In recent years, there has been a push for gender gap reporting as part of measures to promote gender equality. The World Economic Forum first published its Global Gender Gap Index in 2006, to compare gender gaps in economic opportunities, education, health and political participation, and has published regular reports since then.

In Kenya, Equileap first published a report on gender equality in Kenya in 2019, evaluating gender balance in leadership and workforce, equal compensation and work-life balance, policy and commitment, transparency and accountability in publicly listed companies.

While some companies have made progress in some areas, the gender pay gap—the difference in average earnings between men and women—persists. Globally and locally, women are still paid much less than men.

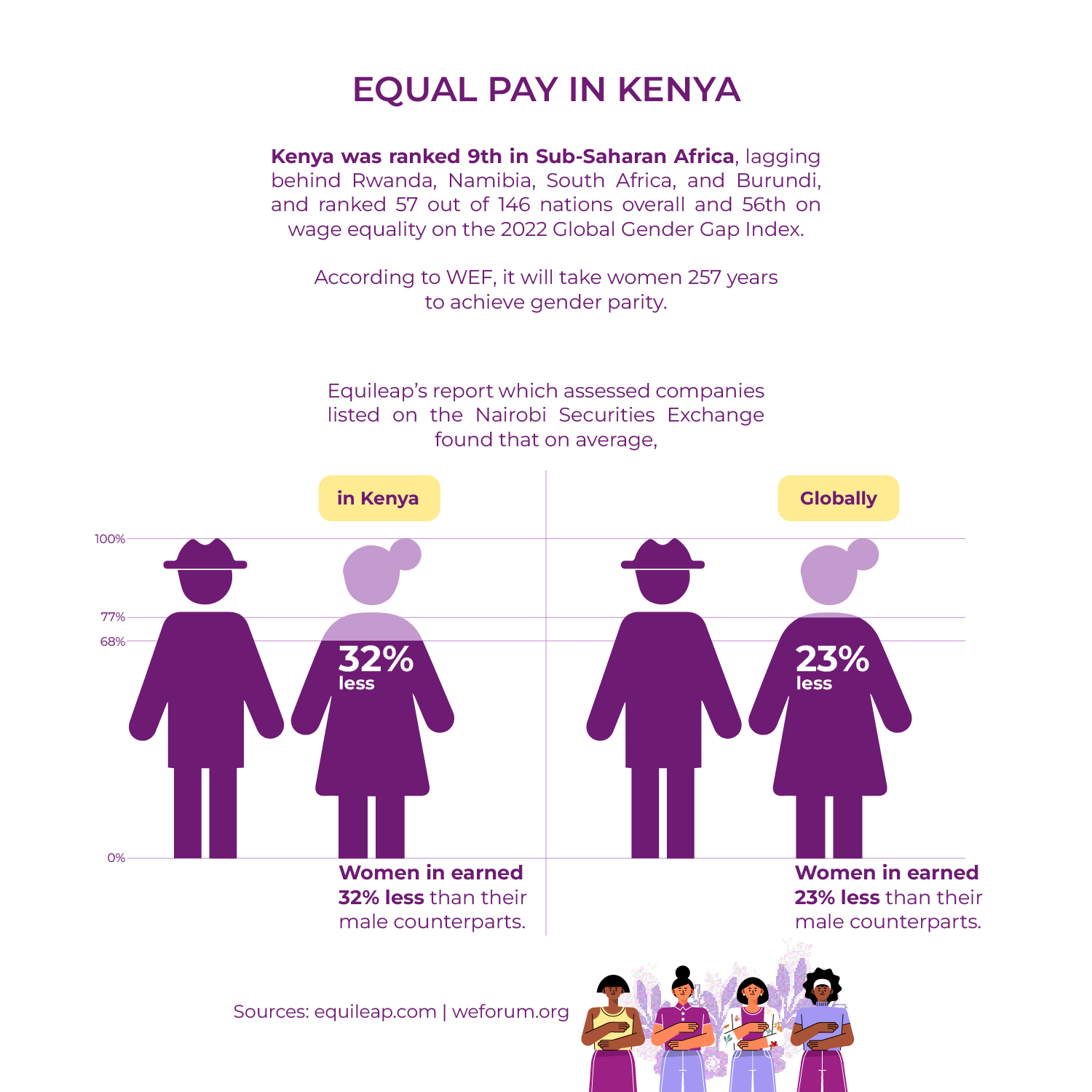

Equileap’s 2019 report, which assessed companies listed on the Nairobi Securities Exchange, found that, on average, women in Kenya earned 32 per cent less than their male counterparts. This was less than the global average. Globally, women earned 23 per cent less than their male counterparts.

