The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated global economies, healthcare systems, and institutions including universities. It has accelerated trends towards the digitalisation of economic and social life and the need for digital skills. Here we focus on how African higher education institutions can embrace these changes in order to survive and succeed in the emerging “new normal”. The pandemic has exposed the huge developmental challenges that African universities face, while at the same time it has opened immense new opportunities for transformation. The continent is indeed at the proverbial crossroads in which the multiple demographic, economic, ecological, political and social problems confronting it can be turned into possibilities if managed with strategic, systemic and smart interventions, and the seriousness they deserve.

One of the continent’s biggest assets is its rapid population growth. If properly harnessed, the youth bulge not only promises to become the continent’s largest population ever, but also potentially its most educated and skilled. It is this population upon whose weighty shoulders the continent has placed a historic opportunity to overcome its half millennia of global marginality, underdevelopment and dependency, and begin realising the long-deferred dreams of constructing integrated, inclusive, innovative democratic developmental states and societies. The ghastly alternative is a Malthusian nightmare of hundreds of millions of uneducated, unemployable, and ungovernable marauding masses of young people, a future of unimaginable dystopia.

Educational institutions including universities have a monumental responsibility to turn the youth explosion into a dividend rather than a disaster. This entails removing prevailing skills and jobs mismatches, upgrading the employability skills of the youth, and strengthening and reforming educational institutions to prepare them for the jobs of the 21st century, which increasingly require digitalised competencies. For this to happen, higher education institutions themselves must undergo and embrace digital transformation. COVID-19 suddenly shoved universities—which are renowned for their aversion to change and notoriously move at a snail’s pace—into the future as they moved teaching and learning, administrative and support services, research activities, and even their beloved seminars, symposia, and conferences online.

The ghastly alternative is a Malthusian nightmare of hundreds of millions of uneducated, unemployable, and ungovernable marauding masses of young people, a future of unimaginable dystopia.

Here we examine the digital transformation of higher education. First, we begin by placing the changes, challenges, and opportunities facing contemporary Africa in the context of the mega trends of the 21st century in which the digitalisation of the economy, society, politics, work, education, and even leisure and interpersonal relations increasingly loom large. Second, we examine global developments in the digitalisation of higher education. Third, we present a twelve-point digital transformation agenda for African universities. Finally, the question of building Africa’s technological capacities to ensure that the continent is a major technological player and not pawn, dynamic creator not just passive consumer of technology, is broached and analysed. We believe without it, the digital transformation of not only African universities, but the continent’s economies and societies will remain incomplete and keep them in perpetual underdevelopment.

The mega trends of the 21st century

There is no shortage of diagnoses and prognoses of the trends and trajectories of the 21st century by international agencies, consultancy firms, governments, academics and pundits. The projections and predictions of the future are as varied as their progenitors and prognosticators, reflecting their divergent institutional, ideological, intellectual, and even individual investments and proclivities. At a more collective and policy level, they find articulation in national, regional, and global visions. Examples include Kenya’s Vision 2030, East Africa’s Vision 2050, the African Union’s Agenda 2063, and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals.

The futuristic soothsayers were particularly busy at the turn of the new century and millennium but they are by no means gone. A recent compelling and controversial forecast of the unfolding century can be seen in Yuval Noah Harari’s book, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. He identifies five developments under which he outlines specific challenges. The first is what he calls “The Technological Challenge” (under which he discusses disillusionment, work, liberty, and equality); second, “The Political Challenge” (community, civilisation, nationalism, religion, and immigration); third, “Despair and Hope” (terrorism, war, humility, God, secularism); fourth, “Truth” (ignorance, justice, post-truth, science fiction); and fifth “Resilience” (education, meaning, meditation).

One of us (Zeleza) is writing a book, The Long Transition to the 21st Century: A Global History of the Present, which seeks to examine the major features of the contemporary world, how they came about, and their differentiated manifestations in different world regions. It is divided into five chapters. The first is entitled, “The Rise of the People” (on social movements and struggles for emancipation and empowerment); the second, “The Emergence of Planetary Consciousness” (on the development of global consciousness fostered by the processes of globalisation and growth of environmental awareness); the third, “The Digitalisation of Everything” (on transformations brought about by digital information and communications technologies on every aspect of social life); the fourth, “The Restructuring of the Geopolitical Order” (on shifting global hegemonies, hierarchies and struggles); and the fifth, “The Great Demographic Reshuffle” (on changing demographic regimes and migration processes and patterns).

Three of these phenomena are particularly pertinent here. The first centers around the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The term often refers to the emergence of quantum computing, artificial intelligence, the internet of things, machine learning, data analytics, big data, robotics, biotechnology, nanotechnology, and the convergence of the digital, biological, and physical domains of life, and the digitalisation of communication, connectivity, and surveillance. Africa has participated in the three revolutions lately as a pawn rather than a player.

During the First Industrial Revolution of the mid-18th century the continent paid a huge price through the Atlantic slave trade that laid the foundations of the industrial economies of EuroAmerica. Under the Second Industrial Revolution of the late 19th century Africa was colonised. The Third Industrial Revolution that emerged in the second half of the 20th century coincided with the tightening clutches of neo-colonialism for Africa. If the continent continues to be a minor player, content to import technologies invented and controlled elsewhere, its long-term fate might not be confined to marginalisation and exploitation as with the other three revolutions, but descent into irreversible global irrelevance.

The second major trend centers on hegemonic shifts in the world system. The global hegemony of the West that has survived over the last half millennium appears to be drawing to a close with the rise of Asia and other emerging economies of the global South. A harbinger of the hegemonic rivalries that are likely to dominate much of the 21st century is the trade war between a declining United States and a rising China. The consequences of previous hegemonic struggles for global power for Africa varied.

The imperial rivalries between Britain, the world’s first industrial power, and industrialising Germany, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries culminated in the “New Imperialism” that engendered both the colonisation of Asia and Africa and World War I. In contrast, the superpower rivalry between the former Soviet Union and the United States spawned the geopolitical spaces for Asian and African decolonisation. What will the current reconfiguration of global power bring for Africa? How can Africans ensure it creates opportunities for development?

If the continent continues to be a minor player, content to import technologies invented and controlled elsewhere, its long-term fate might be descent into irreversible global irrelevance.

