Seven years after the promulgation of the 2010 constitution which forbids gender discrimination, Kenyan women are still not receiving equal pay for equal work done.

They are also being short-changed when it comes to getting equal pay for work of equal value.

That means they have less spending power, have less to save and even less to put aside for their retirement meaning that many are in later life forced to be dependent on their families.

According to the World Economic Forum report 2017, a Kenyan woman is paid Sh55 for every Sh100 paid to a man for doing a similar job.

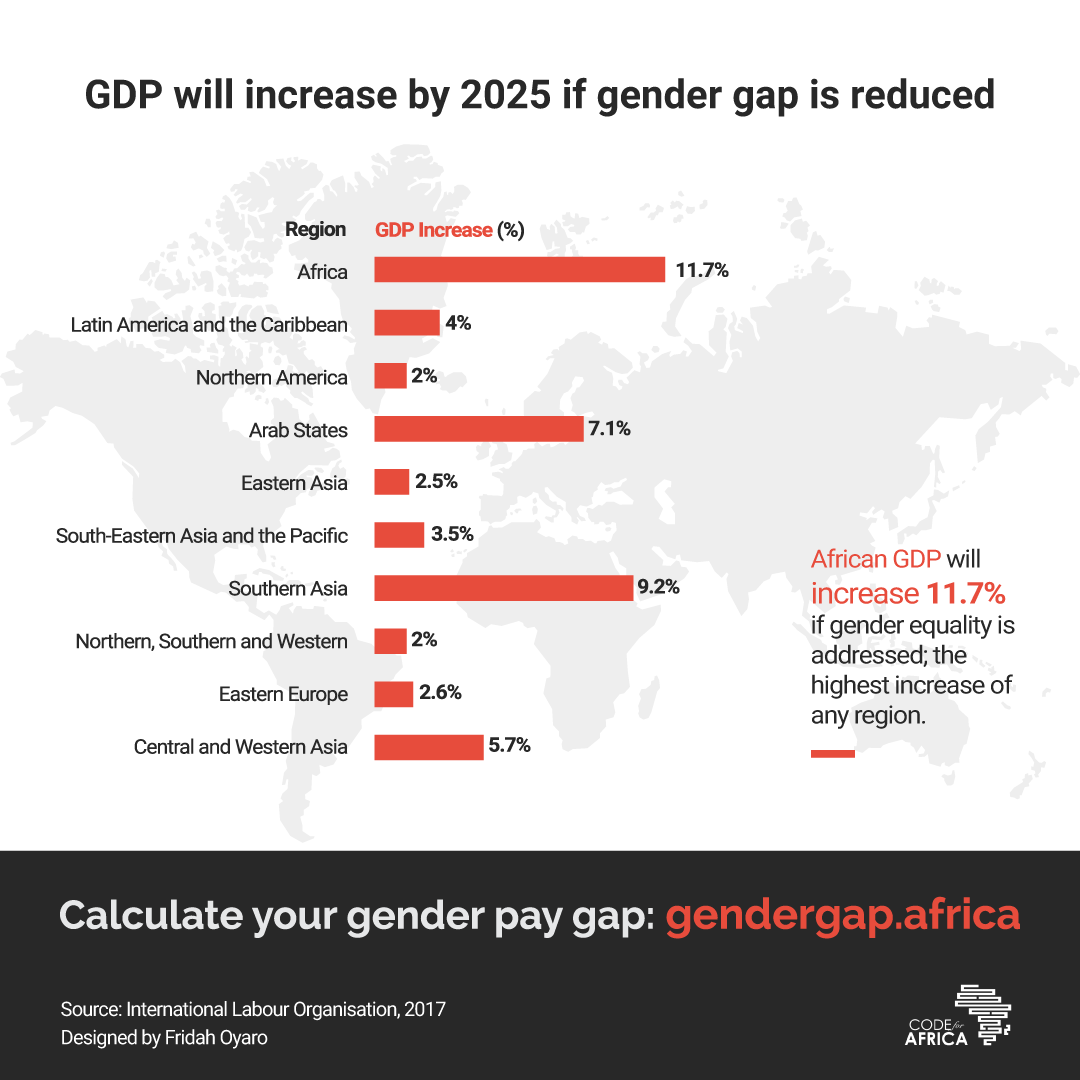

The Human Development for Everyone report released in March 2017 and compiled on the basis of estimates for 2015 indicated that women make up 62.1 percent of the total labour force compared to 72.1 percent of the men surveyed during the same period. The same report indicated that while Kenyan men earned an estimated gross national income (GNI) per capita for males of $3,405 (Sh350,715) in 2015, this was far higher when compared to the $2,357 (Sh242,771) for females. The GNI per capita reflects the average income of a country’s citizens in dollar terms. And because they earn less than men and are less likely to control land, women pay less in taxes and are less likely to be leading in entrepreneurial activities.