Subsequently, Kenya was ranked ninth in Sub-Saharan Africa, lagging behind Rwanda, Namibia, South Africa, and Burundi, and ranked 57 out of 146 nations overall, and 56th on wage equality on the 2022 Global Gender Gap Index published by the World Economic Forum (WEF). According to the WEF, it will take women 257 years to achieve gender parity.

This year as the world marks the International Women’s Day, whose theme is “Embrace Equity”, the Africa Women Journalism Project (AWJP) is launching a gender pay gap campaign to challenge Kenyan companies to produce gender pay gap reports. Such reports are crucial to monitoring the efforts that companies are making to have a diverse workforce, and be inclusive and equitable.

The gender pay gap, says the International Labour Organization, is a barrier to economic growth and has a significant impact on other key sustainable development goals such as reducing poverty and ending gender inequality. The campaign will focus on all sectors where women are under-represented and their work is under-valued.

The principle of gender pay equity is provided for in Kenya’s Employment Act, 2007, which requires an employer to pay their employees equal pay for work of equal value. Further, Articles 27 and 41 of the Constitution also enshrine gender pay equity by providing for gender equality and, specifically freedom from discrimination, the right to fair remuneration and the right to fair labour practices. The principle of gender pay equity is also covered in Goal 5, on gender equality, of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals ratified and adopted by Kenya and other member states of the United Nations in 2015. Kenya has also ratified the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which prohibits discrimination based on sex and provides for equal remuneration in Convention 111 and 100 respectively. In particular, CEDAW provides that each member state will promote and ensure the principle of equal remuneration for men and women for work of equal value.

Women are paid less over the course of their careers and subsequently save less for their retirement, subjecting them and their dependents to lifelong poverty.

These commitments notwithstanding, Kenyan women still earn less than men, with far-reaching consequences. Closing the gender pay gap in the Kenyan workforce matters because it is a glaring injustice as it violates women’s rights, devalues their work, reduces their spending power, and makes their position unequal to men from the household to the national level.

The gender pay gap is not just about pay discrimination. It arises because of the inequalities women face in access to work, progression and rewards. The European Commission states that “around 24 per cent of the gender pay gap is related to the overrepresentation of women in relatively low-paying sectors such as care, health and education. Highly feminised jobs tend to be systemically undervalued.” Moreover, thanks to the glass ceiling, men dominate higher-paying jobs.

The European Commission also argues that women have more work hours per week than men, but they spend more hours on unpaid work, which may affect women’s career choices.

As a result, women are paid less over the course of their careers and subsequently save less for their retirement, subjecting them and their dependents to lifelong poverty. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these consequences.

According to Action Aid, the gap contributes to financial insecurity and poverty among women, limits women’s life choices and leaves them more vulnerable to violence and other forms of discrimination and exploitation, since they are more likely to be financially dependent on men or other family members. This dependency can limit a woman’s ability to leave a violent partner.

Case for narrowing and closing the gap

During an Equal Pay International Coalition pledging event at the 2018 United Nations General Assembly in New York, Angel Gurría who was the OECD Secretary General at the time said, “Gender pay gaps are not only unfair for those who suffer them, but they are also detrimental to our economies. If you do not have equal pay productivity suffers, competitiveness suffers and the economy at large suffers.”

Further, the Council of Foreign Relations, a non-governmental organisation in the United States, through its Women and Foreign Policy programme, analysed how to grow economies through gender parity. Their research indicated that with gender parity in the workforce, GDP growth in sub-Saharan Africa would be US$721 billion by 2025.