Africa’s prospects in the 21st century will be inextricably linked to the third major transformation, namely, the profound changes in world demography. This is characterised by, on the one hand, an aging population in the global North and in China thanks to its one-child policy imposed from 1979 to 2015, and on the other, population explosion in some regions of the global South, principally Africa. Currently, 60 per cent of the African population is below the age of 25.

The continent is expected to have, on current trends, 1.7 billion people in 2030 (20 per cent of the world’s population), rising to 2.53 billion (26 per cent) in 2050, and 4.5 billion (40 per cent) in 2100. It is estimated that in 2100 Africa will have a large proportion of the world’s labour force. Thus, educating and skilling Africa’s youths is critical to the future of Africa itself and the rest of the world. Doing so will yield a historic demographic dividend, whereas failure will doom Africa’s prospects for centuries to come.

The digitalisation of higher education

Higher education institutions have a fundamental role to play in enhancing the development and nurturing of demand-driven digital and technical skills because of their quadruple mission, namely, teaching and learning, research and scholarship, public service and engagement, and innovation and entrepreneurship. This mission is particularly pressing for African universities, the bulk of which were established after independence by the developmentalist state as locomotives to catapult the continent from the perils of colonial dependency and underdevelopment to the possibilities of sustainable development.

As with every other sector, higher education institutions are facing massive transformations that require continuous reform to make them better responsive to the unyielding and unpredictable demands of 21st century economies, societies, polities, and ecologies. The restructuring of universities is necessitated by pervasive and escalating digital disruptions, rising demands for public service and engagement, changes in the credentialing economy, and escalating imperatives for lifelong and lifewide learning. Given the changing nature and future of jobs, today’s youth will not only have multiple jobs but several careers, some of which have not even been invented.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic exposed widespread differences and inequalities in terms of national capacities to manage the crisis and its costs. It forced higher education institutions around the world to embrace distance teaching and learning using online platforms as never before. They had to learn to do more with less as their financial resources became strained as never before and their faculty and students faced the stresses of massive readjustment. Many institutions rose to the occasion as they leveraged existing and acquired new digital technologies, while faculty and students adapted to the new normal.

The unprecedented crisis revealed differentiated institutional resources, access to information technology, and capabilities to transition to online teaching and learning. The pandemic also underscored challenges of access by faculty and students to digital technologies and broadband based on the social dynamics of class, location, gender, and age. It simultaneously exposed and eroded prevalent distrust and discomfort with online compared to face-to-face teaching and learning, and widespread concerns about the quality of online instruction by students, parents and employers.

A few months before the world was engulfed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the International Association of Universities published an important report on Higher Education in the Digital Era. The report contained results of a global consultation encompassing 1,039 public and private higher education institutions in 127 countries (29 per cent from Europe, 27 per cent Asia and the Pacific, 21 per cent Africa, 17 per cent Middle East, 5 per cent Latin America and Caribbean). Globally, only 16 per cent of respondents found national regulatory policies supportive for higher education transformation in the digital era; 32 per cent mostly supportive with some exceptions; 36 per cent variably supportive and constraining; and 17 per cent mostly unsupportive. The responses from African institutions were 19 per cent, 26 per cent, 37 per cent, and 19 per cent, respectively. Overall, Asia had the most positive assessment, and Europe the most negative.

Today’s youth will not only have multiple jobs but several careers, some of which have not even been invented.

The report also investigated the national financial framework for higher education. Only 7 per cent globally deemed the frameworks highly supportive; 26 per cent mostly supportive with some exceptions; 43 per cent variably supportive and constraining; and 24 per cent mostly unsupportive. Overall, Asia led with 43 per cent, reporting highly and mostly supportive, followed by the Middle East at 40 per cent, Latin America and the Caribbean at 36 per cent, Africa at 30 per cent, and Europe at 27 per cent.

As for Internet infrastructure, the variations favoured the more developed regions. The proportion of individuals out of 100 using the Internet stood at 80.9 in the developed countries, 45.3 in developing countries, 19.5 less developed countries, and a world average of 51.2. Europe led with 79.6, followed by the Commonwealth of Independent States 71.3, Americas 69.6, Arab States 54.7, and Africa was at the bottom with 24.4. The quality of the Internet infrastructure in Africa is exceptionally poor: only 7 per cent find it satisfactory, compared to 39 per cent in Europe, and 21 per cent in Africa find it not good, compared to 2per cent in Europe.

There are also glaring inequalities in the spatial distribution of Internet facilities. At a global level, 34 per cent reported that Internet infrastructure was good in big cities, but poor in rural areas. The equivalent figures were 58 per cent for Latin America and the Caribbean, 47 per cent for Asia and the Pacific, 39 per cent for Africa, 26 per cent for Middle East, and 17 per cent for Europe.

Clearly, enhancing the technological transformation of higher education depends on the levels of national investments in IT infrastructure. The global digital divide remains real and daunting. High inequalities in the spatial distribution of Internet facilities deprives tens of millions of people around the world, especially Africa, access to information, knowledge and networks. Equally critical are institutional investments in IT and here too, Africa lags awfully behind. According to the IAU report, 39 per cent noted digital infrastructure was a significant obstacle at the institutional level compared to 7 per cent in Europe, representing the highest and lowest global levels, respectively.

Higher education and research institutions tend to use national research education networks (NRENs) as an alternative to the commercial Internet Service Providers. On the issue of national support for NRENs, Africa is also at the bottom with 67 per cent of respondents noting the level of support was very or somewhat high compared to the world average of 71 per cent, and 74 per cent for Asia and Pacific, 73 per cent for Middle East, 72 per cent for Europe, and 50 per cent for Latin America and Caribbean. Africa led in the use of NRENs by higher education institutions at 70 per cent compared to a world average at 62 per cent, the same as Asia and Pacific, and 68 per cent for Latin America and the Caribbean, 64 per cent for Middle East, and 56 per cent for Europe.

Institutional commitment to digital transformation is obviously critical to making the necessary investments in IT infrastructures. The IAU’s report shows generally high levels of commitment from institutional leaders. Africa led with 77 per cent claiming strong leadership support, compared to 74 per cent for Middle East, 73 per cent for Asia and Pacific, 70 per cent for Europe and 61 per cent for Latin America and Caribbean. At a global level, advocacy for digital transformation was bottom-up (56 per cent) rather than top-down (41 per cent). For Africa it was 34 per cent and 63 per cent, respectively. Top-down strategies were most pronounced in Europe (49 per cent) and Latin America and Caribbean (49 per cent), while Middle East led with bottom up approaches (70 per cent).

