There are two approaches to exercising your imperial ambitions over others. One is simply to invade their territory with armed force and subjugate them. The other is to bring some of their own leaders, or potential leaders, onto your side with inducements or threats, and so enforce your rule indirectly. The big historical empires usually did both.

Britain, for example, famously ruled India by securing the allegiance of that vast country’s five hundred princely states, step by step. Some were defeated in battle, some were taken over with mutually beneficial trade – beneficial for the rulers, that is. Others were led to accept, even embrace, British dominion through inducements and bribery. London established its rule over the whole subcontinent and beyond even though its fighting men and civilian administrators were always vastly outnumbered by the locals. For every Brit in the “Raj”, there were always well over a thousand Indians. The numbers were only a little more balanced in Kenya, where just 23,000 European settlers dominated a realm of over five million Africans.

Of course, indigenous resistance forced the empires’ retreat and proved the imperial model to be unsustainable. But the Europeans’ belief in their own superiority, and that the rest of the world could and should be manipulated to their own advantage, proved harder to dismantle and may have as many adherents now as it had at the empires’ height.

Conservation is just one area in which colonial control remains embedded, certainly in Kenya and in much of Africa and beyond. About 20 per cent of Kenya’s land is in Protected Areas (PAs) (of which about 9 per cent is state land and the remainder is private) and they are overwhelmingly run by the descendants of white colonists and subsidised with enormous amounts of money provided by conservation NGOs and governments from northern Europe and the USA. Those which make a profit do so off tourism from non-Africans, often rich ones who can afford a minimum $1,000 per person per night for luxury holidays, with only a few crumbs from the table ever dropping into the hands of indigenous Africans. For comparison, the average salary for a Kenyan working in the hospitality industry or as a wildlife ranger is less than US$5,000 a year.

In the last decades of the twentieth century, some well-meaning conservationists finally began to note the criticism that they had been seizing indigenous and other peoples’ lands without consent, or even any pretense at consultation. They began to realise that the traditional concept of African Protected Areas, as zones which exclude local people – including those who had been living there for many generations – was in urgent need of reform. Even those with no interest in changing still recognised the pressing need for rebranding: conservationists began to realise that they risked losing public support unless they claimed they were working in partnership with the locals, even when they weren’t.

At about the same time, some white farmers in Kenya began to think that their land – originally given to them to produce food for the colony – could make them more money if they turned it into Protected Areas and start hosting paying visitors. Overall costs would be small: the properties had been stolen from Africans and handed to the settlers without charge, the houses and other facilities had been built by underpaid locals, and a bevy of servants (now called “staff”) could readily be drawn from the nearby population. On the other side of the ledger, overseas guests would be happy to fork out the same fortunes they were used to paying for luxury accommodation in the Global North, or even more as an experience of “wild Africa” was highly prized and marketable. The enduring white fantasy of sub-Saharan Africa as an untouched Garden of Eden, populated largely by exotic megafauna, and popularised in literature and film throughout the twentieth century, could be a money spinner.

Conservationists began to realise that they risked losing public support unless they claimed they were working in partnership with the locals, even when they weren’t.

The realisation that conservation dollars might be ripe for the taking seems to have first occurred in the 1980s in Lewa Downs, an old cattle ranch north of Mt Kenya which had been given to the Craig family by the colonial government sixty years before. The Craigs had already leased part of it to an Englishwoman, Anna Merz, who trucked in rhinos from all over Kenya, keeping the animals in – and Africans out – with armed guards and electric fences. Ian Craig, a former big game hunter, decided to landscape the whole ranch around wildlife tourism, bringing in more rhinos and other iconic species that visitors would pay to see.

