I first visited Nigeria in 2009, and one of the first things that struck me as we drove around in Lagos was how festive everyone looked. It was an ordinary weekday, and people were doing ordinary things – selling wares by the roadside, navigating traffic, and just going about their day. But there was something striking about how they looked, and then it hit me – they were wearing what we in East Africa call kitenge or “African fabric”.

I had never seen this in everyday life – to me, kitenge was Sunday best, exclusively worn to church or to weddings, and in fact, often only by women of a certain age. Growing up in middle-class Nairobi, you certainly couldn’t catch me dead in kitenge in my teenage years, or more accurately, as soon as I had the power to resist what my mother insisted dressing me up in. It wasn’t cool. We would make fun of kids at Sunday school whose parents would dress them up in matching kitenges; our aesthetic was very much influenced by 1990s African-American hip-hop – FILA sneakers, denim dungarees (overalls), Nike and FUBU, and midriff-baring crop tops that our parents would disparagingly call “tumbo cuts”.

***

In the 1980s and 1990s, many African countries were pressurised to adopt structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) imposed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which were supposed to fix structural problems in African economies – remove foreign exchange controls, privatise state corporations, and liberalise trade.

These adjustments – sometimes grudgingly implemented by African governments, sometimes enthusiastically so – led to massive job cuts, crumbling public services and a stagnated formal sector. The social fall-out from these programmes was devastating to many communities, especially in the wake of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

But the liberalised trade also provided opportunities for a different kind of route to prosperity in Africa. This was made possible by the expansion of three airlines: Ethiopian Airlines, Kenya Airways and South African Airways. Before the airline revolution in Africa, it could take days to transit from one city to another, and very frequently one had to transit through Europe – for example, Douala to Abidjan had to be connected via Paris.

However, these three airlines made for a very different kind of Africa. Via ET, KQ and SAA, one could move much more easily around the continent and trade with each other, creating what we will call the “kitenge route”.

Perhaps analogous to the silk route through Asia and Europe, the kitenge route was an ordinary businessperson sourcing shea butter from Ghana, or Ankara fabric from Nigeria, and selling it at an open-air market in Kampala; or hundreds of artisanal curio traders getting their artefacts from Kenya and Tanzania and selling them at glitzy malls in Johannesburg.

Along with the airline revolution came satellite television, and primarily South Africa-based Multichoice/ DSTV. Although the absolute figure of DSTV subscribers in Africa is small – just over 10 million households, more than half of which are in South Africa – its impact on the continent’s aesthetic has been outsized.

Perhaps analogous to the silk route through Asia and Europe, the kitenge route was an ordinary businessperson sourcing shea butter from Ghana, or Ankara fabric from Nigeria, and selling it at an open-air market in Kampala; or hundreds of artisanal curio traders getting their artefacts from Kenya and Tanzania and selling them at glitzy malls in Johannesburg.

The explosion of urban African music in the past two decades has been driven by many forces, among them demographic change, globalisation and fast-growing cities, but DSTV’s Channel O was one of the first to create a space for urban music on the continent. Private radio and television stations were also sprouting all over the continent, sourcing music and films from fellow African countries. Platforms like YouTube made art travel even more seamlessly.

For a generation of young Africans who had grown up in the “lost decades” of the 1980s and 1990s, witnessing social decay and economic hardship all around them, the early 21st century was a time of possibility, even if the political reversals were many and economic promises yet to be fulfilled. Education expanded but so did unemployment; SAPs didn’t fix their country’s economic troubles, multiparty democracy didn’t quite deliver either, but at least they had this.

With that – and in later years, accelerated by social media – young urban Africans were starting to get their cues on what was “cool” from icons as diverse as Mafikizolo, P-Square and T.I.D. They got their fashion tips from Nollywood stars like Omotola J. Ekeinde and Genevieve Nnaji, and shared these ideas online on places like Pintrest, Tumblr, and Instagram.

