Sometime in 2010, I had the idea of writing a poem to explore the trips that my family made several times a year back to our rural home, when I was a child. This desire gave birth to the long narrative poem called “We Leave Our House to Go Home”, which resonated with audiences in Kenya and beyond. Yet the poem is deeply personal and reveals a journey of transformation and becoming, beginning with my family’s move from our rural home to Nairobi, Kenya’s capital city, and my emergence as a city girl. The city girl lives a two-edged status of inevitable alienation from original roots on one hand; and on the other the pioneering opportunist creating a new way of living in a new country. As a consequence my life at times feels like a rapid fire pendulum, quivering in one place, then another, and not making much progress in either direction. But let’s start at the beginning.

According to my parents the late William Ndala Wamalwa and Rose Nanjala (nee Uluma) Wamalwa, in April 1963, my family relocated to Nairobi from Namirama in Kakamega, western Kenya. I was five years old. Four years later, my father announced quite brusquely, with no preamble at all; because-of-course-we-children-should-just-know; that we were going back to our “real home”, back to Namirama. I was then nine years old. Although only a scant four years had elapsed since our leaving, new experiences from the world I now inhabited in Nairobi, had so profoundly reengineered me, my memory of this “real home” had all but disappeared. For me, Namirama was like one of those relatives who comes to you, expecting you to instantly jump into her arms because she developed a strong bond with you, when she saved your life and nursed you back to health after a terrible accident when you were three; and to her horror you don’t recognise her.

That first trip etched itself on my mind, as a consequence of the unbelievable levels of discomfort the family suffered on the road trip home. But this was just the beginning. Over the years we made many trips to this perplexing place I learnt to call home, all reliably uncomfortable. It’s perhaps not surprising I married someone whose “real home” was only two hours away from Nairobi, or that I wrote a long narrative poem about those horrifying experiences. It’s not astonishing it took many years for me to see the beauty of “home”, this green equatorial paradise with rolling hills, rivers and streams, amazing bird life, perpetual rain, the Kakamega Forest, and my relatives.

When I wrote the poem, I thought the experiences of the road trip home were confined to me, and my family, until I shared it. The poem’s first public outing was a reading to a young woman who had grown up in South Africa, but came originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo. I read and read then I stopped, embarrassed that I was boring her with the never-ending words. I looked up ready with my apology only to find rapt attention. No please, don’t stop, she said.

In 2014, I crafted a show of dramatized poetry called “Silence is a Woman” and placed this going-home poem at the end of the production. After one performance, a woman came up to me and whispered, “What about the trees, you can’t leave out the trees!” I was delighted, I knew exactly what she was talking about. Yes, the trees! But I was so surprised, how did she know about the trees? I thought that was just my experience. You see, when I was a child of three, my mother took me, my sister and my baby brother to Kilifi District, on the Kenyan coast, by train, to join my father who had just graduated from Makerere University in Uganda and was now working as a colonial District Officer. As the train moved, I watched trees run, they chased our train, running beside us for a time and then speeding past us, showing off their love for speed. At the end of our journey we found them gathered in a huge welcoming forest at our destination.

Had other people seen the world, this way? It never occurred to me that this was a typical childhood experience – the sight of trees moving past you, and almost with you, as you sit in a car, bus or train. We humans live life in self-contained silos, separate and alone, yet so much of our experiences are exactly the same. So here is the verse crafted from that experience with the trees.

“Trees chase after our car, as we speed home,

Eucalyptus lope with wide steps,

Tall yellow Acacia’s flash past us, in wild chattering gangs,

Ponderous flame trees, dressed in bright orange, plod along, waving their heads from side to side.

The trees are sneaky, when we stop; they stop too,

As soon as we move, they start running again,

They race us and win.

We arrive, and find ourselves in a land of many trees.”

I have since found that although “We Leave Our House to Go Home” is many-layered, it is first a story about the dissonance and dislocation. It is about arriving at your new location and looking quizzically at the place you used to call home, which in turn looks at you and wonders how strange you have become.

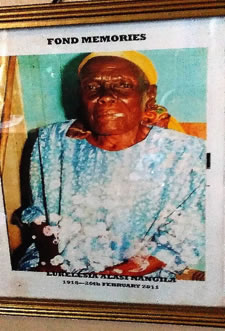

An example. After I reached adulthood and my grandmothers and aunties started to die, I created my own tradition of taking with me their old water pots and other vessels after their funerals. It started with Kukhu Jedida Khasandi my mother’s mother who died in 1995 at the age of 75 years. After her funeral I bequeathed to myself her old wooden milking vessel which was about to be thrown away. When Senge Lukalesia Alasi Nangila, my dad’s eldest sister and the eldest daughter of their father, died at 93 years in 2010, I took her old clay water pot. Along with my grandmother’s wooden milking vessel, I now have four clay water pots, which keep me company and remind me of these beloved relatives.

