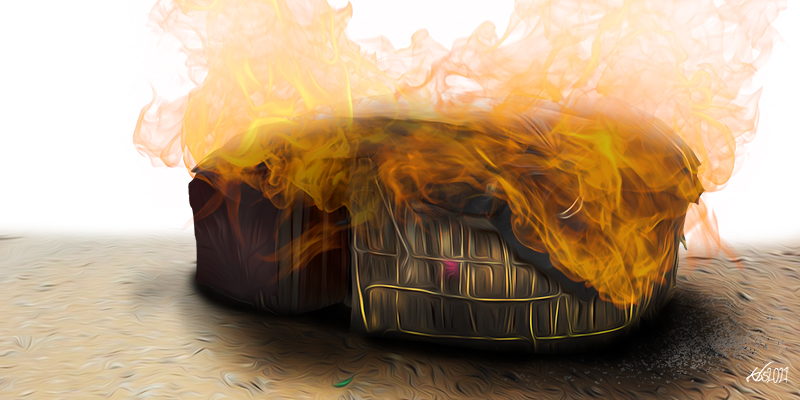

Just before Kenya’s 2007/2008 post-election crisis, a friend gave me an audio version of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. With my total visual disability, audiobooks and e-books are always a banquet. The novel features a group of middle-class British boys who find themselves on an island without adult supervision. At first they set up a liberal democratic type of government, with impressive standing orders for their deliberations. However, tensions build up after elections, leading to the formation of two mutually hostile tribes, and ultimately an orgy of violence that culminates in a fire that decimates the boys habitat. A British cruiser arrives just in time for a naval officer on board to call the boys to order and evacuate them from the now devastated island. It was not difficult to see an almost perfect correspondence between the characters in the novel and the ones who were splashed on the front pages of our newspapers during that dark chapter of our country’s history.

Around the world, politicians striving to get into power declare their unflinching commitment to peaceful demonstrations, but covertly, and sometimes even overtly, engage in violent activities. Similarly, although many regimes claim to be democratic, they ignore, muffle or suppress political dissent, often leading to political disobedience. In response, they often deploy security forces to crush such disobedience, resulting in a cycle of violence. Consequently, pertinent questions arise regarding the nature of truly non-violent political action, the moral justifications for it, and possible objections to it.

The nature of non-violent political action

There are authors that assume that “non-violent political action” is synonymous with “civil disobedience”. For example, in his seminal work, A Theory of Justice, the renowned American philosopher, John Rawls, defines civil disobedience as a public, non-violent, conscientious yet political act contrary to law, usually done with the aim of bringing about a change in the law or policies of the government. According to Rawls, by acting in this way one addresses the sense of justice of the majority of the community, and declares that in one’s considered opinion the principles of social cooperation among free and equal persons are not being respected. Nevertheless, in view of the fact that other writers consider the use of violence to be a type of civil disobedience, it is advisable to use the more specific term “non-violent civil disobedience” to eliminate the possibility of confusion.

One of the earliest articulations of non-violent civil disobedience is that by Plato in the Apology and the Crito. In the Apology, Plato presents Socrates as declaring that while he is committed to obeying the dictates of the state, he is obliged to disobey them whenever they conflict with the express will of the gods, even if the state threatens to put him to death for doing so. Socrates goes on to assert that if the Athenians were to sentence him to death, they would thereby injure themselves more than him. This position is pivotal to the doctrine of non-violent civil disobedience, which seeks to appeal to the conscience of the oppressor through the suffering he or she inflicts on the oppressed. In the Crito, Plato presents Socrates advancing three arguments in support of the view that it is virtuous to submit to the decision of the state to sentence him (Socrates) to death, and therefore that it is vicious for him to escape from prison: We ought not to harm anyone, yet escaping from prison would harm the state; we ought to keep our promises, yet escaping from prison would be tantamount to breaking the promise of loyalty to the state; we ought to obey and respect our parents and teachers, yet escaping from prison would be tantamount to disobedience and disrespect to the state, which enjoys the status of a parent or teacher.

