In 2014, Belgian documentary artist Max Pinckers was invited to the Archive of Modern Conflict in London, where he came across a collection of British propaganda material relating to the 1950s “Mau Mau Emergency Crisis” in Kenya. Since then he has been working with various Mau Mau War Veterans Associations in Kenya, with a particular focus on using photography to (re-)visualize the fight for independence from their personal perspectives. This includes mass graves, former detention camp buildings, locations of former mobile gallows, cave hideouts, oral witness testimonies, portraits and demonstrations of personal experiences.

This ongoing documentary project titled Unhistories departs from the Hanslope Disclosure in which British colonial archives were destroyed, hidden and manipulated. Known as Operation Legacy in the 1950s, the British colonial administration in Kenya destroyed much of the documentation relating to the Emergency prior to their departure in 1963. Unhistories is a collaboration with Mau Mau veterans, Kenyans who survived the colonial violence, historians, artists, activists, writers, archives, universities and museumsto fill in the missing gaps of the archives.

This second part of the Unhistories series covers the ‘prohibited areas’ where the fighting took place, the mobile gallows, the trials, torture, and prisons.

A mass holding cell at former Mweru Works Camp that today functions as a classroom. The original cell buildings did not have windows. The barbed wire can still be seen between the walls and the roofing. Mweru High School, Mukurwe-ini, Nyeri County, 2015.

The Colonial Executioner’s residence at former Mweru Works Camp. Mweru High School, Mukurwe-ini, Nyeri County, 2015.

