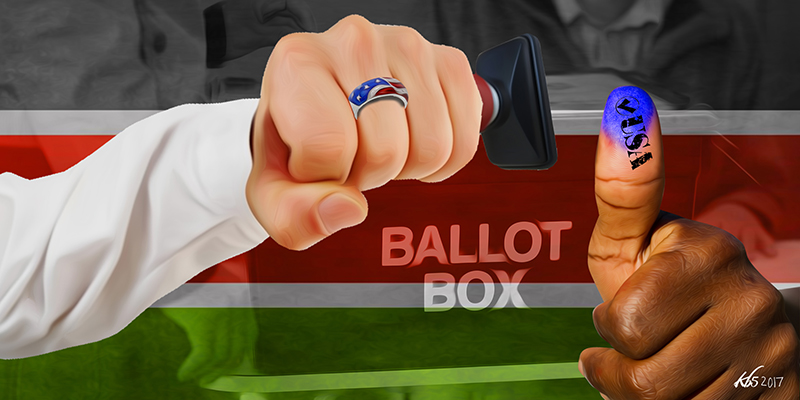

After Raila Odinga boycotted the October presidential repeat election in Kenya, he declared his intention to swear himself in anyway. The Supreme Court had annulled the August 2017 election and the same suspect electoral officials and technology firms had just perpetrated what Odinga’s NASA coalition saw as yet another fraud. Given that Odinga had been rigged out in 2007, and probably in 2013 as well, the boycott shouldn’t have come as a surprise. But swearing himself in?

Washington is clearly nervous. In November, Odinga discussed his predicament with members of the US Congress, and in December, newly appointed US Assistant Secretary of State Donald Yamamoto rushed to Nairobi and urged Odinga to call off the swearing-in ceremony and “focus on his legacy” – a polite way of saying, “Please retire”.

Odinga’s swearing-in is now scheduled for January 30th and the Americans have threatened him with unspecified sanctions. But many Kenyans wonder why they don’t sanction President Uhuru Kenyatta, whose electoral commission engaged in foul play and whose security forces killed scores of innocent people. Isn’t this at odds with America’s professed commitment to democracy?

Not really. When Harry Truman, standing in the shadow of the atom bomb, launched America’s first foreign aid programme in 1952, he told the American people that their greatest gift to other nations would not be their technology and know-how, but “the true secret of our American revolution…that the vitality of our science, our industry, our culture is embedded in our political life…that only free men, freely governed, can make the magic of science and technology work for the benefit of human beings, not against them.”

Odinga’s swearing-in is now scheduled for January 30th and Washington has threatened him with unspecified sanctions. But many Kenyans wonder why they don’t sanction President Uhuru Kenyatta, whose electoral commission engaged in foul play and whose security forces killed scores of innocent people.

But even as Truman was delivering this inspiring message, State Department officials were fretting about Europe’s imperial retreat from the African continent. George Kennan, who helped shape early Cold War foreign policy, complained privately that non-Europeans were “impulsive, fanatical, ignorant, lazy, unhappy and prone to mental disorders and other biological deficiencies,” writes historian James Hubbard in The United States and the End of Colonial Rule in Africa. The mixture of Westernised and exotic backgrounds created “embittered fanatics” who would easily succumb to Soviet-inspired demagoguery, Kennan wrote in his diary. “We have to get over our complex that every little black or brown man with a tommy gun in his hand is automatically a 16-carat patriot on the way to becoming the local George Washington,” echoed Eisenhower’s foreign policy adviser C. D. Jackson. In 1952, the US even opposed including an article on government by the will of the people in a draft United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Vice President Richard Nixon put it bluntly: Africans could not be democratic, having only emerged from the trees 50 years earlier.

The Americans would have greatly preferred that the Europeans continue handling the Dark Continent through their empires, but decolonisation was inevitable. The fate of the French, who were being pummeled in Algeria, provided a lesson for what was in store for imperialists who overstayed their welcome.

In 1960, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan spent two months touring Her Majesty’s African colonies. Looking back on a decade of pro-independence riots in Malawi, Uganda, Kenya and elsewhere, and fearing a string of Boston Tea Parties across the globe, he drafted his famous “Winds of Change” speech announcing the British Empire’s imminent dismantling. By 1965 the Empire had virtually disappeared.

Flummoxed as to what to say to a visiting Ethiopian diplomat, President Dwight Eisenhower mentioned that he’d heard that African elephants, unlike their Indian cousins, could not be tamed, a remark the visitor considered racist.

Washington realised it needed an Africa policy quickly. Diplomats were convinced that the Soviets were already “wooing” African independence activists. This wasn’t true, according to numerous national security estimates; most emerging African leaders were concerned with internal and regional politics, and wished to remain neutral in the Cold War. But the Americans saw Marxist conspiracies in every trade deal or contact between African leaders and the USSR and they quietly panicked about what this might mean for control of the newly created United Nations and world supplies of diamonds, gold, uranium and other strategic resources.

