India has been grappling with a deadly COVID-19 surge that hit the country like a cyclone in early April. Within a month, new daily cases peaked at over 400,000. On May 19, India set a global record of 4,529 COVID-19 deaths in 24 hours. Over 500 Indian physicians have perished from COVID since March. The actual figures on these counts are likely to be much higher due to testing limitations. Conservative estimates indicate India has experienced over 400 million cases and 600,000 deaths overall.

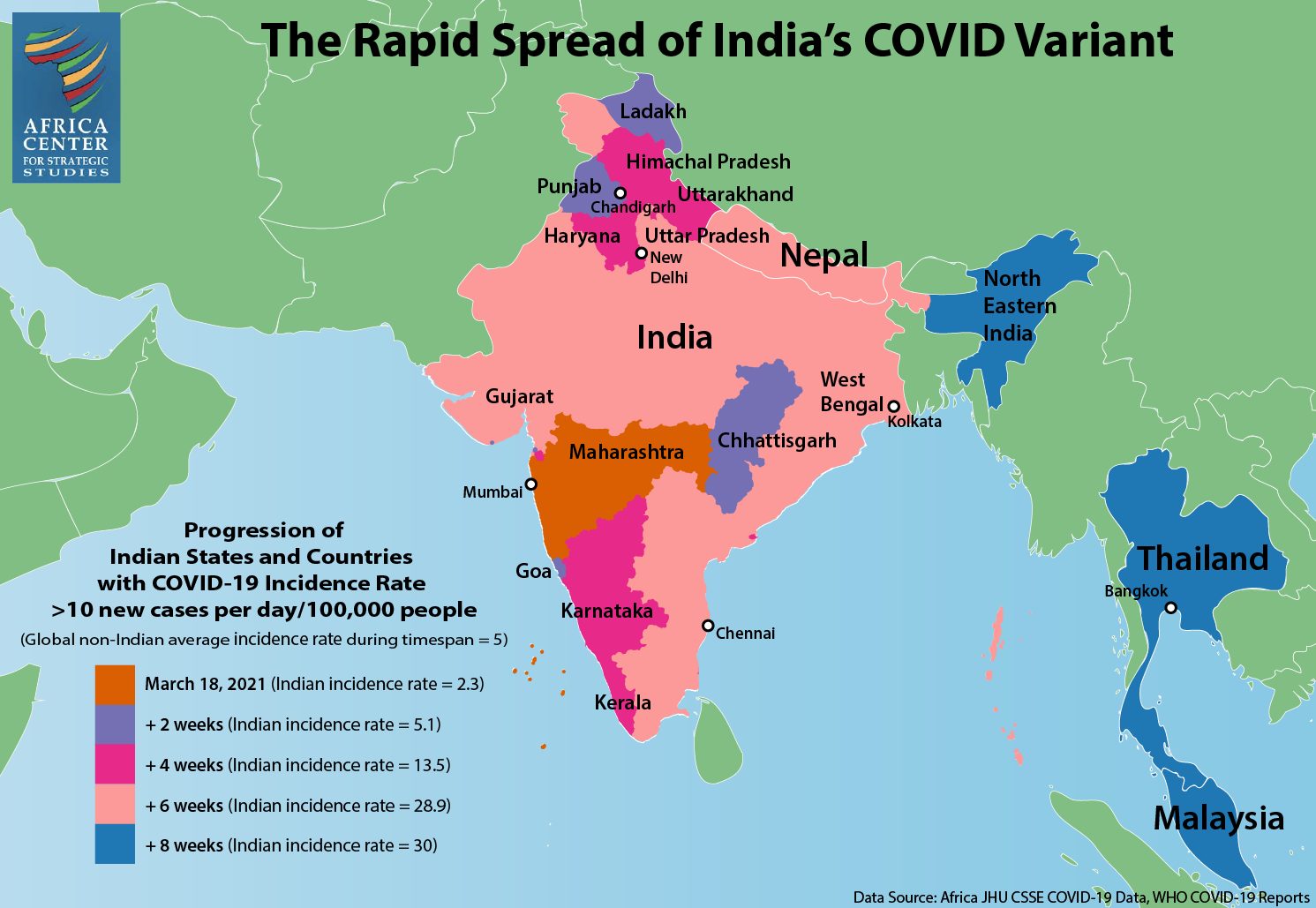

India’s hospitals are overflowing with patients in the hallways and lobbies. What hospital beds are available are often shared by two patients. Thousands more are turned away. Entire families in the cities are falling ill, as are whole villages in some rural areas. Countries in the region, such as Nepal, Thailand, and Malaysia, have also experienced a sharp uptick in cases fueled by the highly transmissible Indian variant.