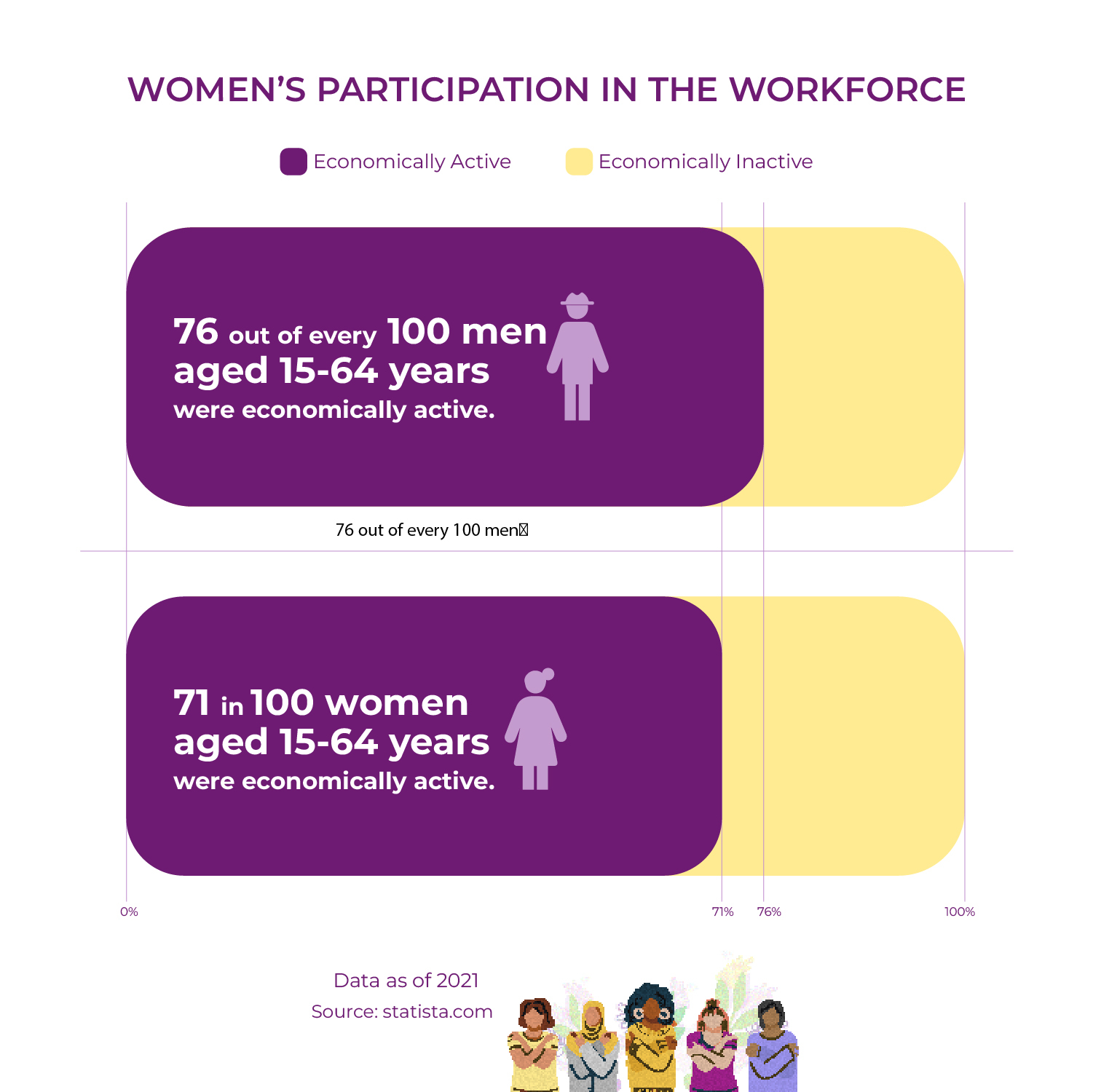

In Kenya, this could translate to a 12 per cent (US$16 billion) increase in GDP if women’s participation in the workforce matched the best country in the region in terms of gender parity, and 22 per cent (US$28 billion) if women’s participation in the Kenyan workforce was fully equal to men’s. The participation rate as of 2021, which is the current available data, was at 75.6 per cent for men. This means that nearly 76 in every 100 men aged 15-64 years were economically active. Among women, the rate was lower, at 71 per cent. Not only is women’s participation in the workforce lower, they also grapple with pay imbalances.