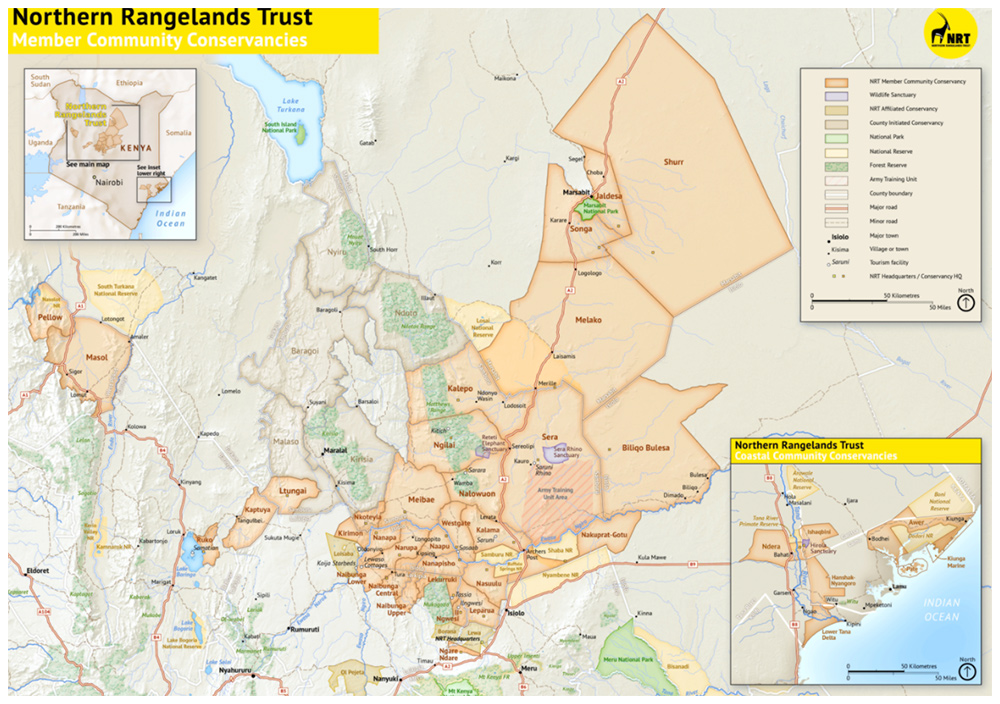

The former ranch at Lewa has become the driving force for a new wave of Protected Areas, known as “conservancies”, which are springing up throughout Kenya and beyond. Most are promoted by a rather opaque local NGO, the Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT), established by Craig himself in 2004, (although the NRT gives a different account of its genesis, saying the first suggestion came from Francis Ole Kaparo, former speaker of Kenya’s National Assembly) which in turn is heavily supported by the biggest and richest conservation organisation in the U.S., The Nature Conservancy (TNC) (more on that below).

There are now over three dozen conservancies, covering huge swathes of Kenya, totalling about 11 per cent of the country (6.3 million hectares at the last count). They have overtaken national parks in size and are often cited as the vanguard for a conservation reformation which has discarded the old “fortress” model and replaced it with “community-based conservation”, supposedly set up under the control and even ownership of local people. They have become the standard rebuff to critics who point out that wildlife protection remains essentially colonial, run by and for non-Africans.

The former ranch at Lewa has become the driving force for a new wave of Protected Areas, known as “conservancies”, which are springing up throughout Kenya and beyond.

As so often with projects in the Global South – and many in the Global North for that matter – peeling away the propaganda can uncover hidden depths. To start with an aside, though one which resonates deeply with many Kenyans, Lewa’s links with the old colonial power remain celebrated. Prince William spent part of his “gap year” there in 2000 and was boyfriend to Ian Craig’s daughter. The royal heir remains a frequent guest, he proposed to the future queen in one of its tourist “camps”, and they named one of the guest tables at their wedding dinner after it. Ian Craig was awarded an Order of the British Empire by the Queen in 2016. British government ministers, including future Prime Minister Boris Johnson, have also visited. If you can pull the right strings, it’s easy to drop by. The largest British army base in Africa is less than fifty kilometres away, just a few minutes’ helicopter hop.

Land use in northern Kenya is key to understanding how the conservancies have been established and the problems they are throwing up. As the cool, fertile slopes of Mt Kenya slope down to a lower plateau which extends 250 miles north to the Ethiopian border, the country becomes hotter, arid, and less conducive to settled farming. This is part of the traditional domain of several peoples who have lived from mobile pastoralism for many hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years. They herd sheep, goats, camels and, most famously for the Maasai and Samburu, cattle. At first sight, it seems like an arduous way to live in a landscape which supports little visible vegetation. But in practise, like so many “traditional” lifestyles, it is actually highly – and sophisticatedly – attuned to the environment. It depends on a high degree of mobility, with herds walking large distances to take advantage of regional precipitation, changing seasons, and the appearance or disappearance of surface water. Both herds and herders know where they are heading, and why, applying a complex understanding of the terrain and weather consolidated over many generations.