So, why do women continue to earn less than men?

The Learning and Development Manager at NEST – a multidisciplinary group working with film, fashion, visual arts and music – Dr Njoki Ngumi says the general lower value ascribed to women translates everywhere, especially in the formal workplace. Dr Ngumi also heads the HEVA Fund, which invests in the transformative social and economic potential of the creative economy sector in the East African region.

“This (the formal workplace) continues to be a site for consolidating power, building wealth and amassing influence outside the home and we have been socialised to see women as not needing this access as they are supposed to be catered to by the resources of men in their lives,” said Dr Ngumi.

One of the biggest hindrance to equity in pay can be attributed to women having to take time away from work to have babies or what has been described as the ‘child penalty’ (the percentage by which women’s pay falls behind men as they start bearing children.) A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research on Children and Gender Inequality conducted in Denmark and released in January 2018 indicated that having children creates a gender gap in earnings of around 20 percent in the long run. This gap is driven in roughly equal proportions by labour force participation, hours of work, and wage rates. The study showed that while earnings did reduce with men after having the first child, the drop in earnings for women was steeper and more visible. While similar studies have not been conducted in Kenya, motherhood has a direct impact on women’s earnings. Working mothers experience systematic disadvantages in pay, perceived competence, and benefits relative to childless women. Few companies are yet to provide breastfeeding stations for nursing mothers or make their workplaces “mother and baby friendly as stipulated in the Breastfeeding Mothers Act which was enacted by Parliament in June 2017.

In Kenya, as in most developing countries, the value placed on women’s labour such as nurturing and being supportive of their families and children are not regarded as having a high economic value. Women have to take time out to attend to these ‘undervalued’ activities, thus a perception that they are being less loyal to the company and are more likely to exit the workplace in their childbearing years or be given less opportunities to advance to roles with greater corporate responsibilities.

Even though this may not be true in some cases ambition in women is particularly pathologized, notes Dr Ngumi and as such employers almost tend to see it as their duty to ensure that women will be available for home duties, while assuming that men have no such duties. Even in instances where women are qualified, Dr Ngumi observes that women tend to be hired for ‘emotional labour’ which then makes the workplace ‘happier’ and since this is not skills based but rather based on women’s ‘innate characteristics’ they are subsequently paid less.

While part-time work may not amount to much wage difference per hour worked it, however, always results in the woman bringing home less money by the end of the month.

Many women with young children may opt to take up temporary jobs or those that offer them more flexible working arrangements and as a result, end up missing out on earnings growth associated with staying in a permanent job. They may also opt to work for smaller companies which are more amenable to giving them flexible working hours instead of big companies where opportunities for career growth may be more and salaries may be higher. Part-time employment refers to regular employment in which working time is substantially less than normal.

“I think that the pay gap is such an entrenched concept that flexitime- which is still more an exception than a rule – does not contribute as much to the pay gap as we think,” she said.

For Dr Ngumi the real issue being that in general the workspace has not had time to get into the true understanding of delivering on deadlines from home without the supervision of a senior, and the assumption is that remote work for middle cadres and people with more tangible deliverables is not real work.

She said the freelance economy – while offering varied freedom like time – also creates a space that denies the worker the benefits of a full umbrella of cover by an employer, or the safety controls of a formalised work structure. All these combine to disadvantage women with small children further.

