I was once suspended for inciting a strike. Or at least that is what the letter said. It was the March of my second year in high school; in my first, we had gone on strike twice. The first was a peaceful act of protest that begun at the assembly ground on a cold Monday morning, moved to a kamukunji in the sports field, and ended with us walking seven kilometers to the highway.

The second was a brutal affair. To this day, I am not sure exactly why we went on strike. Days before the national exam begun, we woke up in a war zone. People breaking window panes, banging on doors, and fighting. What we woke up to, in the rooms nearest the toilets, which were nicknamed Soweto, was a hooded boy whipping one of my roommates with a hockey stick. The combined chaos was traumatic, and explains why I still hyperventilate whenever I hear a metal door banging.

The reasons for both were varied; the first involved a long list of asks, including a new TV. The reasons for the second were less defined, and did not matter much as we ran through the trees and climbed over the gate at midnight. What did was saving our lives, and helping the injured away from the mess.

After the chaos of my first year, we got a new deputy principal, a disciplinarian tyrant who came with the energy of a man on a mission. With no rules beyond those he decreed. Those rules were madness, and his favored way of implementing them was slaps, punches, suspensions and expulsions.

While I sat on the floor in his office that Wednesday morning in March, he said “I didn’t even know you, so huwezi sema ninakukuonea.” He said other things, but that is the sentence that lingers to this day. On that cold floor with my friend and classmate Jackson, who had returned from a previous suspension just two days before, our attempt at explaining what the grievance was dug us deeper into the hole. It was a simple demand, to restore the labor system we had found, which made first years the “wheelbarrows” of the school, with duties reducing as one moved through the four years. We had paid our dues, we felt, but the man sitting across from us did not want to hear. “You were planning a strike”, he repeatedly said, and our attempt at protest was indiscipline. We returned two weeks later, to sit outside the principal’s office as the adults in the room discussed how we should be punished. I was called in, for a short five minutes. I stood at the end of a long table, in a room full of men (including my father), and answered three questions. None was about what the issue had been, or what I had hoped to achieve. At the end of it, my tormentor pushed a ‘contract’ that stated that if I was caught in any act of indiscipline again, I would be expelled. Then I went back outside and sat. An hour or so later, my father, a retired high school teacher at that point, walked out right past me.

I spent the next three nights digging a pit, my act of penance. In my file, the contract sat at the very top, a reminder that this one misunderstanding would be part of my school record forever. Jackson did not survive. He survived our suspension, but he was on a third one within a week for a frivolous charge. Then he was expelled.

The result of this tyranny, which included a spy network (which is how they had learnt of our plan to approach the man), was not a better learning environment where discipline thrived to everyone’s benefit. It was the reverse. We became a police state in many ways, engaging in guerrilla acts of protest and subterfuge that extended beyond the school fence. Once, someone poked holes into the deputy principal’s tyres while his car was parked outside a hotel in a nearby town. Then, someone punched his young son in the face in the middle of a sports day. The culprit was never caught, even though the incident took place in the middle of the day on a field with hundreds of people.

Burned spies were hunted down and, in the middle of night, beaten to a pulp by groups of people with anything they could get their hands on. They lost their mattresses and blankets, and had to sit watching their laundry dry because it would disappear if they blinked too slowly. They became social pariahs, often only saved by being appointed to the prefect body, if they were not already members of it. Still, the resistance was broken by the brutality of the consequences.

The only time we came close to striking again was once when the deputy principal horsewhipped someone so badly he tore his back in multiple places. But there were many foiled attempts, sometimes only known to us when people were expelled. The relationship between the administration and the student body was irreparably broken, and it felt as if we were hostages as opposed to teenagers seeking an education. There was no recourse for injustice because even the parent body felt such measures were necessary to keep the peace. But it was not peace, it was just the absence of war.