Senge Lukelesia Alasi Nangila with a cigarette in her mouth. Senge Lukalesia helped inoculate me against the toxic masculinity found in the city with the dictates that limited a woman’s life. She showed me that a woman can do anything she wants, and still smoke, drink whisky and still be loved.

But meanwhile I have earned a reputation as that weird Nairobi relative who likes useless old things. My relatives laughed at me and treated me like an eccentric cute poodle, but are now no longer surprised when I ask for a pot. The latest water pot belonged to my Senge Nasambu Akeso who passed away in April 2017 at 95 years. This one is large with a broken mouth. Apparently, I missed the good one by a week when it broke just before her death.

The poem “We Leave Our House to Go Home” is also about how the world occurs to a child versus how it occurs to an adult. The road home from Nairobi starts with a relatively safe section from, Kangemi, to Limuru. At Mai Mahiu the road becomes the “dreaded” or “scenic” escarpment road, (depending on whether you are a child or adult,) as it begins its ascent to Mount Longonot before it starts its descent down to Naivasha town.

Every time we approached the Mai Mahiu section, my emotions churned as my stomach tied itself in knots and I intermittently closed my eyes trying to shut out the many sources of danger that I could see looming around me. The so-called escarpment road was a thin and winding ribbon, perched on top of a cliff on the Great Rift Valley, which had fractured the country many eons ago.

As we drove, the grown-ups ooohed and aaahed at what they claimed were panoramic views of valleys, savannahs, lakes, rivers and mountains spreading all around us. But all I could see was danger. On the right, signs warning of the possibility of falling rocks were written in bold panicked capital letters. “BEWARE OF FALLING ROCKS”. But those weren’t even rocks, most of them were huge boulders imbedded into the side of the steep cliff-side. Just one could smash our car into smithereens. And then there we were, stuck behind a long line of lorries, petrol tankers and buses for miles at a time; crawling at 20 kilometres an hour, making us even easier targets for those falling rocks. What were the warnings for? What exactly were we expected to do if one of those boulders dislodged itself and started to roll down towards our car? Really, who had selected this place to build a road?

Throughout the escarpment phase of our journey, I played a game in which we would only be safe if I did not look down into the wide steep valley. But even this game did not keep visions of our small VW Beetle missing the next turn and flying off to plunge and scatter all eight occupants; five children, two parents and a cousin-maid, onto the waiting jagged rocks and boulders. Our car would not grow wings like the ones in cartoons and swoop back into the air at the last-minute, saving us from destruction.

After that first time, we went to our real home at least two to three times a year, to visit the strangers my parents called our up-country relatives. Real home? More like surreal trip home. And then the 1980’s arrived and brought potholes and deteriorating roads with them. The escarpment road was not spared and soon the valleys became strewn with the carcasses of vehicles that had missed their step. I remember the World Bank stating quite categorically that the 1980’s was a ‘lost decade for Africa’. The continent went backwards rapidly and for me the most visible evidence was in our cracked and deteriorating roads which made the family’s journey back home an even more terrifying prospect.

I wrote “We Leave Our House to Go Home”, in 2010. It came tumbling out of me effortlessly, and full of so many words I thought it would never stop. My plan had been to write the poem in two parts, with the second part, called “Home”. But that mysterious place from whence my poems come has refused to give up the goods; all my “part two” attempts have been stilted, contrived, self-conscious and just not as good as part one.

WE LEAVE OUR HOUSE TO GO HOME!

By Sitawa Namwalie

We start,

We are told we are going home.

What?

We are home.

Is this not home?

This place we live?

This is home!

I have climbed those trees,

Fallen and broken my hand in that ditch,

I have raced my brother and won on that wide green lawn,

I have hunted tadpoles in that pool over there,

You can’t see it now; it only fills up with water when it rains.

Is home not this?

No.

No?

My father hands me an un-embellished, ‘No’.

My mother gives me a flat ‘No’.

On this, they speak as one.

No.

No?

“This is just a house”, they reply,

“Not even ours!

It is owned by the government.”

Oh!

We leave our house to go home!

We pack our bags;

Clothes, shoes, Vaseline, toy cars, dolls, books, Monopoly, transistor radio.

We pack more bags;

Sugar, tea leaves, butter, oil, maize meal, cocoa, sausages, bacon; we can still afford these things.

And 8 long loaves of Kumanina bread!

Kumanina?

What a rude word.

Why is it called that?

Does anyone know?

No?

We leave our house to go home!

We get into my dad’s car,

A brand-new VW Beetle.

Five young children, a mum, a dad and a cousin-maid.

We take turns sitting on each other,

Except Dad of course,

He must drive.

We leave our house to go home!

Limuru!

We children speak up hopefully,

“Are we there yet?”

My father laughs indulgently,

“Hahahaha!”

“No.”

There’s that un-embellished ‘No’ again!

“Not yet,” he says, his eyes twinkle at me through the rare view mirror,

I’m perplexed.

We have never gone this far in our fun-filled-after-Church-Sunday-drives.

It can’t be much further!

It will be over soon!

Where are we going?

We leave our house to go home.

