Kenya’s fiscal policy – the means by which the government adjusts its spending levels, revenue generation and collection, and debt to monitor and influence the economy- has been a defining feature of the current administration. The three have been characterised by almost consistent features and trends.

Some background information is useful. Kenya has had an annual growth rate of about 5.46 percent from 2004 until 2016. Initially, the economy was slated to grow at around 6 percent in 2017 but this has since been revised to 5 percent. According to Genghis Capital, it will actually be between 4.25- 4.75 percent due to the drought-induced contraction in agriculture, the negative effects of the interest rate cap on the financial sector and the prolonged electioneering period. The Government thinks the economy will grow by over 6 percent next year though the World Bank projects a lower rebound to 5.8 percent in 2018 and 6.1 percent in 2019.

Kenya’s economy is primarily services driven and according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), under the Kenyatta administration, growth has largely been on the back of government spending on infrastructure projects such as the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR), the expansion of the road network as well as electricity generation and transmission projects. Other significant contributors to growth include a resurgent tourism industry and growth in information and communication, real estate and transport and storage.

Over the past 6 years, government spending has grown at an average of 14.7 percent, yet revenue growth has only increased by 12.7 percent. Under the current administration, spending has gone up by two-thirds, from Sh1.6 trillion in 2013/14 to Sh2.64 trillion in 2017/18.

Back to fiscal policy, we will address each component separately: expenditure, revenue generation and collection, and borrowing.

Expenditure

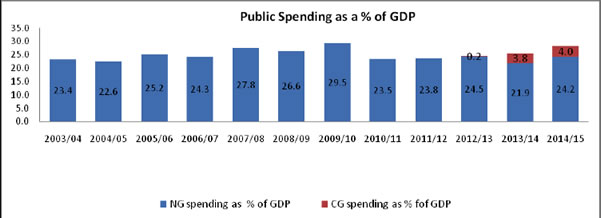

Over the past 6 years, government spending has grown at an average of 14.7 percent, yet revenue growth has only increased by 12.7 percent. Under the current administration, spending has gone up by two-thirds, from Sh1.6 trillion in 2013/14 to Sh2.64 trillion in 2017/18. While some of this can be explained by inflation reducing the value of money, there is a consistent trend of notable increases in government spending.

(Source: Institute of Economic Affairs)

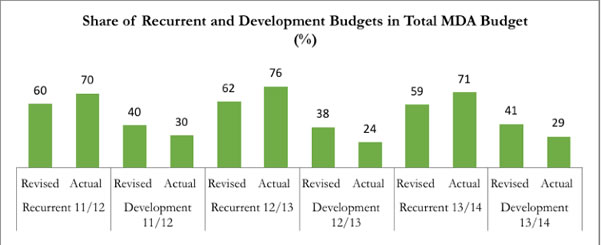

A fundamental problem in analysing fiscal policy at both national and county levels is determining the intended recurrent vs development budgets and comparing these to the actual expenditure pattern. The image below from the Institute of Economic Affairs Kenya (IEA) details this for the National Government:

(Source: Institute of Economic Affairs)

Overall, two key trends are clear, the first of which is that the national budget is still geared towards recurrent spending. Indeed, as the Treasury itself has admitted in the past, recurrent expenditure is reaching unsustainable levels.

There are several factors behind this aggressive growth in expenditure, the first of which is devolution. In 2010 Kenyans enacted a new constitution, which established a bicameral Parliament and 47 county governments. At the beginning of the implementation of devolution, a parliamentary report indicated that it would cost at least Sh36 billion to set up. Prior to devolution, it cost Sh6.6 billion per year to run Parliament, but that figure is expected to rise to Sh14.3 billion. The Parliamentary Budget Office has also stated that it will cost Sh21.75 billion annually to run the 47 county assemblies. Thus, while welcome, the reality is that devolution is expensive.

At the beginning of the implementation of devolution, a parliamentary report indicated that it would cost at least Sh36 billion to set up. Prior to devolution it cost Sh6.6 billion per year to run Parliament, but that figure is expected to rise to Sh14.3 billion. The Parliamentary Budget Office has also stated that it will cost Sh21.75 billion annually to run the 47 county assemblies. Thus while welcome, the reality is that devolution is expensive.

