Kenya’s sugar industry circus continues. Late last year, the government formed a task force to look into the industry’s never-ending woes. Last week, a farmers lobby group formed a parallel task force, which is already convening in western Kenya and collecting views. The government has dismissed the private task force, and vice versa. Farmers seem to be behind the private one. Ironically, both are talking the same language— reviewing law and policy.

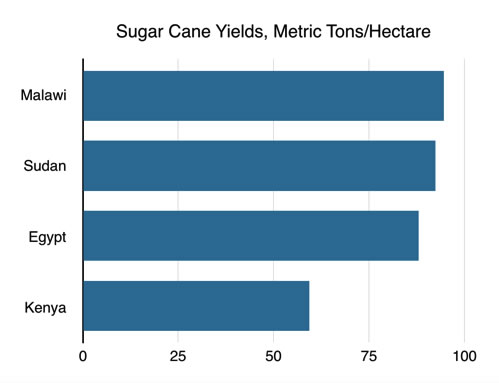

For more than a decade now, Kenya has been granted reprieves by the COMESA trade block to reform its sugar industry. Last year, the reprieve was extended for a further two years to 2020. The COMESA region has some very competitive sugar producers including Sudan and Malawi. Kenya runs a huge trade surplus with COMESA. Kenya’s excuses are wearing thin. This time round, the trade block set up a committee to supervise the implementation of the deal.

It is a tall order. Kenya’s sugar industry has a productivity problem. This has two components, low farm productivity and low sugar recovery. We have the lowest cane yields in the COMESA region (and the other COMESA countries have some of the highest yields in the world). The recovery rates are between 9 and 11 percent, that is, a tonne of cane produces between 90 – 110 kilos of sugar, while western Kenya manages to recover only 6 percent.

Why are cane yields in western Kenya so low? Simply put, this is because cane sugar production is a land and capital intensive crop. Western Kenya smallholders are land and capital poor. They don’t have the capital to invest in irrigation and high tech agronomy, or the scale to make such investments pay off. We do not leave the country to benchmark. Kwale International Sugar, the Mauritian investors who revived Ramisi Sugar report that they are harvesting 60 tonnes per hectare on rain fed cane, and 140 tonnes per hectare on irrigated fields. They describe their irrigation system as a “state-of-the art technology that includes a sub-surface drip-fed irrigation system which delivers 40 percent water saving.

We have the lowest cane yields in the COMESA region…the other COMESA countries have some of the highest in the world…

Assuming the rest of the agronomy is the same, irrigation alone more than doubles the cane yield. In fact, at 60 tonnes per hectare the rain-fed yield in Kwale is the same as western Kenya. However, cane at the coast matures faster, 12 months as compared to 15 to 18 months in western. This makes for significant productivity differences. In western, it translates to 120 tonnes per hectare over a three year cycle, which brings down the average annual production per hectare to 40, while in Kwale the yield and annual production remain at 60 tonnes per hectare. So, though we have 220,000 hectares planted, we only harvest 80,000 a year on average, which is just over a third of the planted acreage. To see the difference this makes, we produce on average 600,000 metric ton of sugar on 200,000 acres (440,000 acres) of land. Mauritius produces a similar about of sugar on 72,000 hectares (158,000 acres).

In economics, we think of resource allocation in terms of opportunity cost. The economic value of an industry is what it produces over the next best alternative use of the scarce resources that it employs. Kenya is a land-poor country. Only a third of the land is arable without considerable investment in irrigation and land improvement. The sugar belt is some of Kenya’s most productive rain-fed cropland. If the land under sugarcane could be made as productive as tea, it would generate $1.3 billion ( Sh.130 billion) at current exchange rates, compared to US$ 180 million worth of sugar currently.

By misallocating resources, western Kenya is losing KSh 100 billion worth of agricultural productivity. As a country we are losing more. Average ex-factory price of sugar is currently quoted at KSh 4,000 per 50-kg bag (KSh 80 per kilo) which translates to US$ 800 per tonne. Sugar is trading at about $280 a tonne, or KSh 30 per kilo in the world market. Kenyan consumers are paying more than double the world price. With current consumption at 80 kilos per household, the sugar industry protection works out to KSh 4,000 per household per year. If we were buying sugar at the world price, the savings would be enough to buy every Kenyan household a kilo of meat every month.

By misallocating resources, western Kenya is losing KSh 100 billion worth of agricultural productivity.

We pay western Kenya more than double the world price of sugar, but it has not made the region prosperous. All the public sugar companies are insolvent. The government and stakeholders continue to go round in circles. Waswahili have a popular saying “ukiona vialea vimeundua” (ships/vessels float because they are build to), meaning there are reasons why things are what they are.

After independence, the government set about identifying cash crops that smallholders could grow in the different “high potential” agro-ecological zones. Central Kenya had coffee, tea and pyrethrum. The white highlands had their cereals and dairy. In line with the import substitution industrialization strategy of the time, sugar and cotton were identified as ideal cash crops for the lake region. It is the misfortune of western Kenya that both crops were unsuited for a smallholder out-grower production system. To be sure, it is pure good luck that tea turned out to be suited for the model. In fact, the World Bank strongly advised the government against it, as there was no precedent of smallholder tea production anywhere in the world.

