By now you have heard and read acres of text discussing and dissecting Eliud Kipchoge’s epic performance as the first human to run a marathon distance in under 2 hours at the incredible pace of 1:59:40. Much of the analysis from the foreign press comes with the rider: great athlete but it was not a record-eligible marathon.

The purists point fingers at Eliud’s turbocharged shoes (the Nike Vaporfly Next%), the rotating cast of 41 pacers, a powered carb drink dispensed with precision, the pace car with a laser system as an additional wind breaker, the flat course and the emotional spin of a humble hero, tugging hearts in a compelling story of courage. There were undertones of culturally reductive theories that profile elite Kenyan runners as being forged from the desire to distance themselves from their poverty by running great distances to school – the single story of all great Kenyan athletes.

The outsized PR of the INEOS 1:59 was bound to be a niggling point for the detractors. The title sponsor, the petrochemical business empire that is INEOS and its majority shareholder, Jim Radcliffe, are accused by some of moving their headquarters to Switzerland to avoid paying UK taxes. Critics point to INEOS’s chequered environmental track record in Europe and recent fracking controversies as INEOS flexes muscle in the fossil fuel space in the UK.

For us, his country folk, the Kenyans, it was an ecstatic moment. A once in a lifetime spectacle. I spoke to friends and family who had all reserved Saturday morning to watch Eliud Kipchoge race against the clock and his own limits and many compared it to the euphoric moment in November 2008 when Barack Obama beat Republican Senator John McCain to become the first black president-elect of America. Eliud had cemented his iconic status as a Kenyan hero. In the midst of the despondency with the national state of affairs, the record in Vienna provided a fleeting moment of patriotic fervour.

On the chilly evening of 12th October, I made my way to the VIP reception in honour of the greatest marathoner of our age, hosted at the finish line in the historic Prater park, in Vienna. I battled in my head, trying to articulate what I had witnessed that morning. In a different time and age, this event would have been described as miraculous. 8 hours earlier, I had witnessed how the simple act of running could achieve transcendental importance. The Prater Hauptalee, stretching 4.3 kms, thronged by an estimated 120,000 fans in the morning, was now empty. The only indicator of the event were the barricades stretching down the straight road lined by chestnut trees with yellow leaves.

The city of Vienna had a date with destiny that Saturday autumn morning in October. From the Praterstern train station, one walks past the Vienna Athletic Centre, located about 200 metres from the finish line where Eliud made history.

All agreed that Eliud Kipchoge had cemented his iconic status as a Kenyan hero. In the midst of the despondency that had settled among Kenyans, the record in Vienna provided a fleeting moment of patriotic fervour.

Behind those stadium walls, another Kenyan had set the pace for Eliud Kipchoge six years before he was born. In 1978, the incredible Henry Rono smashed the world 10,000m record in Vienna on his way to the unparalleled achievement of 4 world records (10 000m, 5000m, 3000m and the 3000m steeplechase) in a span of 81 days. Henry Rono was paced by a Dutchman, Jos Hermens, the former athlete-turned-sports management don and founder of Global Sports Communication that manages Eliud Kipchoge.

Vienna was also the birthplace of renowned Austrian athletics coach Franz Stampfl, who coached Roger Bannister for the world’s first sub four-minute mile, the man who would inspire Eliud’s sub 2 marathon attempt.

The venue of the VIP after-party comprised a series of enclosed white tents adjacent to the finish line. Suited bouncers manned the entrance and a DJ livened up the evening. The Kenyan Deputy President William Ruto, was in attendance and in conversation with politician Njeru Githae, the newly appointed ambassador to Austria. Moments after the morning event, I had spotted the Deputy President with an entourage, perhaps on a solidarity run for Kipchoge, jogging down the road past the Vienna Athletic Centre, prominent in team Kenya colours. The irony of the moment was not lost on #KOT (Kenyans on Twitter).

Henry Rono was paced by a Dutchman, Jos Hermens, the former athlete-turned-sports management don and founder of Global Sports Communication that manages Eliud Kipchoge.