Linked to the point above is the public wage bill which, according to the Salaries and Remuneration Commission (SRC), has ballooned from Sh465 billion when the Kenyatta administration took over to Sh627 billion in the 2015/2016 financial year, an annual average growth of 9 per cent. SRC’s projections show that it will be Sh676 billion in 2016/2017. Earlier this year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) raised concerns, stating that Kenya is among countries that exhibit large increases in the wage bill, particularly in the run-up to elections. IMF is of the view that given Kenya’s rising debt levels (more on this later) the decision to increase spending on public sector wages is a concern as less funds are left over for economically productive development expenditure. The SRC pooh-poohed the IMF’s concerns, stating that wages were actually falling as a proportion of GDP: from 10.3 per cent in 2012/2013 to 9.5 per cent in 2015/2016.

A second factor behind the growth in expenditure, which the government has been eager to finger as the primary reason, has been the investment in infrastructure. According to the Capital Markets Authority (CMA), Kenya’s current estimated infrastructure funding gap is USD 2-3 billion per year over the next 10 years. To address this, government has allocated nearly a third of total budget expenditure to infrastructure between the 2016/17 and 2019/20 financial years.

The World Bank makes the point that the infrastructure investment drive in Kenya needs to be done in a way that is both efficient and sustainable. With such a robust commitment, key questions must be asked. For example, is Kenya investing in the right infrastructure? The Brookings Institution makes the point that a push for more infrastructure only raises economic growth and people’s well-being if the focus is on quality and impact, rather than quantity and volume. Has Kenya fallen short here? Has the government conducted an audit of infrastructure investment and the development it has engendered thus far? Has there been an audit of its quality? How efficient is our investment? Without an answer to these questions, the country risks wasting resources on aggressive infrastructure expenditure that generates no real benefits for its people.

Indeed, the link between infrastructure and economic growth is more tenuous than previously assumed. According to the London School of Economics, most recent studies on infrastructure’s contribution to growth tend to find smaller effects than those reported in earlier studies; this is linked to improvements in methodological approaches. Kenya, therefore, shouldn’t assume that infrastructure investment and development will automatically lead to significant improvements in economic growth. It is time for a fundamental rethink of the scale, nature and efficiency of the government’s spending on infrastructure.

Kenya, therefore, shouldn’t assume that infrastructure investment and development will automatically lead to significant improvements in economic growth. It is time for a fundamental rethink of the scale, nature and efficiency of the government’s spending on infrastructure.

The final issue regarding expenditure is linked to the mismanagement of public funds at both national and county levels. At the national level, allegations of corruption and financial mismanagement are legion and include: the National Youth Service (NYS) affair where the Auditor General stated a loss of Sh1.9 billion; Sh5.2 billion misappropriated at the Ministry of health according to an in-house audit report; mobile clinics valued at Sh1.4 million each being sold to the government at more than 7 times the price then abandoned in an NYS yard; inflated rig charges at the Geothermal Development Company (GDC) in which the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) found the tender committee culpable and six managers were sent on compulsory leave.

At county level, there are rising concerns with expenditure considering that the national government has sent to the counties more than Sh1 trillion since their establishment in 2013. Research by the International Budget Partnership Kenya (IBPK) reveals that county governments are not making available fiscal documents required by the Public Financial Management Act (PFMA). Only about 20 percent of key budget documents, including fiscal expenditure documents, meant to be online had been uploaded. Indeed, IBPK reports that in some cases, budget allocations are based on lists of projects drawn up by Members of County Assemblies (MCAs). There is no clarity on the criteria governing such allocations, and even less clarity on how county funds are actually spent. There is a distinct air of mischief informing this laxity. It is not a secret that the first iteration of devolution revealed how much autonomy county governments have in the planning and use of funds they receive and generate. This lack of transparency seems to be aimed at facilitating a culture of financial mismanagement and corruption at the county level in an environment where, frankly, no one is holding them accountable.