Unfair compensation

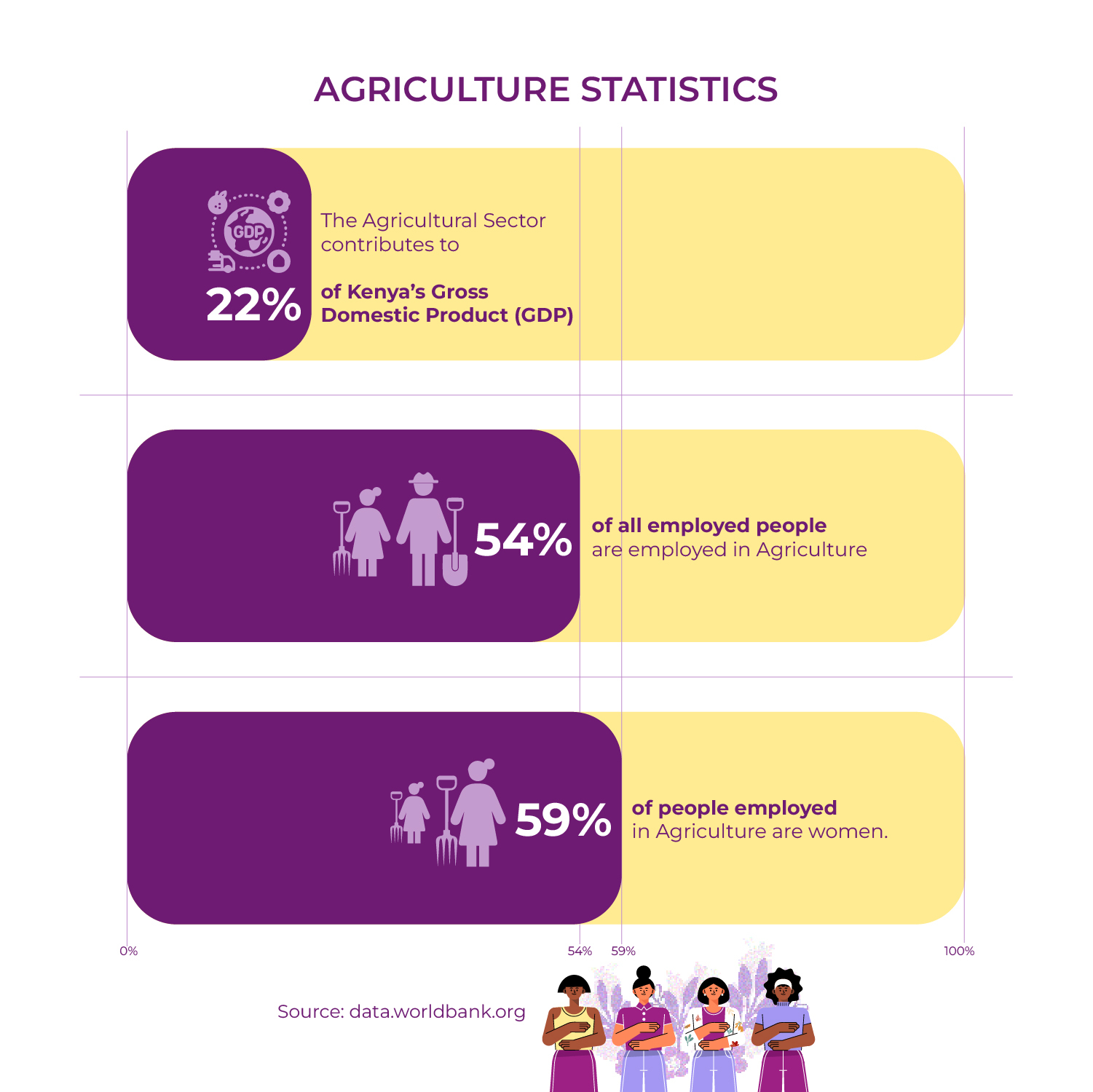

Among them are women in the agricultural sector, which contributes 22 per cent of Kenya’s gross domestic product (GDP) and employs 54 per cent of the economically active population, according to the World Bank. Of all the workers employed in agriculture, 59 per cent are women.

As such, the sector is critical to gender pay equity because women account for nearly 60 per cent of the agricultural workforce, and one of the primary reasons for this is men’s rural-urban migration in search of paid employment in towns and cities, either in their own country or abroad.

Even in cases where men remain in rural areas, women are responsible for the production of food crops for domestic consumption and sale, as well as the rearing of animals. They are also the primary keepers of crop variety and production knowledge. Despite this, they are not fairly compensated for their work because they do not own the land. In Kenya, only 25 per cent of women own agricultural land compared to 34 per cent of men. Of the women who own land, only 3 per cent are sole owners in contrast with 26 per cent of men.