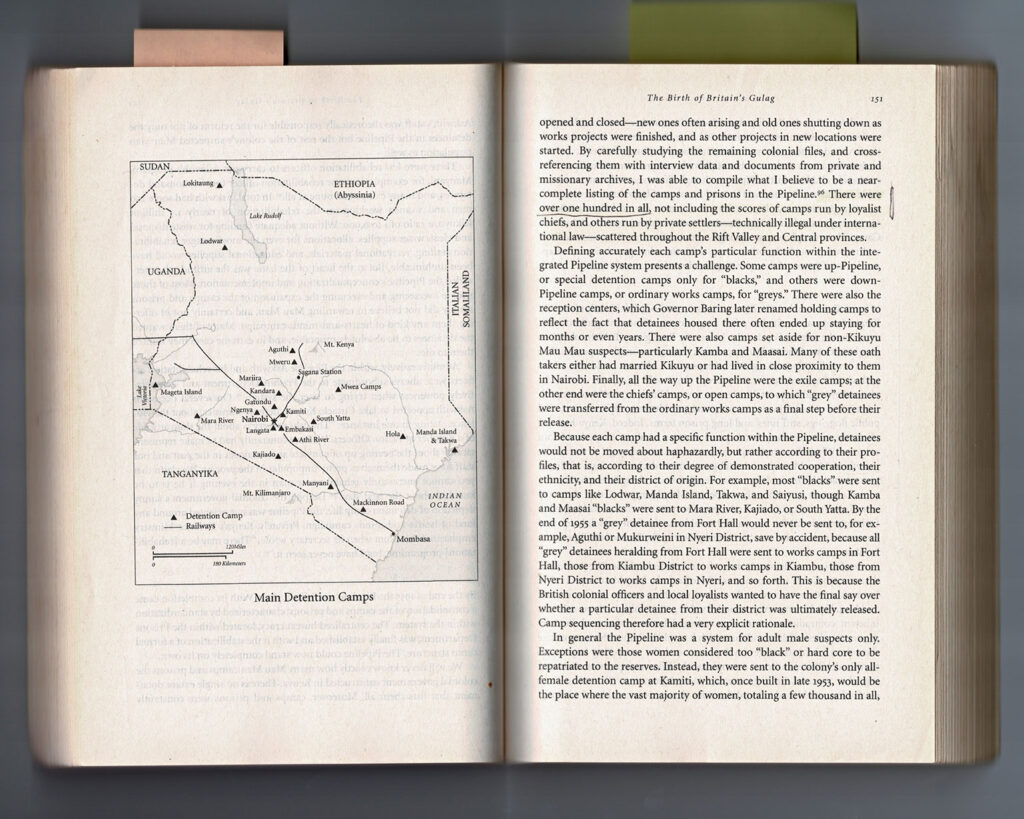

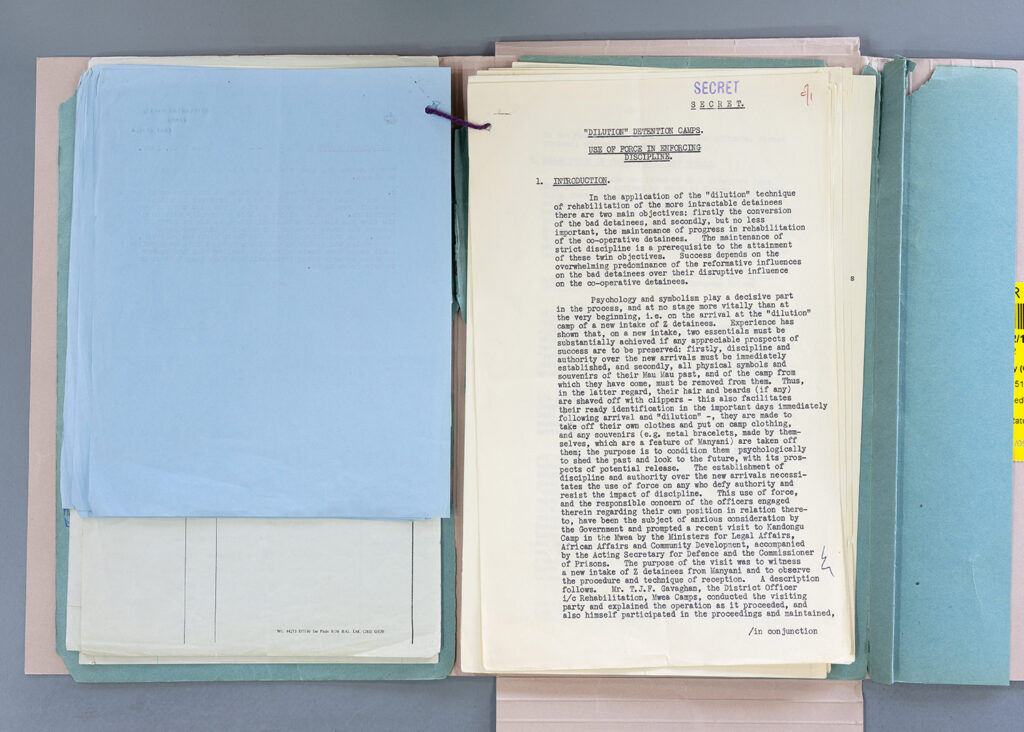

Thomas Askwith, Commissioner for Community Development in Kenya (1911-2001), developed the “pipeline” in 1953. A large-scale system to “rehabilitate” suspected supporters and fighters of the Mau Mau movement. As military operations ramped up in 1954, it was converted into a system of punitive detention, torture and collective punishment. Concerned by the lack of standardized procedures and heightened use of violence, he was a spirited advocate for the humane treatment of prisoners in detention camps. For his efforts, he was quietly marginalized by the colonial administration.