Once, in my third year I think, we came back from the holidays to new rules. Only school uniform would be allowed within the school walls., Anything else we had with us was left in a pile, stashed in sacks, and hidden in the stores. Our t-shirts, jumpers, and pyjamas stayed there for more than six months. In the meantime, in the freezing days of Kijabe, we suffered recurrent bouts of flu and chest infections. Any attempts at getting our clothes back, so we could keep warm, resulted in the same consequences as organizing a strike or burning a dorm. So we stayed submissive, until we eventually could not. Three friends and I cornered the deputy principal one Saturday afternoon as he was walking up to his office. We told him, as politely and as vaguely as we could, that we were barely surviving the cold nights. He had this odd smile on his face, perhaps because of the distance we kept from him while we relayed the plea. Not be within arm’s reach of the man was a survival tactic, because he was ambidextrous with his slaps. He listened, and said repeatedly that whatever was not part of the school uniform was contraband. We told him about the chest infections, and the flu, but he was adamant. So we thanked him for his time and bid him a good day. It was only three months later that we got our clothes back, mouldy and damp. We could now wear them as long as they were under the school uniform. It was a small win, but a win nonetheless.

The man himself became my unwilling mentor (the lack of will was on my part) as I became the school pen. He pushed me to write more, and would publicly embarrass me if I had nothing for my five-minute news bulletin time slot during the school assembly. My reports were a mix of journalism, satire and sometimes pure gossip, a break in an otherwise boring school tradition. My personal relationship with him evolved from that Wednesday morning in March to somewhat of a distant friendship. He was still a brutal, angry man, but for some odd reason he thawed around me. To the point of once reminding him of a time he slapped me so hard I farted as I fell on my back in his office. He laughed about it, we both did. But his idea of our inclination towards mischief remained, as did his spy network and his own creepy appearance in the school at odd hours, hunting for new culprits.

Our school grades remained unchanged, but for the next three years, there were no successful strikes. Any problems we had that we couldn’t solve ourselves, we swept under the rug and moved on. Any knowledge we had of who was sneaking out to meet girls or buy food or go drinking we kept to ourselves. Unless it somehow found itself in the wrong circles, then all we saw was people carrying their metal boxes and threadbare mattresses out of the gate. Or coming back with a roll of wire mesh as punishment, before being expelled.

***

Since the first school strike in Kenya, at Maseno School in 1908, students have gone on strike for almost any reason you can think of. At Maseno, the problem was that no learning was happening. The students were instead manual laborers, until they got tired of it.

Once, Alliance High School went on strike because there had been a fight, about foreskin politics, during a football match. Then some strikes, and I would say quite a sizeable number, have been spontaneous, because as Margaret Gatimu found out in this study, of “established cultural norms which dictated fights for power and status.”

Then of course there have been more legitimate causes for protest. Trying to get the attention of the administrators and sometimes even parents to a real or perceived injustice. Or even, as we’ve seen lately, real criminal activity by and against students. In other places it has been teachers driving strikes, to make the institutions ungovernable and get rid of administrators they don’t like.

There were schools like Njoro Boys in Nakuru County and Githiga High School in Kiambu county which were legends in the strike business. I think I once heard they were gazetted at some point as problem schools, got two deputy principals, and gave one an open ticket to instil discipline.