Moreover, with a high inflation rate of 9 per cent in January 2023 and higher unemployment rates—186,402 jobs were lost in 2020 according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics—women, who accounted for 61.9 per cent of the jobs lost during the pandemic, are more vulnerable to exploitation. Moreover, the economic realities make it harder for them to negotiate fair wages. Lack of pay transparency through measures such as gender pay gap reporting also hinders the ability to negotiate.

Even in cases where men remain in rural areas, women are responsible for the production of food crops for domestic consumption and sale, as well as the rearing of animals.

Nowhere are the disparities more evident than in the tea sector, the second top foreign exchange earner for Kenya after horticulture, contributing 23 per cent of total foreign exchange earnings and two per cent of the agricultural gross domestic product (GDP). Annually, the country produces over 450 million kilogrammes of tea of which 22 per cent is exported, earning the country KSh120 billion and making it one of the commodities that play a key role in the economy. In 2021, tea brought in KSh130.9 billion in revenue.

Tea production in Kenya is divided into two clearly differentiated sectors: the big plantations and the smallholder farmers. Over 60 per cent of production takes place on small-scale farms in Kenya, while the rest takes place in large plantations owned by companies like James Finlay and Williamson Tea.

A study of gender roles in smallholder tea production in Kenya found that women are more likely to be engaged in labour-intensive tasks in tea production—including leaf plucking and transporting plucked leaves—but are excluded from capacity-building events such as producer trainings.

Brewing inequality

Tina Makokha (not her real name) is one such woman who has worked at the James Finlay farm in Kericho for 10 years. She started out on a wage of Sh190 per day as a tea picker, and despite receiving four certificates of merit for being an exceptional employee, she earns Sh689 per day for nine hours of work per day, six days a week. After tea-picking was mechanised, women were moved from that role and given jobs in weeding, sorting the tea before transportation and clearing the cuttings left on the tea bed by the plucking machines, which are operated by men.

For the last three months, Tina has worked without pay. She is afflicted with work-related illness as a result of the agrochemicals used on the tea, but when she visits the company’s dispensary, she says the doctors downplay her complaints of chest congestion and chronic coughing. She injured her back while packing tea four months ago, and the company refused to pay her medical bills until the union threatened to sue on her behalf. The company, she claims, reluctantly subsidised her medical treatment at the company’s health centre and informed her that any specialised treatment she needed would be her responsibility.

When she refused to sign a liability waiver, the company withheld her pay she said. They’ve also stopped providing her with subsidised medical care at the dispensary.

“I’m not sure why they wanted me to sign a document that I didn’t understand. I have had to forego treatment for my back because they have withdrawn their support.

“I cannot afford the treatment because it is very expensive,” she says during the interview, which is punctuated by bouts of coughing.

She claims that she and other workers have complained to management about their working conditions, but their demands have been ignored. Tina has had to take out loans to pay for her medical treatment. At one point, she was admitted to hospital for two weeks without receiving any treatment as she did not have the money to pay.

The health centre’s services are insufficient, forcing workers like Tina to use their meagre resources to seek treatment elsewhere.

The company has established schools for its employees and those living in the vicinity of the extensive tea plantations. However, this is yet another example of the disconnect between reality and the directors’ reporting to shareholders. Tea workers like Tina must pay a hefty fee — between KSh1,000 and KSh1,200 per month—for their children to attend the company-provided school.

Tina’s daughter is still at home after scoring 328 points in the 2022 KCPE exam. Tina is unable to pay her secondary school fees because she spent all of her savings on medical treatment.

The health centre’s services are insufficient, forcing workers like Tina to use their meagre resources to seek treatment elsewhere.

“The company has built a few schools. But these are not free. The company deducts between Sh1,000 and 1,200 every month if your child attends the school. None of us has ever gotten the scholarships that the company offers as these are usually granted to the children of the managers,” she says.

Tina’s life is a snapshot of the negative effects of the gender pay gap, not just on women, but also on communities and the economy at large.

Gender pay gap disclosure

The UK, where the parent company of James Finlay Kenya is based, historically had one of the widest gender pay gaps in Europe, where for every pound men earned women earned 80 pence (for every Sh154 men earned women earned Sh122). That’s why in 2017, the UK government introduced mandatory gender pay gap reporting to narrow and eventually eliminate the pay disparity between men and women. This compelled private sector firms and public sector organisations with 250 or more employees in England, Scotland and Wales to report and publish their gender pay gap information using the gender pay gap service on their snapshot date, which is the 30th of March for most public authority employers and the 5th of April for private and other public authority employers.