Further, county governments see themselves as expenditure units, not development units. This needs to change. Rather than concentrating on how much they have to spend, they ought to focus on the development dividends they are responsible for generating. Without this fundamental shift in thinking, county governments will continue to be like spoilt children, forever crying over what they are owed, but with nothing to show for the development they ought to deliver.

For example, 16 firms listed on the Nairobi Stock Exchange issued profit warnings in 2016, which meant less corporation tax could be collected. Additionally, the 7000 jobs lost to downsizing and shuttering of firms, mainly in the banking sector, reduced Pay As You Earn receipts.

The greatest concern beyond the moral question of the financial mismanagement of the public funds of a poor African country, is the issue of how corruption affects spending efficiency. As will be explained later, Kenya is getting into significant debt, particularly to finance development expenditure. If such debt is not being used as efficiently as possible and instead funds are stolen or dubiously spent, the country will be saddled with onerous debt without he means – the improvements in economic performance that were to come from debt financed development projects – to pay it.

Given the factors detailed above, there are several broad changes that ought to be made. At national level, the first recommendation is for government to commit more money to development expenditure and put more effort into actually absorbing the allocations given to the docket.

Secondly, the national government ought to be more consistent in the manner in which it presents data and should make it easier to track planned versus actual expenditure, particularly across the recurrent and development dockets.

Thirdly, large allocations to infrastructure projects need to be audited and a determination made on the effectiveness of the allocations, how funds can be better spent and recommendations on how to improve efficiency.

Finally, national government has to clamp down on financial mismanagement and prosecute and punish culpable officials. Without this, the government’s commitment to ending corruption will be seen as insincere and ineffective.

At county level, there are several issues that ought to be addressed the first of which is that there needs to be a very clear hierarchy of accountability for county expenditure. Governors and the County Ministers of Finance must be held accountable for their spending and individuals need to be punished if found guilty of corruption.

Secondly, counties must comply with the PFMA and provide breakdowns of their expenditure which includes a delineation between recurrent and development expenditure.

Thirdly, the principle of fiscal discipline should carry considerable weight when national government makes county allocations such that responsible use of resources is rewarded and poor performers are punished.

Finally, a citizen-led effort to create a ranking of county governments according to fiscal transparency with a focus on expenditure would likely create pressure on county governments to adhere to their legal obligations. Included in the ranking should be how well they comply with PFMA stipulations, with the top and bottom performers widely publicised.

Revenue Generation and Collection

Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) has been falling short of its revenue targets for some time. For example, in 2016/17 total collection stood at Sh1.365 trillion representing a performance rate of 95.4 percent, and a shortfall of Sh66.64 billion- a significant number. In the first four months of this fiscal year, KRA has already fallen behind by Sh40 billion. There are questions as to why revenue collection consistently underperforms. I am of the view that KRA is given unrealistic targets, more informed by aggressive increases in government expenditure and oblivious to the serious constraints that mute tax collection.

Without this fundamental shift in thinking, county governments will continue to be like spoilt children, forever crying over what they are owed, but with nothing to show for the development they ought to deliver.

Revenue generation targets tend to be revised upwards over the course of the year. KRA’s original revenue target for the 2016/17 was Sh1.415 trillion which was later revised to Sh1.431 trillion, an increase of KES 16.24 billion. This is a concern because motivations behind the increases in targets are not clear. Do they perhaps stem from a realisation in Treasury that it cannot raise as much as anticipated in borrowing?

The second constraint is that the macroeconomic environment informs the extent to which revenues deviate from targets. For example, it is estimated that a 1 percent reduction in GDP growth reduces revenue by Sh13.4 billion and as noted earlier, this has been something of a tough year. A similar increase in inflation also requires that revenue targets be raised by Sh13 billion.

This is linked to sectoral issues which can affect the ability of KRA to collect tax. For example, 16 firms listed on the Nairobi Stock Exchange issued profit warnings in 2016 –a rising trend since 2013– which meant less corporation tax could be collected. Additionally, the 7000 jobs lost to downsizing and shuttering of firms, mainly in the banking sector, reduced Pay As You Earn receipts.

