In the space of two months, Kenya has lost two of the better-known pioneering newspapermen in post-independent Kenya: Philip Ochieng and Hilary Ng’weno. They were contemporaries who died within weeks of each other aged 83. Both were archetypal print journalists – with a distinctive editorial style and intelligent and passionate about how they presented the news.

Both had a flair for the English language, both were pro-establishment journalists and both largely made their imprimatur during the one-party state of Daniel arap Moi. Both were stylish in their attires: one favoured Saville Row-type suits, the other preferred free-style dressing, almost informal, and spotted a scraggly beard that grew white with the years.

As talented print journalists, both were naturally inclined to the literary word – one even penned fiction, the other wrote a journalistic treatise, examining and locating the pitfalls of the Kenyan media scene in a specified time-span. Both cherished their private spaces and both could have been described as loners.

Hilary Ng’weno came back to Kenya from studies in the US at an exciting time in Africa. More than 15 countries attained their independence in 1960 alone. In East Africa, Tanzania and Uganda became independent in 1961 and 1962 respectively, to be followed by Kenya in 1963. Pan-Africanism. A little utopia. Five-year development plans were ambitiously written. With the newly independent African states bubbling with enthusiasm, nationalism and optimism the 1960s were an interesting time to be in Africa

In Kenya, Paa ya Paa (The Antelope Rising), the oldest Pan-Africanist Arts Centre, was established just after independence in 1965. In the many years that were to follow, it became a place of pilgrimage for art lovers stopping in Nairobi for whatever reason. The Pan-Africanist Art Gallery was the Mecca of cultural re-connection for performing artists, painters, writers, journalists, publishers and Africanists from Africa and the Diaspora.

The Paa ya Paa gallery was founded by a group of young, ambitious, artistic and creative men and women. On Fridays, Hilary Ng’weno and his wife Fleur, Mr and Mrs Pheroze Nowrojee, Terry Hirst, Jonathan Kariara, James Kangwana, Dr Josephat Karanja, and Elimu and Rebecca Njau, would meet at Rebecca’s house to discuss the one thing that was common to them all: media and artistic expression.

It is Kangwana (the unsung poet) who came up with the name Paa ya Paa at one of those Friday meetings. The young men and women were already established in life: Rebecca, who would later become an acclaimed author, was the first African headmistress of (Moi) Nairobi Girls.

Paa ya Paa gallery at Sadler House on Koinange Street was officially opened by Prof Bethwell Ogot.

Elimu, the Tanzanian-born Pan-Africanist painter and sculptor from Moshi had already shot to fame in 1959, when he became the first African artist to paint the mural of a Black Jesus that today adorns the Anglican Cathedral in Murang’a (then Fort Hall).

Kangwana was the first African Director of Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC) and the Harvard-educated Hilary had just become the youngest ever editor-in-chief of the Daily Nation, the Aga Khan’s flagship daily in East Africa that styled itself as a nationalist newspaper that had championed Kenya’s independence from British rule in its editorials and news gathering.

Kariara, one of the finest poets to come from this part of the world, was just emerging as a poet of note. With a PhD in History Dr Karanja was soon to serve as the first Kenyan High Commissioner in London. He was later to become the first Vice-Chancellor of the University of Nairobi.

Pheroze was a radical young Pan-Africanist lawyer scaling the legal heights as a human rights lawyer and political activist.

Terry Hirst, the illustrator-intellectual, had just landed from England to find Kenya savouring its new status as a newly independent state.

Before moving on to Rebecca’s, the group’s Friday meetings had been taking place at Elimu’s House at Maua Close in Parklands when he served as the Director of the (Captain Marlin) Sorsbie Art gallery.

Elimu put up a temporary studio at the back of the house in Parklands where he remembers inviting Ng’weno and Karanja to discuss art and even paint. “Hilary would do landscape painting and occasionally strum the guitar,” said Elimu nostalgically, recalling those heady and exciting days.

When the Sorsbie gallery closed in 1965, the Friday group finally found a permanent home in September of the same year: Paa ya Paa gallery at Sadler House on Koinange Street was officially opened by Prof Bethwell Ogot who was then Director of the East African Institute of Socio-Cultural Affairs based at Uniafric House. Paa ya Paa was domiciled in the city centre until the late 1970s when it moved to a five-acre piece of land in the Ridgeways residential area off Kiambu Road.

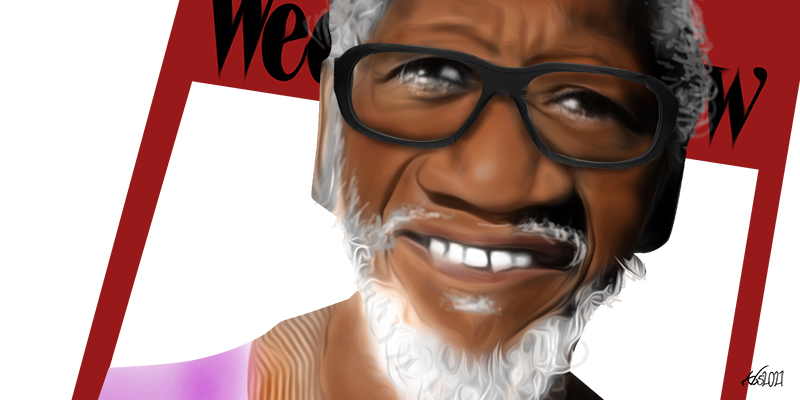

It was at this time that Ng’weno started his flagship weekly political magazine, the Weekly Review. By sheer coincidence, the launch of the weekly coincided with the announcement of the murder of JM Kariuki on 5 March 1975. The mutilated remains of the populist Nyandarua North MP had been “discovered” in Ngong Forest.