The report includes figures on the percentage of men and women in each hourly pay quarter, the average gender pay gap using hourly pay, the mean gender pay gap using the hourly wage, the percentage of men and women receiving bonus pay and the median gender pay gap using bonus pay. Although discretionary, they may also publish a supporting narrative and an action plan to help explain their gender pay gap.

“The company has built a few schools. But these are not free. The company deducts between Sh1,000 and 1,200 every month if your child attends the school.”

The policy aims to make employers publicly accountable for their gender pay gaps and impel them to explain why they exist while using the gender pay gap reporting tool to inform decisions about pay structures and broader diversity and inclusion. Four years after the policy was adopted, research from the London School of Economics indicated the legislation had narrowed the earning gap between men and women by 19 per cent.

In line with the mandatory reporting requirement, Finlays (James Finlay Kenya’s parent company in the UK) files a gender pay gap report in its home country. The latest data indicate that the mean hourly pay for men is 3.9 per cent higher than that for women; median hourly pay for men is 10.6 per cent higher than that for women; mean bonus pay for women is 69.7 per cent higher than that for men; median bonus pay for women is 296.3 per cent higher than that for men and 32.8 per cent of male employees received a bonus, while 22.4 per cent of female employees received a bonus.

What about Kenya?

But although the subsidiary company that employs thousands of workers in Kenya, James Finlay (Kenya) Ltd, is registered in the UK, it is not obliged to file similar reports because the employees are not based in the UK. Even though Kenya has committed to gender pay equity through laws such as the Constitution and the Employment Act, and international conventions like CEDAW and SDGs, there are no specific guidelines to compel local companies to file gender pay gap reports.

Williamson Tea is another top tea exporter whose parent company is in the UK. The UK shareholder company does not file gender pay gap reports because it does not employ enough staff there to fall within the UK’s mandatory reporting threshold. However, the Equileap report on gender equality in Kenya, which evaluated measures including equal pay in companies listed in the Nairobi Securities Exchange, gave Williamson Tea a gender equality score of 3 per cent and ranked it at position 56 out of 60 companies. Other listed agricultural companies were also ranked: Limuru Tea (34 per cent at position 19), Sasini (16 per cent at position 42), Kakuzi (15 per cent at position 44), Eaagads (13 per cent at position 51) and Kapchorua Tea Kenya (3 per cent at position 57).

In contrast, the top three companies—Standard Chartered Kenya, WPP Scan Group and Safaricom—scored 63 per cent for offering a living wage, gender-balanced leadership and workforce, and workplace policies that promote gender equality, respectively.

The Equileap report, which used publicly available information such as the companies’ annual reports, CSR reports and websites, however, noted a lack of transparency in compensation. None of the 60 companies disclosed gender-segregated pay information, and 37 of the companies (62 per cent) did not publish information on the gender composition of their workforce.

In the UK, where Finlays and Williamson Tea have parent companies or controlling shareholders, the Equileap report revealed a gender equality score of 37 per cent versus Kenya’s 26 per cent. In 2021, the company wage bill for James Finlay Ltd was US$12.8 million (KSh1.9 billion) and it employed an average of 82 people, implying an average wage of US$156,000 (KSh 2.3 billion) for its UK head office. In contrast, the 2020 accounts for James Finlay Kenya showed that the average wage for its 6,667 employees was £2,513 (KSh372,828.68).

In 2020, the workforce of James Finlay (Kenya) Ltd was composed of management and administration, which accounted for 446 and 393 workers respectively, and sales and production, which accounted for 5,828 workers (87 per cent of their workforce). Given the structure of the tea sector in Kenya, most of these workers are likely women picking or packing tea in the fields and factories. Moreover, the 6,667 workforce for James Finlay Kenya far outstrips the numbers employed by the UK head office and manufacturing plants.

The Africa Women Journalism Project asked Finlays the mean and median hourly pay for men and women working at James Finlay Kenya and whether the company had data internally to produce a gender pay gap report for the Kenyan workforce. AWJP also asked Finlays if gender pay gap reports have helped focus attention on companies closing the gap and whether they would commit to publishing such a report voluntarily in Kenya, the location of their biggest workforce, in the next 12 months as part of a progressive corporate move.