Approaches to digital transformation varied. Only 18 per cent of respondents globally, and 18 per cent in Africa, and 14 per cent each in Europe and Latin America and Caribbean, 21 per cent in Asia and Pacific, and 33 per cent in Middle East expected to continue doing the same things in their teaching and governance with technology. A larger proportion 43 per cent at the global level expected to do things differently with technology; for Africa the proportion was 16 per cent, Latin America and Caribbean led with 63 per cent, followed by Europe 53 per cent, Asia and Pacific 45 per cent, and Middle East 26 per cent. In Africa, 63 per cent were planning to do things differently but were limited by funds, while globally the figure was 38 per cent, and for Middle East 41 per cent, Europe 33 per cent, Asia and Pacific 32 per cent, and Latin America and Caribbean 23 per cent.

Digital transformation was integrated in institutional strategic plans in all the regions. According to the respondents, globally it was 75 per cent, ranging from 77 per cent for Africa, Asia and Pacific, to 76 per cent for Latin America and Caribbean, 74 Europe and 73 Middle East. Budget allocation for digital transformation was 55 per cent, from a high of 60 per cent in Africa to a low of 50 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean, with Middle East (56 per cent), Asia and Pacific (55 per cent), and Europe (51 per cent) in between. Overall, the bulk of the institutional budget allocated was mostly between 0 and 9 per cent (35 per cent) and 10 and 19 per cent (29 per cent). In most cases, 73 per cent of institutions reported having a senior person in charge of digital transformation. Training opportunities for faculty and staff were generally in the same range.

The survey further revealed regional divergences in online governance of student data and learning processes. Globally, 63 per cent of institutions reported managing enrolment and student data fully online, with a high of 72 per cent in Europe and a low of 55 per cent in Africa, and 70 per cent for Middle East, 60 per cent for Asia and Pacific, and 58 per cent for Latin America and Caribbean. But the use of learning management systems was lower. The range as reported by institutional leaders was from 47 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean to 24 per cent in Africa, while it was 40 per cent in Asia and Pacific, 34 per cent in Europe, and 33 per cent in Middle East. Online data management creates both new possibilities and perils in tracking and managing student enrolments, learning, and outcomes. This raises the issue of data privacy and protection. Globally, 55 per cent of institutions reported fully having ethical guidelines or data privacy policies. Africa ranked lowest at 43 per cent, compared to 65 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean, 64 per cent in Europe, 49 per cent in Asia and Pacific, and 41 per cent in Middle East.

Similarly varied was the use of technology and new modalities in teaching and learning. The global average for full integration of technology in teaching was 31 per cent. Africa ranked second to Middle East at 38 per cent and 40 per cent, respectively. The lowest was Latin America and the Caribbean at 11 per cent, followed by Asia and Pacific at 33 per cent, and Europe at 23 per cent per cent. When it comes to the full use of the new teaching modalities of flipped classroom, blended and online learning, Africa ranked last at 14 per cent, and Latin America and Caribbean on top at 49 per cent, while Asia and Pacific scored 32 per cent, Europe 24 per cent, and Middle East 22 per cent. The global average was 27 per cent. Very few of the responding institutions provided fully online courses: 32 per cent had none, in 14 per cent of institutions they comprised 1 to4 per cent of all courses, and in 13 per cent between 5 and9 per cent.

In much of the world the majority of undergraduate courses were largely delivered through lectures. Africa led in the category “mostly lecture-based learning but combined with problem-based learning”, scoring 56 per cent against a world average of 49 per cent, and ranked lowest under “mostly problem-based learning but combined with lectures” at 11 per cent compared to a world average of 19 per cent. Only 35 per cent of institutions globally reported having fully reconsidered the skills and competencies required of students in the past three years. The regional rankings were Latin America and Caribbean (56 per cent), Asia and Pacific (36 per cent), Europe (35 per cent), Africa (31 per cent), and Middle East (22 per cent). As for reviews of learning outcome assessments, the global average was 42 per cent, and was lowest in Africa at 33 per cent and highest in Latin America and Caribbean at 49 per cent.

Digital literacy is increasingly becoming a critical skill. However, the survey revealed relatively low levels of national support for digital literacy and computational thinking. The global average reporting “Yes, very much” was 19 per cent; Africa registered at the bottom with 12 per cent, while Asia and Pacific and Middle East were on top with 19 per cent each. At the institutional level, digital literacy was viewed as a transversal learning outcome in 22 per cent of the responding institutions globally, the same figure as Africa.

Equally low were levels of national support for open educational resources (OER). In terms of national initiatives in favour of OER, the global average for “Yes, very much” was 16 per cent, similar to Africa’s. The global average for support for online bibliography or library for online content was 23 per cent and for Africa 16 per cent compared to a high of 32 per cent each for Europe and Latin America and Caribbean. At the institutional level only 19 per cent reported fully creating and using OER at the global level, while in Africa 9 per cent did so, which was below the other regions. Commitment to open science was much lower at the national level (17 per cent) compared to the institutional level (56 per cent).

The impact of digital transformations on the nature of jobs and future of work is increasingly appreciated. As a result, continuous reskilling and upskilling through lifelong learning is becoming more and more imperative. Only 18 per cent of respondents globally agreed “Yes, very much” that there were national initiatives in support of lifelong learning; for Africa it was 16 per cent, Europe 24 per cent, Asia and Pacific 18 per cent, Middle East 14 per cent, and Latin America and Caribbean 8 per cent. At the institutional level, 84 per cent reported having adult learners globally led by Europe with 90 per cent, then Africa 88 per cent, Latin America and Caribbean 87 per cent, and Asia and Pacific and Middle East with 77 per cent each. African institutions reported a 65 per cent increase in adult learners over the past three years, compared to an average 55 per cent globally. African institutions also had higher expectations (68 per cent) that adult learners would increase than other regions (the global average was 61 per cent).

