“Elections are the surest way through which the people express their sovereignty. Our Constitution is founded upon the immutable principle of the sovereign will of the people. Therefore, whether it be about numbers, whether it be about laws, whether it be about processes, an election must at the end of the day, be a true reflection of the will of the people, as decreed by the Constitution, through its hallowed principles of transparency, credibility, verifiability, accountability, accuracy and efficiency.” – Supreme Court of the Republic of Kenya, 20th September 2017

The concept of sovereignty derives from the historical political relations between rulers, often in the form of states/governments and citizens. The concept of sovereignty became the central idea of modern political science. The word sovereignty is derived from the Latin word superanus, which connotes supremacy. Sovereignty is in essence about the power to make laws and the ability to rule effectively.

Initially, sovereignty was construed as the supreme power of the state over citizens and subjects, unrestrained by law.[1] Following the doctrine of the Social Contract introduced to the realm of political philosophy by Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and others, the theory evolved to mean that in order to avoid the brutal nature of rule by man, citizens and subjects must delegate their power to a legitimate higher authority, referred to as the ‘Leviathan’ by Thomas Hobbes, to exercise that power on their behalf for the benefit of all.

The sovereign is, therefore, the legitimate supreme body that exercises the monopoly of power on behalf of and for the benefit of all its subjects. As such, sovereign power should be exercised in a responsible manner that considers the well-being of all citizens. This naturally presupposes limits to the excesses of state power through the rule of law, equity and justice. For the sovereign authority to retain its legitimacy, as granted to it by citizens, it must exercise this authority with equanimity.

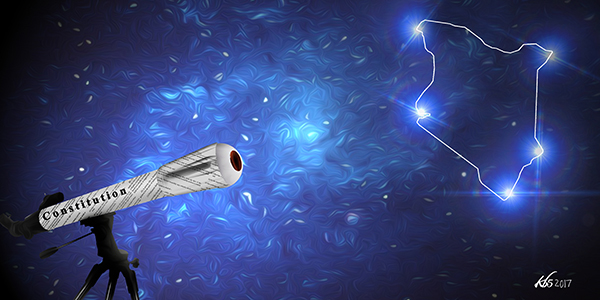

The first Article of the Constitution of Kenya states that sovereign power belongs to the people of Kenya and demands that such sovereignty be exercised by the constitution. It further states that people may exercise their sovereign power either directly or through their democratically elected representatives. Sovereign power is then donated by the people of Kenya to state organs and institutions, such as Parliament, the Executive, the Judiciary, and County Governments and Assemblies, among others.

Contemporary political scholars depart from the absolutist view of sovereignty, which is unconditional and unrestrained by law, as expressed by Jean Bodin, to a holistic approach that views sovereignty as having to be legitimate and derive its authority from the acquiescence of citizens through political processes like elections, policies and public opinion.[2] Hence, the legal sovereign has to act according to the will of the electorate, which is a body of citizens who have the right to vote. Political sovereignty, therefore, implies suffrage, with each individual having one vote, and control of the legislature by the representatives of the people.

The first Article of the Constitution of Kenya states that sovereign power belongs to the people of Kenya and demands that such sovereignty be exercised by the constitution. It further states that people may exercise their sovereign power either directly or through their democratically elected representatives. Sovereign power is then donated by the people of Kenya to state organs and institutions, such as Parliament, the Executive, the Judiciary, and County Governments and Assemblies, among others. Consequently:

“The basis for Sovereignty of the People lies in honouring the precept that when people surrender to the state their right to exclusively govern themselves, in exchange for proper representation in that respect, the government becomes the citizenry’s agent for such purposes. For instance, this right called universal suffrage (one’s right to vote) is exercised by the Kenyan people every five years as per their constitutional entitlement protected by law. The government’s power as a result is not absolute; but more accurately, it is to be executed, as a matter of fact, in such manner as would lead to the necessary accountability of government to the people since it is they that established the state as well as its constituent organs in the first place.”[3]

Kenya’s political and electoral history

Given that sovereignty is exercised through universal suffrage, it follows that the right to suffrage must be respected and elections need to be legitimate. Kenya’s political history is replete with instances of electoral malpractices that served to bastardise regimes that were propagated by electoral processes that were grossly skewed in favour of incumbency. Illegitimate electoral processes were the hallmark of the one-party state under President Daniel arap Moi’s KANU[4] dictatorship.

