Two road crashes in the first two weeks of November have robbed Kenya of six lives including that of Nyeri Governor, Wahome Gakuru, and once again brought to the fore the crisis of safety on the country’s roads and highways.

As of November 8, according to statistics released by the National Transport and Safety Authority, 2,387 people had lost their lives on our roads. In its 2015 Global Status Report on Road Safety, the World Health Organisation shows Kenya’s roads are amongst the most dangerous in the world claiming an average of 29.1 lives per 100,000 people. By comparison, Norway, which has significantly more cars on its roads had just a tenth of Kenya’s average fatalities per 100,000. Road crashes are among the top ten killers of Kenyans, account for between 45 and 60 percent of all admissions to surgical wards and cost the country up to 5 percent of GDP.

It’s not all doom and gloom though. While the number of registered vehicles on the roads nearly doubled between 2008 and 2012, from just over 1 million to just under 1.8 million according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, the total number of both accidents and victims actually fell by about half says the 2015 study Analysis of Causes & Response Strategies of Road Traffic Accidents in Kenya. However, what should set off alarm bells is that despite this, the number of deaths barely budged. It may only make the news when crashes either involve large numbers of people or a prominent person is killed, but on average, Kenya has lost a Nissan matatu-load of people every two days for at least the last decade and a half.

In the face of such appalling statistics, it is nothing short of outrageous that the NTSA considers a reduction of 4 percent in the number of pedestrians who have lost their lives on the roads as “drastic”. Though overall deaths were down by a slightly higher 5.8 percent, it speaks to the low expectations the Authority has of itself that the numbers it is celebrating do not even come close its own rather modest target of reducing traffic fatalities by 12 percent.

By comparison, Norway, which has significantly more cars on its roads had just a tenth of Kenya’s average fatalities per 100,000.

The widely trumpeted but almost always short-lived measures that have been taken by the government to address the issue over the last ten years -such the famous “Michuki rules”, the banning of night buses, enforcement of speed limits, introduction of random breathalyzer tests- have barely budged the average annual number of deaths which still hovers stubbornly around the 3000 mark. By contrast Sweden, which has the world’s safest roads managed to slash in half the number of traffic deaths between 2000 and 2014.

What are the Swedes doing right?

Unlike Kenya’s knee-jerk approach, where reactionary legal measures are quickly announced in the aftermath of a particularly horrific crash, with little research, forethought or long-term planning, and just as quickly forgotten, the Swedes have adopted a more systemic, evidence-based method. Unlike their Kenyan counterparts, the Swedish Transport Administration does not believe that deaths and injuries on roads are an inevitable cost of having a functional road network. “We simply do not accept any deaths or injuries on our roads,” says Hans Berg told The Economist in 2014. Matts-Åke Belin, a traffic safety strategist with the same agency in an interview with CityLab calls it a “civil rights thing”, saying that rather than trying to get people to adapt to the traffic system, the Swedes are trying to “create a system for the humans”.

It may only make the news when crashes either involve large numbers of people or a prominent person is killed, but on average, Kenya has lost a Nissan matatu-load of people every two days for at least the last decade and a half.

This focus on building “a system for the humans” is the central pillar of Vision Zero, the radical policy that since 1997, has governed the nation’s approach to transportation. It is even written into their laws. In the same year, the Swedish Parliament passed the Road Traffic Safety Bill which declared that, “the responsibility for every death or loss of health in the road transport system rests with the person responsible for the design of that system”.

Think about that for a minute. Road accidents are not the fault of drunk or crazy drivers, of careless pedestrians or stupid cyclists. Instead, as Dinesh Mohan notes, the Swedes put the blame on “the engineers who build and maintain the road and the police department that manages traffic on that road. Not primarily on the people who use the road because it has been demonstrated that road user behaviour is conditioned by the system design and how it is managed.”