Overall, it is evident from the survey that digital transformation was being pushed by the leadership, followed by faculty, staff, students, governing board, and national authorities. The respondents identified the key achievements using new technologies as, in descending order, improved governance of information, new learning pedagogies to enhance the student experience, improved research, and improved accessibility to higher education. As for challenges, they selected financial costs, university culture’s slowness to adapt to change, lack of interest of faculty and staff to change, lack of capacity building, unreliable internet, and national policies, in that order. For Africa the order of challenges was listed as financial costs, unreliable internet, lack of capacity building, university culture, lack of faculty and staff interest, and national policies.

The report concluded by examining perceptions of current transformations. On institutional readiness towards change, the majority, 53 per cent, indicated they were “very ready”. Respondents from Africa were in the lead at 46 per cent, followed by Latin America and Caribbean 35 per cent, Asia and Pacific 33 per cent, Middle East 30 per cent, and Europe 21 per cent. African respondents (77 per cent) believed more strongly than others (global average 61 per cent) that digital transformation is necessary and inevitable in preparing students to actively participate in society. They also more strongly agreed that digital transformation exacerbates socioeconomic divides within and between countries by 35 per cent to 27 per cent.

Further, to 75 per cent globally, 89 per cent of African respondents strongly agreed compared that digital transformation and new technologies represent an opportunity to expand access to higher education. By a margin of 58 per cent to 39 per cent, they strongly believe these technologies will lower the costs of higher education; 97 per cent to 79 per cent strongly believe they are essential to improving higher education; 90 per cent to 77 per cent that they can enhance the quality of higher education; and 78 per cent to 58 per cent that higher education plays an important role in shaping digital transformation. Yet, only 27 per cent compared to 33 per cent globally believe their institutions were equipped for the future in terms of the emerging technologies and opportunities, compared to 40 per cent in Asia and Pacific, 35 per cent in Europe, 33 per cent in Latin America and Caribbean, and 30 per cent in Middle East.

Clearly, even before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic higher education institutions around the world including Africa were increasingly aware and committed to the challenges and opportunities of emerging technologies. They understood the need to undertake transformations at the national and institutional levels in terms of creating enabling policies, making the necessary financial investments in technological infrastructures and capacities, promoting institutional leadership, culture and commitment to change, providing opportunities for faculty and staff training and development. Further, it was appreciated that critical attention needed to be paid to the inequalities of access and the ethical dimensions of data protection and privacy in institutional data management.

COVID-19 acted as an accelerator in the digitalisation of higher education. It is evident from numerous reports in the higher education and popular media that following closures of campuses as part of the containment measures imposed by governments against the pandemic universities scrambled to transition to remote or distance teaching and learning using digital technologies. An informative comparative snapshot on how universities managed and continue to manage the massive disruptions engendered by COVID-19 is provided by the Association of Commonwealth Universities that conducted a survey in May 2020 of its 500 member universities across 50 countries around the world.

The transition to online education, research and administration revealed glaring digital divides among and within countries, as well as among and within universities in terms of digital capacities and access to data, devices, and broadband. More positively, it helped change perceptions about the quality of online teaching and learning. By the beginning of April 2020, higher education institutions had closed in 175 countries affecting over 220 million students. The survey showed 80 per cent of respondents reported teaching had moved online, 78 per cent agreed it had affected their ability to conduct research, while 69 per cent reported they had been able to take research activities online.

The digital divide between countries was evident in the fact that 83 per cent of respondents in the high income countries had access to broadband, compared to 63 per cent for upper middle income countries, 38 per cent in lower middle income countries and 19 per cent from low income countries. Institutions that were unable to move online were confined to the lower middle income countries (19 per cent) and low income countries (24 per cent). Only 33 per cent with broadband access strongly agreed that the pandemic had affected their ability to conduct research, compared to 43 per cent of respondents without broadband access.

Within institutions, the distribution of access to broadband ranged from 74 per cent for senior leaders to 52 per cent to those in professional services, to 38 per cent for academics, and 30 per cent for students. Institutional support for remote working in terms of devices or data was also skewed in favour of senior leaders and professional services staff (both 82 per cent), compared to students (45 per cent) and academics (40 per cent). Prior to the pandemic students were less likely than other groups to report always having worked online, while after the pandemic senior leaders were more likely than their counterparts to say they would work online frequently.

Perceptions of the quality of online teaching and learning showed marked improvement. The vast majority of respondents, 81 per cent, agreed that quality had improved since the pandemic; 90 per cent agreed that a blended degree, combining online and face-to-face learning, was equivalent to a degree earned only through face-to-face learning, while 53 per cent felt a degree earned solely through online learning was equivalent to one earned through face-to-face learning. As for online working, 65 per cent foresaw working online frequently after the pandemic, while 19 per cent foresaw doing so “all of the time”, and only 16 per cent said rarely and 1 per cent said never.

Fifty-three per cent of respondents envisaged all (26 per cent) or most (28 per cent) departments would continue to use online teaching and learning, and only 4 per cent said that no departments would do so. In terms of institutional commitments and capacity, 89 per cent agreed that their institution had the will to develop high-quality online teaching and learning, while 82 per cent of respondents agreed that their institution has the capacity to do so.

It was reported that universities were providing support for remote working, but with variations between countries and professional roles. Thirty-seven per cent noted their university made a contribution towards data costs, 31 per cent that they were provided device(s) and 7 per cent that their institutions contributed towards device costs. The levels of support ranged from 87 per cent in high income countries, to 70 per cent in upper middle income countries, 51 per cent in lower middle income countries, and 52 per cent in low income countries. Support was also provided in the form of faculty and staff training and development.

The most pressing challenges identified by respondents for remote working were internet speed (69 per cent), data costs (61 per cent), internet reliability (56 per cent), and time zones (38 per cent). Data costs were most pressing for those from low and lower middle income countries, while those from high income countries cited time zones. As for online teaching and learning, the leading challenges were accessibility for students (81 per cent), staff training and confidence (79 per cent), connectivity costs (76 per cent), and student engagement (71 per cent). Respondents from low and lower middle income countries emphasised connectivity costs, while those from high income countries stressed challenges relating to student perceptions of quality. In terms of impact on research, there were some disciplinary variations: in the natural, environmental and earth sciences 92 per cent of academics reported being affected, while in the arts, social sciences and humanities 61 per cent did so.

The twelve-point digital transformation agenda for Africa

Based on data collected from Africa, the ACU noted that African universities faced particular challenges in managing COVID-19. Many suffered from limited digital infrastructure, capacity and connectivity which made it difficult for them to transition online for education, research and administration. These challenges were compounded by enduring financial strains worsened by severe budget cuts as student enrolments dropped and government funding declined. Fundraising has largely been negligible in most African universities.

