Dark Friday

As he was leaving for work, Stephen Mumbo closed the door to his apartment. It was still dark outside, but he had to be at work early enough to finish a report and prepare for a meeting. In one hand he carried the lunchbox his wife, Roselyne, packed for him every night. In the other, he held his car keys.

A quiet, shy bespectacled man with a balding head and a nerdy aura, he was always polite to a fault. He was also a workaholic, rarely seen anywhere else but at his office desk. But this morning, as he left the apartment, got to the parking lot, and into his maroon Mitsubishi Lancer, registration plate KAS 843M, something else was on his mind.

He was tired, but that fatigue would have to wait. He had barely seen Roselyne and their infant daughter in the preceding two months as he had been busy undoing one of the biggest corporate messes in Kenyan history. It was his brief, but for most of the previous decade and a half, such assignments had been his life.

To anyone watching, nothing was outwardly unusual about Mumbo that cold Friday morning.

From his apartment building, the 9-storey Pangani Palace Apartments off Muthaiga roundabout, he joined the early morning rush hour traffic. Although Nairobi wakes up early to beat the city’s infamous traffic jams, it took him less than 30 minutes to reach his office in Westlands. The sun rose on the horizon and with it, the city. It would be the last time he would take that route.

As he took a gentle left turn off Waiyaki Way to the paved driveway of the twin Delta Towers, the headquarters of his employer, Stephen Mumbo was already a man on edge. But his permanent calm demeanor, which had only failed him on rare occasions, hid the turmoil beneath.

Mumbo waved at the guards as they let him through the barrier. He drove to his parking slot, reverse-parked into it, and walked to the lift. Once in, he pressed the 12 button and waited. When the doors opened, he got off and walked to his office.

Mumbo used his access card to enter the office a few seconds before 6:15 a.m. Even that early on a Friday morning, he was not the first person at the Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC) Kenya office. At least four of his colleagues were already at their desks, typing up reports, trying to meet deadlines and preparing for meetings.

Mumbo removed his suit jacket and draped it over his seat. On any other day, he would only wear it again if he had a meeting or if it got cold. He sat at his desk, which was a neatly arranged table with no personal items. It was where he spent days and nights working on assignments, and where, this fateful morning, he would sit one last time. On his mind was a report he had been toiling on for the previous two weeks that was due that morning. But there were many other things troubling him.

Mumbo used his access card to enter the office a few seconds before 6:15a.m. Even that early on a Friday morning, he was not the first person at the Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC) Kenya office. At least four of his colleagues were already at their desks, typing up reports, trying to meet deadlines and preparing for meetings.

Six weeks before that morning, UBA Bank had placed ARM Cement, a listed manufacturing company, under PwC’s management over massive debt. The company had been suspended from the Nairobi Stock Exchange (NSE) as its shareholders reeled in disclosures of hidden debts and other forms of corporate malfeasance. While for outsiders it was a story of yet another typical Kenyan company, for Stephen Mumbo it was a direct challenge.

As the Assistant Manager of Executory and Forensic Investigations, the complexities of understanding the company’s true position, and then figuring out ways to solve the mess, fell directly on his desk – and he was just the man for the job. He was not only reliable, he was also driven. In a profession that demands brilliance, he could be considered a proper nerd. Besides, he had worked for PwC for nearly a decade and a half and had proven his skills countless times. If there was a complexity you couldn’t untangle, on just about any project, Stephen Mumbo was the man to ask.

He’d spent 18-hour work days working on the ARM proposal, which was not unusual for him or anyone who worked at PwC. What was specifically different was that Mumbo was a perfectionist par excellence. Grammar was important to him; a comma out of place would unnerve him, and more than once he had chosen to file reports late rather than table them with errors. He approached his work, as one colleague put it, like the civil engineer he had been trained to be. One centimetre off, and the whole structure risks collapse. That perfectionism meant he spent hours and days labouring on not just getting the right proposals on paper, but also on making sure that the language in the reports was clear and concise. It made him irreplaceable, but at the same time, it meant that he could not be promoted.

Sometime between 7:30am and 7:40am, Mumbo asked a colleague whether there was any free meeting room on the 17th floor. There wasn’t, she told him. Despite having this information, he still went upstairs, hoping that the administrator there could find him one. He needed it for a meeting, which was scheduled for 9am, but he also had other things on his mind.

