Despite the talk on the necessity and content of constitutional amendments, there has been little or no discussion on the process to effect legal changes to Kenya’s Constitution. It is a Catch-22 situation. On the one hand, Parliament cannot amend the Constitution without violating it. On the other hand, there is no way the Constitution can be amended without Parliament.

There are only two ways to amend the Constitution of Kenya 2010, both of which are detailed in Chapter Sixteen. The first, by parliamentary initiative, is provided in Article 256. This entails a constitutional amendment in the form of a bill that can be introduced in either house of Parliament. The bill must be subject to public participation and must pass by at least two-thirds majority of Parliament, which means at least 234 votes in the National Assembly and 45 in the Senate at both the second and third readings of the bill.

The second method to amend the Constitution is through popular initiative provided in Article 257, which vests the power to initiate a constitutional amendment in the people. A popular initiative may be initiated by a citizen, a movement or a political party through collecting the signatures of at least one million registered voters. Once the popular initiative is submitted to the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), it must be in the form of a draft bill.

Thereafter, the IEBC, after confirming that the popular initiative complies with the requirements of Article 257, must within 3 months of its receipt submit the draft bill to all 47 County Assemblies for consideration. At least 24 County Assemblies must approve the popular amendment bill (within 3 months), and thereafter the bill shall be submitted to Parliament where it must pass by a simple majority in each house before being submitted to the President for assent and signature. Given the recent resignations of some IEBC commissioners, this option presents the further complication of the IEBC lacking the quorum needed to act. Furthermore, the replacement of IEBC commissioners also requires the approval of the National Assembly, according to Article 250(2)(b).

The Constitution of Kenya, while less than a decade old, is the result of decades of struggle by ordinary Kenyans to assert the right to control their destiny and to wrest control from politicians and political dynasties.

Parliament is the common denominator in both constitutional amendment processes. This makes sense as it is a reflection of the important role that Parliament plays as the institutional manifestation of the “sovereign power” of the people from which the Constitution derives its authority.

In addition, with both methods, the parliamentary initiative (Article 256) and the popular initiative (Article 257), the provisions of the amendment must be subject to a referendum if they relate to 10 areas, including: the supremacy of the Constitution (255(1) (a); the sovereignty of the people 255(1)(c); the national values and principles of governance 255(1)(d); the Bill of Rights 255(1)(e); the independence of the Judiciary and the independent offices to which Chapter Fifteen applies 255(1)(g); the principle and structure of devolution 255(1)(i); and the provisions of Chapter Sixteen 255(1)(j). However, a referendum can only be conducted after the proposed constitutional amendment passes in Parliament.

Again, this is a constitutional affirmation of the source of power, which “belongs to the people of Kenya”. The Constitution of Kenya, while less than a decade old, is the result of decades of struggle by ordinary Kenyans to assert the right to control their destiny and to wrest control from politicians and political dynasties. So, the only way the people of Kenya have accepted that the Constitution can be amended is through Parliament. Parliament is a creation of the Constitution which defines its composition and role.

One of the most significant changes in national governance after 2010 was the creation of a bicameral legislature, with Article 93 establishing Parliament which consists of two houses – the National Assembly and the Senate. Articles 97 and 98 define the National Assembly and Senate as elective bodies. As elective bodies, the principles of the electoral system provided in Article 81, as well as the composition requirements of elective bodies in Article 27(8) of the Bill of Rights also apply to Parliament.

Therefore, in evaluating whether Parliament has the capacity to enact any amendments to the Constitution, as provided in Chapter Sixteen, we must first determine two things: one, that Parliament is constitutionally compliant, and two, that it is acting in exercise of authority granted to it by the Constitution. Without meeting the first requirement, we cannot proceed to the second. A constitutionally compliant Parliament cannot legally act outside its authority as prescribed in the Constitution. And an unconstitutional Parliament, one composed in violation of the Constitution, cannot legally perform any acts as it fails the test of legality established by the Constitution.

The current Parliament, the second after the promulgation of the Constitution of Kenya in 2010, has a membership of 416 persons (excluding both Speakers). Based on data from the IEBC after the August 8th 2017 election, the second post-Constitution parliament is 77% male and 23% female. Parliament complies fully with the numerical provisions provided for its membership: there are 349 members of the National Assembly (excluding the Speaker), as required in Article 97, and 67 members of the Senate (excluding the Speaker), as required by Article 98. However, neither Parliament as a body nor either house individually complies with Articles 81(b) and 27(8).

Parliament’s failure to comply with the gender composition requirement of its membership renders it unconstitutional, just as its failure to comply with its numerical composition (fewer or more than 416 MPs) would render it unconstitutional.

Article 81 in Chapter Seven on Representation of the People lays out general principles for the electoral system, which include universal suffrage, free and fair elections and that “not more than two-thirds of the members of elective public bodies shall be of the same gender” 81(b). Article 27(8) provides that “not more than two-thirds of the members of elective and appointive bodies shall be of the same gender”. These are mandatory provisions of the Constitution and fix the constitutionality of Parliament as a body. They thus determine whether Parliament is legally capacitated to act at all.