Vision Zero seeks to not just reduce, but to completely eliminate deaths and serious injuries on the roads. But it does so, not primarily on the back of enforcement of punitive legislation as is the preferred approach in Kenya. “We are going much more for engineering than enforcement,” says Belin. “If we can create a system where people are safe, why shouldn’t we? Why should we put the whole responsibility on the individual road user, when we know they will talk on their phones, they will do lots of things that we might not be happy about? So let’s try to build a more human-friendly system instead. And we have the knowledge to do that.”

Enforcement of traffic rules is an important element but rather than merely bullying road users into compliance, the Swedes are building their system around the road users. Safety is not something that is added to the road system; it is an essential component of the system itself. As one analysis of the policy puts it: “Road users are responsible for following the rules for using the system set by the designers. If the users fail to obey the rules … or they obey and injuries occur nonetheless, the system designers must take steps to avoid people being killed or seriously injured.” The road system is thus built in the knowledge that people will break the rules and is structured to both minimize the opportunity for wrongdoing and to mitigate the harm that can result.

Matts-Åke Belin, a traffic safety strategist with the same agency in an interview with CityLab calls it a “civil rights thing”, saying that rather than trying to get people to adapt to the traffic system, the Swedes are trying to “create a system for the humans”.

In Kenya, the approach is diametrically opposite. While the NTSA acknowledges that 80 percent of road crashes are caused by human error, and blames everything from drunk drivers to jaywalking pedestrians, it rarely discusses the design of our road transport systems, the behaviour it incentivizes and how such errors are mitigated beyond arresting people and increasing fines.

Take the two crashes referenced at the beginning of this tale. Both happened at notorious “black spots”, one at Salgaa and the other at Kabati. Murang’a County Commissioner John Elung’ata says of Kabati, where the Governor died, that “motorists lose control whenever it rains”. The 14-kilometre stretch between Salgaa and Sachangwan along the Nakuru-Eldoret highway has been the scene of multiple horrific accidents involving trucks. Yet in 2015, then NTSA Chairman, Lee Kinyanjui, whose agency blamed the crashes on “ignorant drivers” could only promise that “over and above fining those freewheeling, we will be recommending an immediate revocation of their licences and this should go to all the drivers. Reckless driving on our roads will no longer be there.” In these cases, administrators seem to have either resigned themselves to the inevitability of crashes or limited their responses to punishment. There was not talk of redesigning the road to eliminate the “black spot”. Instead Kinyanjui promised to “construct lorry park with a capacity of 200 vehicles where the NTSA officers will be checking lorries”.

But one could perhaps cut Kinyanjui a little slack. While the NTSA can only advise the national government on such design changes and mostly appears to confine itself to patrolling roads to catch errant drivers or chasing down jay-walking pedestrians, STA actually owns, constructs, operates and maintains all state roads in Sweden.

Obviously, a road system is more than just the state of the road and transport authorities have to coordinate with a wide array of government agencies, non-governmental organizations and road users. That system includes all factors that have a bearing on behaviour on the road. As such, the commitment to safety cannot be simply a matter for one body, but rather a national, even cultural commitment. As Belin says, “Sweden has a long tradition of working with safety. So Vision Zero is also based on a historical context.” It is, after all, the home of Volvo. Kenya, on the other hand, has historically had a rather tenuous relationship with safety and a huge appetite for risk. From our politics to security to our hospitals, being Kenyan is like a constant dicing with death. A national obsession with safety is definitely a bonus. However, even without one, Kenya can make better infrastructural decisions that would reduce the risk of injury and death.

The road system is thus built in the knowledge that people will break the rules and is structured to both minimize the opportunity for wrongdoing and to mitigate the harm that can result.

Take the Thika Superhighway, on which Governor Gakuru died, as an example. The road which rumbles through populated areas is Kenya’s most dangerous road for pedestrians. In 2014, the Senate committee on transport and infrastructure found that over 200 pedestrians had died since the road was inaugurated two years prior. Nearly 300 had been injured. That works out to about 5 people killed or injured every week. The difference between Thika Superhighway and, say, the UK’s M40 is not that Kenyans are congenitally poor drivers and law breakers and the British are not. In fact, the M40 does have its fair share of pile ups. But the reason you do not find pedestrians dashing across it and buses stopping on it is mostly that such problems have been engineered out. People don’t run across it because it is not located where they would need to. We obviously cannot physically move our Superhighway but we can ask questions about how and where our roads are built and about the systems governing the behaviour on them.