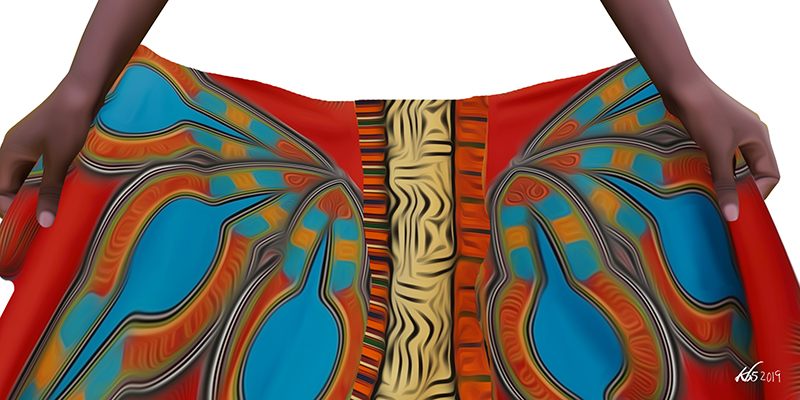

With that, a distinctly “African” aesthetic was created, drawing on different influences all over the continent, unapologetically mixed-and-matched, and melded together into a recognisable yet paradoxically vague “African” identity. You don’t quite know what it is, but you recognise it when you see it in a full Nigerian agbada or gele all the way in Nairobi, fused into an Ankara top-and-jeans combo, or all the way minimised into strips of kitenge fabric on the collar or cuffs of an otherwise “formal” shirt.

As second-hand clothing (called mitumba in Kenya) flooded African markets in this context of liberalised trade, having your own tailored outfit was increasingly a status symbol – leading to a whole demographic of young, self-taught designers and tailors who had picked up their skills from the Internet and from teaching each other. In many places, the previous generation of tailors had largely faded into obscurity from the onslaught of SAPs and mitumba.

Mancini Migwi is one such designer who has found her niche in producing African print designs. “My mother had several kitenge outfits, but my appreciation and love for Afro prints came later in life,” she tells me. “I’m a self-taught artist; I learned to design and sew from watching videos online. Pintrest is my style bible; I draw heavily from what I see people sharing there.”

As second-hand clothing (called mitumba in Kenya) flooded African markets in this context of liberalised trade, having your own tailored outfit was increasingly a status symbol – leading to a whole demographic of young, self-taught designers and tailors who had picked up their skills from the Internet and from teaching each other.

One of Migwi’s clients is the musician Dan Aceda, who is friends with the television journalist Larry Madowo. For a while, Madowo hosted The Trend, a Friday night variety show which was at one time one of Kenya’s highest-rated television programme. Madowo would wear a different design every week, and Aceda was performing in high-profile music events like the Koroga Festival and Blankets and Wine. Aceda tells me that he was competing with his friend to see who could “unleash the best jacket”. It was a contest between friends that was playing out in front of millions of people – and subtly influencing what young people considered cool.

And for Rwandan designer Matthew “Tayo” Rugamba, the link between his rise as a designer, social media and an online buzz is even more obvious. The founder and creative director of bespoke menswear designer label House of Tayo, Rugamba was in college in Portland, Oregon in the United States when he put up a post on Tumblr in early 2012 of an idea he had – to create bow ties using African print fabric.

“Whenever I would say I’m from Rwanda, people would give me a look of pity,” Rugamba told me in a previous interview. “I didn’t like that. So I wanted to tell the story of African dignity – that being Rwandan, and African, wasn’t a pitiful thing.” Bow ties were his way of making this point: “They exude elegance and dignity.”

At this point he had not a shred of experience in fashion or design; what he had was his Tumblr post on how he was going to use bow ties to tell the story of an Africa that is dignified and sophisticated.

By sheer coincidence, that was the very week when big high fashion designers Vivienne Westwood and Burberry were launching some “Africa-inspired” designs. Whenever people would google “African fashion” that week, they landed on his Tumblr post – and immediately, the buzz began growing, with orders and interview requests landing thick and fast.

Rugamba had to turn down many invitations to headline fashion events in the coming weeks, as he actually had no material to showcase yet. But that was the unlikely beginning of House of Tayo, and in the coming months, Rugamba spent many hours teaching himself everything he could about design and colour combinations, mostly from online tutorials and following fashion blogs.

***

Depending on the origin, fabric and production process, “African fabric” is not homogenous, but goes by many names and designs. Kitenge or chitenge is found in East and Central Africa, notably Zambia, Malawi, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ankara is West African, but not quite exactly – the fabric we now know as Ankara finds its origins not in Africa but in Indonesia, where locals there had long created prints on fabric by using wax-resistant dyeing (batik). It was brought to West Africa by Dutch traders. Shweshwe is a printed cotton fabric design found in southern Africa, and traditionally was only produced in three colours – brown, red and blue. Baoule is a heavy, thick cloth from Côte d’Ivoire made of five-inch-wide strips of cloth woven together. And kente is that distinctive Ghanaian pattern made of strips of orange, yellow and green.

