Ten years ago, an anonymous person or people known as Satoshi Nakamoto published a paper announcing a monetary innovation described as a peer-to-peer electronic cash system. “Peer-to-peer” means a system of exchange that does not require intermediaries, such as banks, to function. When we use a card to buy something at the supermarket, the holder’s account is debited and the account of the merchant is credited. There are at least three intermediaries to this transaction namely, the card-holder’s bank, the supermarket’s bank and the card issuer all who make some money from it, and there is of course the governments which are the ultimate guarantors of the payment systems we use.

The system devised by Satoshi Nakamoto known as Bitcoin became the progenitor of cryptocurrencies. Instead of the accounting systems of banks and other intermediaries, the cryptocurrency systems use a digital public register, known as a blockchain. When people transact, the transaction appears on the public register. The transaction’s security and validation services that we rely on: banks, card issuers, central banks and lately telcos and “fintechs” in the case of mobile phone payments platforms, is done by techies called “miners” who compete to verify transactions by solving puzzles. The miner who completes the verification first earns some bitcoins. So in effect, the claim that there is no third party intermediary is not quite accurate. What they have done is to replace centralized systems and authorities with a decentralized free-for-all system.

Bitcoin appeared have settled at around $1000 up until January 2017, when it began what was to become an unprecedented rise. In December 2017 it peaked at a little over $19,400. A year later it is down to under $4000. Bitcoin is now billed as the most spectacular financial bubble on record.

At the height of the cryptocurrency boom, enthusiasts were declaring fiat currencies history. Fiat money is a currency decreed by governments to be the “legal tender” in its jurisdiction and is one of three types of money that have existed in history. The other two are commodity and credit money. Commodity money is something of intrinsic value such as precious metals that is generally accepted for payment. Credit money arises when debt instruments typically issued by a reputable party such as a bank, wealthy enterprise or government becomes accepted for payment. The word “banknote” originates from the “free banking era” in the US, when promissory notes issued by banks were generally accepted as means of payment. Today’s prominent fiat currencies such as the US dollar began life as promissory notes issued by governments mostly to finance wars.

Bitcoin appeared have settled at around $1000 up until January 2017, when it began what was to become an unprecedented rise. In December 2017 it peaked at a little over $19,400. A year later it is down to under $4000. Bitcoin is now billed as the most spectacular financial bubble on record.

As Bitcoin soared, Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) began to look uncannily like the prospectuses of South Sea Bubble companies (such as my personal favourite: “For carrying out an undertaking of great advantage; but nobody to know what it is”). Economists, who pointed this out, including this columnist, were dismissed as luddites who were stuck in old school thinking. Cryptocurrency and blockchain were the ultimate technological disrupter. We were on the cusp of a new economic architecture where the old rules would no longer apply.

Today’s prominent fiat currencies such as the US dollar began life as promissory notes issued by governments mostly to finance wars.

The cryptocurrency techno-warriors may yet have the last laugh. But to do that they would do well to learn a thing or two about the competition.

Literature review for tweeps seeking bitcoin advice:

Tulip Mania

Mississippi Company

South Sea Bubble

Dotcom bubble— David Ndii (@DavidNdii) December 8, 2017

Up until they were colonized a century ago, my Agikuyu forebears were moneyless. In Elspeth Huxley’s irreverent parody of the Agikuyu’s early encounters with Europeans Red Strangers, this is what ensues when Muthengi is offered a job that pays five rupees a month:

“I do not want these metal objects,” Muthengi answered. “What can I do with them? Why does he not give me goats?”

“It is the same as if he gave you goats” the interpreter said. “You can exchange rupees for goats.”

“How many are needed to obtain a goat?”

“One rupee will buy one goat?”

Muthengi could conceal his incredulity no longer. It was impossible to believe that the world held anyone so foolish as a man who would surrender a goat for a useless piece of metal possessed, it seemed, of no magical powers. But the thought of five goats a month burrowed like a mole underneath Muthengi’s mind. It seemed incredible, yet what if it could be true? Five goats a month, thirty goats a season, two hundred and ten goats in four seasons with the increase of one to each female in a season…it was impossible to encompass so many goats with the mind’s eye.

