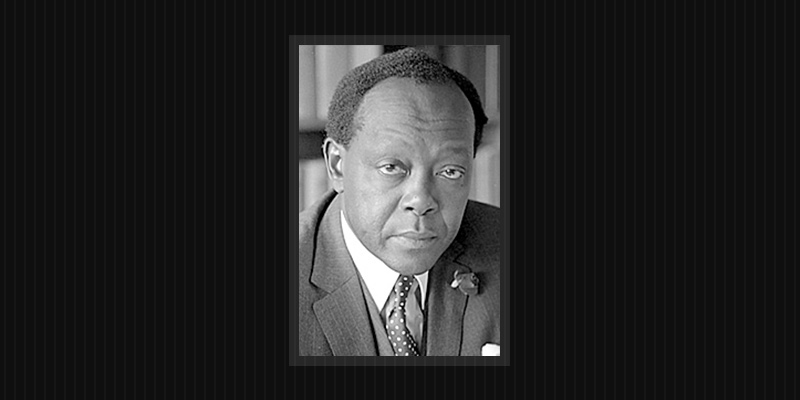

A lot has been written and a lot more will be written about the late Charles Mugane Njonjo who has passed away. I would like to tell my own personal story. I never knew him as a bureaucrat or politician. Indeed, our paths crossed immediately I left high school in 1983. Together with colleagues, we had written a play and planned to perform it for the public. We searched our minds for a public figure who would agree to come as guest of honour on opening night. We sought someone who would attract public attention to what we were doing, but more importantly for us 17-year-olds, someone who would agree to show up. Charles Njonjo’s name was all over the news at the time. His political career had just been truncated amid the prolonged political drama of the “traitor affair”. He was a figure of great public fascination for a variety of colourful reasons. We also had the names of other public figures on our list and I was tasked with reaching out to them.

Frankly, I wrote to Charles Njonjo not expecting to hear from him. He replied immediately, though, and accepted the invitation to be guest of honour at the opening night of our play, The Human Encounter, at Saint Mary’s School in Nairobi. Once he accepted the invitation, we excitedly proceeded with preparations for the opening night. A few days later, however, we were informed that, unfortunately, the authorities had deemed Mr Njonjo’s presence at our event unacceptable and the decision was not negotiable. I informed my colleagues and we decided that since we had worked hard on the production we would obey the orders from above and proceed with our play without Mr Njonjo. There was no need for a fuss. I then had the embarrassing duty of disinviting Mr Njonjo when he had already accepted to be our guest of honour.

I spent a whole night drafting the letter and in the end, my late father told me not to agonise excessively, “Njonjo likes to be told the truth directly.” So I wrote the disinvitation letter as clearly and as respectfully as I could. I asked a friend of his to pass it on to him and did not expect to ever hear from him again. The message I received promptly back surprised me. Njonjo expressed his deepest appreciation for the invitation and explained that he fully understood why it had been withdrawn. He asked that we remain in touch. I was deeply relieved. Over the years, he would reach out to me through family and friends and we would interact jovially, remembering the letter I had written retracting his invitation as guest of honour. “No one has ever done that to me,” he would joke over tea.

In the early 1990s, as political pluralism was returning to Kenya, violence broke out in Nyanza, Western and Rift Valley provinces. At one point, hundreds of thousands of Kenyans were displaced as our elites arm-wrestled for power. I travelled to Laikipia and then to Burnt Forest and was aghast at the state of the internally displaced that had been forced from their homes by the violence. Together with Dr David Ndii and Mutahi Ngunyi we launched the “Kenyans in Need” appeal. The then chief editor of the Daily Nation, Wangethi Mwangi, gave us free advertising space to mobilise resources for the displaced – especially those in Ol Kalou who had been evicted from Ng’arua in Laikipia. The late Archbishop Nicodemus Kirima of the Archdiocese of Nyeri agreed to use the relief infrastructure of Catholic Church to distribute any donations that came our way. Laikipia fell under Kirima’s remit.

The response to the appeal was surprising in its scale. People donated second-hand clothes, books, shoes and cash to the appeal. We received around KSh1 million worth of donations over the following months. We delivered the first batch directly to the philosophical Archbishop Kirima at his official residence in Nyeri, unique because of its specially built library full of the books he clearly loved. Our biggest and most consistent donor throughout the entire enterprise was Charles Njonjo. He was not keen to have his name mentioned but we would sit at his home drinking tea and reflecting on the political situation in the country.

When I joined government in 2003, Njonjo remained one of my steadfast providers of moral support. When news broke that I had been moved from the Office of the President to the Ministry of Justice, the first call I received was from Charles Njonjo. “You’re going to resign immediately, aren’t you?” he asked in his typically direct way. In the end, I didn’t. I sometimes wistfully recall his advice at the time. We kept in close touch.

When my situation in the Kibaki government went belly up in 2005 – as he had predicted to me many times – and I found myself in exile, Charles Njonjo became an even more steadfast friend. He stayed in touch and whenever he called, he would always enquire about my personal circumstances. He was a most interesting person in that way, loyal to his friends to a fault. Once you were his friend, he stood by you no matter how atrocious the circumstances. He would call to tell me he was coming to London and we would spend the day together simply walking the city, chatting and drinking tea. Back home I found out he was in constant touch with my family, offering moral and any other kind of support that might be needed.

When I returned from exile, one of the very first people to invite me for tea and a catch-up was Charles Njonjo and we took up from where we had left off in 2005. His observations on politics and about certain politicians were often wryly hilarious. His capacity to read people accurately was something I learnt. We would sit in his Westlands office and I would seek his opinion on this or that political interlocutor and in typical fashion he was always direct – “solid fellow”; “believe only half so-and-so says”; “take that one seriously”, etc. He was particularly dismissive of ethnic chauvinists and insisted that they held Kenya back in fundamental ways.

Charles Njonjo and I kept our friendship quiet. In part, this was because some of his diehard enemies were also my very good friends – the late legal giant Achhroo Ram Kapila SC among others. So, we didn’t discuss his enemies; he advised me on mine. Much will be written about Charles Njonjo and even though there was much we totally disagreed on politically, the Njonjo I knew since I was a teenager was a man of his word. He was a dear friend in ways I have never been able to share. There is not a personal problem that I raised with Charles Njonjo that he didn’t immediately seek to solve in his no-nonsense style. Njonjo could be a very funny man, full of jokes and insightful observations without a taint of bitterness. To me he was funniest when he joked in Gikuyu, which some people thought he couldn’t speak.

As I have said, much will be said and a lot will be written about Charles Njonjo. The Charles Njonjo I knew was a steadfast friend and a man of his word. I have lost a dear friend and wish his family succour as they mourn him at this time.