The one thing that all these fabrics have in common is colour. African print is unapologetically colourful, and wearing it in public – depending on the intensity of coloniality in your society – is taken to be a very brave move, or a political statement. In Nairobi certainly, formal spaces are very monochrome, especially for men; blue, black and intervening shades (light blue, navy, grey, white) are taken to be the proper tones for what Kenyans call “official” clothes.

The taboo of colour in formal spaces in Kenya is a legacy of the colonial imagination, and its attendant Victorian ethic, which saw everything African as a problem to be corralled, controlled and disciplined. And for African men, especially, the pressure to aesthetically conform is even more acute, because as men within the structures of patriarchy (even under colonialism) there is at least the possibility of social climbing in a way that excludes women simply because they are not men. In that way, women tend(ed) to have more room to continue wearing their kitenges, khangas and lesos.

The one thing that all these fabrics have in common is colour. African print is unapologetically colourful, and wearing it in public – depending on the intensity of coloniality in your society – is taken to be a very brave move, or a political statement.

It seems that the more one is in contact with the logic of whiteness, the more disciplined one’s aesthetic will be. It is perhaps the reason why West Africans generally have a less complicated relationship with African prints – because they were colonised under indirect rule and did not have large numbers of white settlers to directly influence public life in that way. It is perhaps the reason why in a city like Nairobi, it was very difficult – until recently – to find anywhere to eat “African food” in public that was not a kibanda (roadside kiosk). Beyond the kibanda is white territory, and therefore African food could not find a place in a formal restaurant. Only in the past few decades has this been changing, with a growing acceptance of African fabric, music and food in public spaces. A restaurant chain like Nyama Mama, an upmarket, African-themed establishment offering local cuisine, could have never existed in the 1990s Nairobi of my childhood. Even so, the menu at Nyama Mama tends to offer “modern” fusions or reinterpretations of local dishes instead of serving them straight up, like serving ugali as baked fritters instead of the traditional stiff porridge.

***

Still, African designs are far from being unruly and chaotic. The repetitive motifs and designs of many fabrics are an example of fractals – geometric figures in which each part has the same character as the whole. Look closely at a piece of kitenge or Ankara fabric, and you are likely to see infinitely complex patterns that are repeated over and over again in an ongoing feedback loop.

Ron Eglash, professor at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor, in his book African Fractals: Modern Computing and Indigenous Design, explains how fractals permeate everything, from braided hairstyles and kente cloth to counting systems and the design of homes and settlements in many African communities. In his 2007 TED talk ‘The Fractals at the Heart of African Designs’, Eglash traces his journey into trying to understand African fractals, and the common pushback that he would get – that it was all “just intuition” and “Africans can’t possibly really be using fractal geometry…it wasn’t invented until the 1970s.”

Ron Eglash, professor at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor, in his book African Fractals: Modern Computing and Indigenous Design, explains how fractals permeate everything, from braided hairstyles and kente cloth to counting systems and the design of homes and settlements in many African communities.

“Well, it’s true that some African fractals are, as far as I’m concerned, just pure intuition,” he says in the talk. “So some of these things, I’d wander around the streets of Dakar asking people, ‘What’s the algorithm? What’s the rule for making this?’ and they’d say, ‘Well, we just make it that way because it looks pretty, stupid.’ [Laughter] But sometimes, that’s not the case. In some cases, there would actually be algorithms, and very sophisticated algorithms. So in Mangbetu sculpture [from DR Congo], you’d see this recursive geometry. In Ethiopian crosses, you see this wonderful unfolding of the shape.”

Eglash eventually traces these algorithms to sand divination that is common all over Africa, where priests divine your fortunes by making marks in the sand. These marks follow certain patterns that become diverse self-generating symbols that can be reduced to odd or even symbols, a kind of binary code.

Islamic mystics learned these divination patterns from African priests, and then took them to Spain in the 12th century. There they were kept alive among alchemy communities as the idea of geomancy, or divination through the earth.

German mathematician Gottfried Wilhehm Leibniz wrote about geomancy in his dissertation in the late 17th century, using a one and a zero instead of odd and even symbols. English mathematician George Boole took Leibniz’s binary code and refined it into Boolean algebra in 1847, and John von Neumann took Boolean algebra and created the digital computer in the mid 20th century.

So every digital circuit in the world, according to this research, has its unlikely origin very long ago in Africa, and the humble kitenge is just part of a much bigger legacy. How very apt that these same digital platforms – social media, television, music and the Internet – are fuelling the spread of a culture that they owe their very existence to.

Prof. Ron Eglash’s 2007 TED talk ‘The Fractals at the Heart of African Designs’.