From then on, The Weekly Review became the standard-bearer for political news reporting in Kenya and the region. If you didn’t read the Weekly Review every Friday, you didn’t know what was happening in the country politically. So much so that a retired Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) official — now a mzee in his 80s who started working for the bank in 1966 when Duncan Ndegwa was appointed the first African governor — told me that senior staff were provided with the magazine so that they could keep abreast of political developments in the country. So important was the Weekly Review that it was considered the country’s political barometer.

So when Ngugi wa Thiong’o, a contemporary of Ng’weno and Ochieng, accused Ng’weno and The Weekly Review of “malicious” and “speculative” reporting on his detention in 1977, it provided Kenyans who read the weekly with a viewpoint that had not revealed itself before.

“I might here also as well mention the press hostility led by the Hilary Ng’weno group of newspapers and especially The Weekly Review,” wrote Ngugi in his prison memoir: Detained A Writer’s Prison Diary. “I was hardly out of prison when Hilary Ng’weno sent one of his reporters to interview me. But he had given her suspiciously leading questions and also instructions on how to go about it.”

If you didn’t read The Weekly Review every Friday, you didn’t know what was happening in the country politically.

Apparently, Ng’weno had written questions for the female reporter to raise with the author. “I looked at the questions and asked the reporter why her employers were interviewing me by proxy. I refused to be interviewed by proxy. She there and then conducted her own interview.” But Ng’weno was not yet done with Ngugi: “And when at long last, the whole interview was published, it was accompanied by the astonishing accusation that I was the only detainee who had not said thank you to the President for releasing me.”

Ngugi said, he “could not understand the source of this post-detention hostility, especially coming from a group of newspapers I had always supported because, despite their pro-imperialist line, I saw them as a hopeful assertion of a national initiative.”

In the diary, Ngugi accused Ng’weno of pursuing a speculative agenda on him: “What’s surprising is that The Weekly Review saw it fit to repeat the speculation even after my release!” The speculation being referred to here is that Ngugi had been detained because “of the Chinese and other literature found in his possession at that time of the police search in his study.”

“The aim of such speculative journalism as in Newsweek and Time magazines,” wrote Ngugi, “is to shift the debate from the issue of suppression of democratic rights and the freedom of expression, to a bold discussion and literary posturing about problems of other countries.” Ngugi said Ng’weno described him as an “ideologue” rather than a “writer”.

The Weekly Review of 9 January 1978 published that:

During the past year or so, Ngugi has acted the part of an ideologue rather than a writer. And has done so with increasing inability to relate in the limits of the sphere of an author’s operation which is possible in a developing country in areas where ideas, however noble, can be translated into actions which have far-reaching implications to the general pattern of law and order.

In the years that Ng’weno practiced newspaper journalism he styled himself as an apostle of press freedom and even though he was pro-establishment, he still got into trouble with Moi’s government.

In a memo he wrote to his staff on 19 October 1979, Ng’weno stated:

As we all know, we are having problems with the government at the moment. Most parastatal organisations have been instructed not to advertise with us anymore. As a result, a lot of advertising has been cancelled. We have not been told why this is being done and all efforts by me to get an explanation have failed so far. I do not know what the intentions of the government actually are, whether they want to kill our newspapers, or simply punishing us for something we have published.

The memo went on to say, “What I do know is that we cannot continue operating as we are now without advertising. Advertising is what makes it possible for a newspaper to survive or grow, without money from advertising, we cannot make ends meet.”

In the years that Ng’weno practiced newspaper journalism he styled himself as an apostle of press freedom.

Although The Weekly Review was supposed to be Kenya’s Newsweek, Ng’weno nonetheless styled the political magazine on the quintessential British magazine – the Economist. Just like at the Economist, writers at the Weekly Review did not have by-lines. To the great credit of Ng’weno and his team, it was impossible to tell who wrote what story from the names of the writers on the magazine’s masthead. Again, just like in the Economist, the writing styles were synchronised to present a uniform, distinctive style.

The Weekly Review had another distinctive feature: the editorial, which was written by Ng’weno until he ceded the space, was a short, pointed and punchy 500-word opinion written with candour and panache. Ng’weno used the same style that in his one-page Newsweek columns, in which he broached global topics as diverse as the Cold War, bilateralism and internationalism, neo-colonialism and patrimonialism. Ng’weno was possibly Newsweek’s only African columnist south of the Sahara.

The urbane, cosmopolitan Ng’weno walked with a swagger that told all and sundry that he was an Eastlando guy through and through. Kenyans who have interacted with Nairobians who grew up in the south-east of Nairobi where life, in Hobbesian maxim, is poor, nasty, brutish and short, know that they are street smart, witty, great seductors, agile, multilingual and multitalented, traits that the cool Ng’weno exhibited throughout his life.