India’s surge is also remarkable considering the country largely avoided the worst of the earlier stages of the pandemic.

India’s COVID-19 surge is a warning for Africa. Like India, Africa mostly avoided the worst of the pandemic last year. Many Sub-Saharan African countries share similar sociodemographic features as India: a youthful population, large rural populations that spend a significant portion of the day outdoors, large extended family structures, few old age homes, densely populated urban areas, and weak tertiary care health systems. As in India, many African countries have been loosening social distancing and other preventative measures. A recent survey by the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) reveals that 56 percent of African states were “actively loosening controls and removing the mandatory wearing of face-masks.” Moreover, parts of Africa have direct, longstanding ties to India, providing clear pathways for the new Indian variant to spread between the continents.

So, what has been driving India’s COVID-19 surge and what lessons might this hold for Africa?

The Indian Variant Is More Transmissible

In February, India was seeing a steady drop of infections across the country, and life was seemingly returning to normal. Unfortunately, this was just a calm before the storm. That same month, a new variant, B.1.617, was identified in the western state of Maharashtra, home to India’s largest city of Mumbai. Now widely known as the “Indian variant,” B.1.617.2 (or “Delta” variant according to WHO’s labeling) is believed to be roughly 50 percent more transmissible than the U.K. or South African variants of the virus, which, in turn, are believed to be 50 percent more transmissible than the original variant, SARS-CoV-2, detected in Wuhan.

Some experts say the emergence of B.1.617.2 represented a significant turning point. Within weeks, the new variant spread throughout southwest India and then to New Delhi and surrounding states in the north. Densely populated urban centers of New Delhi and Mumbai became hotspots. The virus then started spreading rapidly in poor, rural states across the country.

Medical professionals are saying the new variant is infecting more young people compared to the transmissions of 2020. Multiple variants are now circulating in India, including the Brazil (P.1) and U.K. (B.1.1.7) variants. Moreover, a triple mutant variant, B.1.618, has been identified and is predominantly circulating in West Bengal State. A triple mutant variant is formed when three mutations of a virus combine to form a new variant. Much remains unknown about B.1.618, though initial reports suggest it may be more infectious than other variants.

Complacency and the Loosening of Restrictions

When the COVID-19 pandemic emerged as a global threat in 2020, Indian authorities implemented a strict and early lockdown, educational campaigns on mask wearing, and ramped up testing and contact tracing where they could. However, since the peak of infections in September 2020, a public narrative started to emerge that COVID-19 no longer posed a serious threat. It was also believed that large cities had reached a measure of herd immunity. The relative youth of India and its mostly rural population that spends much of its time outdoors, further contributed to the sense that India had escaped the public health emergencies seen in other parts of the world.

“Government messaging during the first few months of 2021 boosted the narrative that India was no longer at risk.”

Government messaging during the first few months of 2021 boosted the narrative that India was no longer at risk. Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared victory over the coronavirus in late January. In March, India’s health minister, Harsh Vardhan, proclaimed the country was “in the endgame of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Behavioral fatigue also set in. Mask wearing waned, as did social distancing, all while tourism opened up and people began traveling to other parts of the country as in pre-pandemic times. Leaders in the western state of Goa, a popular tourist destination, began ignoring pandemic protocols and allowed entry to tens of thousands of tourists in an effort to bounce back from the economic fallout of the 2020 lockdown. Instead, Goa is believed to be the epicenter of the 2021 surge and now has one of the highest rates of infection in the country.

People began socializing in large gatherings elsewhere in the country as well. Contradictory COVID-19 protocols that called for strict night curfews and weekend lockdowns while simultaneously allowing large weddings and mass religious festivals only added to the collective sense of confusion and complacency. Contact tracing and follow-up in the field largely stopped.

