Have you seen this mirage, every five years, when you are thirsty for change? Just when you think you’ve reached it, it disappears. Then, as if on cue, campaigns for the next cycle start almost immediately. You get primed with promises for the next cycle. You follow it with your eyes, your whole being, until your throat is so dry, your heart stops pumping and you die. And your children continue on this loop. Every five years since 1963, but much more since 1992.

Let us talk about James. In 2008, while at a small rural hospital in Siaya, I met James. He was a tall lanky man with a shy smile. He kept this smile hidden well within his soft demeanor. James had very white eyes. I looked through them and saw a few things I saw in December of 2007. Bad things. The things that arrived with buses and trucks, with women and children and men carrying their life savings in a few small polythene bags. Barefoot. Having run from Nakuru. Naivasha. Kiambaa church. James’s eyes were extra white, clear with memory. He had run from these things to his rural home in Siaya.

James was a Kenyan man. He was thoroughly steeped in this water of Kenyan manhood. One that decreed that as a man, you talk tough even when you are in pain. No, it is not painful. I am alright. Pain is a weakness, unless you are inflicting it on your wife. Or children. Or members of another tribe. Or your constituents. Or the opposition. And other people’s pain becomes your strength. A few times I would spot James walking alongside the Siaya-Kisumu road headed to Ng’iya dispensary, a small rural health facility doing a lot with very little resources to provide services in an area with serious healthcare needs. I would slow my car down, pull over by the side of the road and offer James a ride. During one of our chats, I asked James what was behind his commitment to this long walk to Ng’iya dispensary. What made him wake up every morning to hit the hot tarmac for five kilometers to volunteer his time at the local patient support center for people with HIV? Was he one of those people doing it for God, for religious convictions?

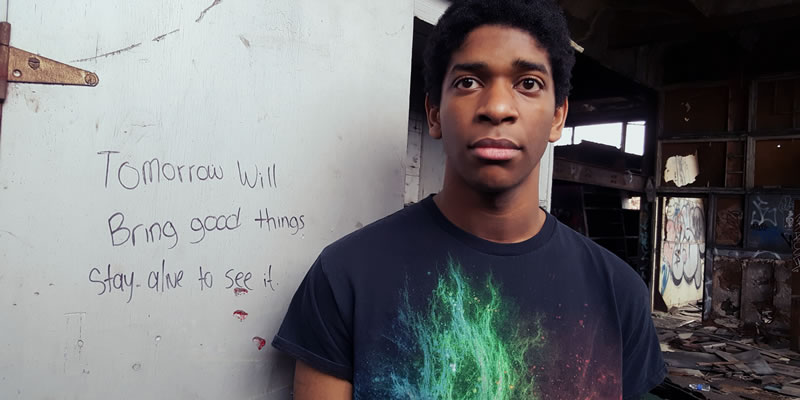

Then I learned it. I have seen it in the face of farmers, waiting on the rain god. Seeds in the ground. Eyes fixed on the clouds and a prayer firmly in their chest. Willing rain to fall. It was hope. Hope amidst every challenge in life. Hope was getting this man out of bed to do something for he believed in; something for humanity. He moved his seat back, to allow his frame to fit into my small Nissan. It was hope. He had hope that things would be change. He had hope that the government would keep on sending supplies of anti-retroviral drugs (ARVs) for HIV patients. Hope that the government would hire trained staff to take care of patients at Ng’iya. Hope that patients would adhere to their ARVs treatment regimens and get better. And stronger because it would rain and crops would grow and food would be abundant. And everyone would do well. This hope that James had, was one of the most important, though unseen pieces in a social contract between ordinary Kenyans and Kenyan government.

