said Rago, “gambling is a compulsive behaviour disorder that overtime grips gamblers, who like alcoholics, to cure their alcoholism, must first accept they are suffering from an alcohol problem. Gamblers must also come to terms with their odd behaviour that drives them to bet compulsively.”

A consultant periodontist described to me how self-destructive compulsive behaviour disorder can be. A part-time lecturer, he narrated to me how one of his best students pulled out of class in his third year. “Aaah daktari, this course is taking too long: my peers are making money out there and here I am slogging through an unending degree course,” the student replied when he asked him why he had decided to pull out of medical school. “To my consternation, I did not know he had been betting on the side,” the consultant said. “I was told that his friends were boasting to him that by the time he is finished with his medical degree, they would be owners of real estate and funky vehicles.” His friends apparently were full-time gamblers and some had shown him their bank slips.

The consultant said he should not have been overly surprised: some of the young doctors known as registrars have become master gamblers. “In between their clinical rounds in the hospitals, the physicians are glued to their smart phones busy betting, so much so that one would be inclined to think that betting is one of their examinable units.” But the most shocking revelation came when he learned that some parents were encouraging their children to bet, oblivious of the dangers they are getting their children into.

Sports betting

I met a senior-level manager at one of the better known sports gaming companies for a chat in their posh offices in Nairobi. If a company’s employees is an indication of who its clientele might be, this sports gaming company told it all: The employees I saw were young – hardly more than 33 years-old with a look that declared: “We are here, we have arrived”. “It is not true sports gaming companies are impacting negatively on the Kenyan society, much less its youth,” he ventured to tell me. “This is a wrong notion that is being perpetrated by the mainstream media. It has become all hype and no substance. What I want are facts and figures, not emotional lurid stories.” He reeled off from his head the statistics from a recent poll conducted last November to find out how Kenyan youth are spending their money. “The survey, GeoPoll, showed that 26 per cent of the youth spend their money on saving and expenditure and only five per cent spent their money on betting. Which youth is this that is being destroyed by betting? The Kenyan media is obsessed with sensational reporting,” said the manager.

Implications of Sports Betting in Kenya – a study conducted by Amani Mwadime and submitted to the Chandaria School of Business at the United States International University in Nairobi in 2017, estimates that 2 million people in Nairobi alone participate in online betting.

The manager, who is not authorised to talk to the media, described betting as an entertainment and said people are entitled to some fun, some leisure, albeit in a controlled environment. “We operate under the rules and obligations of the Betting Control Licensing Board. We are therefore legitimate. What is destroying the youth is not sport gaming companies – on the contrary – it is the so-called amusement machines that are now found all the over the place, including villages in some far-off counties. Those machines are the problem: they are illegal, unregulated and accessed by all and sundry. Of course, most of them are used by pupils and students alike, who are yet to be of the adult age, that is above 18 years. That is what the government and the media should be concerned with and not licensed, legal betting companies,” pointed out the manager. The government should clamp down on these machines, not ask sports gaming companies to part with astronomical taxes – “it just does not make sense. We are a business, not a philanthropic company. The government is being unreasonable when it says sports gaming companies are making so much money, so they have to pay taxes that are pegged to their turnover. It never happens anywhere in the world.”

Implications of Sports Betting in Kenya – a study conducted by Amani Mwadime and submitted to the Chandaria School of Business at the United States International University in Nairobi in 2017, estimates that 2 million people in Nairobi alone participate in online betting.

The manager said his company has a cap on the amount one can bet in a day: KSh20,000. “I should let you know, we are not reckless. We also do not want people to overstretch their enjoyment.” Sports gaming companies and casinos consider gambling a “victimless” recreation, and therefore, a matter of moral indifference.

The sports gaming companies are up in arms because the government has asked them to pay 35 per cent on their monthly turnover in taxes. “And do not forget we still have to pay the annual 30 per cent corporate tax. Some people are misadvising the government,” said the manager. This “misadvising” began last April, 2017, when Henry Rotich, the Treasury Cabinet Secretary, proposed a 50 per cent tax on sports gaming companies when he presented the national budget. He also came up with the Finance Bill, which President Uhuru Kenyatta refused to sign, insisting sports gaming companies ought to pay the 50 per cent tax.