Third, government policy decisions, particularly those related to tax policy, affect the ability to generate revenue. For example, the non-implementation of changes to specific excise rates in 2016/17 reduced revenues by nearly Sh5 billion. Additionally, the duty-free importation of essential foods (maize, milk, sugar) led to a revenue loss of over Sh4 billion in the fourth quarter of the same financial year. Indeed, it is estimated that government policy decisions cost it Sh13 billion in lost revenue that entire year. The government tends to shoot itself in the foot in other ways too. For example, delays in remitting income tax from public institutions costs it Sh823 million.

Finally, revenue generation and collection in Kenya like the rest of Africa is negatively affected by illicit financial flows from the country. According to the UN, Africa loses more than US$50 billion through illicit financial outflows per year. Companies evade and avoid tax by shifting profits to low tax locations, claiming large allowable deductions, carrying losses forward indefinitely, and using transfer pricing.

The main reason why consistent subpar revenue collection is worrying is because the national treasury continues to construct budgets based on the unrealistic targets. For example, revenue generated was meant to play a bigger role in the current budget, financing 60.7 percent of the overall deficit and 58.7 percent of the development expenditure. Since it appears as though targets will again not be met, government will have to borrow more than anticipated.

There ought to be fundamental rethink of revenue generation and collection in order to effect a sustained increase. There are several factors to address, the first of which is improvements in the business environment that increase profits and thus taxable revenue. A key component that is often ignored here is the environment for the informal economy. Current assessments largely ignore the sector in which 90 percent of employed Kenyans earn a living. More ought to be done to make informal businesses more profitable.

At the same time, the government ought to seek to expand the revenue base by encouraging the formalisation of these businesses. Concerted efforts must be undertaken to pilot schemes that remove barriers to – and create incentives for – formalisation, particularly of larger businesses that easily evade tax yet are robust enough to consistently pay.

As recommended by the Africa Progress Report 2013, alongside demanding the highest standards of propriety and disclosure from their government, Kenyans should push citizens of the developed world to demand similar standards from their governments and companies.

Finally, Kenya needs to work on curbing illicit financial outflows. The UN makes the point that G8 leaders have committed to the 2013 Lough Erne Declaration, a 10-point statement calling for an overhaul of corporate transparency rules. Among other things, the declaration urges tax authorities to automatically share information to fight evasion. It states that poor countries should have the information and capacity to collect the taxes owed to them. Kenya should join other African countries in lobbying rich countries to enact stricter laws against tax evasion. As recommended by the Africa Progress Report 2013, alongside demanding the highest standards of propriety and disclosure from their government, Kenyans should push citizens of the developed world to demand similar standards from their governments and companies.

Borrowing and Debt

In 2013, the Jubilee administration inherited a debt of Sh1.7 trillion after a decade of the Kibaki government. Less than 5 years later, that has ballooned by nearly 250 percent to Sh4.4 trillion. This year’s borrowing has been particularly aggressive. The Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) says that the government is borrowing an average of Sh86 billion per month, the highest level since the bank started listing public debt in 1999, and over Sh30 billion more than the monthly averages of 2015 and 2016.

Despite this, it seems the government’s debt appetite won’t wane any time soon. The Treasury recently announced that it is seeking to issue another Eurobond, which could be used to repay the outstanding US$750 million syndicated loan the government raised in 2015 and which came due in October. What seems to be clear is that given expanding expenditure and subpar revenue collection, borrowing from both foreign and domestic sources will continue to grow. Further, as a Bloomberg analyst points out, Kenya has among the highest debt levels in sub-Saharan Africa, partly a result of having neither the commodity revenue sources of Nigeria and Angola nor the budget support from donor countries enjoyed by neighbouring Tanzania and Uganda.

Before looking at the specific features of Kenya’s debt, it is important to state that debt itself is not necessarily a problem. If used wisely, it can fund investment into activities and projects that catalyse economic development, GDP growth and growth in per capita incomes. Concerns only start being raised when the pattern of debt accrual and servicing seems headed in an unsustainable direction. If expenditure is growing in the context of muted revenue generation, that creates momentum for more debt than cannot be sustainably serviced. Further, if debt is not used efficiently and linked to increases in productivity and GDP growth, it also saddles countries with burdensome repayments. At the moment, Kenya is on the cusp where the government can either take decisive action to put the country on a better debt path, or continue with current trends that are edging the country closer to an unsustainable position.