The only thing that might have caught anyone’s attention was that he wasn’t wearing his spectacles, which was rare. His eyes were red, but for a man in his profession, that was considered just another day at the office. It was also not unusual for him to go upstairs hours before a meeting. Since he had left his jacket draped on his chair, everyone assumed he was coming back.

On the 17th floor, Mumbo tried several rooms. He found someone talking on her phone in one of them. She asked him if he had booked the room. He said no, and closed the door. That woman was probably the last person to see him alive.

When he got to Kilimanjaro 2 meeting room, he found it empty. He closed the door behind him. He was physically alone, but no one will ever truly know what kind of torment he was going through. He walked across the room’s polished floors, passing the black and yellow chairs, probably tapping his fingers on the grey top mahogany table. Then he placed his Lenovo laptop on the table, walked to the window, and climbed outside. From there, he could see the Westlands rush hour traffic below him. He could see Waiyaki Way, and even the stretch he had turned into two hours earlier to get into his office, as well as the Westlands matatu stage on the other side of the road. There was the luxury car dealership at the end of the complex, and the parking lot between it and his building. But maybe he didn’t notice any of this as he steadied himself on the ledge.

Then he jumped.

To anyone watching from outside, the fall lasted the blink of an eye. One second Stephen Mumbo was standing on the ledge of the window, and the next he was on the balcony of the 2nd floor, fifteen floors down. It must have looked macabre, the sight of a man falling to his death against the backdrop of Delta Towers’ imposing façade. To the employees at SBM Bank, on whose second-floor window ledge Mumbo died, it sounded like a sudden thud.

Many things drove his choice of the 17th floor, including the fact that it was mostly empty at that time of day, and that from that high up, he was unlikely to survive the fall. Later images from witnesses in the buildings across show four first responders around his lifeless body dressed in a light blue shirt and black suit pants. There wasn’t much anyone could do at that point, and he was pronounced dead immediately after he was taken to the hospital.

Inside PwC Kenya, the immediate members of his team were told to go home or wait if they needed to see a counsellor. Someone retrieved Mumbo’s Lenovo laptop from the meeting room, and from it the report he had spent his last two months alive working on. Everyone else was ordered back to their assignments, even while Mumbo’s body still lay on a ledge below.

***

As the news of Stephen Mumbo’s fall broke in the capital city, people speculated on whether he had jumped or he had been pushed. On Twitter, people wondered whether there had been foul play; some connected the dots from Mumbo’s sensitive work as a forensic investigator to his fall. There are no cameras in the corridors outside the boardroom, only on the staircases. That blind spot would make it hard for investigators to determine if anyone had joined him in the room.

Others focused on the suicide angle; many wondered why a 41-year-old man with a well-paying job would choose to end his life. Some suggested domestic issues had driven Mumbo to his death; one strangely detailed tweet suggested infidelity. But the public speculation ignored the probability that only Stephen Mumbo knew what Stephen Mumbo was going through. In the absence of a suicide note in any form – none has been found – piecing back the last few years of his life is probably the only way to understand why he killed himself.

As the news of Stephen Mumbo’s fall broke in the capital city, people speculated on whether he had jumped or he had been pushed. On Twitter, people wondered whether there had been foul play; some connected the dots from Mumbo’s sensitive work as a forensic investigator to his fall.

By the time he died, Stephen Mumbo was one of only three employees who had been at PwC Kenya for more than 13 years. He’d only had one job outside PwC (as a design engineer between March 2003 and April 2004) before joining the accounting firm. The only other company he had worked for was a small Malawian smallholder farmer’s company where he had done a brief consultancy in 2016. PwC was, by all accounts, more home to him than his apartment was. The job fit his personality as it required a meticulous, borderline obsessive mind.

Mumbo was, by many accounts, a good boss and an effective team leader who avoided office politics. In a profession where kindness is rare, he was overly compassionate and helpful. Sometimes, according to several people who worked with him over the years, he would volunteer to help on a project and eventually take a leadership role. But he was the kind of colleague who took on team projects and then credited everyone else. According to at least one insider, the kind of work Stephen Mumbo was handling on ARM Cement was probably work that should have been handled by a team of six.

Mumbo’s perfectionism and thoroughness also made him irreplaceable. Most of the people who eventually became his bosses owed some of their success to him. He trained them, as he did many other people, but they passed him in rank because he was not assertive. In a meeting room, he would point out flaws in plans in a heartbeat, but recoil when asked how to change them. Instead, he would draft his thoughts and offer them to someone else to present.