James was hoping that the government, right from the county ministry of health, to the cabinet secretary of health, to the president, would fulfil their end of this social contract to keep these patients alive. James was committed to walk ten kilometers daily to volunteer his energy and time while hoping that everyone in this long chain did not betray this social contract. There was only one problem. James and I knew that evidence did not always support the wave of hope he was riding on. There was blatant neglect by people in the long chain of bureaucratic command and on many occasions, patients had come for these lifesaving ARVs on scheduled days and James had sent them back, and had told them to keep on checking. Rudi tena baada ya mwezi moja. Hakuna dawa. They needed to come back in a month. The risk of them moving between stages of HIV notwithstanding. They still had to dig deep into their purse of hope, even when there was nothingness, because in the absence of nothingness, you anchor on hope. Hope was the only thing to live on when the government was in a quarrel with the medical workforce over salary increases and the local nurse, pharmacist and clinician would not show up to work over extended periods of time. But James, along with other Kenyans have hope. That one day, they will jump this puddle and land on the dry Promised Land.

One day I went to the clinic and saw James in the hospital bed with a drip in his arm. He had an infection and had gotten severely dehydrated. He looked exhausted, his eyes now white with exhaustion. I knew at that point that this hope was probably what kept James going. And this hope could also kill him. The hope and goodwill of poor Kenyans is the currency that has kept the criminally negligent government of Kenya afloat. People continue to die for this hope when all evidence points to a state of hopelessness.

In 2007 people came out to vote, bursting with hope for change. People would come out every election cycle until the last election in 2017. The government having studied the hopeful masses carefully, militarized every corner of the republic. This hope could not be allowed to roam freely in the streets. It had to be confined within the realm of state control.

But really, what else is a poor man and woman left with, when all hope is gone? Nothing.

A sewer

Unaruka mkojo, unakanyaga mavi.

A little over a decade ago, the Kenyan hip-hop group P-Unit released the song “Una”, a collabo with featuring DNA, another Kenyan artiste. It was a club banger and I wouldn’t blame you if all you remember about it was its danceable beats, as you partied in the club or sipped on your drink waiting for the traffic jam to clear. People need some relief, a pit stop, and lull before a storm of reality of being Kenyan.

But having recently listened to it again after many years, I believe this song deserves a second look because it has multiple subliminal messages that capture the mess Kenyans have been thrown into by our leaders.

One of the most prominent lines in P-Unit’s song is unaruka mkojo, unakanyaga mavi. This can be loosely translated as — you jump over a puddle of piss right into a pile of poop. Nothing can capture the current state of Kenya like this song. We, the people, jumped a whole ocean of piss, only to land face first in a sweltering sewer of sorts. Imagine that for a minute. My submission is, P-Unit foreshadowed the current state of affairs in Kenya.

In 2002, Kenyans summoned all the willpower in the world to reject President Daniel arap Moi’s torturous regime. They elected President Mwai Kibaki against a well-funded state machinery propped by Moi and his cronies. Kibaki was in a wheel chair, incapable of the daily rigors that come with presidential campaigns in Kenya. He would win against all odds. Jubilant Kenyans hoisted him high, leaped over the puddle of piss with him with on their backs. Kenyans deliriously entered a new chapter. Kibaki was probably the first opposition candidate to be elected while in a wheelchair in the history of African politics. It didn’t take long for him to remind us, Kenyans, of what he thought of us.

Five years later, Kibaki would preside over one of the bloodiest election periods in Kenya. Surrounded by other cronies, Kibaki made sure he was sworn in as president at night. No ceremony. Just a rush to consolidate power and access state machinery in the form of militarized police known to unleash extreme levels of brutality in opposition areas.

While this was happening, P-Unit’s song, Una, would soon be blasting ominously at the background. Kenyans, in their efficient way, had jumped from Moi’s unending ocean of piss, to Kibaki’s sweltering sewage. Kibaki had succeeded in sending James scampering with nothing except the clothes on his back, and hope, to start a new life in Siaya. James’ neighbors would be trapped in Internal Displacement Persons’ camps for years. Almost forgotten. Others would die slowly for lack of care and access to basic resources. Over a decade later, no one has apologized for post-election violence. No one has been held accountable. Selected members of a community have been compensated. Others have been left to forage on their own. To these politicians, Kenyans full of hope are like objects of desire. Once they achieve a high, these objects are discarded in a state of neglect until when the next wave of desire kicks in. Tunaruka mkojo tunakanyaga mavi. Why even try? The answer is, hope. Kenyans are like James. Without hope, what else are we left with?