The IEA points out that as of June 2012, total public debt was composed of 52.9 percent domestic debt and 47.1 percent external debt. However, the share of external debt has been steadily growing and recent statistics show that today the situation is reversed, with external debt taking up more than half (52.3 percent) of total debt.

The National Treasury Report 2015 indicates that the external debt stock for Kenya is composed of multilateral debt (54.7 percent), bilateral debt (27.1 percent), export credits (1.5 percent), commercial banks (0.6 percent) and International Sovereign Bonds (16.1 percent). As the IEA points out, a large part of the external debt remains concessional (i.e. on terms substantially more generous than market loans) and mainly from multilateral creditors; however, the share of concessional loans has been falling over the last three years which means external debt is becoming ever more expensive for the country.

There are several factors affecting the composition of debt, the first of which is Treasury’s desire to reduce domestic borrowing in order to release domestic credit for the private sector. This was a major reason given for issuing the Eurobond. As shown by the statistics above, he government has stayed true to this intent in some ways. However, the cap on interest rates introduced last year, has perversely facilitated government’ ability to raise domestic debt as banks, reluctant to lend to the general public due to profit margin and risk concerns, have more aggressively pursued government securities. The attractiveness of government debt is thus pushing the domestic private sector out of the domestic debt market, which contradicts government’s original intent.

The Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) notes that the government is borrowing an average of Sh86 billion per month, the highest level since the bank started listing public debt in 1999, and over Sh30 billion more than the monthly averages of 2015 and 2016.

It is important to note that, as reported in The Standard, World Bank data indicates that the average grace period on repaying new external debt has shrunk by half in the last four years. On average, in 2013, the country was given 8.2 years before starting to repay loans. This had reduced to 4.6 years by 2016. Shorter grace periods reduce the government’s room for flexibility and could be an indicator of jittery lenders keen on getting their money back as soon as possible. Indeed, Bank of America Merrill Lynch notes that Kenyan debt underperforms its peers as evidenced by the fact that yield premiums over U.S. debt have not narrowed as much as those of other sub-Saharan debt. In short, Kenya is seen as riskier to lend to than other African countries.

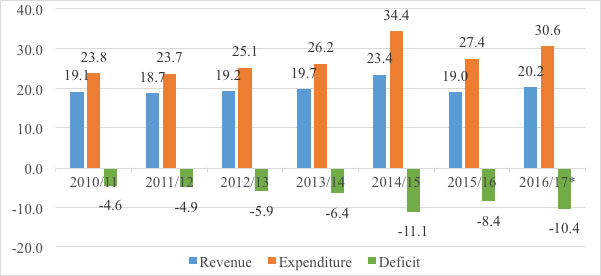

Informed by the expansion in borrowing, Kenya’s fiscal deficit has also grown. Its ratio to GDP has widened significantly from 6.4 percent in 2013/14 to 10.4 percent in 2016/17. The IEA points out that the large increase in deficit partly reflected the financing of the first phase of Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) project.

Fiscal deficit as a percentage of GDP

(source: IEA)

The government is targeting a fiscal deficit of 5.9 percent of GDP, in the 2018/19 fiscal year, down from an estimated 7.3 percent this fiscal year. Others however do not expect this will be met. Genghis Capital thinks Kenya’s budget deficit for this fiscal year will likely reach 8 percent of GDP. Further, the government doesn’t always hit its fiscal deficit projections. Indeed, according to Cytonn Investments, in the 2016/2017 fiscal year, the government’s deficit actually widened to 8.3 percent of GDP, some way above its revised target of 6.9 percent. In any case, despite the efforts it may be making to reduce the deficit, current government targets and performance are still higher than its own preferred ceiling of 5 percent.