But he enjoyed the work itself. The constant mental challenge must have been a thrill at the beginning of his career, but it slowly chipped away at his mental health.

By October 2018, he couldn’t take it anymore. “They [PwC] plied him with so much work, and he wasn’t the type to say no, so he did it anyway. He was always very well groomed, but always tired,” said a relative.

The firm

By the time Pricewaterhouse Coopers bought part of Delta Towers in late 2012 for Sh4.4 billion in a joint deal with the University of Nairobi, it was already one of the biggest auditing firms in the world. The company was founded in 1998 through a merger between Coopers & Lybrand and Price Waterhouse, and rebranded to PwC in September 2010. By then, it was present in 158 countries and 743 locations, battling it out with three other audit firms, Deloitte, EY, and KPMG. PwC had over 236,000 people in its ranks, among them a quiet Kenyan nerd called Stephen Mumbo.

The PwC Tower, one of the two towers that make up Delta Towers, became PwC’s new home from early 2013. It was a remarkable investment by a company partially owned by Indian billionaire Mukesh Ambani. PwC Kenya settled for Wing B of the 20-storey twin towers, occupying half and renting out the other half. Upper Hill, its former home, was losing its lustre as new buildings came up without the infrastructure to support them. Now, in the newest building on the corner of Waiyaki Way and Ring Road Westlands, its employees were spoilt for choice on where to live. Location was important because many of them would work long hours, driving to and from work while the city slept.

As an employer, PwC Kenya consistently ranks as one of the best places to work in Nairobi. Entry-level graduate trainees earn an average monthly salary of Sh120,000, and its partners, according to Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA), are some high-net-worth individuals with gross annual incomes of between Sh350 million and Sh1 billion.

For the ARM job, PwC charged Sh65.6 million for the first three months, in addition to Sh7.9 million for preparatory work. While the PwC partners appointed to do the job were Muniu Thoithi and George Weru, the actual legwork went to a quiet nerd on the 12th floor called Stephen Mumbo. Thoithi and Weru would earn Sh43,000 per hour, while associate directors would earn Sh37,800, senior managers Sh30,000, and project managers Sh25,000 per hour. As a manager, Mumbo’s pay most likely fell in the two lower ranks. But to earn his keep, he would have to spend hours on end poring through reports, preparing his own recommendations, and presenting them to his bosses and the client.

By the time Mumbo got to his desk at 6:15am on Friday, 12th October, he had had less than three hours of sleep. He had gone home at 1am the previous night. He fell asleep fast, but he was clearly distressed, according to several close family members. He kept tossing and turning and woke up before daylight to get back on the grind.

Multiple conversations with past and current employees of PwC Kenya paint the picture of a firm with little space for work-life balance. Long hours and mind-breaking work are the norm, and most employees, like Stephen Mumbo, tend to live close to Delta Towers to ease the commute to work. The employee turnover rate is understandably high, as the work environment becomes more unbearable as one ages and begins seeking a better work-life balance.

Describing his experience at PwC, one employee said, “Deadlines have to be met and bonuses have to be earned. Your health is your problem. If you can’t handle the pressure, quit.” Another termed PwC’s work culture as “ruthless”, adding that even “having a baby is frowned upon.” Lunch breaks, several employees said, are not exactly an option: “Nobody goes for a long leisurely lunch at PwC. Many people eat at their desks.” The average work day, said several employees, is 14 hours. If you are on a project, it’s not unusual to work 18-hour days.

Under Kenyan law, normal working hours are between 45 hours and 52 hours a week for day employees and 60 hours for night employees. The law also provides for at least one rest day a week. At 14-18 hours a day, Stephen Mumbo and his colleagues were clocking between 84 hours to 126 hours a week, twice the legal limit. While the law also provides for overtime, the overriding element is that it be properly compensated, and not result in overworking, which impairs sleep patterns and increases the risk of stress, depression, and lower immunity. Overwork has been associated with heart problems, and among low-income workers, with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes. People who overwork tend to lead unhealthy lifestyles, having less time to exercise, eat. They also tend to smoke or drink more.

