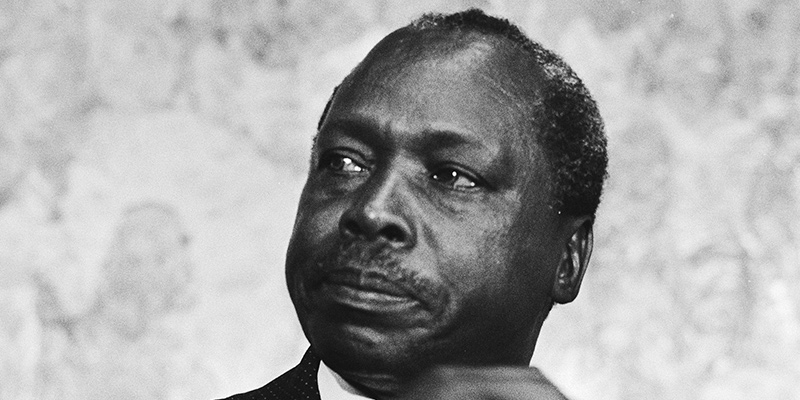

We are poor because we are not in government. These words, said by my grandfather, my father, my uncles, and later by my compatriots at various stages of life, have stuck with me. They were simple enough words, but their weight was hidden in the everyday realities of the men and women whose communities were perceived as the opposition, viewed as enemies of the government. That government was one man. President Moi. For 24 years he dominated the national psyche, changing people’s lives the way a hyperactive child switches between television channels.

If you caught Moi’s attention by doing something as mundane as composing a song in his name during the national drama festival, you could become rich overnight. Not being in government was tough. This is because the Kenyan government has been set up to strengthen ethnic dominance, rather than to build national cohesion. I grew up at a time when my community was strongly represented in the opposition. This made us fair game for the government of the day.

Like many Kenyans, I was anxious about joblessness. I was young when my uncle Ben graduated from university in the nineties. His stories of desperation and despair for a job, and his death four years after graduation, were a constant source of anxiety as I studied at Kenyatta University. Like many graduates, Uncle Ben did not have connections in Moi’s government. Our people were not in power. Even the local district officer in my hometown was from the president’s tribe. And the local administration policemen too. The entire police force spoke the dialect of a single tribe. The president’s tribe. The police force was supposed to mirror the face of the nation. That was on paper. In reality, it was the face of ethnic dominance, an expression of the desire of the ruling elite to control power.

The public kept up hope nonetheless, and every year, young men and women across the country would be taken through a grueling marathon of physical exercises in the hot sun, running until they were broken. The few who would make it back to the stadium, sweating, almost fainting, were not guaranteed success. They could still be disqualified because of a missing tooth.

In a country where dental care is difficult to access, replacing a tooth is not something that is within the reach of the poor. Uncle Ben ticked all the boxes. He was an athlete. Six feet and three inches tall. Perfect teeth — except for the nicotine stains from smoking to relieve stress. But he didn’t make the cut. Year after year. My father said it was because we didn’t know anybody important in government. That seemed to be the only pathway to employment in the late 80s and 90s when the economy was shrinking under Moi’s stewardship.

Moi’s twenty-four years at the helm ended in 2002. 2001 had been a pivotal year in Kenyan politics and Moi’s reign was coming to an end as I was coming to the end of my second year at Kenyatta University. The fear that Moi would be president for life was wafting away like a bad smell. We were ecstatic. We were also aware that the late Prof. George Eshiwani, our vice chancellor then, did not share in this excitement. His exit was perfectly aligned with Moi’s. State agents were no longer at Prof. Eshiwani’s disposal and student leaders who had challenged him in the past started showing up on campus. Word was also going around that lecturers who had been thrown off campus like homeless people, were agitating to return. One of them, Prof. Kilemi Mwiria, would later head the education docket in the new government. If Prof. Eshiwani did not leave willingly, we would force him out. We forced him out.

President Kibaki took the reigns of power in 2002. Unlike Moi, he was a closed man. We waited with bated breath to see how he maneuvered. Up to then — and still to this day — only two tribes had ruled over the other forty-plus tribes. And like in many African countries, the elites from these two tribes had been awarded plum positions and government contracts. There was entrenched ethnic dominance. I was born on the wrong side, the opposition side. The side that attempted a coup d’état to overthrow President Moi.

Adhiambo, one of the soldiers involved in the attempted coup, lived less than five miles from my maternal grandfather’s home. He was released after many years in jail. People gossiped that he came back a shadow of his former self, whispered about his inability to have children. And that sometimes he talked to himself. He settled in his father’s shop. I walked by that shop a few times with one of my uncles just to get a glimpse of the man. To see just how much his body had been broken at Kamiti Maximum Prison.