Education and gender pay gap

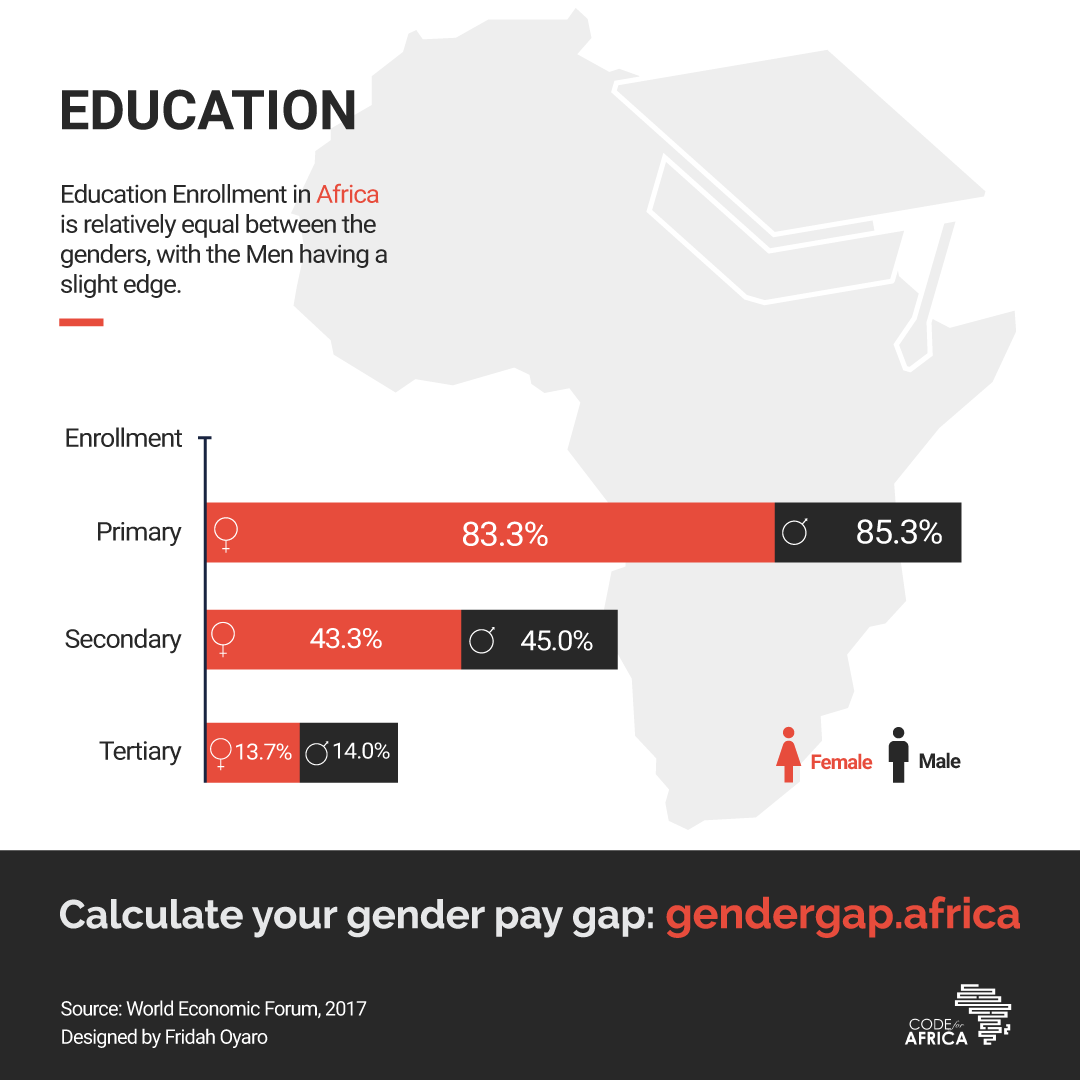

Education plays a major role in the gender pay gap with women more likely to get an average of about 11 years of schooling compared to men – 11.4 years. While at the primary entry level the gap between boys and girls is negligible, this becomes wider due to early marriages and other cultural biases which tend to favour boys over girls.

“Gendered games we introduce to children in early childhood illustrate the roles we see men and women playing in society. Boys are encouraged to build new, imaginative things and go on adventures, while girls are encouraged to arrange things neatly doing domesticated tasks and aspire towards being beautiful and dressing well,” said Dr Ngumi.

In Kenya, every person, including women, have the right to fair remuneration. Women and men have the right to equal treatment, including the right to equal opportunities in political, economic, cultural and social spheres.

“The State shall not discriminate directly or indirectly against any person on any ground, including race, sex, pregnancy, marital status, health status, ethnic or social origin, colour, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, dress, language or birth, mental status or HIV status.”

What can be done to reduce the gender pay gap?

Companies or branches of industry should publicise the wages/salary scales to make it easier to highlight unmerited wage differences.

According to Dr Ngumi, employers should provide on-the-job training or work-related upgrading courses specifically to cater for their women employees and introduce mandatory quotas for each gender in the non-executive boards of listed companies and state parastatals.

“One of the reasons that women get paid less than men is that there are fewer of them in senior positions. And since companies prefer to appoint executives from those who have served on boards, they would have a gender diverse pool to choose from if there were more women serving on boards. This needs to be well thought out before implementation as such appointments may cause friction within institutions or companies.”

Implementation of the two-thirds gender quota clause in the constitution.

The election of 23 women in the National Parliament during the 2017 election was a slight improvement from the 16 elected in 2013. This might be an uphill task as there is clearly no political will to implement this as can be seen from President Uhuru Kenyatta’s Cabinet appointments.

The government should enact policies and Parliament enact laws that would make it easier for women to not only own and inherit land but also enable those who own land to access credit.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this piece had attributed a quote to Dr Njoki Ngumi. The quote was misplaced and The Elephant has taken the earliest opportunity to correct this.