Kinangop!

30 more kilometres, hope returns.

It bounds back, panting, joyful like a puppy.

“Are we there yet? Are we there yet? Are we there yet? Are we there yet?”

“There I can see it, there!”

“It’s there over that hill. There!”

“No!”

No?

Mum’s says, “Stop disturbing your father, let him drive.”

Her voice is sharp.

There is no joke in it anymore.

No.

None.

I exhale all my hope.

How far do we have to go to get home?

We leave our house to go home!

We start a steep climb on a narrow road.

Sheer cliffs rise on one side and fall on the other.

Up, up, up we go, through savannah, alpine forest, dry scrub land, wooded dry-lands, white highlands;

Then down, down, down to an equatorial green land that belongs somewhere else.

Not in this dry country Kenya.

We leave our house to go home

Trees chase after our car, as we speed home,

Eucalyptus lope with wide steps,

Tall yellow Acacia’s flash past us, in wild chattering gangs,

Ponderous flame trees, dressed in bright orange, plod along, waving their heads from side to side.

The trees are sneaky, when we stop; they stop too,

As soon as we move, they start running again,

They race us and win.

We arrive and find ourselves in a land of many trees.

We leave our house to go home!

Don’t think I saw the wonder of the changing landscape,

The backdrop movie, shifting, around us,

Leaving, arriving.

I saw none of it.

No.

My mind echoes city lights.

Nairobi is my jewel.

I ask my father,

“Is there light at home?”

“No!”

No?

My father laughs again, this time amused,

“Hahahaha!”

His eyes touch mine in the rear-view mirror.

“Electricity does not stretch so far,” he says.

No.

He is, matter-of-fact, “There is no light at home.”

No?

No? My mind reels.

No disco-dancing neon light?

No hanging out at Carnivore on a hot night out?

No chilling with a hoard of hungry girls at night?

No!

No light to bathe me, wash me clean?

There is no light at home?

We leave our house to go home!

Eldoret.

Punctures come thick as rain!

The first is a joyous affair.

We all believe it won’t happen again.

By the third puncture, we all know how to change a tyre, even my kid brother.

First, push the car off the side of the road, onto the verge;

Second, find stones!

To prevent the car from rolling away!

Third, put broken tree branches on the road!

To warn other motorists!

Step four, fix the puncture.

By the 4th and 5th puncture, I am worried,

Home speaks in code.

Maybe home is sending a message in its own crude way.

It does not want us to return.

Home speaks secret words buried in repetition.

It sends a celestial whisper,

No! Do not return. No! Do not return.

There is nothing left for you here! No!

We leave our house to go home!

Kisii,

Kapsabet,

Kisumu,

Kakamega.

The tarmac road turns to dust,

The car starts to bump, list, sigh, it slows down in protest.

There are no roads here, no.

Just tracks made by cattle, barely visible in the bush.

We reach a river; with a bridge made of old wooden planks and colonial memories.

This river is not a memory.

An empty long gorge, with wide banks, a bed of rocks and boulders, with the name ‘River Something’ on a sign post.

This is the real thing,

The River Nzoia.

Yes!

We leave-our house-to go home.

Mumias,

Sivilie,

Chebuyusi,

Navakholo,

Nambacha,

Namirama.

We arrive.

Grandmother ululates; a loud long, piercing sound,

She holds her hands outstretched,

Her body rigid in a rictus of astonishment.

She leads a crowd of women, children, men;

They embrace us,

A tangle of humanity, noise, movement, singing, dancing;

Tears of joy lifted in celebration!

Grandmother stops her singing delight to ask,

“How is Kenya? How is Kenyatta, your president?”

I understand.

She and I come from different countries,

She doesn’t speak English, we don’t share a president; no wonder she looks foreign.

We leave our house to go home.

We stand still as Grandmother prays her foreign prayer,

Filled with images of Jews, wandering about for 40 years in deserts,

Crossing the Red Sea, which parts unexpectedly, to create a path.

It is only God who can manage such miracles. Baba!

Like the Israelites in Egypt escaping Pharaoh and returning to the Promised Land,

He has come back, and not empty handed. Baba!

He has prospered, Baba!

Returned. Baba, Jehova Jire!

After 10 years of wandering in the dangerous city lights,

Where men have no souls. Baba!

Where people can disappear without trace, as if consumed by wild beasts. Baba!

He has come back with children,

(Most of whom I have never seen.)

We thank you, Baba.

We thank you, Baba.

Baba! We thank you.

For you have been with him, Baba!

You have smiled on him, Baba!

He comes home with children; a car,

With a car, Baba!

Oh, that my son can find the riches to buy a car…

Like the son of Manyonge,

Like the son of Makokha,

Like the son of Siganga, like my son!

And on and on and on, her prayer, sings, and shouts, hums and flows, rises and falls and…

Riswa! PAP!

She ends the prayer with a loud abrupt sound.

I am startled. And wiser.

I learnt a lot from that prayer.

We are Jews from Israel!

We leave our house to go home.