Muthengi accepts, dutifully converts his five rupees pay into goats every month, and becomes very rich.

In economics, we tend to look at money like Muthengi. Since money is not of itself productive people ought not hold on it longer than necessary, they would convert it to goats as soon as they are able. Money would be constantly changing hands, lubricating commerce. Why then, is money such a big deal?

To study questions like these, economists sometimes resort to reverse engineering to see whether we can build a model in which the thing in question arises “endogenously.” By “endogenous” we mean that it is not introduced by an outside agent, such as the mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto.

As Bitcoin soared, Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) began to look uncannily like the prospectuses of South Sea Bubble companies. Economists who pointed this out were dismissed as luddites who were stuck in old school thinking. Cryptocurrency and blockchain were the ultimate technological disrupter. We were on the cusp of a new economic architecture where the old rules would no longer apply… The cryptocurrency techno-warriors may yet have the last laugh. But to do that they would do well to learn a thing or two about the competition.

Students of economics know that money serves three functions: a medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value. Our earliest ancestors were hunter-gatherers. We do not know for sure whether hunter-gatherers invented money. It is not evident that small bands of hunter-gatherers would find need to invent a medium of exchange, or units of account.

But one thing we are sure of is that hunter-gatherers grew old. They would have had to figure out some means of surviving in old age. One of these is to cultivate social bonds which obligate progeny to provide for the elderly. This is quite evidently true, but it is not entirely sufficient since not everyone will have children, and it is far from certain that children will survive to support their parents in old age. Thus, kinship-based old age security will result in some old people enjoying good care from their progeny, and others dying of destitution, quite an unsatisfactory situation.

Trading seems to be one of the things that we do naturally. Two hunter-gatherers, one who has caught an antelope and the other has harvested wild honey bump into each other on the way home. Can I have some of that, for some of this? Markets enable strangers to meet each other’s needs. Can the market find a solution for the old age security problem?

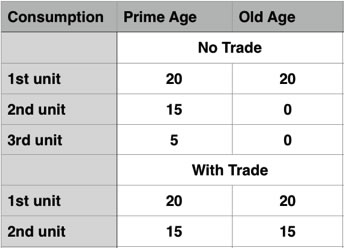

Now, imagine a small hunter-gatherer community with a population of two hundred people. Each person lives for two periods, youth and old age, and is endowed with three units of a consumption good, manna from heaven if you like, when young and one unit when old. As per the law of diminishing returns, consuming the first unit yields 20 units of happiness, the second yields 15 and the third yields 5 units. As shown in the table, if each person consumes only their endowment, they enjoy 60 units of happiness. If they can trade so that each person consumes two units in each stage, each person would enjoy 70 units of happiness in their lifetime.

Now, imagine a small hunter-gatherer community with a population of two hundred people. Each person lives for two periods, youth and old age, and is endowed with three units of a consumption good, manna from heaven if you like, when young and one unit when old. As per the law of diminishing returns, consuming the first unit yields 20 units of happiness, the second yields 15 and the third yields 5 units. As shown in the table, if each person consumes only their endowment, they enjoy 60 units of happiness. If they can trade so that each person consumes two units in each stage, each person would enjoy 70 units of happiness in their lifetime.

In economics, we tend to look at money like Muthengi. Since money is not of itself productive people ought not hold on it longer than necessary, they would convert it to goats as soon as they are able. Money would be constantly changing hands, lubricating commerce. Why then, is money such a big deal?

This set up is called an overlapping generations model and is one of two devices that economists use to study long run economic dynamics (the other one is called an infinite horizon model). It was formulated by French economist Maurice Allais and refined by Paul Samuelson in a seminal 1958 paper titled A Consumption Loans Model of Interest with or without the Social Contrivance of Money. My set-up here conveys the gist of Samuelson’s model but the formulation and parameters are my own.