Also evident was the digital divide across and within African countries. Across the continent respondents identified many challenges including accessibility of students (83 per cent), staff training and confidence (82 per cent), and connectivity costs (89 per cent). In terms of devices and connectivity, respondents indicated 58 per cent had access to two devices, 82 per cent had access to mobile data and 35 per cent to broadband. In Kenya, 25 per cent of respondents reported having access to a desktop, while in Nigeria 15 per cent and in South Africa 13 per cent did. With regard to broadband, 63 per cent of South African respondents had access compared to 54 per cent for Kenya, and 27 per cent for Nigeria.

Among the leading challenges identified for remote working respondents across the continent were data costs (77 per cent), internet speed (71 per cent) and internet reliability (65 per cent). An encouraging development was the growing provision of institutional support. Forty per cent of respondents received contributions toward data costs from their university, 22 per cent were provided with a device and 8 per cent received a contribution toward device costs. Some institutions adopted innovative ameliorative measures, ranging from negotiating with technology companies zero-rated access or reduced subscription prices to educational content, to providing free dongles to students without remote connections.

There were of course national and intra-institutional variations. More likely to receive support were senior leaders and professional services than faculty and students. In terms of contributions to data costs, 62 per cent of senior leaders and 64 per cent of professional services received support. In the provision of devices 54 per cent of the former and 38 per cent of the latter received support.

As far as online teaching and learning is concerned, there was a marked shift. Prior to the pandemic only 16 per cent of respondents indicated online teaching had occurred in all or most departments; 74 per cent said that all or most teaching and learning was now online. Forty-seven per cent expected that all or most departments would continue to use online teaching and learning. Again, there were national divergences. In Nigeria 44 per cent of respondents reported no teaching and learning had moved online, unlike South Africa and Kenya where no respondents reported this to be the case. In South Africa 94 per cent of respondents stated all or most teaching was now online, compared to 62 per cent for Kenya and 22 per cent for Nigeria. Attitudes on the quality of online teaching and learning witnessed a marked shift as 80 per cent of respondents believed quality had improved; 49 per cent said they thought a degree earned exclusively online was equivalent, while 91 per cent agreed a blended degree is equivalent to a degree earned face to face.

African educators and policy makers now widely accept that the digital transformation of higher education is here to stay. They also appreciate more keenly the need to make significant investments and interventions in technology-based platforms for the higher education enterprise. In the context of the new realities and pressures, it is increasingly evident that the traditional instructional methods, modes of knowledge production and consumption, and institutional conceits of exclusivity are no longer tenable if higher education institutions are to remain relevant for Africa’s regeneration.

A report on digital transformation for British universities recommends ten useful guiding principles that promote digital fluency among faculty and students: institutional digital innovation and progress; integrated working by creating inclusive and collaborative working environments; engaged learning by rethinking interactivity across physical and virtual spaces; personalised learning that motivates and facilitates individual student success; transformed learning spaces that are connected, coherent and compelling; inclusivity in design to accommodate diverse students and learning styles; building of learning communities for students that are safe, secure, and empowering; learning infrastructure in a propitious technology environment that allows for continuous upgrading; and innovative learning based on continuous experimentation, learning, and investment.

Higher education will emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic profoundly changed from the most catastrophic crisis it has ever faced and for which it was not prepared. The EDUCAUSE 2021 Top IT Issues foresees the emergence of what it calls alternative and overlapping futures involving three scenarios, restore, evolve, and transform. “The Restore scenario is a story of institutional survival focused on reclaiming the institution’s pre-pandemic financial health”, while the Evolve scenario applies to “institutions that will choose to incorporate the impact and lessons of the pandemic into their culture and vision”. Institutions embracing the Transform scenario “plan to use the pandemic to launch or accelerate an institutional transformation agenda”.

African educators and policy makers now widely accept that the digital transformation of higher education is here to stay.

For example, on the issue of financial health, the Restore scenario focuses on cutting costs, while the Evolve scenario focuses on “increasing revenues and funding sources and on evolving the institution’s business model”. On online learning, the “Restore version takes a structural approach to online learning—emphasizing supports, processes, and policies—whereas the Evolve version focuses on advancing the quality of online learning”. On information security the “Restore version is a tactical one that covers returning to campus as well as cost-effectiveness and recovery. The Evolve version takes a strategic approach and also expands the scope of cybersecurity efforts to include off-campus locations, in recognition of the need to adapt to constituents whose technology environments will never fully return to campus”.

For its part, the “Transform version expands the role of technology (digital transformation) in order to not only reduce costs but also maximize value”. Transform institutions seek to prioritise changing institutional culture and promoting technology alignment. They also seek to develop “an enterprise architecture to enable business outcomes, manage data to enable decision-making and future opportunities, streamline business processes, and enable digital resources to keep pace with strategic change”. For enrollment and recruitment they endeavour to explore and implement “creative holistic solutions for recruitment, including analytics-based marketing around student career outcomes, technology-enabled transfer agreements and partnerships, and use of social media to build student communities”.

Each African university has to ask itself: What kind of institution does it wish to become in the post-COVID-19 era? Many of course will combine elements of all three—restoration, evolution, and transformation. Some may not survive, while others will thrive. Those that endure and excel will need to adopt the twelve-point agenda outlined below.

First, COVID-19-induced transition to remote delivery of education must turn to the development of a long-term digital strategic framework that ensures resilience, flexibility, experimentation, and continuous improvement. Digital transformation must be embedded in institutional culture from strategic planning processes, organisational structures, to administrative practices and daily operations while avoiding exacerbating existing inter- and intra-institutional inequalities for historically, socially, and spatially disadvantaged communities. Universities have to integrate digitalisation in their four core missions: teaching and learning, research and scholarship, public service and engagement, and innovation and entrepreneurship.

Second, universities have no choice but to make strategic and sustainable investments in digital infrastructures and platforms by rethinking capital expenditures and increasing spending on technological and digital infrastructure. Their budgets must not only support a more robust online learning ecosystem, but also build in flexibilities to reallocate resources in the face of unexpected crises. Critical in this regard is building resilient and secure digital business continuity plans, strategies and capabilities.