Moi’s daily presence in our house — for a minimum of fifteen minutes during the seven o’clock news and for another fifteen minutes during the nine o’clock news — was a source of tension. When home, my father would demand that we switch off the television. My mother on the other hand would plead with him to allow us to watch Moi. We young ones enjoyed watching the beautiful schoolgirls and their teachers dancing for Moi. They seemed to be in a bubble of security and infectious happiness. We marveled at how privileged these children were that Moi would visit their schools to fundraise for development projects. How lucky they were to be on TV, to take pictures with Moi.

My father hated the obsession with the president, abhorred the spectacle of grown men and women pontificating about Moi being their father and mother. He hated it even more when the local chief came to our family’s tailoring shop, a small business my father had set up to supplement the family’s income. The chief was enforcing an order from the district commissioner. Word was that Moi would drive through our rural town on his way to nearby Rongo, the hometown of one of his new friends from my community. He had risen quickly through the ranks to become a powerful minister of internal security. It was rumored that he was the custodian of a secret.

Moi was on his way to open the massive Seventh Day Adventist Church that his new friend had constructed in Rongo. A gift to his people. And a sign of gratitude to God for his newfound power. Potholes on the Kisumu-Kisii-Migori road were hastily filled with red volcanic soil and a thin layer of tar. There were also security meetings where the local chiefs were instructed to ensure that the local KANU offices had a fresh bright coat of red paint with the party symbol, a red cockerel, clearly visible. The show of loyalty had to be explicit in these opposition zones.

In addition, local businesses, like my father’s tailoring shop, needed to clearly display Moi’s image on their walls. When the chief and his men came, my father was not there. They confiscated the sewing machines and demanded that my father collect them with proof that he had Moi’s framed photograph on the wall of his shop. The local KANU offices were selling framed portraits of Moi at a profit. Who didn’t love the president? Who didn’t want Moi following them with his warm reassuring eyes as they went about their business?

Uncle Ben took a newspaper, cut out Moi’s image, stuck it on a cardboard and framed it. I expected the chief to be furious but he relented. His two sons were in the school where both my parents were teachers and he always needed my father’s help with school fees or a contract to supply maize and beans. Also, why start a fight with my father when there was no chance Moi would see this image of himself plastered onto cardboard? After all, all businesses would be closed when Moi passed through so that people could stand by the roadside and wave to him.

I remember Moi’s convoy driving through my hometown at high speed. I remember the disappointment on people’s faces as the convoy disappeared into the distance. I remember people sighing and trying to console themselves: “I saw his car”. “But which car was he in?” “The one with the flag”. “But there was more than one car with a flag”. “Don’t worry, he will stop on his way back,” our school principal consoled us. He said that Moi had been busy, that he needed to keep time for his next appointment. He reminded us of the need to keep time like Moi. We had waited for Moi for over five hours. The school choir had run out of songs of praise for Moi.

Later that evening, my father bemoaned the time wasted composing and practicing songs for Moi. The time wasted standing in the sun, the school hours lost.

In the early 90s, with the rise of opposition politics, a circular was sent to schools instructing teachers to shave their beards. The government wanted presentable teachers. Also, people with beards had been seen to be sympathetic to the opposition as well as harboring Marxists ideas in parliament. “The six bearded sisters”, a group of opposition members who had mustered the courage to criticise Moi, were under government surveillance. My father was made aware of this circular by the head teacher of the school where he taught. He was instructed to shave. The government was not only controlling freedom of expression. It was controlling freedom of personal appearance. My father protested. Word started spreading around that teachers were getting shaven forcefully by the local administration. The Nyanza provincial commissioner was reported to have supervised one of these forced beard shavings. I didn’t see my father much during those days. He would play cat and mouse with the school administration, teaching his classes before going into hiding in our rural home.

Moi was a good man. He did not drink alcohol. Not like Mobutu Sese Seko. The only beverage that would corrupt his body was coca cola. Which he also drank in moderation. Moi was also in church every Sunday, where the pastor would pray for his good health so that he could continue guiding the country away from the unpredictable hands of the opposition, lest Kenya descend into chaos like our neighbour Uganda. Or Sudan. Or Congo. Or Rwanda. Or Somalia. Or Sudan. And occasionally we would also get free milk at school. We would carry it home, or drink it under a tree during break. With our stomachs full of milk, we knew we were lucky because Moi loved children. Otherwise, why did he work so hard to provide us with milk?

In 1992, when I was ten years old, uncle Ben came home abruptly. Unannounced. Dr Robert Ouko had been killed. He had been very loyal to Moi. Uncle Ben and my father were glued to the television screen as riots engulfed the streets of Nairobi and Kisumu. Many people died in Kisumu, Dr Ouko’s hometown. My father and Uncle Ben seemed defeated. We are poor because we are not in government. And when one of us gets into government, they kill him. It was hard to reconcile the images of Moi the all-loving father of the nation, Moi the God-fearing, humble servant with the Moi accused of heinous human rights abuses. And to reconcile this with the message from my pastor every Saturday that all leaders come from God and that, therefore, God had given us President Moi for twenty-four years.