As Roland Bleiker explains, Plato’s Socrates hence provided the precedent for a tradition of dissent that aims at resisting a specific authority, law, or policy considered unjust, while at the same time recognising the rulemaking prerogative of the existing political system as legitimate and generally binding. As indicated below, several other thinkers are associated with non-violent civil disobedience.

Étienne de La Boétie and David Hume

The basic assumption of non-violent civil disobedience is that governments are ultimately dependent on the fearful obedience and compliance of their subjects. This was succinctly stated by the sixteenth century French jurist and political philosopher, Étienne de La Boétie (1530–1563), who wrote his seminal essay, Discours de la Servitude Volontaire (The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude) in 1552–1553. For La Boétie, all that the oppressed masses need to do in order to overthrow the tyrant is to withdraw their cooperation from him:

He who … domineers over you has only two eyes, only two hands, only one body, no more than is possessed by the least man among the infinite numbers dwelling in your cities; he has indeed nothing more than the power that you confer upon him to destroy you. Where has he acquired enough eyes to spy upon you, if you do not provide them yourselves? How can he have so many arms to beat you with, if he does not borrow them from you? The feet that trample down your cities, where does he get them if they are not your own? How does he have any power over you except through you? How would he dare assail you if he had no cooperation from you? What could he do to you if you yourselves did not connive with the thief who plunders you, if you were not accomplices of the murderer who kills you, if you were not traitors to yourselves? …. Resolve to serve no more, and you are at once freed. I do not ask that you place hands upon the tyrant to topple him over, but simply that you support him no longer; then you will behold him, like a great colossus whose pedestal has been pulled away, fall of his own weight and break into pieces.

The Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711–1776) independently discovered the principle of the goodwill of the populace as the ground of government two centuries after La Boétie, and stated it as follows:

Nothing is more surprising to those who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye than to see the easiness with which the many are governed by the few; and the implicit submission, with which men resign their own sentiments and passions to those of their rulers. When we enquire by what means this wonder is effected, we shall find that, as Force is always on the side of the governed, the governors have nothing to support them but opinion. It is, therefore, on opinion only that government is founded; and this maxim extends to the most despotic and most military governments, as well as to the most free and most popular.

Henry David Thoreau

While the thoughts of La Boétie and Hume on non-violence were purely theoretical, the 19th-century American thinker, Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), engaged in a non-violent action in an attempt to challenge a specific public policy. He refused to pay the state poll tax imposed by the US government to prosecute a war in Mexico and to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law. Consequently, in July 1846, he was arrested and jailed. He was supposed to remain in jail until a fine was paid, which he also declined to pay. However, without his knowledge or consent, relatives settled the “debt”, and a disgruntled Thoreau was released after only one night. The incarceration was brief, but it has had enduring effects, as it prompted Thoreau to write his seminal 1848 essay, On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. Thoreau shared with La Boétie and Hume the view that states continue to exist because of the acquiescence of the citizenry.

Nothing is more surprising to those who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye, than to see the easiness with which the many are governed by the few.

Nevertheless, as Lawrence Rosenwald correctly observes, although proponents of non-violent action often cite Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience” in support of their strategy, he did not rule out the use of violence in politics. Indeed, after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, and still more after John Brown’s raid, Thoreau defended violent action on the same grounds as those on which he had defended non-violent action in On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. This is evident in Thoreau’s 1859 work, A Plea for Captain John Brown.