Third, African universities have to develop online design competencies both individually and through consortia with each other and overseas institutions that are committed to mutually beneficial partnerships in promoting e-learning. Such consortial arrangements should encompass sharing technical expertise for online instructional design, pedagogy and curation, content development, and training of faculty and university leaders. Inter-institutional collaboration is more imperative than ever following the global transition to online teaching and learning spawned by COVID-19 because competition for students between universities in the global North and the global South is likely to intensify. Africa already loses many of its richest and brightest students to universities in the global North and increasingly the major emerging economies of Asia. Now, they stand to lose some middle class students who can afford enrolling in online programmes offered by foreign universities that enjoy better brands than local universities.

Fourth, universities need to entrench technology-mediated modalities of teaching and learning. Higher education has to embrace face-to-face, blended and online teaching and learning, and raise the digital skills of faculty and students accordingly. Digital transformation promises to diversify students beyond the 18-24 age cohort, maximise learning opportunities for students, and open new markets and increasing tuition revenues for universities. Blended and online teaching and learning offers much needed flexibility for students, who increasingly find it appealing and convenient for its space and time shifting possibilities. It also offers faculty “opportunities to improve educational outcomes by adopting a wider range of learning activities, allowing greater flexibility of study times, space for reflection and a move to different forms of assessment”.

Fifth, digitalisation provides opportunities for beneficial pedagogical changes in terms of curricula design and delivery that involves students and incorporates how they learn. It helps faculty to rethink learning and teaching practices, to see themselves less as imperious sages on the stage and more as facilitating coaches. In this transformed pedagogical terrain and relationship, universities ought to “ensure their professional development strategies and plans include digital training, peer support mechanisms, and reward and recognition incentives to encourage upskilling”. An important part of this agenda is for universities to promote research that enables them to stay current with the changing digital preferences, expectations, and capabilities of students, faculty and professional staff.

Sixth, universities should develop curricula that impart skills for the jobs of the 21st century. Such curricula must be holistic and integrate the classroom, campus, and community as learning spaces; promote inclusive, innovative, intersectional, and interdisciplinary teaching and learning; embed experiential, active, work-based, personalised, and competence-based learning; instil among the GenZ youth the mind-sets of creativity, enterprise, innovation, problem solving, resilience, and patience rather than mindsets of passive learners and knowledge consumers who regurgitate information to pass exams. The extensive changes taking place require continuous reskilling, upskilling, and lifelong learning. The growing importance of careers in science, technology, engineering, healthcare, and the creative arts, all within an increasingly technologically-driven environment, necessitates the development of hybrid hard and soft skills.

Seventh, for student success, universities have a responsibility to embrace and use educational technologies that support the whole student. According to the EDUCAUSE 2020 Student Technology Report, student success goes beyond degree completion. Holistic support encompasses “access to advisors and to helpful advising technologies”, raising students’ awareness about “the tools available to students, where to find those tools, how to use them, and how they can help advance educational and career goals”. Surveys show students also appreciate course-related alerts, nudges and kudos that are positive and offered early. Regular, constructive, targeted and personalised feedback makes a big difference, so does “embedding a human assistant in the online virtual lectures and office hours [who] . . . through modeling, or observational learning, may persuade students to imitate the assistant . . .. The assistant could be a graduate teaching assistant, an undergraduate student, or a peer leader”.

On technology use and preferences, it is important for universities to “establish research-based instructional practices in all teaching modalities” and develop “an acceptable use policy (AUP) for classroom uses of student devices that is informed by evidence-based practice and students’ preferences for device use. Allow students to participate in the design of the AUP to create a digital learning environment in which they feel empowered to use their devices and to regulate their own behavior”. Also important is assessing “student access to Wi-Fi and digital devices and work to ensure that every student has access to these critical technologies”.

Eighth, universities need to develop effective policies and interventions to address the digital divide and issues of mental health disorders and learning disabilities. Resources and new investments are required to provide opportunities to those trapped by digital poverty. An inclusive agenda for digital transformation must also include using the universal design for learning framework (UDL) “when designing learning experiences and services to optimize learning for all people… If technology and IT policies are thoughtfully and inclusively incorporated into a course guided by UDL, then ideally learner variability, choice, and agency increase, while the need for individual accommodations is greatly reduced”.

Creating inclusive learning environments also entails investing in professional development for faculty to better prepare them to provide accessible instruction. Moreover, as universities seek to expand access to mental health services, they need to leverage technology-based interventions that do not just introduce new ways of offering services but also enable scaling of those services to multiple students online.

Ninth, as learning and student life move seamlessly across digital, physical, and social experiences, issues of data protection and privacy become more pressing than ever. Protecting personal data especially relating to students has to be a priority through the provision of safe storage options and the development of policies and practices that are transparent and ethical. Students are generally comfortable with the institutional use of their personal data as long as it helps them achieve their own academic goals, but not for other gratuitous purposes. Thus, they need to know and have confidence in how the institution collects, stores, protects and uses their personal data, and be able to view, update, and opt out.

The proliferation of online harassment especially against women and people from marginalised groups requires institutional protections including creating codes of conduct against clearly defined online harassment, fostering an anti-harassment culture, and developing a centralised system of reporting and tracking. Growing dependence on digital technologies increases cyber security risks that require robust mitigation capabilities including conducting information security awareness campaigns.

Tenth, in so far as the market for online programmes is transnational, it is essential for universities to pay special attention to international students who face unique barriers in an online learning environment that require special redress. Generally, African universities are not serious players in the international education market. Online education opens new opportunities. The key barriers international students face in the virtual classroom include time differences, hard deadlines, limited connectivity and access, lack of learning space, lack of scheduled support, lack of language support for non-native or secondary speakers of the language of instruction, remote class culture, invisible support, social isolation and racial discrimination.

The solutions include adopting asynchronous learning, allowing flexible timelines, providing connectivity support, offering safe learning spaces, replicating the class structure, providing language support, setting digital expectations early, building cultural bridges, providing remote support services, and practicing micro-inclusions by encouraging “teachers, staff and students to use subtle, inclusive ways to show international students they are welcome and valued” and establishing safe “virtual” spaces for international and marginalised students and faculty to talk openly.