Despite the fact that future elections in 1992 and 1997 were held by secret ballot, the legacy of Mlolongo entrenched a political culture of electoral fraud and malpractices, including voter bribery and intimidation, alteration of votes in transit and state-sponsored violence in areas that were perceived as hostile to the executive.

The most notorious desecration of electoral democracy during this era was the queue-voting system of 1988 known as ‘Mlolongo’. The decision to conduct primaries by having voters queue behind the image of their favoured candidates set the stage for massive rigging. Voting malpractices had been witnessed in other elections but this decision made it possible to cheat on a scale never witnessed before, given the opportunity it presented for open voter bribery and intimidation to queue behind state-sponsored or regime-friendly candidates.[5]

Despite the fact that future elections in 1992 and 1997 were held by secret ballot, the legacy of Mlolongo entrenched a political culture of electoral fraud and malpractices, including voter bribery and intimidation, alteration of votes in transit and state-sponsored violence in areas that were perceived as hostile to the executive. The violence was often designed to displace ‘hostile’ communities in order to curb voter turnout. Given the broad-based nature of the National Rainbow Coalition that ushered in the regime of President Mwai Kibaki in an anti-KANU/Moi wave that produced a landslide victory for the then opposition, the country was spared large scale electoral fraud and malpractices in 2002.

The 2002 General Election was held in the context of the expiry of Moi’s two-term limit following pre-1992 constitutional amendments that introduced multiparty democracy through the repeal of Section 2 (A) of the independence Constitution, which in turn had been amended in 1982 to render Kenya a de jure one-party state. The political reforms of that era introduced a two-term limit, meaning Moi could only serve a maximum of two terms post-1992. Moi, however, vigorously campaigned for his protégé Uhuru Kenyatta, who faced a united opposition that rallied behind Mwai Kibaki.

In 2007, the ghost of electoral fraud and malpractices returned to haunt the country. Pitting the incumbent Mwai Kibaki, now under the Party of National Unity (PNU), against Raila Odinga of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), the election results, which appeared to reverse an unassailable lead by Raila Odinga, led the country to widespread violence pitting supporters of the two factions against one another and police killing of civilians. The use of private militia to inflict violence was among other factors that led to the functionaries of the two parties and the Commissioner of Police being charged with crimes against humanity before the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The Independent Electoral Review Commission (IREC), chaired by the South African Judge Johann Kriegler, conducted an in-depth investigation into the 2007 Election, and concluded that:

“There was generalised abuse of polling, characterised by widespread bribery, vote buying, intimidation and ballot-stuffing. This was followed by grossly defective data collation, transmission and tallying, and ultimately the electoral process failed for lack of adequate planning, staff selection/training, public relations and dispute resolution. The integrity of the process and the credibility of the results were so gravely impaired by these manifold irregularities and defects that it is irrelevant whether or not there was actual rigging at the national tally centre. The results are irretrievably polluted.”[6]

The Kreigler Commission report informed reforms to the Elections Act and the provisions of the Constitution of Kenya 2010 relating to elections. The Commission of Inquiry into Post- Election Violence (CIPEV), together with the Kriegler Commission, agreed that the flawed electoral process contributed significantly to the 2007-2008 post-election violence. The legal and policy framework governing future elections was an effort to boost credibility and legitimacy of elections in Kenya and to prevent the recurrence of violence. Given Kenya’s chequered political history with regard to elections, specific reforms were made following the recommendations of the Kriegler Commission and other processes to cure particular mischiefs, including the alteration of votes in transit. As such, electronic transmission of results was introduced, with accompanying forms signed and verified by competing political party agents in order to curb electoral irregularities and illegalities.