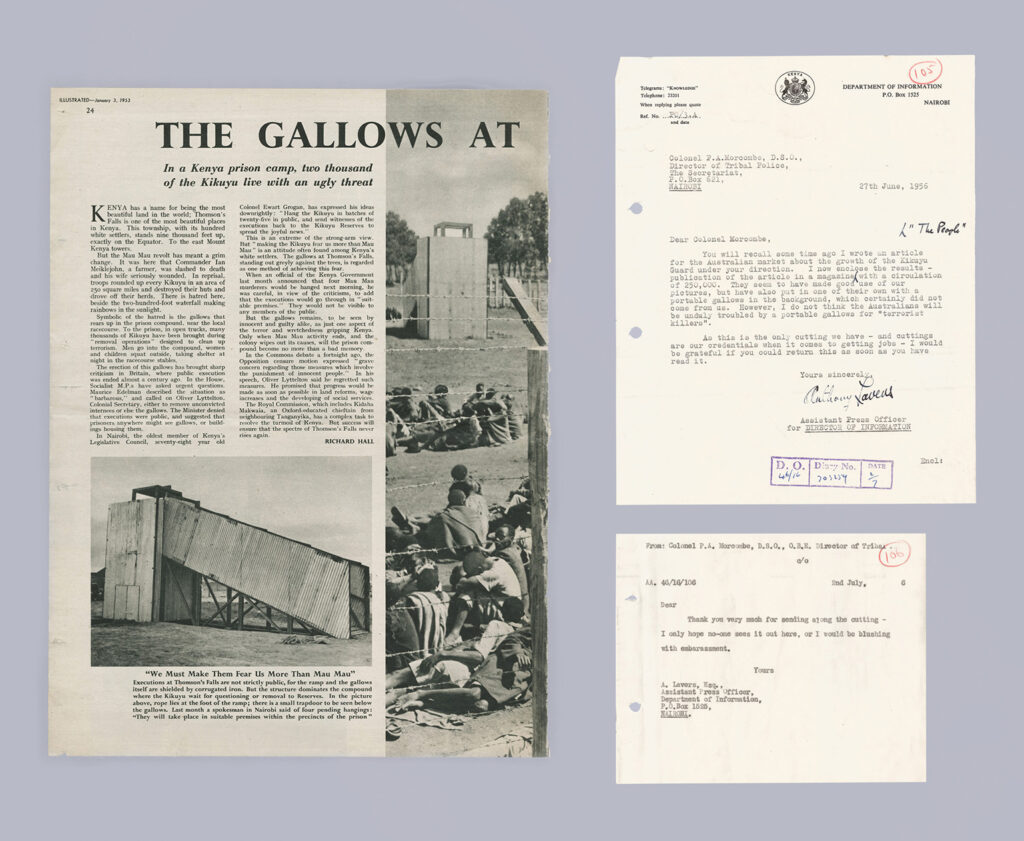

“The Gallows at Thomson’s Falls” by Richard Hall, Picture Post, Illustrated, p. 24, January 3, 1953. AMC, A 5072. The Archive of Modern Conflict, London, UK. Correspondence between Colonel Morcombe and Assistant Press Officer Lavers on behalf of the Director of Information, 1956 KNA, OP/1/998/105 and KNA, OP/1/998/106. Kenya National Archives, Nairobi, Kenya.

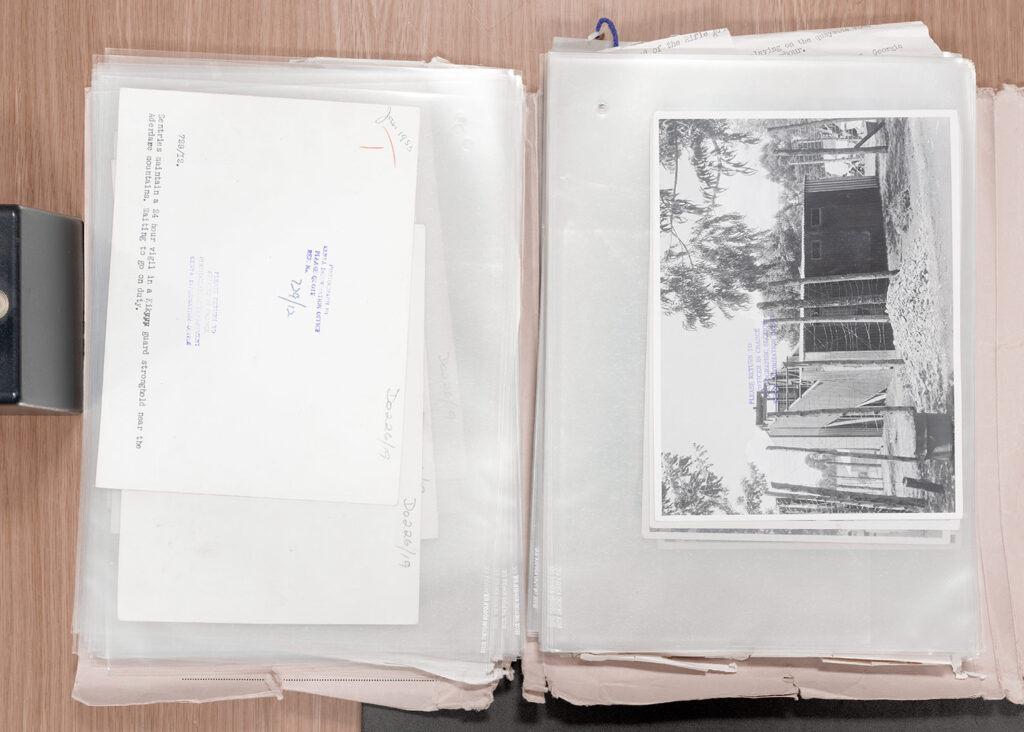

TNA, CO 1066/9. The National Archives, Kew, UK.

