China’s growing global dominance got a publicity boost this April 2019 with the latest Forum on Belt and Road International ( BRI) Cooperation. The annual event brought world leaders from 37 countries, 5000 delegates from 150 nations and representatives of 90 international organisations to Beijing for the BRI conference that culminated in a resolution to continue strengthening ties and promoting global growth and economy through policy coordination among participating economies, infrastructure connectivity, trade investment and industrial cooperation

To Africa in particular, China has become a significant economic partner. China has catapulted from being a relatively small investor in the continent to becoming Africa’s largest economic partner, providing infrastructure and investment loans that have helped the continent record massive expansion of roads, rail and other utilities. Obviously, the forum is crucial in strengthening existing relationships and opening new opportunities for cooperation.

To date, it is difficult to understand the full extent of China’s blueprint in Africa due to the data knowledge gap that exists. This vacuum has fueled urban legends and sensational stories, everything from charges of neocolonialism, persistent yet unfounded rumor that Chinese firms use convict labor en masse, to even a Chinese settler colony in Africa. However, to dispel or confirm these narratives Africa must take a critical review, audit and examination of its principal relationship with China and what it portends for Chinese influence and footprint in the continent.

Trade

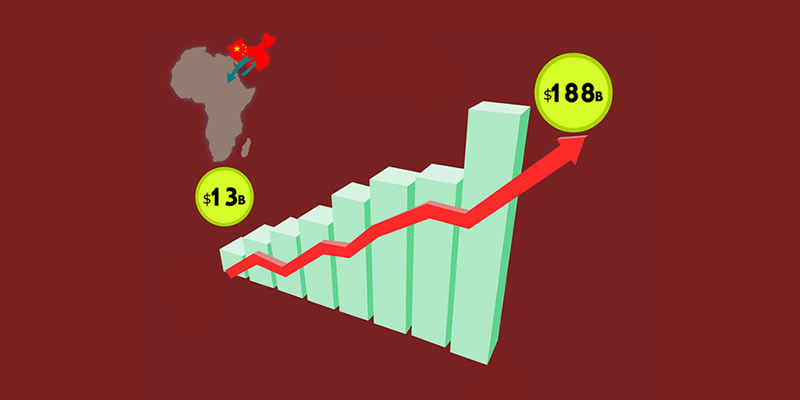

Since the turn of the 21st century, China has catapulted from being a relatively small investor in the continent to becoming Africa’s biggest economic partner. Africa-China trade increased from $13 billion in 2001 to $188 billion in 2015—an average annual growth rate of 21 percent. China has far surpassed Africa’s longstanding trade partners such as France, Germany, India, and the United States. According to a McKinsey and Company report dubbed Lions and Dragons in 2015, total goods trade between China and Africa amounted to $188 billion—more than triple that of India.

Statistics from the General Administration of Customs of China, in 2018, indicate that China’s total import and export volume with Africa was US$204.19 billion, a year-on-year increase of 19.7%, exceeding the overall growth rate of foreign trade in the same period by 7.1 percentage points. Among these, China’s exports to Africa were US$104.91 billion, up 10.8% and China’s imports from Africa were US$99.28 billion, up 30.8%; the surplus was US$5.63 billion, down 70.0% year on year. In December last year, China’s total imports and exports with Africa were US$18.27 billion, up 15.5% year on year and 2.1% month on month. Among these, China’s exports to Africa were US$9.55 billion, up 3.9% year on year and 3.0% month on month; China’s imports from Africa were US$8.72 billion, up 33.7% year on year and 2.2% month on month; the trade surplus was US$840 million, down 68.7% year on year and up 13.5% month on month. In 2018, the growth rate of China’s trade with Africa was the highest in the world.

China and Infrastructure

China has a long history of infrastructure investment in Africa, and this remains the country’s most visible legacy to this day. In the 1970s, China constructed the 1,710 km Tanzania-Zambia railway (Tan-Zam Railway completed in 1976), which linked landlocked, mineral-rich Zambia to the Indian Ocean. China’s aid for the project consisted of a nearly one billion interest-free loan, over one million tons of machinery and materials, and 50 thousand laborers to undertake construction efforts. Zambia’s first president, Kenneth Kaunda, hailed China’s support, and claimed the railway served as “a model for south-south cooperation.”

However, one of the megatrends of our times has been the growing presence of China in Africa’s infrastructure sector. Over the past two decades, China has helped to meet some of Africa’s infrastructure financing needs and is now the single largest financier of African infrastructure,financing one in five projects and constructing one in three mega projects.