We can also ask about emergency responses, or rather, the lack of them. And about the safety of guard rails and whether there are better alternatives. Road accidents, even when they do happen, need not result in grievous injury or death. Why weren’t systems for rescuing trapped people and getting them emergency care factored into the design of the road? How can Kenya fix this? And what rules for other existing and future highways?

Perhaps nowhere would such approach be beneficial than in addressing the safety problems posed by Kenya’s public transport system. According to the WHO, in Kenya “buses and matatus are the vehicles most frequently involved in fatal crashes and passenger in these vehicles account for 38 percent of total road deaths.” Although the 2015 study found that matatus only caused about a third as many accidents as cars and utility vehicles considering that matatus make up only about 5 percent of the about 2 million vehicles on our roads, the fact that they cause around 15 percent of accidents indicates a big problem.

The study found that “Kenyan drivers cause crashes largely because of behavioural and attitudinal problems” and that these problems were more acute in drivers of Public Service Vehicles. “While matatu drivers are viewed as crooks, they regard other drivers as amateurs and always try to show them that they have superior driving skills.”

However, adopting the Swedish approach, one would not just settle for blaming the drivers, as the study, the NTSA and pretty much all of Kenya does. Considering the ecosystem they operate in, the ridiculous and seemingly suicidal behaviour of matatu drivers seems rational, reasonable even.

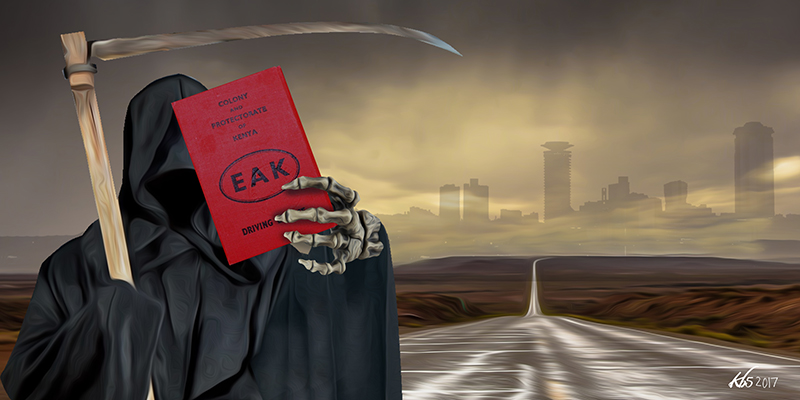

Kenya, on the other hand, has historically had a rather tenuous relationship with safety and a huge appetite for risk. From our politics to security to our hospitals, being Kenyan is like a constant dicing with death.

The late Donella Meadows, in Thinking in Systems – A Primer described a system as “a set of things—people, cells, molecules, or whatever—interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time,” and invited us to consider the implications of the idea that any system, to a large extent, causes its own behavior. Consider the Kenyan public transport system, which is privately owned and dominated by matatus.

Most matatu crews are not salaried. They basically have a deal with the matatu owner where they deliver an agreed sum every day and get to share what is left over. This means that their daily income is directly tied to how many people they carry and how many trips they make. At the same time, as this Africa Uncensored investigation reveals, most traffic policemen on the road are there, not to enforce the rules, but to extort bribes, matatus being a favourite target. In fact, during vetting by the National Police Service Commission last year, many traffic officers were unable to explain the source of their wealth and the many mobile transactions they seemed to be making. Given that it has been reported that most actually pay their superiors for the privilege of being deployed on the roads, it does not take a rocket scientist to figure out where they were sending the money.

The rub of this is that matatu drivers have big incentives to stop anywhere to pick up passengers and to make as many trips as possible, even when this means driving like madmen. The police, on the other hand, have little incentive to enforce the law. And given that many powerful government officials and senior police officers own matatus, there is little incentive to fix the problem.