In this regard, the language of the Constitution of Kenya 2010 and the various amendments to the Elections Act is elaborate, with the words credibility, accountability, verifiability and others qualifying the standards required of elections in Kenya with specific regard to vote tallying, transmission and declaration.

The phraseology of Article 23 of the Constitution of Kenya is a deliberate endeavour to cure the mischiefs identified by the Kriegler Report. It demands that whatever voting method that is used, the system is simple, accurate, verifiable, secure, accountable and transparent.

The phraseology of Article 23 of the Constitution of Kenya is a deliberate endeavour to cure the mischiefs identified by the Kriegler Report. It demands that whatever voting method that is used, the system is simple, accurate, verifiable, secure, accountable and transparent. The framers of the constitution inserted these words to govern elections in Kenya, given the country’s peculiar context and political history with regard to the legitimacy of elections, which are in turn the way in which the people of Kenya exercise their sovereignty. Electoral legitimacy therefore becomes a prerequisite for the genuine exercise of sovereignty. In order for the People of Kenya to exercise their sovereign will through elections, they must be carried out in a manner that is free, fair, credible, transparent, secure, accountable and verifiable. They must be carried out in accordance with the provisions on elections in the Elections Act and the Constitution of Kenya 2010.

Sovereign legitimacy

Political and legal scholars have deliberated upon the doctrine of legitimacy as a prerequisite to the exercise of sovereignty. The following passage from Hugo Grotius’ On the Law of War and Peace expresses the modern perspective of legitimacy in the context of political authority and sovereignty:

“But as there are several Ways of Living, some better than others, and every one may choose which he pleases of all those Sorts; so a People may choose what Form of Government they please: Neither is the Right which the Sovereign has over his Subjects to be measured by this or that Form, of which diverse Men have different Opinions, but by the Extent of the Will of those who conferred it upon him”.[7]

John Locke’s version of social contract theory elevated consent to the main source of the legitimacy of political authority. Legitimacy as a prerequisite to the exercise of sovereignty is captured in the doctrine of popular sovereignty:

“Popular sovereignty, or the sovereignty of the people’s rule, is the principle that the authority of a state and its government is created and sustained by the consent of its people, through their elected representatives (Rule by the People), who are the source of all political power. It is closely associated with social contract philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Popular sovereignty expresses a concept and does not necessarily reflect or describe a political reality. The people have the final say in government decisions.”[8]

Benjamin Franklin expressed the concept when he wrote: “In free governments, the rulers are the servants and the people their superiors and sovereigns“[9]. Popular sovereignty, in its modern sense, is an idea that dates to the social contracts school (mid-17th to mid-18th centuries), represented by Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), John Locke (1632–1704), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), author of The Social Contract, a prominent political work that clearly highlighted the ideals of “general will” and further matured the idea of popular sovereignty. The central tenet is that legitimacy of rule or of law is based on the consent of the governed. Popular sovereignty implies the exercise of power with the consent of the governed. It is a basic tenet of most republics and some monarchies.[10]

Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau were the most influential thinkers of this school, all postulating that individuals choose to enter into a social contract with one another, thus voluntarily giving up some of their natural freedom in return for protection from dangers derived from the freedom of others. Whether men were seen as naturally more prone to violence and rapine (Hobbes) or to cooperation and kindness (Rousseau), the idea that a legitimate social order emerges only when the liberties and duties are equal among citizens binds the social contract thinkers to the concept of popular sovereignty.[11]

Legitimacy and legality of elections in Kenya

Within the ambit of political theory, one can locate ideas of sovereignty having to be legitimate and based on the rule of law in order to compel citizens to obey the sovereign to which they have donated their individual power for the benefit of all. If sovereign power is exercised with disregard for the rule of law, its legitimacy may cease. As such, the sovereign power derives its authority from those governed and exercises its power legitimately, in accordance with the rule of law and not arbitrarily. In the Kenyan context, where the framers of the constitution saw it fit for sovereignty to reside in the People of Kenya, they alluded to a form of popular sovereignty that requires legitimacy, rule of law, public participation and constitutionalism as a central components of state authority.