The landscape gives sustenance to livestock and people, and is then left to regenerate until another herd arrives to take its share; it’s also the stage on which these peoples have their genesis and where their identity is forged. With many different peoples (Rendille, Borana, Gabbra, Turkana, Pokot, etc., as well as Samburu and Maasai) using the same terrain, there is a perpetual balancing of neighbourship and shared values against the potential for friction, often over competition for grazing and water. National frontiers, drawn with rulers on maps by the colonial powers, are largely invisible and substantially porous, with troubled Ethiopia to the north and war-torn Somalia in the east.

British dominion over this part of Africa had been established for less than thirty years when the end of the “Raj” in 1947 India clearly signalled the sun was setting over the empire as a whole. After several years of armed struggle, which was met with brutal suppression by the colonials, Kenya finally saw the inevitable final lowering of the Union Jack in 1963. The British left a few thousand settlers behind, and many of their core beliefs. One was the mistrust, even hostility and disdain, with which all national governments view peoples who favour a mobile approach to life over a fixed abode: nomads, of course, are always very difficult to tax and control.

The enduring white fantasy of sub-Saharan Africa as an untouched Garden of Eden populated largely by exotic megafauna could be a money spinner.

Old-fashioned conservationists invariably see herders as parasites on the environment, draining it of sustenance and giving nothing back. This is in spite of the increasing scientific realisation that the ecosystems of the great East African grass plains are actually the creation of grazing animals, which enhance rather than diminish the country. Peoples who live from mobile herding, like others who eat mainly from their hunting and gathering, enjoy a way of life which in reality improves rather than reduces biodiversity, and which has sustained a huge proportion of Africa’s population for millennia. The upper end of estimates count no less than one quarter of the population of all Africa as dependent on herding.

But the colonials saw things differently. Immersed in anthropological prejudice which placed settled agriculturalists at the apex of human evolution, they had long been in favour of reducing, and even ending, pastoralism – and subsistence hunting – altogether. The same bias was inherited by the newly independent Kenyan government which was largely dominated by those from the Gikuyu ethnic group, traditionally farmers who produced Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta. The herders have faced discrimination for a long time.

The British Crown had originally “given” the so-called “White Highlands”, the higher, cooler, malaria-free centre of the country, to white settlers in the 1920s, particularly to World War I veterans like Ian Craig’s grandfather. When the new landholders started erecting fences, the surrounding herders were forced to adapt, avoiding some areas altogether and grazing others only covertly, often risking arrest or armed violence when they cut fences. However, nomadic peoples, whether herders or hunters, are generally far more agile and versatile than their static neighbours, so they adapted and survived and, by and large, are still there.

After Kenyan independence, one way of continuing to try and press herders into the settled mainstream was to recognise their communal ownership, but only over restricted parts of their grazing. This was shoehorned into existing land legislation really written for peoples who stayed put. The herders, at least some of them, were awarded “Group Ranches”, in which specific kith and kin became the owners of limited areas. To represent their title to the authorities, they had to establish committees, habitually through their councils of elders—most African pastoral peoples have a codified hierarchy in age sets, where important decisions are traditionally referred to older folk.

That is an outline of the complex background of competition for land when white farmers decided to move into wildlife tourism. It was easy enough for them to embrace Craig’s conservancy model for their own farms, but when it came to getting land which was under African communal ownership, the Group Ranches owned by the pastoralists, more inventive means had to be deployed to press the case for turning productive grazing into private tourist parks.

Sometimes this might have involved genuine consultation with, and consent by, the community; in other cases, it didn’t. The elders, or sometimes just a few individuals picked up by NRT and driven to its meetings, would be asked to agree terms on a 30-year lease which gave away designated parts of their land to an “investor”, a company which would build visitor accommodation geared around wildlife viewing. In exchange, the African landowners would be given a few, largely menial, paid jobs in and around the “lodge” or luxury camp, but they would also have to provide security around its perimeter and clear any necessary roads and infrastructure, all without any further payment. The Group Ranch would receive a small fee for each night a tourist stayed, unless the visitor were an associate or family member of the investor, in which case there would be no payment. What this amounted to was that the herders would get a few jobs and very little money in exchange for giving away a substantial part of their land for a generation. The herders had no experience in securing their own legal advice, and the contracts made no reference to Group Ranch members having access to any audited figures to check whether or not they were being correctly remunerated.