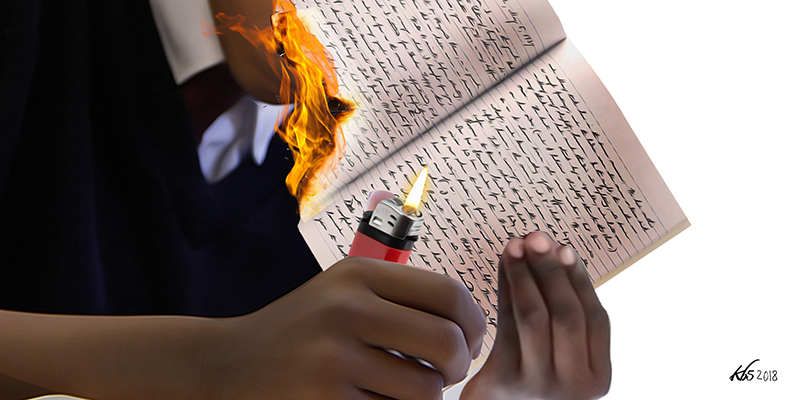

In other schools, there were cases of rapes and deaths and fires. There was Bombolulu, St. Kizito and Kyanguli. There were claims of devil worship and homosexuality. The system doubled down on punishment to find some order, built on the colonial thinking that power is always right. And that children are always wrong, and any stubbornness on their part was an act of defiance. It was a system built to subdue; a boot camp designed to break young men and women and teach them their distance from power. To silence their ability to express themselves, their needs, and their problems. To teach them that to survive, they had to keep their heads down, their mouths shut, and their sexuality suppressed. Granted, the same thing was happening in the larger, adult world outside as well. So they expected their kids to submit too.

For the first seven years after independence, acts of protest in high schools were often peaceful. Then something snapped in the 1970s and they became more violent, more coordinated, and more destructive. A new authoritarian trend was trickling down the Kenyan social structure again, and the subjects in that system were reacting. It made high school and university students experts in guerrilla warfare not just against their teachers, but also against the state and its security forces. It brought fire, for example, the fore as a tool of choice because it is fast, vicious, and requires less cooperation on the arsonist’s part. It made administrators and teachers enemies of the majority, and anyone working with them equally so. It made betrayal punishable by beatings and recently, even poisoning. This is the stuff of war, not education.

Between 1986 and 1991, according to BA Ogot in his memoirs My Footprints on the Sands of Time, there were 567 school strikes (305 mixed schools, 206 boy schools and 56 girl schools). That was a rate of a school strike every two days of the school calendar. Despite this, President Moi only appointed a commission of inquiry after The Rape of St. Kizito where 71 girls were raped by the male students and 19 died trying to escape from their attackers.

That dark night was the worst yet, and it had begun as a protest against fees. The girls refused to participate in a planned strike, and on the night of July 13th 1991, all hell broke loose. The 271 teenage schoolgirls fled and hid in their biggest dormitory, locking all points of entry. At 1:00 a.m, after an initial attempt to break the doors had failed, the boys came back with bigger stones and smashed the doors down. The result was a massacre that shocked a nation, and the immediate consequence was the arrests of more than ten suspected rapists and three watchmen.

But the reaction, or rather the response of the school’s administration was the most telling of the problems emblematic of our school system. The principal said the school was haunted, and then added that rape was, in fact, a common occurrence there. He seemed to be saying that the only difference of the night of July 13th was that 19 girls had died, four of them from suffocation. The boys, as his deputy infamously and tellingly told the president “…just wanted to rape.”

It was appalling, but the response was not to try and make schools safer by listening and responding to student grievances, it was to double down on disciplinary measures. The Rape of St. Kizito was not the only time that year that boys in a mixed school broke down doors and dragged girls outside where they repeatedly gang-raped them. In another major incident of the year in another school, students protesting the bad state of their food drowned the school cook in a vat of porridge. The only reason St. Kizito made news, as someone noted at the time, was because 19 girls died. This remained the case when, 7 years later, 25 girls died in Bombolulu in a school fire.

And three years after that when 68 young boys were turned into smouldering piles of ash at Kyanguli. It was one of those days when everything that could go wrong, goes wrong. Arsonists begun a fire in a dormitory, then it got out of hand because someone had lost the key to one door and no one bothered to change the lock. Half the boys in bed that night couldn’t make it to the other side of the fire, and in the mix of panic, stampede and survival instinct, died. The same sequence of events happened at Bombolulu, except for the part where the girls were actually locked in their dorms at night. Sources differ on whether it was arson or the result of an electrical fault.