Super-Spreader Events

India’s COVID-19 surge was also seemingly driven by a variety of super-spreader events. Most prominently were two international cricket matches in Gujarat State in western India where 130,000 fans converged, mostly unmasked, at the Narendra Modi Stadium.

Prime Minister Modi, himself unmasked, campaigned in state elections at rallies of thousands of maskless supporters in March and April. In West Bengal, where voting is held in eight phases, infections have since spiked.

Thousands gathered in the state of Uttar Pradesh to celebrate Holi, the weeklong festival of colors that began on March 29. Meanwhile, millions pilgrimaged to the Hindu festival Kumbh Mela in Uttarakhand State in April, which possibly led to “the biggest super-spreader [event] in the history of this pandemic.” Leaders in Uttarakhand not only allowed the festival to take place but also openly encouraged attendance from all over the world saying, “Nobody will be stopped in the name of Covid-19.”

Warning for Africa

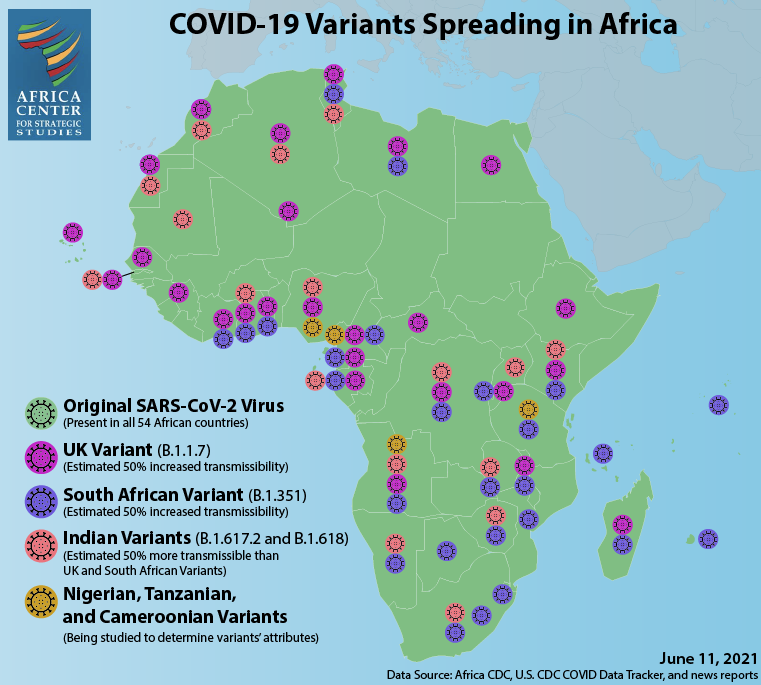

The recent surge in COVID-19 cases in India underscores why African countries cannot let their guard down or succumb to myths that cast doubt on how to bring the pandemic to a halt. Most directly, the Indian variant has already reached Africa. It was first detected in Uganda on April 29, 2021, and is now circulating in at least 16 African countries. Moreover, hospitals and ICUs in Uganda are now reporting an overflow of cases linked to the Indian variant. Many of the incoming patients are young people. India also shares similar social features with Africa: a young population, extended family structures that include caring for the elderly at home, and returning to less-populated rural areas of origin when crisis strikes.

Previous analysis has shown that there is not a single African COVID-19 trajectory. Rather, reflective of the continent’s great diversity, there are multiple, distinct risk profiles. Two of these risk profiles—Complex Microcosms and Gateway Countries—seem particularly relevant when assessing the Indian surge risk for Africa.

Complex Microcosms represent countries with large urban populations and widely varying social and geographic landscapes. Many inhabitants of countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Sudan, Cameroon, and Ethiopia live in densely populated informal settlements, making them particularly susceptible to the rapid transmission of the coronavirus. This group also has a higher level of risk due to their weaker health systems, which limits the capacity for testing, reporting, and responding to transmissions. Both the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria are among Complex Microcosm countries that have already detected the Indian variant.

Gateway countries, such as Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, and South Africa, have among the highest levels of international trade, travel, tourism, and port traffic on the continent. This makes them more exposed to potentially more infectious and deadly variants that have emerged from other parts of the world, such as India. The interconnected nature of South Asia and the African continent is seen by the early detection of the Indian variant in Algeria, Morocco, and South Africa.