Eleventh, higher education institutions must develop meaningful partnerships with external constituencies and stakeholders including digital technology and telecommunication companies. As the demands for return on investment increase from students and their families, as well as the state and society, pressures are growing on universities to demonstrate their value proposition and social impact. This translates into the question of graduate employability, closing the much-bemoaned mismatches between educational qualifications and the economy. This entails strengthening experiential learning and work-based learning, which requires strengthening connections with employers. Virtual learning not only necessitates and opens new ways of engaging industry, the economy and society, it also creates huge demands for digital skills for the emerging jobs of the 21st century.

Higher education institutions must develop meaningful partnerships with external constituencies and stakeholders including digital technology and telecommunication companies.

Twelfth, the stakes for research have been raised for African higher education institutions. All along they have been expected to actively produce both basic and applied research and generate innovations that address the pressing problems of African communities, countries, continent, and Africa’s place in the world. However, levels of research productivity have remained generally low. Universities also have a responsibility to promote research and data driven policy and decision-making. Following the disruptions and digital opportunities engendered by COVID-19, universities will increasingly be expected to anchor their research and innovation in the technological infrastructure that supports and enhances the opportunities of the Fourth Industrial Revolution for Africa.

Research, innovation and technological infrastructure

As noted earlier, the Fourth Industrial Revolution is disrupting and transforming every sector. A critical facet of the technological revolution is advancing research and turning hindsight into insight to make our world a better place whether its gene sequencing, predictive medicine, climate research, economic modelling, manufacturing with computer aided design or financial services trading and risk management.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) has produced numerous reports showing how the data-driven technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution are shaping the future of advanced manufacturing and production; consumer industries; energy, materials and infrastructure; financial and monetary systems; health and healthcare; investing; media, entertainment and sport; mobility through the creation of autonomous vehicles; and trade and global economic interdependence.

In its report, The Future Jobs Report 2020, the WEF forecasts massive changes in the jobs landscape by as soon as 2025. The report contends, “we estimate that by 2025, 85 million jobs may be displaced by a shift in the division of labour between humans and machines, while 97 million new roles may emerge that are more adapted to the new division of labour between humans, machines and algorithms, across the 15 industries and 26 economies covered by the report”. It identifies the top ten emerging jobs as: Data Analysts and Scientists, Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Specialists, Big Data Specialists, Digital Marketing and Strategy Specialists, Process Automation Specialists, Business Development Professionals, Digital Transformation Specialists, Information Security Analysts, Software and Applications Developers, and Internet of Things Specialists, in that order.

Conversely, the top ten declining jobs mentioned are: Data Entry Clerks, Administrative and Executive Secretaries, Accounting, Bookkeeping and Payroll Clerks, Accountants and Auditors, Assembly and Factory Workers, Business Services and Administration Managers, Client Information and Customer Service Workers, General and Operations Managers, Mechanics and Machinery Repairers, Material-Recording and Stock-Keeping Clerks.

“Data is the new oil” headlines abound and countries that can harness this data to extract value will have a significant competitive advantage. Data is even more valuable than oil, whose reserves on the planet are fixed. As Adam Schlosser notes, “Unlike oil, increasing amounts of data are being generated at a pace that’s hard to fathom: in the next two years, 40 zettabytes of data will be created – an amount so large that there is no useful framing exercise to demonstrate its size and scope. It’s roughly equivalent to 4 million years of HD video or five billion Libraries of Congress . . .. Unlike oil, the value of data doesn’t grow by merely accumulating more. It is the insights generated through analytics and combinations of different data sets that generate the real value.”

Thus, harnessing data, advancing research and drawing insights requires advances in computing and specifically High Performance Computing or HPC. There is an intersection between technologies that are driven by the pertinent needs of the 21st century workplaces such as Machine Learning, Artificial Intelligence, Big Data etc. and high performance computing. Huge technological strides in the development of hardware technology and computing architectures have played a big role towards making it possible for complex machine learning algorithms to be used to resolve real world problems and challenges from climate change to disease pandemics.

It is noteworthy that the future jobs mentioned above in areas such as Data Analytics, Big Data, Artificial Intelligence and Robotics will require advanced computing technologies and performance in order to support the operational roles that employees will play in organisations. Notwithstanding the financial pressures that the COVID-19 pandemic has visited on Africa, the continent has to make strategic and smart investments in the digitalisation of its economies, societies, and educational institutions. At most it has a decade to do so if it is not to be permanently left behind by the rest of the world.

During the First Industrial Revolution of the late 18th century Africa was reduced to providing labour for the Atlantic Slave Trade that developed EuroAmerica and underdeveloped the continent. Under the Second Industrial Revolution of the late 19th century, colonised Africa supplied raw materials that deepened its dependency. Africa participated in the Third Industrial Revolution of the late-20th century as a collection of neo-colonial peripheries. In exchange for its labour Africa received trinkets, its raw materials fetched a pittance on world markets, and later the backward post-colonies were sold “appropriate technologies”. Now, the continent is even paying dearly for the privilege of exporting its data!

The danger of remaining peripheral to the Fourth Industrial Revolution for Africa is not exploitation and marginalisation, but historical irrelevance as noted earlier, becoming a landmass of disposable people. Critics caution that Africa should not embrace the Fourth Industrial Revolution at the risk of “premature de-industrialisation”. Others warn of the dangers of data manipulation and cyberattacks and that the continent is not ready, an argument that condemns Africa to eternal technological underdevelopment. On the contrary, as Ndung’u and Signé, argue, the transformative potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution for Africa is substantial. It promises to promote economic growth and structural transformation; fight poverty and inequality; reinvent labour skills and production; increase financial services and investment; modernise agriculture and agro-industries; and improve health care and human capital.

In order to play a pivotal role in the 4th Industrial revolution, African higher education institutions need a change of mind set and to recognise their role as centres for teaching and learning, research, knowledge and technology transfer to current and future generations. They need to collaborate among themselves and with industry, government and other key players to undertake research, innovation, and develop digital technologies that address the continent’s most enduring and difficult needs and opportunities, not simply consume technologies produced by others.

The danger of remaining peripheral to the Fourth Industrial Revolution for Africa is not exploitation and marginalisation, but historical irrelevance.

Africa’s leading research universities need to reinvent themselves by using advanced technologies such as HPC that support supply of human resources for the jobs of the future, as well as training faculty that have the requisite skills and competency to equip students with the skills required to take up those jobs. The digital transformation agenda has huge implications on universities’ institutional capacities, financial resources, human capital in relation to development and delivery of curricula and technological infrastructures. Currently, the continent’s HPC capacity is abysmally low as shown below.