Social scientists agree that gambling blurs the distinction between well-earned and ill-gotten wealth.

When the matter was taken up by Parliament, it was shot down; parliamentarians rejected the 50 per cent tax idea and said that the tax should remain at 7.5 per cent. “Now we don’t know where this 35 per cent is coming from. There is a misconception about sport gaming companies in this country: That we make abnormal and humongous profits. The most profitable company in Kenya is Safaricom. I have not heard the government say, since Safaricom makes billions of shillings, they should pay higher taxes than what they are paying currently, because they happen to be making tonnes of money.”

I told the manager that my preliminary inquiries on the betting mania, especially among the youth, is that it is distracting them from productive activities, be it studies or work. I also told him that betting is unwittingly creating among the most productive cadre of Kenyans a false notion that gambling can be considered an economic activity.

“Kenya is not a theocracy and gambling has existed in independent Kenya for the last 50 years,” shot back the manager. “Where is all this hullabaloo about sports gaming companies coming from suddenly? I sense business envy here from some (powerful) quarters. Could be it that some people are sore because they cannot believe they missed an opportunity to make money?” The manager told me that a tycoon close to the powers that be fought one of the sports gaming companies when it started its operations, arguing that these companies were corrupting the morals of the youth. There are currently 25 sports gaming companies in Kenya, according to latest Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) statistics, which were compiled last year in June.

“The argument about morals is both laughable and superfluous,” said the manager. “What then should we say of alcohol? Shouldn’t the government then shut down all the bars and drinking dens to curb alcoholism? What about beer and liquor manufacturing companies? Shouldn’t the government tax them an arm and a leg because they encourage our youth to drink? Alcohol is not only harmful to their health, but also leads to anti-social behaviour.” The morality argument falls flat on its face, said the manager. “That is the province of the purveyors of heavenly realm. I have not heard them say betting will take the youth to hell or that they are engaged in a sinful activity. ”

The manager dispelled the notion that betting and gambling are reckless behaviour. “Life is about gambling. Did you know prayer is a gamble? Everyday people are offering prayers to God, which are not fulfilled. Yet, they continue praying and they will not stop. At least we fulfil part of our bargain by paying people for their gambles. I can tell you this without a shadow of a doubt, we are going to create millionaires like no industry has done in modern Kenya.”

Anecdotal evidence shows that online betting is impoverishing poor people and reducing their levels of productivity. Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi, the Director General of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), recently observed: “:….you are seeing sports gambling in Kenya today, but nobody is telling the gambling firms not to accept money from poor gamblers. It is the poor who must be told that they will live with the consequences of dreaming that gambling is an investment.” It is a fact that gamblers are drawn disproportionately from the poor and the low-income classes, who can ill afford to gamble: they are susceptible to the lure of quick imagined riches. This class of people are in financial doldrums and other societal tribulations that make them vulnerable to fantastic dreams of sudden wealth.

A tax expert who did not want his name revealed said, “One of the sports gaming company’s act of sponsorship withdrawal can be interpreted as an act of industry intimidation. The company is taking advantage of the fact that there is no direct evidence attributing societal problems to its activities.” Sportpesa, one of the better known gaming companies, withdrew its sponsorship of 10 sporting entities in Kenya that it was supporting after the government asked all sports gaming companies to pay an upgraded tax of 35 percent.

The tax consultant pointed out that Chapter 12 of the Kenyan Constitution on public finance management requires the creation of a tax system that promotes an equitable society. “Translation: Sports gaming companies such as Sportpesa are obliged to engage in good management practices by not holding the country to ransom, and using scaremongering tactics and threats such as job losses, withdrawing to another country or jurisdiction.”

Social scientists agree that gambling blurs the distinction between well-earned and ill-gotten wealth. I thought of the young man Njoroge – smart and forward-looking – yet, gambling, a debased form of speculation, had reduced him to lusting for sudden wealth that is not linked to the process that produces goods or services. Through gambling he hopes to grow wealth without actually working for it.