Looked at from this perspective, it is clear that the problem is less incompetent drivers with an attitude problem, but rather the perverse system of incentives which generates the behaviour. Thus the solutions proposed, such as retraining and recertifying drivers, will have little effect. As US philosopher Robert Pirsig, wrote in his book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, “if a factory is torn down but the rationality which produced it is left standing, then that rationality will simply produce another factory.” Similarly, retraining drivers without changing the underlying system will resolve nothing.

Considering the ecosystem they operate in, the ridiculous and seemingly suicidal behaviour of matatu drivers seems rational, reasonable even.

Changing the system would require the NTSA to confront more powerful forces than lowly matatu crews, but is the true measure of the government’s commitment to dealing with the carnage matatu’s wreak on the road. However, it is not just where matatus are concerned that Kenya could benefit from a serious retooling. Rather than shooting from the hip when confronted with speeding or drinking drivers, the country would do well to adopt a research and evidence-based approach which looks at the problem in all its facets. For example, if, as one study found, “mandatory seat belt use laws and beer taxes may be more effective at reducing drunk driving fatalities than policies aimed at general deterrence,” should Kenya be focusing on those?

An important aspect of ensuring roads are safe is ensuring the road system caters for the needs of all its users, not just a few of them. That requires understanding how the roads are actually used. According to the World Bank’s Kenya State of the Cities Baseline Survey released in March 2014, half the labour force and three-quarters of students walk to work or to school. Another 43 percent and 19 percent respectively use matatus. Only 3 percent actually drive to work. Yet Kenyan roads treat pedestrian traffic as an afterthought and, as detailed above, the public transport system is in a shambles. This inevitably creates conflicts and, as statistics show, it is passengers and pedestrians who bear the brunt of the violence on our roads. Similarly, as the use of motorcycle-taxis, or bodaboda, has increased, so has the number of fatalities and injuries associated with them.

Concepts such as the Dutch-inspired “shared space”, which does not privilege cars and other motorized transport but rather treats the road as a community asset for the use of all traffic, motorized or otherwise, could help reduce the carnage. Well thought-out policies, including pedestrianizing the CBD, have been successfully adopted in cities like Pontevedra in Spain, which eliminated 53 percent of traffic in the city as a whole and 97 percent at its historical centre. “We inverted the pyramid,” its long serving Mayor, Miguel Lores, says, “leaving the pedestrians above, followed by bicycles and public transport, and with the private car at the bottom.” As a result, the city has not had a single traffic fatality in 6 years.

Understanding behaviour on the roads does not require condoning its unsavoury aspects. Rather, it means Kenya can get to grips with the systemic reasons such behaviour is prevalent and why it is destructive. It means, beyond demonizing road users, the NTSA and other stakeholders within and outside the government consider how they contribute to the problem, and what needs to change in order to either eliminate the incentives for that behaviour or to mitigate its effects.

Concepts such as the Dutch-inspired “shared space”, which does not privilege cars and other motorized transport but rather treats the road as a community asset for the use of all traffic, motorized or otherwise, could help reduce the carnage.

In fact, Kenyan roads are a microcosm of the colonially-inspired hierarchies at work in Kenya and the relative values they place on the time, lives as well as the fortunes of the various classes of Kenyans. At the very top is the political class and those riding on their coat tails, from government officials to the wannabe county potentates for whom nothing is allowed to get in the way of their dash to riches. The tiny middle class is next in line and at the very bottom of the pile are the poor, whose presence on the Kenyan road is barely tolerated despite their vastly superior numbers. When, periodically, their anger spills over in riots and “mass action” they can take over the streets entirely. Like the traffic police, the institutions of accountability simply serve to keep everybody in their proper place. They are there to police the citizens, to clear a path for their betters.

Eliminating traffic deaths and injuries is an achievable goal. But to do it, Kenya must change, not just its roads and its drivers, but itself. The country must revolutionize its approach to the problem and start seeing people as the reason the road system, and indeed the entire rubric of government, exists. In short, like Sweden, it must “create a system for the humans”.