However, Africa’s soon to be 40-plus independent nations, countless tribes, and numerous clans posed a vexing policy conundrum because few in Washington knew anything about them. To Under Secretary of State George Ball, their names seemed like “typographical errors.” Moreover, America’s treatment of its own black population posed serious diplomatic problems. Flummoxed as to what to say to a visiting Ethiopian diplomat, President Dwight Eisenhower mentioned that he’d heard that African elephants, unlike their Indian cousins, could not be tamed, a remark the visitor considered racist.

Eventually, Eisenhower arrived at a solution. America would pursue a “two track” approach, professing support for African self-determination in public, while giving African leaders a stark choice: Side with us or the Soviets. If with us, expect lavish foreign aid and a free rein to control your own people by any means, including harsh repression. If with the Reds, expect no US military or development aid, and risk being overthrown or assassinated by covert CIA operatives or rebels backed by them. In due course, African leaders deemed ambivalent about protecting US interests, including Congo’s Patrice Lumumba, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Uganda’s Milton Obote, were shown the door, if not by US operatives, then by those of her allies. Meanwhile, Washington looked the other way when tyrant-allies like Zaire’s Mobuto Sese Seko and South Africa’s apartheid leaders oppressed, tortured and killed their own citizens.

After the Cold War ended around 1990, the US cautiously began withdrawing support from dictators and began supporting multi-party democracy in some African countries, including Ghana, Zambia, Malawi, Tanzania, South Africa, and eventually, Kenya. But some countries, including Uganda, Ethiopia and Rwanda, would not make the democracy list. Instead, their militaristic leaders would become America’s new allies in a bloody campaign to rearrange the balance of power on the African continent, and hold back what Washington saw as the growing power of political Islam which had replaced the Soviet Union as its public enemy du jour.

Officially, US policymakers would say Africans needed to fight their own battles; in reality, Africans—particularly Ugandans, Rwandans and Ethiopians – would be fighting ours.

The stakes were high – an estimated $24 trillion worth of unexploited oil, gold, diamonds, cobalt, uranium, and coltan, the raw material for cellphone and computer chips, most of which lay underground in Congo, that vast, poorly governed country at the heart of the continent. During the Cold War, these resources were kept out of Soviet hands by US-backed thugs such as Mobutu and South Africa’s militaristic apartheid regime. But the fall of the Berlin Wall shifted the kaleidoscope, turning former enemies into friends and vice versa. South Africa would soon be free, and the aging and increasingly addled Marshall Mobutu was growing closer to Sudan, where a new Islamist government was recruiting militants throughout the Middle East to expand their own sphere of influence.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, virtually every major war on the African continent has been instigated by at least one of Washington’s three main allies: Uganda, Rwanda and Ethiopia. Not one of these countries has ever held a free and fair presidential election. Yoweri Museveni has ruled Uganda since 1986; the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) has clung to power since 1991; and Paul Kagame has been Rwanda’s de facto leader since 1994. Many local elections in these countries are rigged as well. Nevertheless, every US administration since President Ronald Reagan’s—including, sadly, Barack Obama’s – has lavished weapons, financial assistance and praise on these tyrants, and helped them cement their grip on power.

At first, Kenyans, who’d suffered mightily under their own Cold War dictators, were spared Washington’s machinations. But as the crisis in Somalia escalated after the bitter 2006 US-supported Ethiopian invasion, Washington seems to have taken a greater interest in who’s running the country. Commercial interests in Kenya, particularly defense and construction contracts, may also be on US diplomats’ minds.

Every administration since President Ronald Reagan’s—including, sadly, Barack Obama’s – has lavished weapons, financial assistance and praise on the tyrants in charge of these countries and helped them cement their grip on power.

In December 2017, an aide to Rex Tillerson summed up this cynical policy in a leaked memo, which explained to the novice Secretary of State that “we should consider human rights as an important issue in regard to US relations with China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran,” but not in countries that advance America’s military or financial interests. Many Americans were shocked by this hypocrisy.

Then, the whole world was shocked when President Donald Trump reportedly referred to African nations as “shithole” countries. Perhaps Mr. Trump should ask himself how these shitholes came to be. While African leaders deserve much of the blame for the corruption, poverty and war without end that prevails in the Horn and Great Lakes regions, Washington has also had a hand in the mayhem.

[1] https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/usip-special-report-zaire. See the third point under “Zaire and its neighbors”.

[2] https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-lost-hopes-for-south-sudan; https://www.ctvnews.ca/features/as-millions-flee-south-sudan-how-is-canada-helping-1.3741658