Form 34 (A) was deliberately provided for in the law to arrest the mischief of votes disappearing in transit through the verification process of agents. Further, there is a context in which the two Houses of Parliament jointly prepared a technological roadmap for conduct of elections and inserted a clear and simple technological process in Section 39(1) (C) of the Elections Act, with the sole aim of ensuring a verifiable transmission and declaration of results system. In the presence of these illegalities and irregularities, it is difficult to establish whether the sovereign will of the People of Kenya was exercised through the ballot on August 8th 2017.

Without the tenets of constitutionalism, rule of law and public participation, the exercise of sovereignty would be illegitimate. Given the current political environment in which the Supreme Court of the Republic of Kenya nullified the August 8th presidential election citing substantial irregularities of such a magnitude as to impugn the integrity of the electoral process and, given that the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), as recently stated by its Chairman Wafula Chebukati, has not made any changes that would render a fresh election credible, will the sovereign will of the people be legitimately exercised through a fresh election on October 26th or any date thereafter without the changes and reforms sought in compliance with the Supreme Court decision?

The Supreme Court impugned the August 8th presidential elections on the basis that they were fraught with so many illegalities and irregularities that so negatively impacted the integrity of the elections that no reasonable tribunal could uphold the election. The most critical and persistent non-compliance with the law was that the IEBC-announced results on the basis of Forms 34B before receiving all Forms 34A.

It was also alleged that the results announced in Forms 34B were different from those displayed on the 1st respondents’ public web portal, contrary to section 39 (1) & (C ) of the Elections Act. The results were not transmitted in the prescribed form, given that results began to stream into the national tallying centre without the mandatory forms 34 (A). Form 34 (A) is the primary document that captures all results from polling station or streams. It is signed by both the presiding officer and agents at the polling station for purposes of verifiability. In the context of Kenya’s electoral history, where votes were often altered in transit, the primacy of this document is critical and not merely a mode of transmission.

Form 34 (A) was deliberately provided for in the law to arrest the mischief of votes disappearing in transit through the verification process of agents. Further, there is a context in which the two Houses of Parliament jointly prepared a technological roadmap for conduct of elections and inserted a clear and simple technological process in Section 39(1) (C) of the Elections Act, with the sole aim of ensuring a verifiable transmission and declaration of results system. In the presence of these illegalities and irregularities, it is difficult to establish whether the sovereign will of the People of Kenya was exercised through the ballot on August 8th 2017.

This is exacerbated by the fact that the Supreme Court drew an adverse inference on the part of the IEBC for failing to provide access to logs and servers to the petitioner (Raila Odinga), concluding that this was a golden opportunity for the IEBC to disprove the allegations of Mr. Odinga with regard to infiltration of the servers and alteration of forms and votes. The Court made an adverse inference on the IEBC, stating that for it to spurn such an opportunity to disprove the petitioners claim of hacking and alteration, IEBC officials themselves interfered with the data or simply refused to accept that it had bungled the whole transmission system and were unable to verify the data.

The Chairman of the IEBC, in a statement on 18th October 2017, less than 10 days before the proposed 26th October election, admitted that under the current conditions, ‘it is difficult to guarantee free, fair and credible elections’. He added that: ‘without critical changes in the Secretariat staff, free, fair and credible elections will surely be compromised’[12] while referring to a deeply divided IEBC.

A day before this statement by Mr. Chebukati, a Commissioner of the IEBC, Roselyne Akombe, fled the country citing fears for her life, stating that the IEBC was under political siege and that: “the commission in its current state can surely not guarantee a credible election“[13]. According to former Commissioner Akombe:

“We need the Commission to be courageous and speak out, that this election as planned cannot meet the basic expectations of a CREDIBLE election. Not when the staff are getting last minute instructions on changes in technology and electronic transmission of results. Not when in parts of the country, the training of presiding officers is being rushed for fear of attacks from protestors. Not when Commissioners and staff are intimidated by political actors and protestors and fear for their lives. Not when senior Secretariat staff and Commissioners are serving partisan political interests. Not when the Commission is saddled with endless legal cases in the courts, and losing most of them. Not when legal advice is skewed to fit partisan political interests. The Commission in its current state can surely not guarantee a credible election on 26 October 2017. I do not want to be party to such a mockery to electoral integrity.”[14]