The sugar industry thrived behind the tariff barriers of import substitution industrialization. But by the mid-seventies, the structural and economic challenges that now plague the industry were already in place. Prof. Stephen Mbogoh, one of the country’s leading agricultural economists, who studied the sugar industry for his doctorate observed:

“At the macro-level planners are interested in other aspects of an enterprise, besides the profitability aspect. The potential for an enterprise to create employment in Kenya, particularly in the rural areas, is an important consideration. Cane production is found to be the most profitable enterprise, but it does not generate as much capacity for absorbing the rural unemployed as the alternative enterprises.” (Mbogoh, Stephen Gichovi. An Economic Analysis of Kenya’s Sugar Industry with Special Reference to the Self-Sufficiency Production Policy PhD Thesis. University of Alberta. 1980)

Mbogoh’s analysis showed that sugar had the highest income per worker, but the lowest job creation potential of the competing alternatives (See table). But this analysis does not bring the import protection factor to bear. Even then sugar was the most highly protected of the alternatives. From Mbogoh’s data sugar was retailing at KSh. 4.50 per kilo in 1976, which works out to US$ 750 per tonne, against a world price of US$ 250 per tonne— the same as now. If both the domestic resource cost (i.e. the cost of protection) and job creation were taken into account, the maize/groundnut combination would have come out on top. It is worth noting that even with import protection, the maize/groundnut gross revenue is comparable to sugarcane.

Mbogoh’s analysis showed that sugar had the highest income per worker, but the lowest job creation potential of the competing alternatives (See table). But this analysis does not bring the import protection factor to bear. Even then sugar was the most highly protected of the alternatives. From Mbogoh’s data sugar was retailing at KSh. 4.50 per kilo in 1976, which works out to US$ 750 per tonne, against a world price of US$ 250 per tonne— the same as now. If both the domestic resource cost (i.e. the cost of protection) and job creation were taken into account, the maize/groundnut combination would have come out on top. It is worth noting that even with import protection, the maize/groundnut gross revenue is comparable to sugarcane.

After independence, the government set about identifying cash crops that smallholders could grow in the different “high potential” agro-ecological zones. Central Kenya had coffee, tea and pyrethrum. The White Highlands had their cereals and dairy. In line with the import substitution industrialization strategy of the time, sugar and cotton were identified as ideal cash crops for the lake region. It is the misfortune of western Kenya that both crops were unsuited for a smallholder out-grower production system.

From an economic policy standpoint, gross revenue is a more important variable than the net profit because it captures all the incomes generated by an economic activity and not just the profit of that specific enterprise. The difference between gross and net income captures the multiplier effect of an enterprise. In this case, we see that while both sugarcane and the maize/groundnut option have roughly the same gross income, the maize/groundnut options buys 60 percent more (KSh 2,122) than sugarcane (KSh 1,296), which is indicative of a better distributional outcome than sugarcane.

By the mid-seventies, the structural and economic challenges that now plague the industry were already in place.

In summary the policymakers saddled western Kenya with an uncompetitive, capital intensive, low productivity, regressive (i.e. income concentrating) cash crop. One cannot help but wonder whether the predominance of western Kenya migrant labour in Nairobi has something to do with these policy choices.

In all fairness, this was not, as is sometimes insinuated, a conspiracy to impoverish the region. Rather, it was a reflection of the conviction behind import substitution industrialization. Indeed, the import substitution strategy was predicated on “export pessimism” – the idea that primary commodity exporters were condemned to deteriorating terms of trade (purchasing power vis-a-vis manufactured goods) in perpetuity. Viewed from this perspective, western Kenya with its sugar and cotton mills seemed brighter than that of primary commodity exporting central Kenya.

Policymakers saddled western Kenya with an uncompetitive, capital intensive, low productivity, regressive cash crop. One cannot help but wonder whether the predominance of western Kenya migrant labour in Nairobi has something to do with these policy choices.

By the end of the 70s, import substitution had run its course. Subsidies drained government coffers, and the imports of machinery and raw materials required to keep the industries afloat depleted foreign exchange without generating any. In Sessional Paper No.1 of 1986, Economic Management for Renewed Growth, the Moi government acknowledged that it was at the end of the road. Gradual liberalization began then, and ended with a bang in 1993. The textile industry, and cotton farming were wiped out.

But the sugar industry survived. How come? To the best of my knowledge, this question has not received much academic attention, but I have a theory. Cotton was by and large a poor man’s crop. Sugarcane outgrowers are both rich and poor. According to Prof. Mbogoh’s study, large scale outgrowers farming 40 to well over a 1000 hectares accounted for 40 percent of the outgrower acreage, and smallholders with between one and six hectares for the other 60 percent. I suppose that the sizes will have changed as land has become fragmented but the industry structure remains more or less the same.

Liberalization…ended with a bang in 1993. The textile industry, and cotton farming were wiped out. But the sugar industry survived. How come?

Because sugarcane production is capital intensive, the large scale outgrowers are able to achieve higher farm productivity than smallholders, but still benefit from the cane prices that are based on the smallholders cost structure. Moreover, the low husbandry requirements between planting and harvesting makes sugarcane very amenable to “telephone” farming by western Kenya elites. Additionally, the same said elites have preferential access to other business opportunities in the value chain, such as suppliers to the factories and sugar distribution. It is instructive that Mumias, which stands out by not having large scale outgrowers, was the only sugar company that was privatized, perhaps because there were no powerful elites with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. From this vantage point, the private task force begins to look more like a “steak holder” than a stakeholder initiative.

Because sugarcane production is capital intensive, the large scale outgrowers are able to achieve higher farm productivity than smallholders, but still benefit from the cane prices that are based on the smallholders’ cost structure.

But western Kenya’s sugar industry cannot be protected from competition indefinitely. Sooner or later, the COMESA safeguards will come to an end. If not that, other domestic producers will follow KISCOL and cash in on the high prices with lower costs of production. And as long as the wedge between the international and domestic prices remains what it is, episodes of import deluges will continue to destabilize the industry. The time for western Kenya sugar industry to face reality is now.

Steak holders should let the people go.