Describing his experience at PwC, one employee said, “Deadlines have to be met and bonuses have to be earned. Your health is your problem. If you can’t handle the pressure, quit.” Another termed PwC’s work culture as “ruthless”, adding that even “having a baby is frowned upon.”

Stephen Mumbo seemed to have navigated many of the physical challenges of overworking for almost a decade and a half. He was in good health, didn’t smoke, and barely drank alcohol. But the mental strain was showing.

All the interviewees for this story did not want to be named for fear of retribution for breaking company policy. In more than one case, there were also descriptions of the kind of retribution they might face, down to being put on track to be fired. More often than not, the interviewees still within PwC Tower outlined their basic exit plans and described Mumbo’s death as the latest in a series of wake-up calls.

For those who choose to stay, like Stephen Mumbo, the back-breaking work eventually leads to burnout. There was at least one other breakdown at the office in 2017, and several employees whispered about people self-harming or using drugs to cope with the pressure. For Stephen Mumbo, years of such pressure had finally taken their toll.

***

Mumbo’s distress on that last night was not the only time he had shown signs of work-related stress and depression. In the years before his death, he had had at least three visible episodes of burnout and mental distress at work. In 2015, he had a breakdown in the office and walked out on his boss. He was away from the office for a month. Meanwhile, work was still piling up; Shah Karuturi, the Kenyan subsidiary of the world’s biggest producer of cut roses, was placed under administration sometime during his break. This project was on his desk when he got back.

Then, in mid-2017, a colleague recalls, Mumbo fell asleep in the middle of a presentation with a client. “He was totally burned out, but his bosses simply told him to go to another boardroom and sleep for 45 minutes and then get back to work,” remembered the colleague. Such was life for him, going from one burnout to the next.

The third instance was perhaps the most significant in piecing together Stephen Mumbo’s last years alive. It happened years before he finally took his life, and linked back to the pillars in his adult life.

Run to the finish

Mumbo’s village in Kisumu, Nyamasaria, is a hot, dry, humid area. The land is infertile because its black cotton soil sucks the life out of any cash crop. Only weeds, euphorbia, and coarse grass are stubborn enough to grow on the land.

It was in this unforgiving terrain that Stephen Henry Mumbo was born to Arthur Waore Mumbo, an administrator at KEMRI, and Abigael Waore, a teacher at Nyamasaria Primary School in 1977. Mumbo was the last-born in a family of five.

Arthur Waore died in 1992, the year before Stephen joined St. Paul’s Amukura. The young teen moved to Alupe, Busia, to live under the care of his uncle, Mzee Obura, a doctor who still works for KEMRI. All accounts of Stephen Mumbo then match the man he would become: quiet, studious, and driven. According to his cousin, Fred Obura, Mumbo was more than just a brother. They were best friends and even went to the same high school.

Then, in mid-2017, a colleague recalls, Mumbo fell asleep in the middle of a presentation with a client. “He was totally burned out, but his bosses simply told him to go to another board room and sleep for 45 minutes and then get back to work,” remembered the colleague. Such was life for him, going from one burnout to the next.

In the 1990s, St. Paul’s Amukura, founded by Catholic priest Father Louis Okidoi in 1962, was an academic giant in what is now Busia County. The school motto, Cursum Consumavi, is Latin for “Run to the Finish.” When Stephen Mumbo was a student there, between 1993 and 1996, he lived in Nehru dormitory, named after the charismatic Indian leader.

In his teens, Stephen Mumbo walked awkwardly and avoided conversation. Several fellow alumni of St. Paul’s describe Mumbo’s shyness with fascination. Mumbo was, one says, the guy who wanted the key to the library when everyone else was chasing girls and dates. Odeo Sirari, a KTN news editor, was in Form One when Mumbo was in his final year. “As a new student, it was easy for me to notice Mumbo because he looked so serious, a total book worm,” recalls Sirari.

Another schoolmate, Caleb Etyang, who was a year ahead of Mumbo, says Mumbo would never be found on the school Isuzu bus, christened Kisisiata 3, which served the school between 1990 and 1999, and was driven by a gentle old man the boys fondly called Boyo. “He wasn’t a guy to go for sports or drama outings, he was much more at home in the school and in the library.” In his first two years at the school, he was the class prefect. In his last two years, he was the library prefect.