When it came to getting land which was under African communal ownership, more inventive means had to be deployed to press the case for turning productive grazing into private tourist parks.

Such agreements are not made public or translated into any local language. They would never pass scrutiny for fairness, or even legality, which is probably why copies of the contracts were not made available to some communities, and why some remain confidential to the investor decades after they were signed (Requests to be shown copies of contracts were ignored but I have nevertheless read some from confidential sources.) Moreover, when the lease ends, some are liable to be renewed automatically for another thirty years on the same terms.

“Agreements” like these are barely disguised land grabs. The herders lose part of their land for little return, with the investor taking possession to build high-end accommodation. The tourist business can then truck in some big animals, and start raking in handsome profits from rich tourists whose expectations of being waited on by bedecked, colourful African “warriors” and women are fulfilled. The waiters and cleaners are of course the rightful landowners.

In this way, self-sufficient, independent, and resilient herders have been turned into a servant sector entirely dependent on an industry which is, in turn, dependent on the whims of tourist fashion (and which has proved particularly unsustainable because of travel curtailments arising from the COVID-19 pandemic).

Another way the NRT has begun to erode pastoralism has been to establish its grip over the regional economy. It has formed a business, buying the livestock of favoured herders (but not that of critics) and selling it on to the food industry. NRT can presumably afford the financial risk because any losses can be offset by tourist profits and conservation grants from wealthy backers like The Nature Conservancy which are in turn subsidised by Western governments. Such economic domination has undermined regional markets and elevated NRT into a key economic driver of northern Kenya – all supposedly for the benefit of the local population.

Old-fashioned conservationists invariably see herders as parasites on the environment, draining it of sustenance and giving nothing back.

NRT can get away with all this partly because the leases are between a particular investor and a Group Ranch: NRT claims its role is merely as hands-off adviser, and denies liability for any unfairness as it’s not itself a formal party to any of the contracts. It advises the investor certainly, but any claim that it can give advice which is in the best interest of the herders at the same time is clearly not true.

Its annual reports don’t show any audited figures, as NGOs in Kenya are not legally required to produce independently verified accounts in the way they are in Europe or the USA. Requests to see them are rebuffed or ignored; how it sources its funds is vague. It can, in other words, make whatever unsupported claims it likes: the possibilities for creative accounting, to say the least, seem great.

NRT Conservancies

It’s understandable that knowledgeable Kenyans are suspicious of such an opaque NGO gaining effective control over much of northern Kenya and directly impacting the lives of millions of Africans. When a white Kenyan with close links to the former colonial master’s head of state is pulling the strings, such concerns are likely to be amplified, even more so when TNC’s involvement is considered – especially given some conservationists’ stated desire to stop all meat eating (aside from chicken) throughout the continent, for supposedly environmental reasons!

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) should be better known outside the USA, if only because it is the wealthiest conservation NGO in the world, with an annual income of over a billion dollars. Its headquarters are less than six kilometres from the White House in Washington, and it was headed by investment banker Mark Tercek until 2019. He used to be a managing director and partner at Goldman Sachs until the financial collapse of 2008 when his bank’s role in the subprime mortgage crisis exploded. Together with Lehman Brothers, Goldman Sachs was a major player in the mess which led to job losses for nine million Americans. This was the time that Tercek left banking for conservation, though the switch may not have involved much transformation in his worldview, or been too onerous a sacrifice for that matter: there’s little reason to think he started flying economy class, and his basic TNC salary in 2015 was $765,000. Tercek left TNC in 2019 after a sexual harassment probe into the organisation’s leadership.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) should be better known outside the USA, if only because it is the wealthiest conservation NGO in the world, with an annual income of over a billion dollars.

It’s easy to see why rich Americans getting control of pastoralists’ land in Kenya, via a local NGO with intimate ties to an old colonial élite which still keeps its army on site, is not wholeheartedly welcomed when herders debate in the shade of their thorn trees. Not being given sight of the contracts they are told they once agreed to naturally raises anxiety. There are a few young men who benefit from the jobs, and who understandably might find these developments more agreeable, but opposition remains high. It can be expressed quietly, with those herders who dislike NRT keeping their voices muted for fear that the authorities are listening out for hostile opinion which they think is seditious. Critics have been threatened, and conservationists who question NRT can find career paths shut off.