Mobile Gallows

Public hangings were outlawed in Britain for over a century but took place in Kenya during the emergency. A mobile gallows was transported by the British around the country to carry out the execution of Mau Mau suspects. Between 1952 and 1958, 1,090 Kikuyu were hanged. In no other place, and at no other time in the history of British imperialism, was state execution used on such a scale.

Mburu wa Gitou

The gallows stood here and this cemented block is where the bodies would drop dead before they were wrapped up and hauled out. During the hangings there was a Catholic Father at the door. He prayed and after the conviction, he would sign, break the pen and wash his hands. 57 people were hanged here.

The hanging begun at 11 at night and we could hear them saying: “We have gone, we have died and you have been left. Never let go of this land, for it is what we die for.” They all died with a fistful of soil in their hand.

Once hanged, the bodies were not disposed of immediately, they were seen by everybody so that people would be afraid. So that they would stop the war. But they would dare not surrender. The bodies were hauled into a truck in the morning. The army trucks rode away with legs dangling from the back.

The monument serves as a reminder of those who were hanged in this nation, who died for independence. We can come for prayers here. The design of the monument is made in collaboration with the National Museums of Kenya, and we will engrave their names on the wall.

— Mburu wa Gitou (Chairman of the Kenya Unity for Memorial, Peace, Heritage and Culture Organization), Githunguri, Kiambu County, 2019

Elkins, Caroline. Imperial Reckoning: the Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2006.

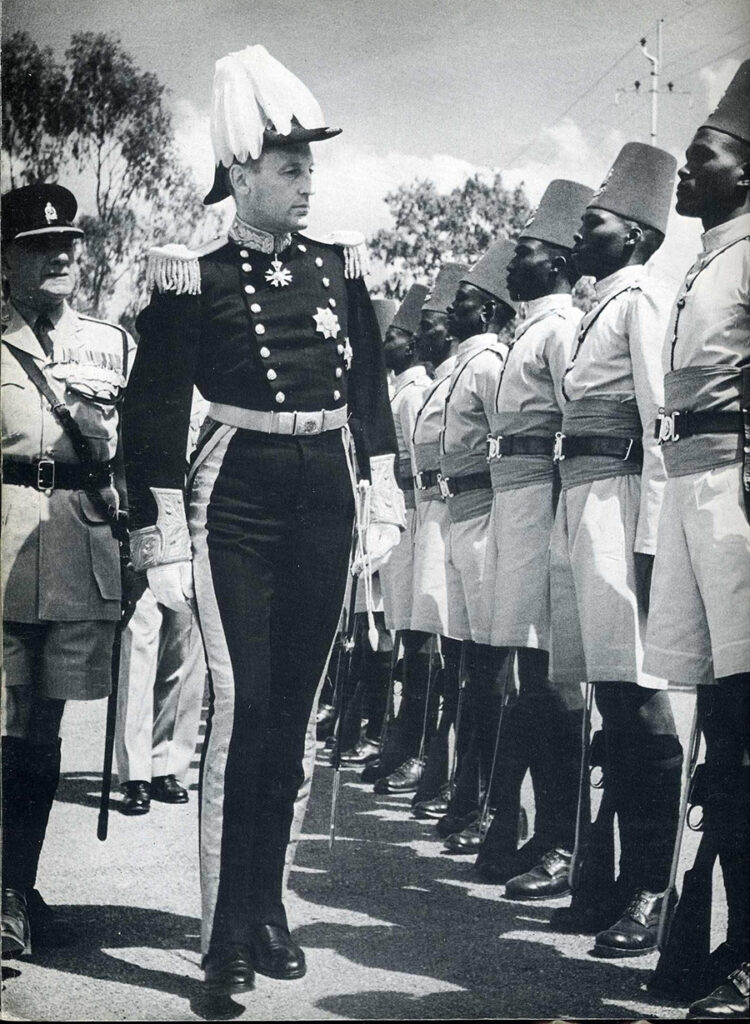

Sir Evelyn Baring, KG, GCMG, KCVO (1903-1973) was the Governor of Kenya from 1952 to 1959. Together with Colonial Secretary Alan Lennox-Boyd, he played a significant role in the government’s efforts to cover up the abuses carried out during the suppression of the Mau Mau and keep them secret from the British public.