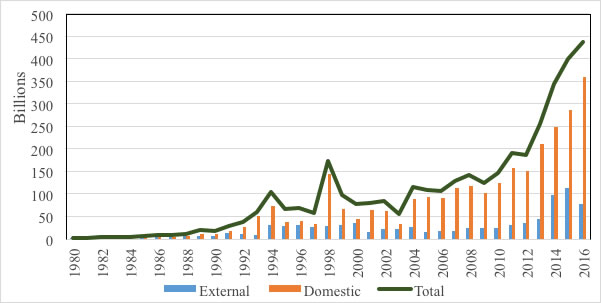

The IEA points out that as the amount of debt held increased, the cost of debt has also gone up with debt servicing increasing from about Sh19 billion in 1990 to Sh400 billion by the end of 2015. A larger component of debt servicing emanates from servicing of domestic debt, but since the proportion of domestic and external debt to GDP are almost at par, it may indicate that it is costlier to service the former.

Debt service 1980 – 2016, KES billions

(Source: IEA)

There are growing concerns as to how much revenue is being committed to servicing debt. In the first nine months of the 2015/16 financial year, the government spent four out of every 10 shillings it collected as tax to settle debts. In April, the IMF estimated Kenya’s debt-service to revenue-ratio at 34.7 percent against a threshold of 30 percent, and a report in the Business Daily pointed out that in the last fiscal year, the country spent more money to settle debt (Sh435.7 billion) than it did to finance development (Sh394.2 billion). If more and more revenue has to be locked into servicing debt, government will either have to ramp down spending on development (given the relatively fixed burden of recurrent expenditure) or borrow even more, none of which is good.

The IEA also notes that the ratio of debt to GDP rose from 40.7 percent in 2012 to 56.4 percent in June, which merited a ranking of 78 out of 138 countries on the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index.

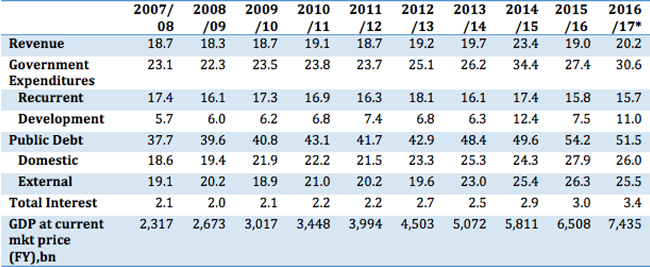

Government Budget and Public Debt as % of GDP

(Source: IEA); GDP is for full year (FY) and measured in thousands; * Provisional estimates

As borrowing continues to grow aggressively, it will lead to higher imbalances that will raise concerns about sustainability.

Views differ on whether Kenya’s debt is sustainable. Some are of the view that given the massive gaps in key sectors such as energy and transport infrastructure, the country must continue to do everything possible to finance and address the gaps and that debt accrued now will pay off in the long term. Kenya remains below the World Bank’s debt-to-GDP ratio ceiling (or tipping point) of 64 percent. The IMF, in its review of Kenya a year ago, said Kenya’s risk of external debt distress remains low but notes there is need for reduction in the deficit over the medium term. While the IMF has raised concerns about Kenya’s public debt, it is below what they view as the applicable ceiling for Kenya – 74 percent of GDP.

The IEA points out that as the amount of debt held increased, the cost of debt has also gone up with debt servicing increasing from about Sh19 billion in 1990 to Sh400 billion by the end of 2015.

Others, however, are of the view that a debt-to-GDP ratio beyond 40 percent for developing and emerging economies is dangerous. The IMF itself envisages fiscal consolidation that targets a 3.7 percent of GDP deficit by 2018/19 (compared to the government’s own target of 5.9 percent) which it says is critical to maintaining a low risk of debt distress while preserving fiscal space for development priorities.

I disagree with the Treasury’s assertions that the national debt is manageable and that there is headroom for more. Kenya’s debt is only manageable if decisive action is taken to reduce expenditure, boost revenue collection and reduce borrowing. If this does not happen within the next three years, the country will start feeling the effects of debt distress.

