I was cooped up in my Houston apartment in the United States on 15 November 2017 when Twitter chittered with the news that a coup was currently being carried out in my homeland, Zimbabwe. It was a searing night, deathly silent here in Houston, where it was still the evening of November 14. In Zimbabwe, an apricot-tinged sky was greeting Zimbabwe Military Major General SB Moyo’s early-morning announcement on national television that the army had taken over the country in order to return it to “normalcy”.

But even his assurances of order felt precarious. It was as though something terrible, as is the nature of coups, could still happen, such as a horrific breakout of civil war that would persist for years, catapulting us into a nightmare from which we would not be able to wake up. I remember doubling over, as though someone had punched me.

And then, surreal images of ordinary people like myself taking to the streets alongside menacing army tanks to march against Robert Mugabe flooded social media. I remember refreshing and re-refreshing my feed, squinting at the screen, trying not to disbelieve my eyes. Was this the same army? This army I had grown up fearing, which I’d seen destroying people’s homes and beating street vendors during Operation Murambatsvina (Operation Clean Out the Rubbish) in 2005? The army being broadcast all over the world wasn’t brutalising the marching populace. No…it was…protecting —protecting? —people just like me as they marched against Robert Mugabe.

The importance of this moment cannot be overemphasised. Even as we were jumping from the frying pan into the fire, it was hard not to participate in the joy of being able to march freely against Robert Mugabe. It was sublime. In our Zimbabwean universe, ruthlessly built up and curated for us by Zanu PF, this — marching against Mugabe with the army’s assistance and protection — wasn’t something that could happen. And yet, it was happening! It was just too delicious not to enjoy! It opened up the spirit and the imagination to endless possibilities for Zimbabwe’s future. Seeing people like me daring to hug the soldiers, laughing with them and posing for selfies alongside those sinister army tanks felt, even if momentarily, like a sweet taste of freedom, the kind of Zimbabwe we could one day have…

The importance of this moment cannot be overemphasised. Even as we were jumping from the frying pan into the fire, it was hard not to participate in the joy of being able to march freely against Robert Mugabe.

I remember looking around my apartment in Houston, dazed, and asking myself, “What am I doing here?” I should have been home. I should have been part of the crowds running on those Bulawayo streets, holding the Zimbabwe flag high above their heads, letting it spread and flutter in the wind in all its resplendent colours, billowing like a Super(wo)man cape. I cried all alone in my apartment, with no family to celebrate with me. I called to check on loved ones at home, only to be filled with envy at their gurgling, joyous laughter pealing in my ear across the many miles that separated us. I winced at not being home with them during this time. Briefly, I toyed with the prospect of dropping everything and catching a flight home.

But I quickly abandoned this idea. There was still a sense of precarity in the air, as though anything could still yet happen during this moment that felt like a refraction of many different realities and expectations simplified and repackaged into one – that of the army and the people as One.

Watching people marching alongside the army, I felt an unshakeable sense of dis-ease. In the background of this euphoria, behind the powerful visuals telling a story of a “new dawn” for Zimbabwe, were unsettling optics. As the festivities were going on, there was the ruthless purging of “criminals” around Mugabe—this done, ironically, by those from this same dispensation and who, in other differently-staged circumstances could well be considered “criminals” themselves. In darker events, away from the glamorous camera optics, abductions and beatings were being carried out by these same crop of soldiers seen genuflecting with ordinary people on the streets of Zimbabwe.

I released my pent-up energy on social media, joining others in energetic Twitter debates filled with a dreadful sense of foreboding. “Did we know what we marched for today?” I asked. I was mostly on Ndebele Twitter, where, inevitably, debates and questions about the Gukurahundi Genocide—Zimbabwe’s original sin—sprang up, with an army of faceless trolls doing their fair share of work to sow confusion and misinformation in what was rapidly become a “virtual Gukurahundi storm”.

Many people were angry that this landmark march and its optics were being questioned. Understandably, it felt as though their joy was being questioned, and possibly shamed. Vicious arguments broke out on Twitter, with problematic divisions that became amplified to the extreme in polarising debates on social media —between, for instance, those Zimbabweans who were actually at home on the ground marching, and those like myself who were “tweeting the revolution” from the comfort of their diasporic enclaves.

Perhaps this was the wrong moment to ask questions about the march. The people were dreaming. The joy on those faces, our faces! Caught by the flash of a camera, animated and gorgeous shiny cheeks plump with mirth. Where had you ever heard such collective laughter? Where would you ever hear it again?