In the UK report, Finlays Group HR Director Tamie Hutchins had said that the company was “committed to closing the gender pay gap, to equal pay and to fostering a transparent and fair working environment that rewards employees based on their performance and contribution to the success of our business.”

Given the structure of the tea sector in Kenya, most of these workers are likely women picking or packing tea in the fields and factories.

Further, Ms Hutchins said, “Finlays is committed to being an employer that demonstrates opportunity, fairness and equality and the work we are doing to reduce our UK Gender Pay Gap is essential to us achieving this goal. We are pleased to see continued improvements in our mean gender pay gap, especially in view of the impact Covid has had on working women in the UK, which has been reflected in the increase in the UK pay gap in 2021.”

In an email response to AWJP’s questions, Ms Hutchins said: “While we currently only publish gender pay gap data for our UK business, we do have plans in our new sustainability strategy, which runs to 2030, to extend the measure of gender pay gap across the whole of Finlays.”

In 2021, the company also launched the Finlays Women in Business Forum which Ms Hutchins said was “helping our female employees find their voice and supporting us in driving through the changes they tell us are needed.” Ms Hutchins was quoted in the 2021 report saying that the company’s focus in 2022 would be “to better understanding (sic) our pay quartile splits and the impact these are having on our pay gap and on opportunities for women working within our business.”

However, in response to AWJP’s question on whether there are any Kenyans on the forum and whether it discusses issues to do with women in the Kenyan workforce, Ms Hutchins said that the Women in Business Network relates to Finlays’ UK and US businesses and that James Finlay Kenya has a “Women in Leadership Programme” which “sees women in both senior and junior management undertaking a nine-month leadership development programme facilitated by Kenya Institute of Management.”

“The programme’s objective is to equip women with leadership skills and provide a network where safe discussion on work-related practices and personal empowerment can take place,” she said, adding that 28 senior managers and 23 junior managers have graduated from the programme, while 25 women are currently enrolled.

However, for women in their Kenyan sales and production workforce like Tina, such programmes in a company that has committed to fairness, equality and closing the gender pay gap, sound like a far-fetched dream.

Tina told us that her wages barely cater for living expenses and despite receiving certificates of merit for exemplary performance, she neither feels rewarded nor sees any promotions in the pipeline.

While the workers did not previously have a way to air their grievances and were also afraid of management, Tina said that the company recently began instituting a channel for the workers to air their grievances.

While Ms Hutchins did not respond to the questions on mean and median hourly pay in Kenya, Tina said she earns Sh689 per day for nine hours a day, six days a week, which she said is the standard pay for tea pickers and packers at the company.

In the absence of mandatory or voluntary gender gap reports, women face not just discrimination and injustice but vulnerability to exploitation and abuse. Recently, the BBC revealed tens of cases of sexual exploitation and sexual harassment of women working in tea farms in Kericho, including at James Finlay Kenya and Unilever Tea (which was sold to Lipton Teas). In response, Finlays said it had suspended the manager implicated in the documentary, reported the matter to the police and launched investigations into sexual violence in the company.

AWJP asked Finlays to comment on whether empowering women in their Kenyan workforce through gender pay gap reporting may help avoid these kinds of issues in the future. Finlays did not give a direct answer. Finlays Group HR Director Tamie Hutchins said the company was deeply shocked by the allegations and has policies in place to prevent abuse of any kind.

Tina said she earns Sh689 per day for nine hours a day, six days a week, which she said is the standard pay for tea pickers and packers at the company.

“As we are still formulating our approach, we are not in a position to provide specific details at the current time, but I assure you it is an area that we are working to address,” said Ms Hutchins in response to the question on whether gender pay gap reporting could help prevent cases of abuse highlighted in the BBC documentary.

Tina, who works as a tea packer at James Finlay Kenya, said that in dealing with issues of the pay gap the company would need to start with the way workers are hired and treated. She said that the contractors the company brought in to source for workers are exploitative; they pay between KSh250 and Sh300 per day, while workers employed directly by the company are paid KSh689 per day.

“While it is difficult to comment on the claims of an individual who has chosen to remain anonymous, to allow us to investigate fully, we encourage Tina to raise her concerns through the available channels, which include an anonymous whistleblowing line monitored by head office in London. I assure her that all concerns raised will be investigated, and appropriate support will be provided where needed,” James Finlay’s Tamie Hutchins stated.