Failure

What is failure? Over the past decade, cases have been reported of students committing suicide after failing their national examinations, Kenya Certificate of Primary or Secondary Education. While there could be other underlying issues leading to these unfortunate events, scoring low marks has been reported as one of the reasons for these sad deaths. But think about it, in ancient kingdoms, military leaders would choose suicide by falling on their swords over the indignity of living with failure in war. Honour was of a higher calling to them, than life without it. In this sense, self-preservation meant an act of absolute excellence beyond reproach. The only people who come close to exhibiting this level of honour in Kenya, are the students who have taken their lives after going through what they consider unacceptable failure in exams.

While I do not advocate for suicide, wouldn’t it be great to see members of parliament, governors, the judiciary and Kenya police amongst others anguish over their failures? Wouldn’t it be inspiring to see someone resign in tears when patients are dying because there is an impasse over doctors’ salaries? Wouldn’t it be refreshing to see the head of criminal investigations resign when they cannot solve the gruesome murder of Chris Msando, one month before a hotly contested election? Not really. This is because failure is a profitable enterprise for most leaders in the Kenyan government.

Unlike these children who find the pain of failure of one examination unbearable, Kenyan leaders have a way of extracting profits from failure. To them, failure in the sugar industry is way to make quick money through sugar importation. Failing rains is a means to get tenders to import low quality maize and make quick profits. Every failure promises an opportunity for reward, consequences to struggling Kenyans notwithstanding. This is why there is no desire for excellence. Simply put, excellence and efficient use of public funds does not pay for most leaders. Can we listen to these kids? The younger generation is seeing something that leaders cannot see.

Bandaged

On the night of July 24, 2016 one Stephen Ngila Nthenge chopped off the arms of Ms. Jackeline Mwende. Ms. Mwende had been married to Stephen for a number of years before this incident. I learned about this case with shock. The utter brutality. The premeditated thoughts by this man and his determination to execute them. Against many odds, Ms. Mwende survived with multiple deformities. Stephen is in jail somewhere going through the unpredictable motions of what is Kenya’s judicial system.

I remember the outpouring sympathy to Mwende. I also remember calls to justice against Stephen. The calls were loud because of fear that Stephen like many others, would defeat justice. Only if he was rich. Or knew someone. The wheels of Kenyan justice need a lot of social media activism before they can turn. And Twitter was up in arms to ensure Mwende received justice. Anyway, what caught my attention to this case was how quickly NGOs, always hungry for visibility, descended to Mwende’s house. Big vehicles with cameramen were tweeting photos of themselves passing packets of unga to Mwende. Salt. Sugar. There were multiple offers for prosthetics. Anything to help.

The story of Mwende has stuck with me for various reasons. One main reason is because I see her case as symbolic to what Kenya has become. A state assaulted through premeditated violence, chopped to disability and bandaged now, mostly by NGOs, to enable some level of basic existence. And this assault occurs every five years when elections are conducted. Then follows a period of patching. And hope that things would get better. Like James hoped in Siaya.

When did this assault start? And what abated it to these tragic levels? Like Kenya, Mwende had been neglected by people charged with protecting her. Be it family, or people in authority like the police, or neighbors who would always hear her screams every night and ignore them. In this jungle of Kenya, you have to have a thick skin to survive. And of course, hope. The system had failed Mwende and left her at the mercy of a sadistic maniac who was her husband. And Stephen being a good criminal, had sensed this failure in the system and taken full advantage of it. This is Kenya. Abandoned by people charged with protecting her, abused progressively, chopped, bludgeoned, before finally, for adventure, getting limbs amputated. Kenya being unable to take care of herself, is being propped by NGO’s who take multiple photos of her, caricatured in multiple forms, to justify their existence. The only difference is that the people who have assaulted Kenya, unlike Stephen, are free to assault again. And they are being cheered wildly by their cronies with tag lines like “Kieleweke” and “Tangatanga”.