Most funded projects are in the Transport, Shipping and Ports sectors (52.7 per cent), followed by Energy and Power (17.6 per cent), Real Estate (15 per cent, including industrial, commercial and residential real estate) and Energy and Power (13.1 per cent)

To date China has participated in over 200 African infrastructure projects. Chinese enterprises have completed and are building projects that are designed to upgrade about 30,000km of highways, 2,000km of railways, 85 million tonnes per year of port output capacity, more than nine million tonnes per day of clean water treatment capacity, about 20,000MW of power generation capacity, and more than 30,000km of transmission and transformation lines.

Foreign Direct Investment

China is poised to become Africa’s largest source of Foreign Direct investment. At the current growth rates, China will be Africa’s largest source of FDI stock within the next decade. China’s financial flows to Africa are around 15 percent larger than previous estimates. This discrepancy is found because official figures, which rely on banking-system data, do not cover informal money-transfer methods often used by smaller businesses. These methods include “mirror transfers,” in which a local payment is made into the Chinese account of an associate or family member, who in turn makes a local equivalent payment in Africa to the beneficiary’s bank account.

Aid

China is the second- or third-largest country donor to Africa Chinese official development assistance (ODA) and other official flows (OOF) to Africa together amounted to $6 billion in 2012. Chinese foreign aid expenditures increased steadily from 2003 to 2015, growing from USD 631 million in 2003 to nearly USD 3 billion in 2015. The United States promised somewhat more—$90 billion in the same period—but Chinese aid is more sought after. Unlike Western assistance, which comes mainly in the form of outright transfers of cash and material, Chinese assistance consists mostly of export credits and loans for infrastructure (often with little or no interest) that are fast, flexible, and largely without conditions. Thanks to such loans, the International Monetary Fund estimates that, as of 2012, China owned about 15 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s total external debt, up from only 2 percent in 2005. And McKinsey & Co. reckons that, as of 2015, Chinese loans accounted for about a third of new debt being taken on by African governments.

Debt

Most of China’s loans to Africa go into infrastructure projects such as roads, railways and ports. China’s loan issuance to Africa has tripled since 2012. New debt issuance by Chinese institutions to African governments increased dramatically in the past five years, rising to some $5 billion to $6 billion of new loan issuances each year in the 2013–15 period. The McKinsey report suggests that in 2015, these loans accounted for approximately one-third of new sub-Saharan African government debt. Most of these loans are linked to infrastructure projects, such as China EXIM Bank’s $3.6 billion loan to finance the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway in Kenya. From 2000 to 2017, the Chinese government, banks and contractors extended US $143 billion in loans to African governments and their state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

In 2015, the China-Africa Research Initiative (CARI) at John Hopkins University identified 17 African countries with risky debt exposure to China, potentially unable to repay their loans. It says three of these – Djibouti, Republic of Congo ( Congo-Brazzaville) and Zambia – remain at risk of debt distress derived from these Chinese loans. In 2017, Zambia’s debt amounted to $8.7bn (£6.6bn) – $6.4bn (£4.9bn) of which is owed to China. For Djibouti, 77% of its debt is from Chinese lenders. Figures for the Republic of Congo are unclear, but CARI estimates debts to China to be in the region of $7bn (£5.3bn). Angola is the top recipient of Chinese loans, with $42.8 billion disbursed over 17 years. Yet, Chinese loans are currently not a major contributor to the debt burden in Africa; much of that is still owed to traditional lenders like the World Bank.

Business

According to the McKinsey report , there are about 10,000 Chinese-owned firms operating in Africa today. Around 90 percent of these firms are privately owned. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) tend to be particularly in specific sectors such as energy and infrastructure, the sheer multitude of private Chinese firms working toward their own profit motives make Chinese investment in Africa a more market-driven phenomenon than is commonly understood. Chinese firms operate across many sectors of the African economy. Nearly a third are involved in manufacturing, a quarter in services, and around a fifth in trade and in construction and real estate. In manufacturing, an estimated 12 percent of Africa’s industrial production—valued at some $500 billion a year in total—is already handled by Chinese firms. In infrastructure, Chinese firms’ dominance is even more pronounced, and they claim nearly 50 percent of Africa’s internationally contracted construction market.

One-third of Chinese firms based in Africa reported profit margins of more than 20 percent in 2015. They are also agile and quick to adapt to new opportunities and they are primarily focused on serving the needs of Africa’s fast-growing markets rather than on exports.