Eliud arrived in his classic understated manner, making his way from the back to the front without a fuss, pumping hands along the way and charging the energy in the gathering to fever pitch. He was indeed the happiest man that day and you could see the joy on his face after those many months of anticipation and meticulous planning. Catching his physio Peter Nduhia on the sidelines, he recapped the tension in the engine room leading up to the main event.

On the afternoon of 11th October, Eliud complained of muscle strain after rising from a sitting position on a slack sofa. Luckily, it proved to be nothing threatening but is frightening to imagine that the entire attempt would have been sabotaged by the cushioning of a couch.

The speeches commenced with a word from the organisers and the CEO of INEOS, Jim Radcliffe, reiterating that a billion people in the world had recognised that something incredible happened in Vienna. Then Eliud took the stage. As he stepped onto the raised platform, the audience burst into a thunderous cheer. He cut a diminutive figure in a fitting black tracksuit. When he started to speak, the audience fell into complete silence, hanging onto his every word. Several phones were in the air recording video.

Eliud graciously dished out his rounds of thanks to everyone involved in the success of the event, with emphasis on the 41 pacemakers, acknowledging the power of collaboration, sharing the moment and settled into his core message:

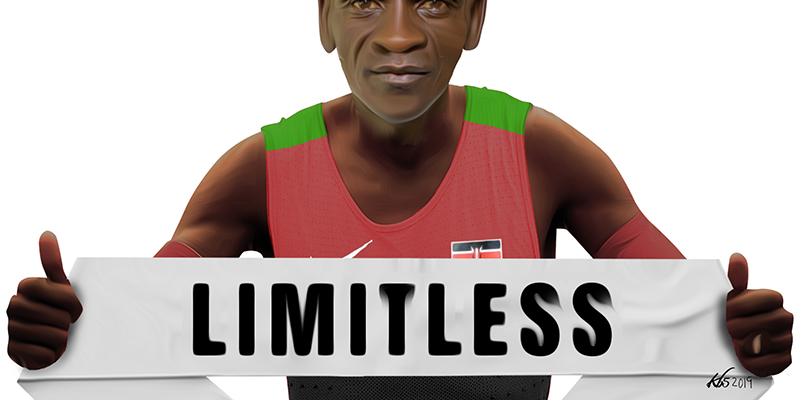

“I always say no human is limited. I hope the limitations from today will not appear anywhere in this world. I am the first and I trust that in the near future, more athletes will run under two hours.”

Of the many references made of Eliud’s sub 2 marathon history-making feat, from Neil Amstrong’s moon landing in 1969 to Edmund Hilary and Tenzing Norgay’s climbing the summit of Mount Everest in 1953, it is Sir Roger Bannister’s 4-minute mile record that Eliud has referenced consistently.

Eliud alluded to the story of the Englishman Roger Bannister who in 1954 ran a mile in under 4 minutes and broke an athletic barrier hyped as an impossible feat by journalists of the day. He mentioned this event when he revealed that experts had stated that the sub 2 hour marathon barrier would be unbreakable until around 2075.

A man’s heroes can offer a window into his own motivations.

Sir Roger Bannister (died March 3, 2018) was the first man to run one mile in under 4 minutes at 3:59:4. Comparatively, the 1 mile to the 26.2 miles ( 42 km) is world’s apart even in the categories of distance running. What is similar between these two men six decades apart is their grit. Bannister, like Eliud, had made an attempt on the record coming close and building the confidence required for a sub record attempt. Both men made the record attempts in what were managed speed trial events with pacesetters. Both men set out to make sporting history, and did.

No pain, no gain

Eliud’s daring and consistency in performance has raised his profile to global iconic status. He has achieved greatness as an exceptional athlete and a gracious individual. His work ethic and discipline is admired by sportswriters. There are YouTube videos analysing his running efficiency and form.

Fellow athletes marvel at his ability to maintain composure under great physical strain. It is that pain management that sets Eliud apart even within the elite ranks.

