December 27, 2002. 10 in the morning. Donholm Primary School. Embakasi Constituency. I am in line to cast my vote in the most important election in the country’s history up to that time. It is also my second election having voted for the first time in the 1997 election for the dynamic Charity Ngilu and her Social Democratic Party (SDP), who lost to Moi. Now in 2002, as I stood quietly in line and thought about the election I was to take part in, I was quietly confident since my favourite politician had banded with many others to form a coalition against Daniel Arap Moi’s preferred candidate, Uhuru Kenyatta. As the line got closer to the school gate, I noticed that there were posters on the floor with the message Uhuru Ni Moi. These posters had images of both the outgoing president and the presidential candidate and the jogoo that represented the political party that had been baba na mama to me for all my life. The message was simple enough. Voting for the new party leader was the same as voting for the outgoing leader.

The Moi leadership was real to me. As a child born in the 1970s and growing up in the 1980s, I would observe the leadership of this man from Sacho keenly. As a child, I was the biggest fan of Baba wa Taifa, Mkulima Number One, Everything Number One. The image of the tall, lanky man getting into the dirt to help build gabions with fellow Kenyans on VOK (now KBC) was seared in my memory. Favourably. I was one of the many children singing praise songs of the dear leader as a member of the Nairobi Primary Schools Mass Choir at the Nyayo National Stadium on national holidays.

I grew up seeing the President taking part in events every day on the television, but my life was also touched by him and the projects of his administration. My personal favourite was the free milk that would come to school every Tuesday that we knew as Nyayo Milk. The orange packs with diagonal white stripes held delicious milk. And it was free. Then there were other projects that made me proud to be a child of the land of Kenya. The All Africa Games in 1987 which brought the continent to Kenya and Michael Jackson’s brother Jermaine to perform at the opening ceremony. The Nyayo Pioneer – my country had built its own car. While the car, driven by the president at Nyayo Stadium, didn’t run for long, we could brag that we had our own car as a country like Japan had Toyotas, France had Citroen, the UK had Land Rover and the USA had Ford. In my young eyes, my country was perfect.

Goldenberg would introduce the country to the concept of “billions”.

The first time that I realised that things weren’t as rosy as they seemed in my mind was in February, 1990. I had just started my form one classes at Upper Hill School and I was headed to get public transport in town when I found drama on the streets as riot police chased citizens around town. The cause of the riots was the slain body of the then missing Foreign Minister, Robert Ouko, had been found and people were unhappy. The well-spoken, polished minister had been my favourite in the cabinet of my still beloved Nyayo. As the weeks and months went on, my carefully constructed view of the leader of the country started unravelling as more people spoke out in protest against his administration. The scales were falling from my eyes.

Not long after, we would hear of a term -Goldenberg- which put to shame all previous scandals that had been creeping into the Kenyan consciousness. Goldenberg would introduce the country to the concept of “billions”. Before then we would speak of things in hundreds, thousands, millions and hundreds of millions. This madness saw our currency devalued by one third overnight leading to hyperinflation that was never seen before nor since. The economy would almost grind to a halt and would only really recover after the dear leader had left office in 2002.

The human cost of the presidency was also steep. Kenyans would die mysteriously in Molo, Burnt Forest and other areas to subvert the elections of the 1992. With a little over 30 percent win, Daniel Arap Moi was announced President by Zacchaeus Chesoni, who was then rewarded with the Chief Justice position. Other Kenyans died in Likoni and Rift Valley in 1997, leading to the incumbent remaining in office as Samuel Kivuitu announced his “second term.” When people weren’t dying because of elections, many who had been critical of the dear leader would die in mysterious circumstances. By car accident. Shot. Others would appear broken after being tortured by state operatives. Those who weren’t dying were fleeing the country like rats off a sinking ship.

By 2002, when I was casting my vote, the country was so broken that everyone had to gang up and vote off the administration from the Survivor Island that Kenya had become. I joined my country and voted for the opposition. The tribe had spoken. We expected freedom like never before. We would have three years of plenty democracy, two years of bananas and oranges and five years of what appeared to be an uncomfortable unity government under Mwai Kibaki.