“The health and safety and welfare of everyone connected to our business are of paramount importance to James Finlay Kenya. We have a well-established health and safety programme which includes staff training programmes, processes to ensure that we maintain a safe working environment for all workers, and a robust monitoring and improvement process which identifies opportunities for further development. We have a dedicated team of 22 individuals who oversee welfare at James Finlay Kenya, and a wide range of support is available to all on site.”

After the BBC documentary, Finlays said it had terminated its agreement with contracting company Sislo Holdings (whose owner was accused of sexual exploitation), and offered direct employment to the 300 workers who had been contracted by that company. She added that an approachable and respectful management, as well as an effective redress mechanism to protect women from sexual exploitation during recruitment and pathways to promotions for exceptional work would go a long way in closing the gender pay gap.

Not just Finlays

Williamson Tea is another major tea company and exporter in Kenya with significant links to the UK.

Although a listed company on the Nairobi Stock Exchange, it is ultimately majority owned by the Magor family in the UK. Its listing in Nairobi also means it has to publish its annual financial statements, which show that in 2021/22, the company’s total wage bill for its 1,105-strong workforce was KSh488,007,002, an average of KSh441,635. In contrast, the total paid to its three executive directors that year was KSh49,112,000, an average of KSh16,370,666. Moreover, its entire board of directors is male.

As a Kenyan company, Williamson Tea Kenya is not obliged to produce a gender pay gap report, but we challenged the company to provide some data and commit to doing so for our campaign.

The company had not responded to our questions by the time of publication.

Requiring local reporting on gender equality and gender pay gap, just like in the UK, where mandatory reporting has led to transparency and sustained action towards closing the gap, could also boost efforts to reduce the gap.

The National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC) wrote a gender equality and inclusion guidebook for the private sector in 2014 to “entrench principles of equality and inclusion in business practices in Kenya.” In it, the NGEC recommends that private companies monitor gender equality and inclusion indicators such as total workforce numbers, annual numbers recruited and promoted, and contract terms by sex, as well as the pay gap between the sexes and employee satisfaction surveys. The NGEC also recommends that companies collect data on work-life balance and career development to track access to career progression opportunities through training and promotions. It recommends that companies develop and implement policies on gender equality and inclusion, and collect and publicly disclose data and reports on the status and progress made in the implementation of the recommended principles.

However, none of these guidelines are mandatory, so companies are not compelled to act to reduce the gender pay gap and other forms of gender inequality and as such, even though Kenya has ratified various conventions on equal pay, without mandatory reporting criteria, employers are not held to account to provide information on gender matrices.

A report published in 2021 by the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at Kings College London recommends actions countries can take to build systems that bridge the gender pay gap in tandem with policies on parental leave, minimum wage and pay transparency as part of a broader strategy to address workplace gender inequality.

The report recommends not just laws, but also guidelines from the government as well as monitoring and enforcement of compliance. In the report, the researchers recommend that employers be made accountable to government agencies and publish transparent gender pay gap reports.

“Gender pay gap reports should be included in a company’s annual report and sent to shareholders, investors and other interested parties. Employers should also, crucially, be accountable down to their employees, whether to a group of employee representatives, trade unions, or to the organisation as a whole.”

Even though Kenya has ratified various conventions on equal pay, without mandatory reporting criteria, employers are not held to account to provide information on gender matrices.

Beyond publishing pay gap reports, the institute recommends that companies provide action plans with clear, measurable and time-bound goals to narrow the gap, and that sanctions be applied to those who do not comply with laws on gender equality. Moreover, because small and medium-size businesses account for majority of employers, policies to address the gender pay gap should not be limited to large employers alone. In addition, government and employers should collect data on the difficulties faced by women based on social factors that could keep them from workforce participation and career progression.

For employers, the institute recommends that they advertise all jobs as flexible where possible, address blockages to women’s employment and progression, work to increase pay transparency and end outsourcing of low-paid workers where possible.

Enforcing gender pay reporting through the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection and the Ministry of Public Service, Gender and Affirmative Action can help narrow the gap by improving compliance and the quality of reporting by ensuring the reporting processes are followed by actionable, custom-fit and executable plans to address existing pay gaps.

–

This article was produced as part of the Financial Reporting Skills for Gender Reporting Fellowship with support from the Africa Women Journalism Project in partnership with Finance Uncovered and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).