Endurance is a measure of high pain tolerance and Eliud is known for his ability to rise beyond pain, which is characterised by his signature smile in the heat of battle. Olympian Bernard Lagat, second only to Hicham El Guerrouj as the fastest 1500m runner of all time, looks up to Eliud as an inspiration. Lagat, who is Eliud’s senior, has been a collaborator on the sub 2 challenge, featuring as a pacesetter during the Breaking 2 Nike attempt in Monza, Italy. He featured twice as a pacemaker during the 1:59 challenge, and he put it plainly:

“It doesn’t matter who you are, at some point you will feel the pain.”

Peter Nduhiu, Eliud’s physio for 16 years, continues to marvel at Eliud’s ability to block pain and suspend it until the end of business. To endure the pain, one returns to the core tenet of Eliud’s training regime:

“With perfect preparation you can handle any pressure.”

After 10 marathons under 2:05 and a world record set in Berlin, Eliud had already traveled beyond previously set limits. It has been a long career of over 15 years of steady progress towards this mark.

For those who know Eliud, the record was never in doubt. His teammates, men such as Geoffrey Kamworor, the half marathon world record holder and Olympian Augustine Choge debated whether he would run a high or low 1: 59.

Eliud’s notoriety is single-minded focus and unwavering commitment to his goals. Alex Korio, one of the many pacesetters during the challenge, admired Eliud’s ability to be absolutely free of distraction. In Eliud’s own words,

“ Don’t make excuses. When you decide to do something, do it. Self-discipline is a lifestyle. Only the disciplined ones are free in life”.

He is a sought-after sports celebrity known for his motivational speeches and clear insights where he discusses running as a metaphor for principled living and a matter that involves not just one’s legs but also the state of one’s heart and mind.

James Baldwin, sharing advice on writing that applies equally across life noted:

“Talent is insignificant. I know a lot of talented ruins. Beyond talent lie all the usual words: discipline, love, luck, but, most of all, endurance.”

The way of the elite athlete is one of dedication and commitment to a monastic routine. This is now the common feature of the Kenyan athletes’ creed. It is the philosophy of the training camp: hard work, good form and teamwork.

Eliud has been a good ambassador for the marathon and a timely hero in a country where people also smile through their pains. He has the charisma and likeability of Liverpool football manager Jurgen Klopp, a man who is hard to hate.

Eliud’s notoriety is single-minded focus and unwavering commitment to his goals. He is a sought-after sports celebrity known for his measured speech and clear insights where he discusses running as a metaphor for principled living.

1: 59 becomes a symbolic number in the ranks of Roger Bannister’s 4-minute mile and as a source of inspiration. True to that spirit, a day after Eliud’s achievement on the 13th of October, Kenyan athletes swept the Chicago marathon in both male and female categories. Lawrence Cherono broke away from a three-way battle to sprint to victory in the final mile and Brigid Kosgei smashed Paula Radcliffe 16-year-old marathon record. It is worth noting that Eliud’s first World Marathon Major was in Chicago in 2014.

A nation of champions

Eliud Kipchoge stands on the shoulders of his predecessors and he has taken the sport to unprecedented heights as the Tiger Woods of the marathon. However, his story is the culmination of three decades of marathon progression in Kenya. If Eliud has traveled far, it is because he built on the successes and failures of those who came before him.

Today, Kenya’s marathon talent runs so deep that the only athletes who make it to national prominence are world record holders and Olympic gold medalists. Every weekend somewhere in the world, there is Kenyan winning a marathon. Vincent Kipchumba, who won the Vienna marathon in April (2019) and the Amsterdam marathon a week after Eliud’s challenge would only be recognised by seasoned sports journalists. Indeed, before his world record feat in 2018, Eliud’s face was not even instantly recognisable in Eldoret, the hometown of the champions.

An excerpt from In Running with Kenyans by Adharanand Finn, tells the story of the phenomenal emergence of Kenyan running talent in the marathon.