The credit rating agency Moody’s has already raised concerns about the country’s accumulating debt. Indeed, the agency is currently assessing whether it needs to downgrade the country’s credit rating from the current B1 status on grounds of its weakening ability to repay debt. Moody argues that unless a decisive policy response is introduced, the upward trajectory in government debt will see the debt-to-GDP ratio surpass the 60 percent mark by June 2018, pushing financing costs for the private sector even higher. Its assessment points to the fact that in the latest fiscal year, the government spent 19 percent of its revenues on interest payments alone, up from 10.7 percent five years ago. It notes that persistent, large, primary deficits and high borrowing costs continue to drive government indebtedness ever higher. Further, government liquidity pressures risk, the danger that the government may not have enough readily available cash to settle its immediate and short-term obligations, is rising in the face of increasingly large financing needs.

Another credit rating agency, Fitch, has also indicated that it could downgrade Kenya’s rating due to its debt position. Fitch noted that the country was spending a larger proportion of its revenue on paying debt compared to its economic peers such as Uganda, Rwanda and Ghana.

Fitch gave Kenya a B+ rating, with a negative outlook. These credit ratings are important as a fall in rating will mean any new foreign debt taken on by the country will be more expensive.

There are several broad strategies Kenya can use to better manage its debt the first of which is to aggressively reduce expenditure. Government must implement austerity budgets and limit unnecessary expenditure. I also think here should be a fundamental downward review of salaries of those in government. While those of technocrats such as Cabinet and Permanent Secretaries as well as professionals such teachers and doctors should remain attractive, there are far too many people in elected office on overly generous terms, and the related wage bill is not sustainable for a relatively poor African country.

Secondly, government needs to improve its recurrent vs development expenditure allocations. As elucidated before, year after year, more money is allocated to recurrent expenditure which is not economically productive. A reduction in recurrent expenditure is crucial and this can be partially addressed by a downward review in wages as explained above. The IEA points out that although in relative terms the proportion of recurrent expenditure to GDP has slightly declined while that of development expenditure has nearly doubled from 5.7 percent of GDP in 2007/8 to 11.0 percent in 2016/17, recurrent expenditure still remains comparatively high.

In April this year, the IMF estimated Kenya’s debt-service to revenue-ratio at 34.7 percent against a threshold of 30 percent, and a report in the Business Daily pointed out that in the 2016/17 fiscal year, the country spent more money to settle debt (Sh435.7 billion) than it did to finance development (Sh394.2 billion).

Development expenditure should be prioritised by considering projects which bring immediate returns to the economy. More money must be committed to spurring the growth required to pay debts, if Kenya is to avoid a repayment crisis.

Thirdly, government has to create strategies to ensure more development expenditure is absorbed. A November 2017 report by Controller of Budget showed the use of development funds for the financial year ending in June was at 70 percent, the highest since 2013. While this is good news and higher than the 66 per cent rate recorded in the previous year, it is not good enough. Indeed, the organisation Development Initiatives notes that the 2017/18 fiscal year actually saw a decline in total allocations to development spending by 12.3 percent, as a result of lower absorption of development spending by ministries in 2016/17. The problem is at both national and county levels. As Price Waterhouse Coopers points out, if the entire amount allocated is not being absorbed, it defeats the purpose of the budget especially around development expenditure. Given that the country is getting into a great deal of debt for development expenditure, it is crucial that absorption rates in this docket increase in order to spur economic growth.

Fourthly, government needs to better track how the debt which is financing the development docket, is being used. Given concerns with financial mismanagement of public funds at both national and county levels, it is crucial that the debt spending is meticulously tracked. This is because financial mismanagement of debt funds poses the dangerous risk of pushing the country into debt unsustainability as money is pocketed rather spent to generate growth.

Conclusion

This article has elucidated Kenya’s fiscal policy and position in terms of expenditure, revenue generation and debt accrual. It is important that the country reduces expenditure, increases revenue generation and better manages debt spending to put the country on a more sustainable fiscal path. We are in a position where Kenya’s fiscal health can be dramatically improved by taking decisive action as per the recommendations herein. It is my hope that the government takes the required action to improve the country’s fiscal path so that fiscal policy plays the positive and important role it can in driving the country’s development.