If the community can find a way to trade, everyone will enjoy 10 more units of happiness. One way of thinking about this is as an increase in life expectancy from 60 to 70 years. The problem with this trade is that it cannot be conducted bilaterally, peer-to-peer if you like. The young can support the old today, who will then die. For their own old age security, they will need the support of the next young generation which is as yet unborn. However, if society were to device a voucher, a receipt if you like, that is given to each prime-age adult in exchange for giving up one consumption good unit to support an old person, they can trade vouchers with the subsequent generation.

Be it a strip of buffalo hide, or a string of cowrie shells, a social security card or a promissory note, it stands to reason that once it’s invented each successive generation will value them, since everyone will also need to secure their old age with the successor generation. Individuals need no longer fear old age destitution on account of not having family support in their old age. In fact, this market system could have the unintended consequence of undermining the kinship system, as Alessandro Cigno observes in his book Economics of the Family:

“the growth of the financial sector (including in that the social security system, as well as banks, private insurance and the stock exchange) tends to coincide, in the development of an economy, with a sharp fall in fertility, the break up of extended family networks and a widespread reluctance on the part of the middle aged to accept responsibility of elderly relatives.”

Now that we have a theory of money, we can examine what attributes sound money should have. First, it needs to be trusted. Every voucher must be a legitimate store of value. It is not difficult to see that people entrusted with its production may be tempted to game the system by producing more vouchers than needed, and some people will find themselves with vouchers that command less than what they put it. Second, it should be possible to increase the number of vouchers in tandem with the population growth To see this, let us suppose the next generation increase to 110 people, an additional ten vouchers will be needed otherwise some of its members will be locked out of the intergenerational trade.

What then, are the lessons to be learned by people seized with the idea of re-inventing money?

One of the key requirements of sound money is a credible supply rule. In our simple model, the anchor is population growth. But it so happens that in our model population growth and economic expansion are identical, therefore it is the same as a money supply rule that is anchored on the size of the economy. Satoshi Nakamoto decreed that the bitcoin algorithm would cease after 21 million of them were mined. Why 21 million? Nobody seems to know. In effect, as a currency, bitcoin had the same flaw that undermined gold and silver, namely arbitrary supply that is unrelated to demand.

A second flaw is the tech-hype the cryptocurrency as the ultimate disruptive technology that would liberate society from the state-financial capitalist stranglehold. Because the value of technology innovations is highly uncertain, the value of bitcoin became entwined with people’s subjective guesses and predictions of what that value might turn out to be, as opposed to the economic fundamentals. We call this a sunspot equilibrium. For an asset purporting to be money, it is a highly undesirable attribute. It is this particular flaw that fueled the speculative bubble. This eventuality could have been mitigated by creating two assets: one that would profit from the innovation and one that reflected the economic fundamentals.

One of the key requirements of sound money is a credible supply rule. In our simple model, the anchor is population growth. But it so happens that in our model population growth and economic expansion are identical, therefore it is the same as a money supply rule that is anchored on the size of the economy. Satoshi Nakamoto decreed that the bitcoin algorithm would cease after 21 million of them were mined. Why 21 million? Nobody seems to know.

The third and perhaps fatal flaw is that cryptocurrency inventors failure to appreciate that fundamentally, money is a social contract. Social acceptance is what makes cowrie shells, beaver pelt, silver, gold or pieces of paper issued by government a currency. Of all our social contrivances, the one that money shares most attributes with is the state. It should not surprise then, that money has evolved into government-issued fiat currencies. But just like in governing, it does not mean that governments will excel in monetary affairs. In fact, the quality of a country’s money and governance tend to be closely correlated. Robert Mugabe’s ZANU-PF regime is but the latest to make a mess of both.

Monetary delinquency is one of the surer harbingers of revolution. If government makes a mess of our money, we can always behead the King. Which is just as well that Satoshi Nakamoto had the foresight to be anonymous. Could be he/she/they knew something that their starry-eyed cryptocurrency enthusiasts did not.