Many people were angry that this landmark march and its optics were being questioned. Understandably, it felt as though their joy was being questioned, and possibly shamed. Vicious arguments broke out on Twitter, with problematic divisions that became amplified to the extreme in polarising debates on social media…

**

Franz Fanon talks about moments such as these in The Wretched of the Earth, where it seems as though the people and the country’s post-independence leaders are One. The country’s post-independence leaders promise the people that change is coming, working up the people into a frenzy of excitement. At the same time, these leaders leverage this excitement with the international community, saying, “Look, the people are excited, they are nervous, only we can calm them, work with us.” This opens up, in our contemporary moment, the way for neoliberal politics to take root—“Zimbabwe is Open for Business” has been the new President Mnangwagwa’s mantra.

Sometimes, the people take this call to change seriously and to begin to act to realise it, to enact their urgent desire for change. The celebrations on the streets in November 2017, with army and citizens hand in hand, was one such instance of this euphoria. The optics were powerful. I felt them. I was taken by them. And yet, the fissures of this moment began to show early on. In December 2017, soldiers, the heroes and heroines of only a few weeks before, were seen patrolling the streets of Zimbabwe assaulting citizens.

These fissures became even more apparent leading up to, during and after the contested July 2018 elections. The people were ready to enact their various ideas of change that they had marched for in November 2017. Some of these collective demands included electoral reforms and transparent elections. There was electricity in the air during this time, a heady dreaming. I was in London during the 2018 elections, where I found a great community of youthful, engaged Zimbabweans like myself. We met regularly and discussed what was going on at home, sharing our fears, hopes and dreams. It was an exhilarating time. Twitter, once again, fostered a much-needed sense of community with the people at home.

If there had been confusion before as to the optics of the November 2017 march, things were certainly clearer now. On 1 August 2018, protesters went out onto the streets of Harare to march against an increasingly suspect and vague electoral process. In an unprecedented move, armed soldiers from the Zimbabwe military were unleashed onto the streets to fire live ammunition against the unarmed protesters. Army and citizen, who had, just seven months before, held hands in song and dance, were now, once again, embroiled in the violent relations of state abuse.

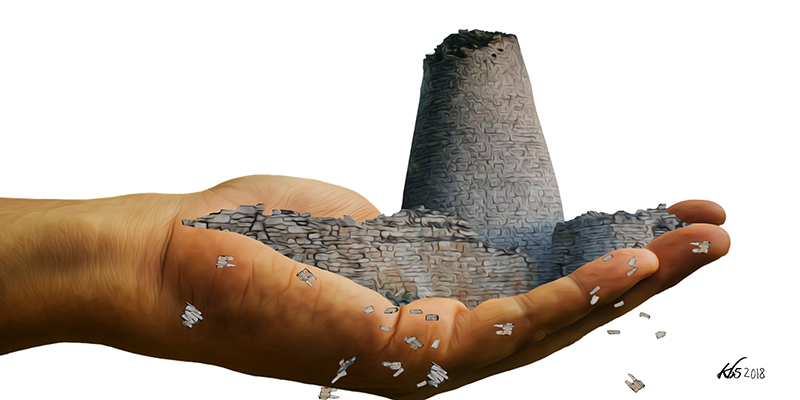

In the mind-frying euphoria of that landmark moment in our country in November 2017, we had mistaken things, laughing with the soldiers, kissing their cheeks, crowning them our heroes. They were not there to serve us, the citizenry. No, it was us, the citizenry, who were there, just like those youthful, handsome soldiers of ours, to serve the army commanders, some of whom, like Vice President Chiwenga, aka General Bae, now parade the halls of government. It was us who had provided assistance—and not us who had been assisted—in the November 2017 “coup-lite” to legitimise the intra-party politricks of Zanu PF. Once again, we were just a footnote in our own history.

George Orwell writes about authoritarianism’s perversion of history in his essay “The Prevention of Literature”. At stake, he writes, is not just a matter of freedom. “The controversy over freedom of speech and of the press is at bottom a controversy of the desirability, or otherwise, of telling lies…From the totalitarian point of view, history is something to be created rather than learned…Totalitarianism demands, in fact, the continuous alteration of the past.”

The blatant rewriting of history about events as fresh as the August 2018 shootings is a case in point. Even in the face of video footage, Zimbabwe’s army commanders went on to say that no soldiers killed protesters on the streets of Harare on August 1. If a government-sanctioned commission cannot agree on the basic facts of something as recent as these August 2018 shootings, should anyone have faith in the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission set up to shed light on the devastating Gukurahundi Genocide that took place more than 30 years ago?

The blatant rewriting of history about events as fresh as the August 2018 shootings is a case in point. Even in the face of video footage, Zimbabwe’s army commanders went on to say that no soldiers killed protesters on the streets of Harare on August 1.

“Truth is optics,” says Dumo, the self-styled leader of the Mthwakazi Secessionist Movement in my novel House of Stone. “We’re trying to own the truth…”

Zamani, the novel’s narrator, upon hearing this, is sceptical: “Dumo could often sound perilously like the very people he was denouncing.”

Welcome to the new Zimbabwe.