Mohandas Karmachand Gandhi

One of the best known organisers of non-violent civil disobedience is the Indian nationalist, Mohandas Karmachand Gandhi, commonly referred to as “Mahatma (“Great Soul”) Gandhi” (1869–1948). As a young lawyer in South Africa protesting the government’s treatment of immigrant Indian workers, Gandhi was deeply impressed by Thoreau’s essay on civil disobedience. What is less known is that Gandhi believed that the Indians in South Africa deserved equal treatment with the Europeans in the country, and was in fact incensed that they were being treated like the majority indigenous peoples there. Thus in 2018, the University of Ghana removed Gandhi’s statue from its exalted place following protests from the university’s lecturers. For now, however, let us focus on Gandhi’s policy of non-violence.

Gandhi called his overall method of non-violent action Satyagraha. In his 1961 book, Non-Violent Resistance (Satyagraha), he wrote:

Satyagraha is literally holding on to Truth and it means, therefore, Truth-force. Truth is soul or spirit. It is, therefore, known as soul-force. …. The word was coined in South Africa to distinguish the non-violent resistance of the Indians of South Africa from the contemporary ‘passive resistance’ of the suffragettes and others.

Gandhi was at pains to make a sharp distinction between “passive resistance” and Satyagraha. The main difference, according to him, is that passive resistance is not committed to love, but is rather an expedient strategy that can be easily abandoned whenever it was convenient to use violence. On the other hand, Satyagraha is committed to non-violence, considering itself to be the very opposite of violent resistance. He believed in confronting his opponents aggressively, in such a way that they could not avoid dealing with him. The difference, as Mark Shepard points out, was that the non-violent activist, while willing to die, was never willing to kill. In support of non-violent action, Gandhi argued that if the world were to pursue violence to its ultimate conclusion, the human race would have become extinct long ago. He is often quoted as having said that “an eye for an eye would make the world blind”.

Mark Shepard notes that Gandhi practised two types of Satyagraha in his mass campaigns. The first was civil disobedience, which entailed breaking a law and courting arrest. The second was non-cooperation, that is, refusing to submit to the injustice being fought. It took such forms as strikes, economic boycotts and tax refusals.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Gandhi’s thought and practice greatly influenced the thinking of the African-American Civil Rights Movement leader, Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929–1968). According to Andrew Altman, in contemporary political thought, the term “civil rights” is indissolubly linked to the struggle for equality of African Americans during the 1950s and 1960s, whose aim was to secure the status of equal citizenship between African and European Americans. After slavery was abolished, the US federal Constitution was amended to secure basic rights for African Americans. In 1877, however, the federal government moved to frustrate efforts to enforce those rights. As a result, state constitutions and laws were modified to exclude African Americans from the political process.

Martin Luther King, Jr. catapulted to fame when he came to the assistance of Rosa Parks, the Montgomery, Alabama African American seamstress who, on the 1st of December, 1955, was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated Montgomery bus to a European American passenger. In Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story, King Jr. was emphatic that he was not the founder of non-violent civil disobedience among African Americans; rather, he merely served as their spokesman. Like Gandhi, King, Jr. states that his adoption of non-violent civil disobedience was inspired by Thoreau’s On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. Nevertheless, he attributes the details of his strategy to the work of Mohandas K. Gandhi.

Thoreau shared with La Boétie and Hume the view that states continue to exist because of the acquiescence of the citizenry.

In Letter from a Birmingham Jail, King, Jr., like Gandhi before him, advanced the view that the purpose of direct mass action is to attain a situation in which the opponent is willing to negotiate. In Stride Toward Freedom, he outlines several basic aspects of the doctrine of non-violence as follows: It is not for cowards, but is actually a method of resistance; it seeks to win the friendship and understanding of the opponent; it attacks forces of evil rather than persons who happen to be doing the evil; it is willing to accept suffering without retaliation; it avoids not only external physical violence, but also internal violence of spirit; it is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice.

Moral justifications for non-violent political action

As Bernard Gert explains, to justify an action is to show that it is rational. Besides, George Fletcher points out that a justification speaks to the rightness of the act, while an excuse focuses on whether or not the actor is accountable for a concededly wrongful act. An unflinching commitment to non-violent political action can be morally justified on at least nine counts.