The British army is there in force with various objectives. It’s obviously found a useful training ground, but the official reasons are to combat terrorism, support peacekeeping and humanitarian aid, and also to help rangers “protect elephants from poachers”. It’s true that many British taxpayers might well support their army protecting elephants, but it still raises uncomfortable questions about the merging of the roles of soldiers, police, and wildlife rangers – especially given that some of the latter are private militias employed by rich white landowners to guard their very expensive properties and wealthy tourists. The minimum price to stay a few days in one luxurious conservancy, Ol Jogi, just thirty kilometres from the army base, is over $34,000. The conservancy has nevertheless received money from a British charity, Save the Rhino, with some of the funds going to ranger training.

What this amounted to was that the herders would get a few jobs and very little money in exchange for giving away a substantial part of their land for a generation.

Concerns are growing over how valuable this land might be aside from its tourist potential. Northern Kenya was always important geopolitically in the slicing and dicing of Africa. It was a cushion between Britain and its colonial rivals, France and Italy, and it remains a buffer between mainly Christian Kenya and war-torn Somalia, the launch pad for violent incursions by al-Shabab militants. These have been going on for years and can meet with sympathy in Muslim parts of Kenya. There is wealth under the ground too – fossil fuels, minerals, and aquifers. All stand to be more easily and profitably exploited were local African landowners to be undermined or removed. After all, Protected Areas in other parts of Africa are often leased out to oil, gas, minerals or diamond companies. It’s possible that getting rid of people from conservation zones is as much about future profits as it is about the 19th century northern European and American belief which elevates divine Nature above sinning humankind.

Even a cursory comparison between maps of mining applications and the conservancies indicates that there could be mineral wealth under at least nine of them (Kalepo, Meibae, Nannapa, Narupa, Naapu, Naibunga Lower, Naibunga Central, Sera, and Biliqo Bulesa), which could affect Samburu, Turkana, Maasai, and Borana. All have, or have had, mining concessions inside their boundaries.

Whatever the reasons behind the growth of the conservancy model, at first sight it’s a win-win for conservationists. They can claim the communities are equal partners, when of course they’re not; yet more of the country can be fenced off into Protected Areas for profit; and the assault on mobile pastoralism – which has long been a key refrain in conservationists’ myopic and ultimately destructive vision of “nature” without humans (except them) – can be fortified.

It’s clever, but as well as its reliance on unsustainable tourism, it embodies another key flaw which may eventually prove its undoing: it doesn’t reckon with the profound relationship many herders have with how they live with and from their animals. They have weathered droughts and conflicts over numerous generations and pastoralists know their way of life is supremely sustainable. Conservancies don’t take into account their resilience and toughness; herders don’t like being pushed around and are prepared to cut fences and risk violence when necessary to protect their livestock and future.

A cursory comparison between maps of mining applications and the conservancies indicates that there could be mineral wealth under at least nine of them.

Real solutions, benefiting both people and the environment, demand discarding deep-seated prejudice, which is always the primary obstacle to real change. The stranglehold of wealthy “landowners” must be loosened. Both conservationists and the government should recognise the importance of nomadic pastoralists as valued stewards of the country’s ecosystems, and stop trying to finish with them. They should approach the herders with respect, offering resources only when asked for, which should be passed into the control of locals represented by their own spokespersons. Of course such a new approach would bring complications, especially with growing competition for resources. However, things are complicated now, and they are marching in the wrong direction.

Unless things change, it seems likely that pastoralists will reoccupy their grazing lands, by force if necessary, and so bring to an end the reign of Protected Areas altogether. Many pastoralists are now seeing that there’s less harassment where there’s less tourism. There are already protest killings, where wild animals are slaughtered, not for tusks, horns, meat, or even because they are a danger to livestock or people, but as retaliation against the land grabs which have dogged these Africans since Europeans first turned up and told them to settle down, get “civilised”, and accept their place in the divine and established order – as landless workers and servants.

–

I am grateful to Dr Mordecai Ogada for leading me to the problem of the conservancies through his book, The Big Conservation Lie, Mbaria & Ogada, 2016, and for commenting on this article.