Mumbo topped the class of 1996 at the school, his only disappointment being that he hadn’t beaten the record of Adiema Aura, a renowned educationist who attended the school in the 80s. He’d only failed to overthrow Aura because he didn’t do well in Kiswahili; he scored an A-minus in the subject.

From St. Paul’s, he made his way to JKUAT, where he would spend the next few years training to become a civil engineer. Engineering offered the challenges a nerd like him yearned for, with its tenets of approaching problems and challenges with a tenacity that combined knowledge, skills and experience. After graduating, he did an accounting course and then took a brief engineering gig. Then he joined PwC Kenya, where he would spend the rest of his life, save for two unpaid sabbaticals.

Throughout this life, Mumbo relied mostly on his mother, Abigael, for emotional support. He had his siblings as well, as well as his adopted ones who were in fact, his cousins. But it was Abigael who represented the most profound influence on her shy young son’s life before and after school.

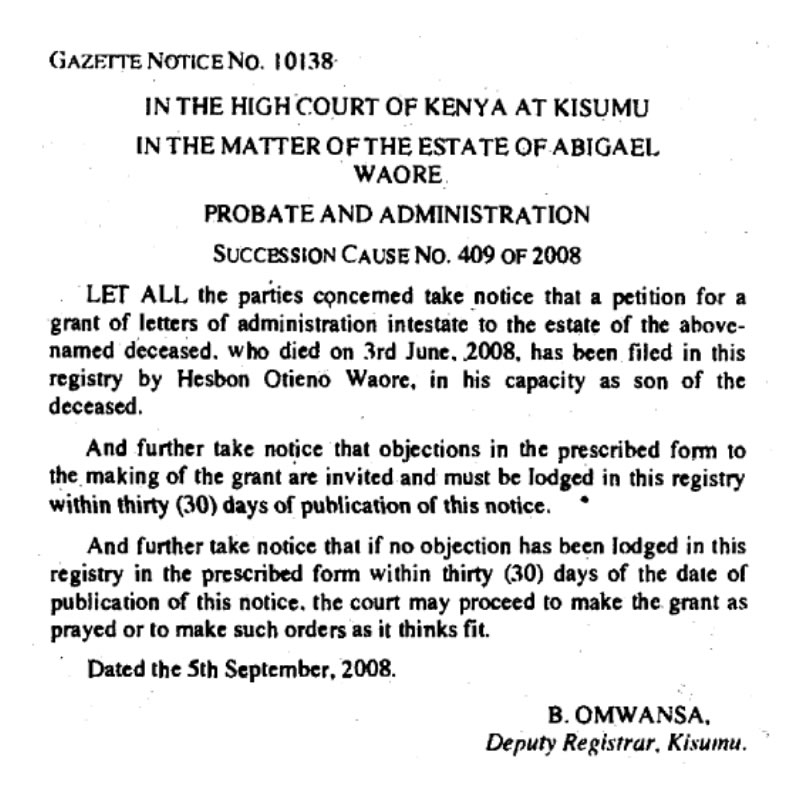

Then, on 3rd June 2008, Abigael Waore died.

Multiple accounts point to a marked change in Mumbo’s life, work, and demeanor after his mum died. He simply couldn’t work anymore; he took a one-year unpaid sabbatical before going back to work. At some point, either then or after, Mumbo also mounted a massive portrait of his mother in his bedroom. Her face was the last thing he saw before he slept and the first thing he saw when he woke up.

Colleagues say that whenever he was not shy, he would talk about his mum a lot. After she died, he mostly talked about his wife Roselyne. They had been married for seven years but had spent a considerable time apart as Roselyne focused on a project in Kisumu and Mumbo toiled at PwC Tower. On days when they were together, his lunch box was the source of envy, as colleagues listened to him go on and on about his wife’s cooking. On any day, even when out of the country on assignment, he would speak to her on the phone for at least an hour.

In the three months before his tragic fall, he also talked about his daughter. The couple had tried to have a baby for several years before finally settling on adoption to grow their family. The toddler was a new addition, and a happy one at that. Mumbo often talked about his daughter, but also said how he didn’t get enough time to be with her.

The patterns

Mumbo’s suicide was not the first time a PwC employee had died after jumping from a floor in a PwC office. In April 2016, a 23-year-old employee of the PwC headquarters in London had jumped to his death from PwC’s ten-storey office building. His decision was attributed to a secret gambling habit, which he had begged his parents not to inform PwC about. He died on a walkway outside the office.