Violence breeds violence by stimulating the desire for revenge, with the grim possibility of an endless cycle of violence. Because of the physical and psychological harm caused by violence, it often leaves the two sides as longstanding enemies. Even when an armed insurgency is victorious, the final outcome is often disastrous, yet no such losses are associated with non-violent political action.

Armed resistance tends to push undecided elements of the population towards the government, as any effects of the violence they suffer serves to convince them that the purported “liberators” are actually “terrorists”. In sharp contrast to this, government repression against unarmed resistance movements usually creates greater popular sympathy for the regime’s opponents. According to Jerry Tinker, this explains the tendency of many governments, when faced with non-violent resistance, to emphasise any violent fringes that may emerge.

As Stephen Zunes cautions, quite frequently, regimes which come to power through violent means soon forget their pledges to uphold personal liberties. According to Kimberley Brownlee, throughout history, acts of non-violent political action have helped to force a reassessment of society’s moral parameters. Indeed, it is partly for this reason that today’s dissidents are often tomorrow’s heroes.

Like Gandhi before him, advanced the view that the purpose of direct mass action is to attain a situation in which the opponent is willing to negotiate.

In his autobiography, the British philosopher, Bertrand Russell, observes that engaging in civil disobedience often leads to wide dissemination of a position which would have otherwise received inadequate coverage in mass media. Mark Shepard notes that even in revolutions that are primarily violent, the successful ones usually include non-violent civilian actions. Shepard further observes that there are other cases in which violence would work, but so would non-violent action with much less harm. Kelley Ross observes that by refraining from causing physical damage which is, by its very nature irreversible, non-violent political action caters for the fact that we may very well be wrong in holding a particular political position.

Answering objections to non-violent political action

At least six objections have been levelled against non-violent political action, but answers to them are readily available.

First, objectors point out that non-violent political action results in harm, and any harm is undesirable. However, proponents of non-violent political action reply that the kind of harm it causes is much less grievous than that from violent political action. Nevertheless, some critics have questioned this assertion. Yet, while the issue may not be conclusive, our intuitions suggest that this is the case: a stone hurled at the police or a tear gas canister hurled at a crowd are much more harmful than a peaceful sit-in.

Second, some critics claim that non-violent political action is unbearably slow in achieving the desired results. Yet, as Mark Shepard observes, even violent actions take long to produce the desired results. Shepard quotes Theodore Roszak as having once commented: “People try non-violence for a week, and when it ‘doesn’t work’, they go back to violence, which hasn’t worked for centuries.”

Engaging in civil disobedience often leads to wide dissemination of a position which would have otherwise received inadequate coverage in mass media.

Third, some thinkers have charged that there are cases in which non-violence cannot produce the desired results, as has been experienced in highly repressive regimes. Nevertheless, the cases in which non-violent action would not work are also often cases in which violence would prove pointless or worse. Indeed, Mark Shepard points out that where violent efforts would be easily contained or instantly crushed, non-violent action may be the only realistic choice.

Fourth, according to David Lyons, some objectors contend that even those who are treated unjustly can have moral reason to comply with unjust laws – as when non-violent political action would expose some persons such as children and the very old to risks they have not agreed to assume. However, such casualties are to be found both in instances of violent and non-violent political action, as long as at least one side in a political contest shows no commitment to non-violence.

Fifth, according to Roland Bleiker, some critics charge that non-violent political action is merely a manipulative strategy by the Western liberal democratic establishment to maintain the status quo. However, there is evidence that it has the potential to effect radical change in any society, as was the case with Gandhi in India, and, to an extent, with Martin Luther King Jr. in the US.

The culture of violent political action by those who aspire to power, as well as by those who have power and wish to retain and enhance it, risks plunging society into a swamp of self-destruction; and unlike the case of the boys in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, there is no assurance that the cruiser will arrive just in time. In fact, in several cases on our continent, it did not arrive at all.