Paul Mwangi Mwenja

During the struggle for independence I was a student at a school where the King’s African Rifles were staying. They were fighting for the British, but the soldiers became our friends. They showed us everything, and that’s when I learned how the gun works.

I began making homemade guns. You could only use one bullet at a time. You’d take out the cartridge and put in another. We used these guns to hunt European soldiers. When we’d get one—we would ambush or hide beside him in the bush and shoot him—we’d take his gun. That way we’d gain a gun. A new gun.

We used water pipes to make these guns. And then we were using door locks. We would sharpen the tip of the door lock and use a spring or elastic rubber to hit the bullet, so that oxygen would get in and the bullet fires. The guns we were making could be taken apart while traveling. In order to hide it in the kabuthi, the jacket, you could break it up into two pieces, and when you wanted to be in action you could put it together again. It was easy to travel with.

— Paul Mwangi Mwenja (MMWVA Murang’a Branch Secretary), Murang’a, 2019

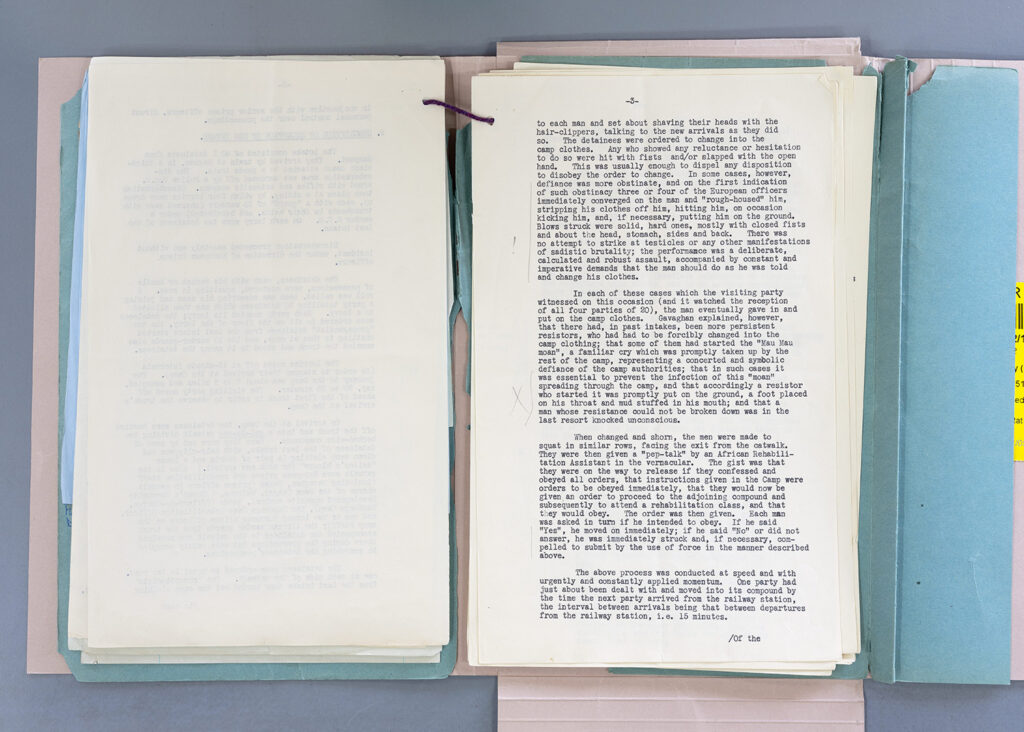

Terence Gavaghan, MBE (1922-2011) was a British colonial district officer in Kenya responsible for six detention centers in Mwea during the emergency. He was the chief architect of the “dilution technique” and was known for implementing the systematic destruction of bodies and minds in Kenya’s detention camps. During Operation Legacy, Gavaghan also participated in the burning of documents in incinerators and ensured that others would be permanently held under lock and key. The colonial government’s chief torturer in Kenya was also one of its chief archivists in the final days of rule.

Inscription on back of print: “Near the burning swamp, Terry Gavaghan points out to his Officers and the Samburu tribesmen, their routes in search of the Kikuyu gangsters.” TNA, 1066/6/845/6. The National Archives, Kew, UK.