Then, in 1999, a group of arsonists locked four of their prefects in their cubicle at Nyeri High School, and doused it with petrol before setting it on fire.

In all these cases of extreme violence, there was always an underlying reason. At Kyanguli it was the cancellation of the results of the previous years national exams for 100 students, and the discussion, or lack of, on whether they should pay school fees to resit the exam. The pattern was the same. The administration had refused to listen to the students, and had responded only when it was too late. In their own macabre way, these extreme cases forced not just the administration, but the entire educational system to listen. But it was only as an immediate reaction to the tragedies, after which the system slid back into its old ways. And each generation of teenagers found that the only way to get the system to respond was to protest, burn a dorm, beat teachers and refuse to stay in school. Because of the overwhelmingly male nature of such violence, many of the strikes were in boy schools. Girls had to, and still have to, contend with the added gendered risks if they wanted to burn their school and escape in the middle of the night.

Each wave of school strikes is explained away with rampant indiscipline and the lack of corporal punishment in the school system. Despite the fact that research shows that violence among teenagers can spread like a contagion, as it often does in Kenya schools every few years, the glaring risk factor of one-way communication remains unchallenged. Children are meant to be seen and not heard and even teenagers, who are just years or months away from adulthood, are still considered treated as kids. Because often their priorities are different and immediate, like better food or less bullying, they are postponed until they cannot- be. Now, kids caught up in the only recourse they feel they have, are to be condemned with a criminal record for the rest of their lives.

The same approach to strikes in universities that has cowed student bodies and made those education institutions prison-like entities will be escalated at the high school level on minors. If you think about it, the school system and the prison system have many things in common… The authoritarian structures, the set dress code, the emphasis on silence and order, the negative reinforcement, the loss of individual autonomy and the collective punishment. Like a prison, students walk in lines and have set times, enforced with severe punishment, for eating, recreation, and sleep…and recently, just like in the prison system, we are trying to set the same uniform for all schools in the country.

The state is doubling down on punishment despite the fact that our laws, despite their many flaws, are insistent on the protection and privacy of minors, even when they exhibit criminal behavior. But none of this will help, at least not in the way they think it will. If the issues that trigger strikes remain, and the adults in the room insist on speaking above the kids they have been tasked to educate, then nothing will change.

Every generation is expected to have a sense of history, but high school students are still adults in the making. Which is why we place them in the care of fully-formed adults who, we expect in theory at least, have a sense of history embedded in their moral and professional code. But if the havoc of school strikes hasn’t changed much in the last 40 years, and students only stay in schools for four years, then who isn’t learning from experience?

***

A few years after I left, I was in my alma mater for an event when I bumped into my former tormentor and mentor, and we took a short walk together. There were many things to talk about, including how someone had burnt a dorm the previous term. The forlorn look on the man’s face, of failure on his part, was matched with his pursing lips, like a quiet determination not to let it happen again. I did not pry and got the details from someone else. After years of foiled strikes over different issues, both flimsy and salient, someone had finally succeeded. His choice of weapon, fire, was combined with another trait that tends to emerge in war zones; he was a lone ranger. He torched one of the biggest dorms in school, not at night, but in the morning while everyone was gathered for the school assembly. All the teachers saw was the smoke billowing towards the sky. There was no way to know who the lone arsonist was because the student body went on a stampede, expectedly.

A few years ago, the man who represented law and order at my alma mater tragically lost his son. The boy who had been punched in the school field, now a young man, drowned in a swimming pool. From the reactions in the many alumni Whatsapp and Facebook groups, what stood out was the lack of sympathy for his father. More than a decade after some of us left the school, which he had also left by then, he was still considered a vile human being who deserved any misfortune that came his way. This being said by people who were young parents, and who in a few years, would be driving their kids to begin their new high school life.

High school students might still be minors, but they are not the mindless creatures the school system is designed to treat them as. And they keep reminding the adults in power about this, generation after generation, often fruitlessly. The adults imagine schools to be utopias. They are not.