These revelations from both the Chairman of the IEBC and a senior Commissioner cast doubt on the Commission’s ability to carry out a legitimate election on October 26th or any other date before making necessary changes to correct the reasons for nullification identified by the Supreme Court on 1st September 2017. Any election without these changes and under the prevailing political circumstances would not meet the test of credibility, transparency, accuracy and verifiability. Such an election would not legitimately reflect the sovereign will of the People of Kenya.

Environment of fear and intimidation

Following the annulment of the August 8th presidential election by the Supreme Court, state security agencies clamped down heavily on citizens demanding credible elections through peaceful protests. In Nairobi, the police brutalised citizens in Mathare, Kibera, Baba Dogo, Dandora, Korogocho, Karoabangi and Kawangware. In Kisumu, the use of live bullets against civilians has been documented following protests against the declaration of Uhuru Kenyatta as the duly elected President by the IEBC on August 9th, a declaration that was later nullified by the Supreme Court. According to Kisumu County Governor Anyang’ Nyong’o: “171 cases of police brutality were reported, six of them rape; seven deaths were confirmed while several people were reported missing.”[15]

The prevailing climate of civil protest and excessive retaliation by state security agencies, including use of live bullets, does not provide an enabling environment for elections free of violence and intimidation. Public participation, freedom of assembly, association and the right to picket and to demonstrate are enshrined in the constitution. An environment in which fundamental political rights are suppressed in the conduct of an electoral process, which is supposed to express the sovereign will of the people, renders that process illegitimate.

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch published a report on 16th October 2017 titled Kill Those Criminals: Security Forces’ Violations in Kenya’s August 2017 Elections documenting excessive use of force by the police, and in some cases other security agents, against protesters and residents in some of Nairobi’s opposition strongholds after the elections. According to the report:

“At least 23 people appear to have been shot dead by police, three beaten to death, and three died of asphyxiation from tear gas and pepper spray, two trampled to death, and two of physical and psychological trauma. Residents and human rights activists told researchers of another 17 cases of deaths resulting from police actions in informal settlements in Nairobi. Witnesses and human rights activists told researchers of at least four bodies that they said they saw being removed by police in Kibera,; the identities of the victims and where they are currently located are unknown. Dozens of others suffered gunshot wounds and severe injuries due to police beatings.”[16]

Further:

“Police used excessive force against protesters, firing teargas in residential areas or inside houses, shooting in the air but also directly into the crowd and carrying out violent and abusive house to house operations, beating and shooting residents.”[17]

This environment of police brutality and intimidation by state security agencies persists and looms large over the proposed date for the fresh election, October 26th 2017. There is heavy and menacing police presence in opposition strongholds seemingly deployed to supress peaceful protestors on, before and after October 26th. Given the trend witnessed in the aftermath of August 8th election, repeated police brutality is likely to follow on, before and after October 26th. The Inspector General of Police issued a statement on 20th October 2017, warning of stern consequences for protestors in the course of the fresh election date. This comes in the wake of the arrests and detention of County Assembly Members in Mombasa and Kisumu for their alleged role in mobilising protestors ahead of October 26th.

Is this environment of fear, brutality and intimidation conducive to the conducting of a free, fair, transparent and credible election? Can the People of Kenya exercise their sovereign will through elections in such an environment? The framers of the Constitution envisaged that citizens should be able to take part in free and fair elections without fear of violence and intimidation. Indeed, violence and intimidation are key elements in Kenya’s electoral jurisprudence as grounds for invalidation of parliamentary and civic elections. In George Gitiba Njenga v Mutunga Mutungi & another [2017] eKLR, the Political Parties Dispute Tribunal restated the requirement for free and fair elections in the context of absence of violence and intimidation as one of the general principles undergirding Kenya’s electoral processes:

“For an election exercise to be said to have been free and fair, according to Article 81 of the Constitution of Kenya, 2010, the following conditions must be met. They include allowing voting through secret balloting, freedom from violence, intimidation and improper influence or corruption, elections being conducted transparently by an independent body and administered in an impartial, neutral, efficient, accurate and accountable manner.”[18]

The prevailing climate of civil protest and excessive retaliation by state security agencies, including use of live bullets, does not provide an enabling environment for elections free of violence and intimidation. Public participation, freedom of assembly, association and the right to picket and to demonstrate are enshrined in the constitution. An environment in which fundamental political rights are suppressed in the conduct of an electoral process, which is supposed to express the sovereign will of the people, renders that process illegitimate.

Conclusion

It is the author’s view that the sovereign will of the people cannot be legitimately expressed in an environment of state terror against civilians. Further, the imposition of an electoral process without the acquiescence of a broad cross-section of the electorate, including the candidate in whose favour the Supreme Court ruled in nullifying the August 8th 2017 election, negates the doctrine of popular sovereignty as it imposes coercive power without consent.

Without this participation, consent to the date and significant remedies for the illegalities and irregularities of the electoral process of August 8th and the proposed election to be carried out on October 26th provide no remedy for the lack of electoral accountability which the Supreme Court sought to enforce in its full decision read on 20th September 2017. Any election in the prevailing political environment, including where the Chairperson of the constitutionally-mandated electoral body, together with a Commissioner, have publicly expressed their reservations about the October 26th poll, cannot be credible and would not legitimately convey the sovereign will of the People of Kenya.

By James Gondi LL.M

The author is a rule of law analyst. His research areas include human rights law, international humanitarian law and transitional justice.

[1] Dunning, A ‘Jean Bodin on Sovereignty’ Political Science Quarterly Vol 11 No 1 1986

[2] Patil, Jaiwantaro Mahesh ‘ Sovereignty’ Nayanvar Chavan Law College, Nanded (Mahashatra), India

[3] Ojwang J.B “Constitutional Reform In Kenya: Basic Constitutional Issues and Concepts” 2001 quoted in Kaindo & Maina “Sovereignty of the People and Parliamentary Supremacy” 2014

[4] Kenya Africa National Union, independence political party.

[5] Mugo, Waweru “How the ‘Mlolongo’ System Doomed Polls” The Standard Newspaper 20th November 2013

[6] Report of the Independent Review Commission on the General Elections held in Kenya on 27th December 2007, Page X of the Executive Summary available at: http://kenyalaw.org/kl/fileadmin/CommissionReports/Report-of-the-Independent-Review-Commission-on-the-General-Elections-held-in-Kenya-on-27th-December-2007.pdf

[7] Grotius, Hugo On the Law of War and Peace in Political Legitimacy Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy April 2017

[8] Duke, George Strong Popular Sovereignty and Constitutional Legitimacy European Journal of Political Theory 2017

[9] Popular Sovereignty and the Consent of the Governed Published by the Bill of Rights Institute, Documents of Freedom- History, Government and Economics through Primary Sources

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Wafula Chebukati: I Can’t Guarantee Credible Poll on October 26 Daily Nation 18th October 2017 available at http://www.nation.co.ke/news/Wafula-Chebukati-on-repeat-presidential-election/1056-4145232-oyj67sz/index.html

[13] Resignation Statement of IEBC Commissioner Dr Roselyne Akombe published in Business Today available at https://businesstoday.co.ke/dr-roselyn-akombe-resigns-heres-full-statement/

[14] Ibid

[15] Standard Newspaper ‘Kisumu, the Lakeside City Bears Scars of Constant Police Brutality’

Read more at: https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001254087/kisumu-the-lakeside-city-bears-scars-of-constant-police-brutality 10th September 2017

[16] “Kill Those Criminals” Security Forces Violations in Kenya’s August 2017 Elections. Amnesty International Report at Page 14, 16 October 2017, Index number: AFR 32/7249/201 Available at https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr32/7249/2017/en/

[17] Ibid

[18] Republic of Kenya Political Parties Dispute Tribunal Complaint Number 234 of 2017