Inscription on back of print: “Terry Gavaghan talking to his Samburu tribesmen prior to searching the papyrus swamp.” TNA, 1066/6/845/2. The National Archives, Kew, UK.

TNA, CO 822/1251. The National Archives, Kew, UK.

Terence Gavaghan interviewed in BBC Correspondent documentary Kenya: White Terror, aired on November 17, 2002.

Members of the Mukurwe-ini Mau Mau War Veterans Association demonstrate how people were rounded up and sent to detention camps, Mukurwe-ini, Nyeri County, 2015.

Beninah Wanjugu Kamujeru demonstrates how she was interrogated, Murang’a, 2019.

Extra’s on Death Row

Simba (1955), directed by Brian Desmond Hurst, starring Dirk Bogarde and Virginia McKenna, was filmed in Kenya at the height of the emergency. The film tells the story of a White settler family who find themselves involved in the Mau Mau uprising. The characterization of the Mau Mau movement is conformed to what was by then a well-established British stereotype, using all of the conventional colonial imagery. South African producer Peter de Saringy, who was responsible for most of the location filming in Kenya, explained that they used Mau Mau prisoners in some of the scenes as extra’s. They had obtained the prisoners from a jail on the outskirts of Nairobi, with the full co-operation of the prison authorities, who “brought them from their cages” to be filmed at the perimeter of the gaol. Several of the prisoners were reported as being handcuffed to prevent their escape while the filming took place. Three of the eleven men filmed were taken to the gallows only three days later.

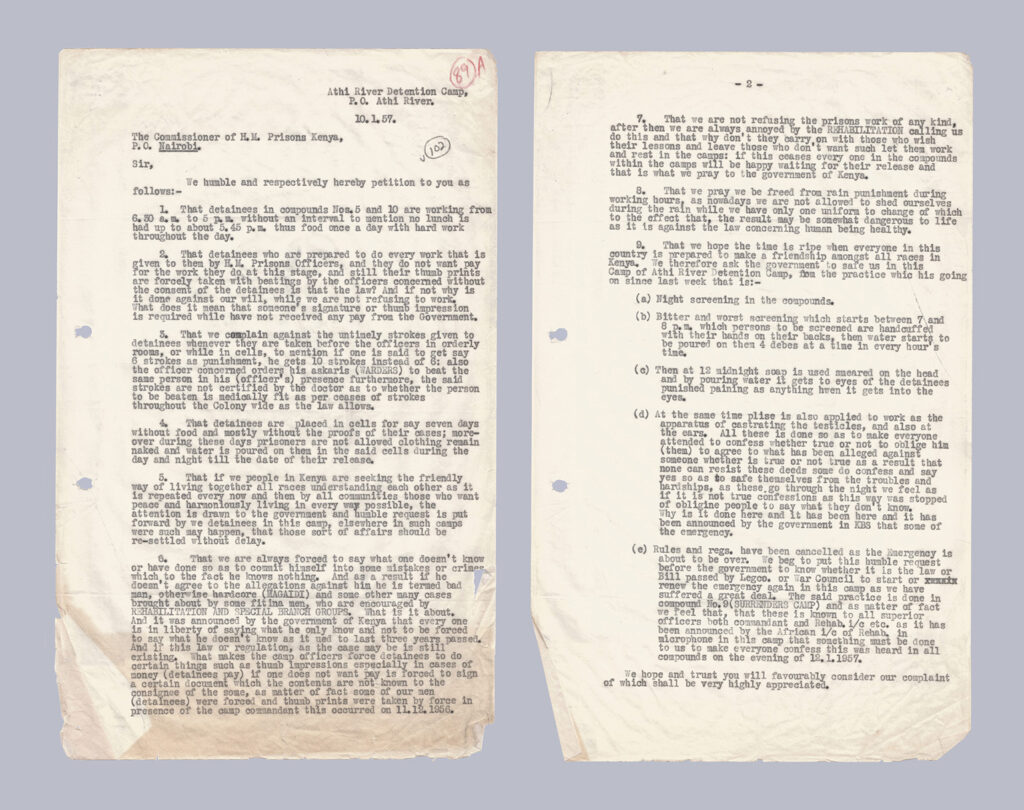

Complaints by detainees, Athi River Detention Camp, January 10, 1957 KNA, JZ/7/4/89A. Kenya National Archives, Nairobi, Kenya.