In another case, in May 2012, a 46-year old man jumped off the eighth floor of the PwC building in Largo, the third largest city in Pinellas County, Florida. In 2015, a director at PwC in the UAE, Jumana, was found dead in an apparent suicide pact with her sister, Soraya Saiti, at the base of a building under construction in Amman, Jordan. Then in August 2017, a PwC director named Werner Haupfleisch died by suicide in his home in Royldene, South Africa.

While none of these deaths were directly linked to PwC’s organisational culture, there have been other related deaths. In 2011, for example, Angela Pan, an auditor at the Shanghai PwC office, died ten days after first showing flu-like symptoms. Although her death was attributed to viral encephalitis, social media users of Sina Weibo speculated that she had been “worked to death”, Sometime before her death, Pan sent an update on Sina Weibo that said, “I can accept overtime. I can also accept out-of-town business trips. But on learning a young worker died from fatigue at KP (KPMG), I feel something has broken my bottom line to endure.” She had only worked for the company for six months, after graduating from Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Faith Atsango, a psychologist, says that work-related stress should be classified as a safety hazard. “People in high pressure jobs are prone to have mental breakdowns,” she adds, “and such incidents should be treated as physical health and safety issues at work.” Atsango says that similar to how factories provide safety gear, stressful work environments should find ways to help employees cope, and ease burnout. Many of these are included in the Occupational Safety and Health Act, which also safeguards employees from “mental strain”.

Faith Atsango, a psychologist, says that work-related stress should be classified as a safety hazard. “People in high pressure jobs are prone to have mental breakdowns,” she adds, “and such incidents should be treated as physical health and safety issues at work.”

Despite these safeguards, high unemployment and weak enforcement of labour laws mean that work-related stress is not properly addressed. Mental health is still largely a taboo topic, despite an increasing number of deaths directly connected to it.

Part of the stigma attached to mental health is gender-related; statistics show that more than 70 per cent of the suicide-related deaths in 2017 were of males. Two days after Mumbo’s death, another man jumped into a borehole in Matisi Estate, Kitale. Five months before that, another man had jumped off the 8th floor of the 15-storey NSSF building in Mombasa.

There are numerous reasons for the gender disparity, most of them revolving around the social silence on depression and other mental health issues among men. Even worse, the stresses of living and working in a fast-paced urban centre pile up. The stresses include underemployment, overwork, length of the commute to work, and stagnant pay levels in a struggling economy.

A 1982 study on the subject showed that while the population in Nairobi grew by 7.5 per cent between 1975 and 1979, the rate of suicides grew by 300 per cent. The study also found a pattern in the months with the highest suicide rates; suicides tend to occur in the months of January to March, April to June, and October to December. There have been other studies focusing on at-risk groups, such as university students, but there is barely any substantive research on work-related stress and depression.

Then there’s the law. Instead of the law taking a pragmatic approach to the reasons why people take their own lives, it treats suicide as a crime. Attempted suicide is a misdemeanour punishable by two years’ imprisonment or fines, or both. This means that if Stephen Mumbo had survived his fall, which was unlikely, he would have promptly been arrested and thrown before a judge. That legal perspective and the social stigma also mean that suicide goes largely unacknowledged as the social issue it is.

Despite the legal and social hurdles, there have been some attempts to provide psychological wellness for several at-risk groups. In October, the same month Stephen Mumbo died, the National Police Service created a new department to assess the psychological wellness of officers. There had been at least five reported suicides of police officers in the preceding months. A few months later, the education ministry raised the alarm on an increasing number of death by suicide among university students.

In corporate workplaces such as PwC Kenya, the inclusion of psychological wellness has been at best abstract. PwC Global has made several public commitments to facilitate mental health awareness within its ranks. PwC UK, for example, has a “Green Light to Talk Day” and hired Beth Taylor as its new mental health leader in January 2016. PwC Malaysia has a “FitPwC” programme that combines physical and mental wellbeing. PwC Kenya does not have any such programme, and several employees described recent events, such as a meeting where management sought ideas on how to improve the work environment, as window-dressing.

As a consulting firm, PwC has published several reports on workplace stress. In 2017, PwC UK published a report on tackling workplace stress with technology. Three years before that, PwC Australia published a report titled “Creating a mentally healthy workplace.” The irony of such reports, according to a former long-term employee of PwC, is that they were most likely prepared by people who were themselves working in a mentally unhealthy environment.