India and the African continent have strong historical, cultural, and economic bonds. Roughly 3 million people of Indian origin live on the continent, and India is Africa’s second most important trading partner after China. Southern and East Africa, in particular, have deep ties to India and large Indian populations with families on both continents. In short, there are many economic and socially driven pathways for the Indian variant to reach Africa.

Priorities for Africa

Lessons from India show that its unprecedented COVID-19 surge was driven by both a more transmissible variant as well as by letting its guard down on preventative public health measures. This exposed the vulnerability of India’s closely integrated and densely populated demographics. A number of African countries also face elevated risks to the spread of the pandemic. Learning from India’s experience highlights several priorities for Africa.

Sustained Vigilance. Africa must remain vigilant since some of the same presumed protections India claimed, such as large rural populations that spend much of the day outside, may not guard against the next wave. The new Indian variants are spreading rapidly among young populations, and there is evidence that these newer variants, rather than just exploiting compromised immune systems, are causing some young healthy immune systems to overreact, resulting in severe inflammation and other serious symptoms.

This was the pattern observed in Africa during the 1918-1919 Spanish flu pandemic. The second wave of this pandemic was the result of a significantly more infectious and lethal strain that devasted the continent, infecting the young and the healthy. Countries outside Africa exposed to the mild first wave seemed to experience a reduced impact during the second wave, even though the two strains were markedly different. Having largely escaped the mild first wave, Africa was particularly vulnerable to the virulent second wave.

Continued Importance of Mask Wearing and Social Distancing. The strength of Africa’s public health system is its emphasis on prevention over curative care. African health systems do not have the infrastructure or supplies to respond to a crush of cases. Yet, many African countries have been actively loosening mask mandates and social distancing controls. On May 8, the Africa CDC hosted a Joint Meeting of African Union Ministers of Health on COVID-19 to encourage governments to overcome pandemic fatigue and invest in preparedness. With an eye toward India, prevention measures such as mask wearing, social distancing, and good hand hygiene are still as important as ever until vaccines become more readily available.

“Africa must remain vigilant since some of the same presumed protections India claimed, such as large rural populations that spend much of the day outside, may not guard against the next wave.”

Public Messaging. India suffered from confusing messaging at the early stages of the surge with prominent leaders and public health officials downplaying the severity of the risk and not modeling safe practices with their own behaviors. As they did with the initial onset of the pandemic, African leaders must convey clearly and consistently that the COVID-19 threat persists. Special outreach must be made to youth, who may feel they are immune, but who face greater risks from the Indian variant than previous variants that were transmitted on the continent. In cases where there is a low level of trust in government pronouncements, communication from trusted interlocutors such as public health practitioners, cultural and religious leaders, community leaders, and celebrities, will be especially important.

Ramping Up of Vaccine Campaigns. According to the Africa CDC, the continent has administered just 24.2 million doses to a population of 1.3 billion. Representing less than 2 percent of the population, this is the lowest vaccination rate of any region in the world. With the Indian and other variants coursing through Africa, the potential for the emergence of additional variants rises, posing shifting threats to the continent’s citizens. Containing the virus in Africa, in turn, is integral to the global campaign to end the pandemic. Recognizing the global security implications if the virus continues to spread unchecked in parts of Africa, the United Nations Security Council has expressed concern over the low number of vaccines going to Africa.

While this can largely be attributed to the limited availability of vaccines in Africa during the early part of 2021, this is changing. A number of African countries are now unable to use the doses they have available as a result of widespread vaccine hesitancy driven by myths surrounding the safety of the vaccines. Meanwhile, several African countries have not yet placed their vaccine orders with Afreximbank.

African governments and public health officials, therefore, need to ramp up all phases of their COVID-19 vaccine rollout—public awareness and education, identification of vulnerable populations for prioritization, and logistical preparations and outreach—for a mass vaccination effort to reach as large a share of their populations as possible. Africa’s well-established networks of community health workers provide a vital backbone as well as a trusted and experienced delivery mechanism to successfully achieve these objectives. With technical, financial, and logistical support from external partners, African vaccination campaigns can rise to meet the challenge.

–

This article was first published by the Africa Centre for Strategic Studies.