Another election was in the offing. This was again the most important election in my lifetime. It’s funny how every election is the most important election in our lifetime.

August 8, 2017. 4pm. Highway Secondary School. Starehe Constituency. Another election was in the offing. This was again the most important election in my lifetime. It’s funny how every election is the most important election in our lifetime. As I walked towards the secondary school gate, I would see some other discarded election posters as I had at previous plebiscites. Most were from activist Boniface Mwangi, who was running for area MP. While we were chatting, the security guard at the voting station gate left me to let in a truck filled with army personnel. At the sight of that many soldiers in the sleepy South B suburb, my blood went cold as I walked in to make my mark on the ballot in this latest “most important election.”

It was a half hour affair as I walked into the polling station, got my voting papers and made my decision in the booth. Choosing not to waste my vote, there were only two possibly candidates for me for the Presidential ballot: incumbent Uhuru Kenyatta and opposition leader Raila Odinga. Between the two, mine was a simple choice. It was either to stick with the incumbent who had a record over the last few years or go with a new man who was as yet untested where executive powers were concerned.

The incumbent, Uhuru Kenyatta, had come to power facing charges at the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity for his actions during previous elections. The same applied to his running mate, William Ruto. It looked bleak for him but against the odds, he won the election, took over the State House and started pretty well. He promised free laptops for all Standard One pupils in government schools. Businesses even tendered for this project. In the end, this signature project went nowhere because of irregularities in the tendering process.

He promised a new era of leadership but what we got instead was mega corruption exposes. Arap Moi’s modus operandi had been crushing the economy with scandals like Goldenberg and bankrupting every government agency and parastatal. This new guy’s specialty was nothing short of magic. Billion dollar loans called Eurobonds disappeared mysteriously and those connected with some of his cabinet members carted off money in sacks. Then there were family members at the centre of many of the administration’s scandals that were faithfully exposed by the opposition. The worst part was that the amounts involved were gargantuan compared to his political godfather who had been running the country down for close to quarter of a century. On grand corruption, the student had outdone the master.

On grand corruption, the student had outdone the master.

The human cost of his administration hadn’t been the best either. Many people who had been witnesses to the cases at the International Criminal Court had disappeared. People who had views that differed from the country’s leadership with names like Abubakar Shariff, an imam known as Makaburi, and Sheikh Aboud Rogo, were gunned down in broad daylight. In just under 5 years, the student had learnt to use violence with the same vim as the teacher.

It was, as mentioned before, as simple a decision as I had made in 2002 when I ticked the presidential ballot and left to follow the proceedings from my house.

Friday, September 1. 11:00am. The Supreme Court was ruling on an election petition by Raila Odinga claiming that the election, which had seen Uhuru Kenyatta declared the President-Elect, had been a farce. The whole country was on tenterhooks as we waited to hear the ruling. It had been a tense few days since the final hearing of the Presidential petition in Kenya. A couple of weeks since we went to the polls with nearly thirty people killed by the state’s security machinery in that time. Chief Justice David Maraga read his ruling: the election was nullified and the country would be going to another Presidential election.

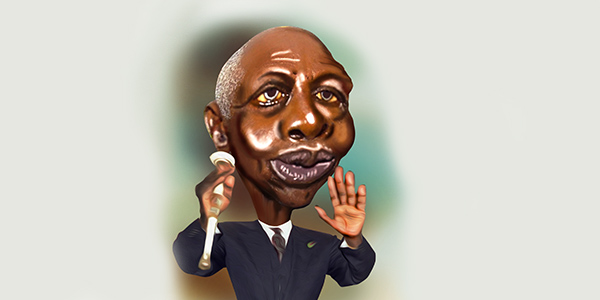

A few hours later, we would see the President, red-eyed and furious, accepting the justice of the court but undermining the court with his statements. As this voter saw him trembling from anger and possibly other substances, he remembered that poster he saw on December 27, 2002. It was right after all.

Uhuru ni Moi. Only worse.

By James Murua