“In 1975, no Kenyan had run a marathon time below 2hrs 20 minutes, compared to a time accomplished by 23 British runners and 34 US athletes. By 2005, only 12 Britons and 34 US runners had done a sub 2: 20 compared to 490 Kenyans.”

It is also easy to forget that Kenya only started to appear as a contender in the marathon as recently as 1987. The Japan-based Douglas Wakiihuri brought in the first gold medal at the world championships in Rome in 1987 and the Olympic silver in Seoul, South Korea in 1988. He was also the first Kenyan to win the London marathon in 1989.

The Olympic gold eluded Kenyans for another two decades. Many came close. Erick Wanaina with the bronze in 1996 in Atlanta followed by another bronze by Joyce Chepchumba in Sydney 2000.

In 2003, the year that Eliud’s career started to show promise with a gold in the World Championships in 5000m in Paris, another phenomenal Kenyan athlete, Paul Tergat, who switched from a successful career on track to marathon greatness, broke the world record in Berlin.

Paul Tergat was the first Kenyan to hold a marathon world record and the first man to run a sub 2:05 time. Tergat in my books was the greatest distance runner of his generation and he carried himself with a level of grace and humility that is epitomized in Eliud’s celebrity today. The following year, the sensational Catherine Ndereba brought home the first female silver in Athens 2004. Eliud Kipchoge won a bronze in 5000m final in those games.

In 2008, Japan-based Samuel Wanjiru, following in Wakiihuri’s footsteps became Kenya’s first Olympic gold medalist in the marathon in Beijing and set an Olympic record. The phenomenal Samuel Wanjiru went on to win the London marathon in 2009 and the Chicago marathon in 2010, two years before Eliud switched to road racing.

Tergat who was the original king of the roads believed that even the greatest runners in the marathon had their limits. When Wilson Kipsang lowered the mark in 2013 to 2:03:23, Tergat, watching victory in Berlin, had stated that he did not envision a sub 2: 03 marathon in his lifetime:

“Take it from me today; forget about it, it will never happen. It’s impossible”.

A year later, in 2014, Dennis Kimetto, took it under 2 hours 3 minutes, and Eliud Kipchoge lowered it further to its current mark at 2:01:39 in 2018. If the history of Kenyan performance in the marathon teaches us anything, it is that limits are to be challenged.

A good career is marked by one’s ability to meet challenges against the odds and rise beyond the established limits of the chosen discipline. However, even moments of greatness in life are fleeting. Like the rise and fall of legendary Henry Rono, ultimately an athlete’s career is a short episode in the span of a lifetime. There a dozen or so athletes who have run a sub 2.05, but only two have run a sub 2.02. One is Eliud Kipchoge and the other is his greatest rival Kenenisa Bekele who missed the world record by two seconds ( 2:01:41) in Berlin this year.

The phenomenal Samuel Wanjiru was Kenya’s first Olympic gold medalist in the marathon. He won the London marathon in 2009 and Chicago in 2010, two years before Eliud switched to road racing.

Eliud still has it in his tank to lower the world record in a World Major given his INEOS 1:59 confidence boost and to wrap up his incredible career run with a second Olympic gold in Tokyo in 2020.

His brand of humility amidst all the hype around his accomplishments has endeared him to the growing hordes of fans globally. (There were 11 billion impressions on Twitter during the 1:59 challenge.)

Humility is a core part of the Eliud Kipchoge brand and something his coach of 18 years, Patrick Sang, consistently echoes as a foundational principle behind his success.

“Life is not about stardom,” says Sang. He reassures that Eliud is not just a great athlete, he is also a great human being, inspiring in all aspects of his life outside his profession. Sang admits that in the last three years, he has moved from being Eliud’s role model and teacher, to now what he feels is the humble position as his student.

I prod him for the significance of the moment, and after a short pause in reflection, he wraps it down to a one-liner, “We implemented the belief”, leaving me ruminating on how far one can broaden their horizons with mental fortitude. Beyond the inspiration of Eliud’s transformational message #nohumanislimited lies the subtext of excellence which is not just belief but also execution.