Parliament’s failure to comply with the gender composition requirement of its membership renders it unconstitutional, just as its failure to comply with its numerical composition (fewer or more than 416 MPs) would render it unconstitutional. The actions of an unconstitutional Parliament lack legal authority. An illegal Parliament cannot perform its constitutional functions; it cannot, for instance, enact laws, it cannot approve appointments to Cabinet or to the IEBC, nor can it amend the Constitution. An illegal Parliament is outlawed in Article 3, which states: “Any attempt to establish a government otherwise than in compliance with this Constitution is unlawful.”

It is, therefore, an irrefutable fact that the second post-Constitution Parliament is unconstitutional and illegal. Indeed, this is also the official position of the Office of the Attorney General, the government’s principal legal adviser. In 2012, concerns about a potentially unconstitutional Parliament and the constitutional crisis this would precipitate, led the then Attorney General, Prof. Githu Muigai, to seek definitive interpretation of the provisions of Article 81(b) and 27(8) as they relate to Parliament. The Supreme Court of Kenya settled the question in its majority opinion, holding that while the first post-promulgation Parliament would be exempt from compliance with Articles 27(8) and 81(b) in its composition, that same Parliament would be required to enact legislation to implement the gender principle in Article 81(b) by August 27, 2015.

The Supreme Court of Kenya settled the question in its majority opinion, holding that while the first post-promulgation Parliament would be exempt from compliance with Articles 27(8) and 81(b) in its composition, that same Parliament would be required to enact legislation to implement the gender principle in Article 81(b) by August 27, 2015.

The effect of the Supreme Court’s 2012 judgment was two-fold: first, it provided temporary legal cover to an otherwise unconstitutional Parliament, and second, it established that without judicial interpretation and decree, a Parliament that fails to comply with Articles 81(b) and 27(8) is indeed illegal. By its decision, the Supreme Court affirmed the position of the Office of the Attorney General that a Parliament that failed to comply with provisions of the Constitution in its composition would create a constitutional crisis.

The Supreme Court’s temporary reprieve required the 11th Parliament to enact a law before the next general elections scheduled for August 2017, thereby ensuring there would be no constitutional crisis as the 12th Parliament, and all subsequent parliaments, would be composed in compliance with the Constitution. However, despite the Supreme Court and subsequent High Court judgements ordering Parliament to enact legislation to ensure compliance with Articles 27(8) and 81(b), Parliament has refused to abide by the provisions of the Constitution and the law.

The foundation on which the 2012 Supreme Court judgement rests is a determination that as an illegally composed body, Parliament, without the exemption granted by the Supreme Court, would be unconstitutional and legally incapable of enacting any of its constitutional functions. The current Parliament has no such protection and therefore exists entirely outside of the constitutional order.

How then can a body that has deliberately set itself apart and outside the Constitution make amendments to the Constitution? Legally it cannot. Its position on the relative merits or demerits of the various constitutional amendments proposed is, therefore, irrelevant because the means to accomplish any amendments is legally unavailable to Parliament at this juncture due to the illegality of the national legislature.

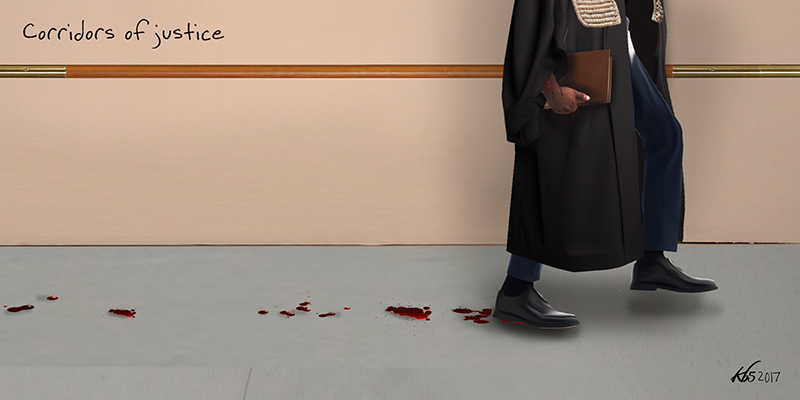

By promoting national dialogue on constitutional amendments, the political leadership – with the complicity of the Chief Justice and religious, business and civil society leaders – are attempting to lure the public into a conspiracy to commit further illegalities.

Kenya’s leadership class is fully aware of Parliament’s illegality and the constitutional crisis. In addition to the official position of the Office of the Attorney General, the jurisprudence from various courts and a petition seeking to dissolve Parliament pursuant to Article 261(7) has been pending before Chief Justice Maraga since September 27, 2017. By promoting national dialogue on constitutional amendments, the political leadership – with the complicity of the Chief Justice and religious, business and civil society leaders – are attempting to lure the public into a conspiracy to commit further illegalities.

The only way to legally amend the Constitution is through a constitutionally compliant Parliament. The legal impediment to constitutional amendments is Parliament’s unconstitutionality; curing that illegality is the first step to legally amending the Constitution.