Agriculture

According to CARI China has acquired 252,901 hectares of land in Africa. Cameroon alone accounts for 41% of all lands actually acquired: driven by two large purchases of existing rubber plantations (over 40,000 hectares each) in 2008 and 2010.China has also established 14 agricultural centres across Africa.

China has also taken an increasingly hands-on role in its work and investment related to African agriculture, leasing and developing land and in many instances being accused of “grabbing” large swathes of it. But as Deborah Brautigam’s reports the assumptions about China’s role in Africa are often not borne out in reality and the areas of land “grabbed” for investment are small compared to the vast areas identified by some.

Security

Over the past decade China’s role in peace and security has also grown rapidly through arms sales, military cooperation and peacekeeping deployments in Africa. Today, China is making a growing effort to take a systematic, pan-African approach to security on the continent.

China is now the second-largest contributor to the peacekeeping budget. Chinese personnel have served on missions in Africa for decades, but until 2013 they were small contingents in unarmed roles such as medical and engineering support. China now provides more personnel than any other permanent member of the Security Council – they numbered 2,506 as of September. Chinese peacekeepers now serve in infantry, policing and other roles in Africa.

In 2017, China established a 36 hectare Djibouti military facility.with a ten-year lease at $20 million annually. It has been described as a support base for naval anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, peacekeeping in South Sudan and humanitarian and other cooperation in the Horn of Africa, but has also been used to conduct live-fire military exercises.

Labour and Population

The number of Chinese immigrants in Africa has risen sevenfold in under two decades, The Annual Report on Overseas Chinese Study said the African continent was home to more than 1.1 million Chinese immigrants in 2012, compared with less than 160,000 in 1996, adding that 90 percent of the current total arrived after 1970. Initially, most labourers coming to Africa were from retail industry but today with the closer relationships with Africa, Chinese intellectuals and skilled professionals have settled in Africa.

The number of chinese workers by the end of 2017 was 202,689. In 2017, the top 5 countries with Chinese workers are Algeria, Angola, Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Zambia. These 5 countries accounted for 57% of all Chinese workers in Africa at the end of 2017; Algeria alone accounts for 30% of the numbers. These figures include Chinese workers sent to work on Chinese companies’ construction contracts in Africa (“workers on contracted projects”) and Chinese workers sent to work for non-Chinese companies in Africa (“workers doing labor services”); they are reported by Chinese contractors and do not include informal migrants such as traders and shopkeepers.

Media

There has been a significant increase of Chinese media on the African continent in recent years. This has taken place across various levels, including infrastructure development, training of journalists, production and distribution of media content, and investing directly in African media houses and platforms. The increased media footprint is widely seen as a way for China to extend its ‘soft power’ on the continent. But this is not the first time that China has established a media presence on the continent. As far back as the 1960s and 1970s, Chinese media was active in Africa.

However, since 2012, state-run media outlets have also pitched up in the continent, among them the Africa bureau of China Global Television Network (CGTN based in Nairobi) and China Daily Africa newspaper. China also takes African journalists to Beijing for training, while state-linked firms have made investments in local media outlets including buying a 20% stake in South Africa’s Independent News and Media firm (INMSA). The Beijing-based StarTimes Group has also become one of Africa’s most important media companies, increasingly influential in the booming pay-TV market. As it spread its foothold in Africa, the company has embarked on a project to provide solar-powered satellite television sets to 10,000 villages across Africa.

*****

China has not “taken over Africa”; she has merely joined with earlier groups of imperialists in grabbing a part of the African bounty. As a newcomer, her presence is more visible, but not yet as substantially deep-rooted as the long-standing European imprint.

She comes with two key differences: first, China does not yet have the military and diplomatic capacity to replace any of those Western powers in physically securing and enforcing the various trade routes and treaties needed to keep the global trade machine, upon which they all depend, running. Second, therefore, this venture cannot be implemented remotely, but by human displacement. Even a settler-overlord project may not work. What could work is one where millions of Chinese people are steadily shipped over to “yellow” Africa as a continuation of the anti-black ethnic cleansing and encroachment the Asians began centuries ago in South Asia.

The Africa of the ordinary people must therefore assert itself and force its concerns on to all public agendas. The struggle now is to hold a public conversation independent of these various imperialists and their allies.

Sources: McKinsey and Company report. Compiled by Mdogo.