Data presented at the HPC conference held at USIU-Africa and the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) in December 2017 underscored Africa’s insignificant capability for the high performance computing that is essential for the digital revolution as evident in Figure 2.

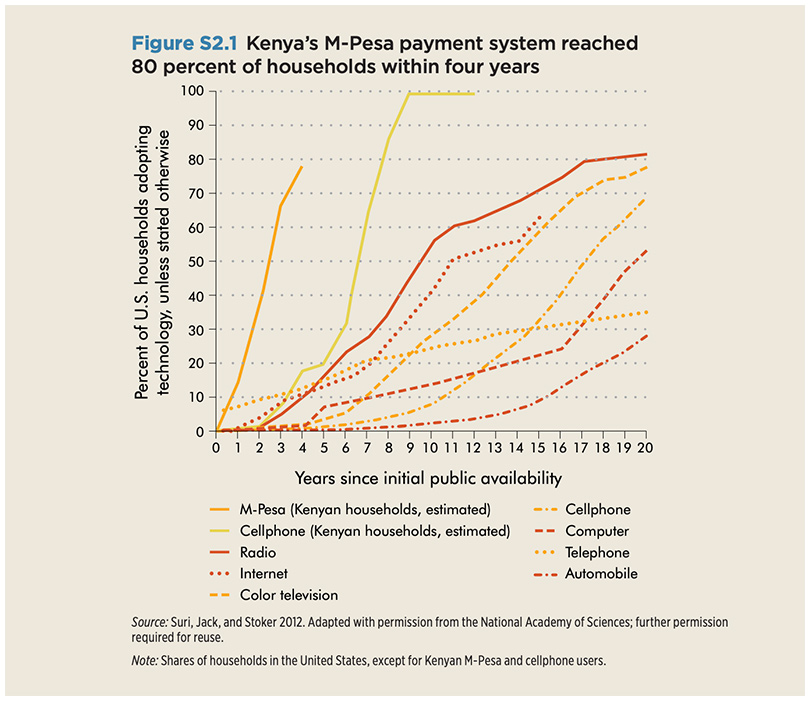

The need and rationale for HPC in Africa is self-evident. It is simply unacceptable for a continent of 1.2 billion people to have negligible HPC capacity that is so essential for research, innovation and development. The African continent faces several socio-economic and political challenges, scores low on research and innovation indices, and is plagued by the persistent challenges of “brain drain” with some of the best and brightest people often leaving the continent in search of “greener pastures” including access to research infrastructures, higher pay and an appreciation for innovation. Nevertheless, Africa is posting impressive economic growth rates and has one of the youngest populations in the world. Technology is making a dramatic impact in Africa and Africa’s rate of technology adoption is unprecedented as evident in Figure 5. The mobile phone and internet are increasingly widely available.

For Africa to competitively contribute to research and innovation and to find home-grown solutions to its socio-economic challenges, it is important that measures are taken which will provide the continent with access to cutting-edge computing technologies from hardware to software that have become essential for research, innovation, growth and jobs. Africa must invest in High Performance Computing platforms because modern scientific discovery involves very high computing power and the capability to deal with massive volumes of data. Otherwise, the continent will miss out on major advances in research and innovation in the digital age.

It is estimated that a $1 HPC Investment on average yields $463 in revenue and $44 in added profit. HPC can help solve Africa’s challenges, such as:

- Climate Change: climate research and weather prediction are critical if Africa is to weather the ravages of climate change. Predicting weather accurately can enable countries to make better long-term food security policies, environmental policies and interventions and even security policies.

- Health and life sciences: gene sequencing, molecular research and bio-physical simulations can all support the development of effective medicine and vaccines for critical diseases like Malaria and HIV in Africa; and explore Africa’s abundance of natural remedies. Epidemic modelling can predict disease spread so that governments and healthcare providers can make appropriate interventions.

- Oil, gas and mineral exploration: Africa has an abundance of natural resources and access to HPC platforms can speed up seismic analysis which can speed up exploration and exploitation.

- Growth of industry and SMEs: Industry and SMEs are increasingly dependent on the power of supercomputers to discover innovative solutions, cut costs and reduce time to market for products and services (European Commission, 2017). Sectors such as retail, manufacturing and financial services could benefit from HPC for data analysis for insights and innovation.

- Economic research: economic modelling using big and open data would lead to insights and contribute to evidence-based policy making.

- Research Collaboration: Increase research collaboration between Africa and other parts of the world. Having local capacity for large data processing means African scientists can better contribute to the global research agenda, provide tools for wider collaboration with research colleagues, and stimulate increased awareness, utilisation and application of high performance computing in the sectors identified in Figure 1 above.

It is evident from Figure 1 and Figure 2 above that despite the potential that HPC for promoting collaborative research and innovation in various sectors of the world economy, hardly any effort has been made towards harnessing this huge potential on the African continent. There have been HPC initiatives in several countries in the past, including Ghana, Kenya, Congo, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Cameroon. Clearly, these efforts have not gone far.

There is need to develop HPC technical design and management skills etc., leverage initiatives and build synergy through discussions with potential partners including research programmes, networks and institutions, university communities, associations and institutions, donors, development partners, and philanthropists, governments, intergovernmental agencies, and the private sector.

It is simply unacceptable for a continent of 1.2 billion people to have negligible HPC capacity that is so essential for research, innovation and development.

To conclude, building digital capacities including information literacy for students at one end and HPC infrastructures at the other end is essential for dealing with the development and employment challenges of today, tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow. Digital capabilities and skills are not good to have, but are a must-have. They are essential to support effective development of solutions to address societal/scientific/industrial challenges in Africa, and the development of innovations, products and services.

This will lead to job creation; building computing capacity that will create new opportunities for both scientific applications and computing technologies; support for growth and competitiveness in industry and Africa’s economy through round-the-clock availability and utilisation of HPC systems and services; and enhance South-South and South-North collaboration in education, research and development.

We invite you to join African universities in this great calling and journey to transform higher education on this continent to educate, skill, and empower the youth to fully participate in their countries’ socioeconomic development. At stake is not only their future, but the future of the African continent and humanity itself, as much of this humanity becomes increasingly African.