The aftermath

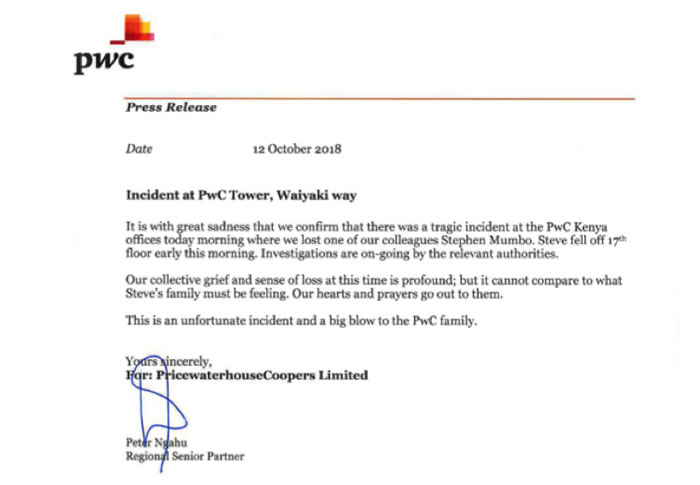

A few hours after Mumbo’s death, Peter Ngahu, PwC’s regional and country senior partner, held a press conference where he said, “It’s difficult to keep track of what each and every person is doing.” He refused to answer the question about whether Mumbo had been alone in the meeting room before he fell to his death. His response was: “He may have had a meeting, but he’s not here to answer the question.”

After that, Ngahu and Mumbo’s bosses, Muniu Thoithi and George Weru, declined any more media interviews into the death. Both Ngahu and Thoithi didn’t pick calls or answer text messages about the company’s work culture and measures they would institute to help employees deal with work-related stress. Reached for comment, George Weru declined, saying “No, no, no, I would not wish to say anything about this issue. The boss, Ngahu, issued a press statement and held a press conference on the matter last Friday.”

At PwC Tower, life continued almost as if nothing significant had happened there on October 12th. If Mumbo’s death had been “a big blow” to PwC Kenya, as Ngahu termed it in his press release, then it didn’t show. There was counselling for a few of the staff members in Mumbo’s team, but then everyone went back to work even before his body was removed from the scene.

The ARM project, his last, continued unabated, as did the entire firm. Eleven days after he stepped off the ledge of the 17th floor meeting room, ARM’s creditors approved an extension of PwC’s mandate to September 2019. It will be going on to this next phase without one of its ablest minds. In a meeting on October 22nd, the creditors also gave PwC permission to implement several options to revive the company. These, most likely sourced from Mumbo’s work, include getting a strategic investor and selling off some of the company’s key assets. It is unclear whether he had been the one who discovered that for years, ARM Cement had been treating a loan to its Tanzanian subsidiary as a performing loan while Maweni had been defaulting for years.

At PwC Tower, life continued almost as if nothing significant had happened there on October 12th. If Mumbo’s death had been “a big blow” to PwC Kenya, as Ngahu termed it in his press release, then it didn’t show. There was counselling for a few of the staff members in Mumbo’s team, but then everyone went back to work even before his body was removed from the scene.

***

Even before the shock of his sudden death waned, Mumbo’s friends and family organised meetings and fundraisers. At Tumaini Meeting Chambers behind Kencom House, they planned a farewell to a man who had seemed like he had it all. Many of his colleagues could not make it to the meetings because they were working. Instead, they sent cash donations and condolences.

On Friday, 26th October 2018, exactly two weeks after Mumbo had ended his life, they left in a convoy from Montezuma Funeral Home and drove to Mumbo’s home in Nyamasaria. The next day, at 9 am, they sat as the priest prayed, and then watched in grief as the casket bearing Mumbo’s body was slowly lowered into the grave. It was heartbreaking, a tragedy by any measure. A man who, after living off his brilliance, had ended up back in the unforgiving soil where he had first seen the world. For Roselyne and their daughter, it was the beginning of a life without Mumbo, who was at the time the sole breadwinner in the household.

On the 2nd floor ledge at Delta Towers, where Mumbo breathed his last, the dent his body left is still prominent, a stark reminder of his tragic end. In the parking lot, his Mitsubishi Lancer sat untouched for months, parked in the same spot where he left it.