The March 9, 2018 handshake between Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga, silenced many of the critical voices accusing the Jubilee coalition of divisive politics, ethnic bigotry and the disenfranchisement of at least half of Kenya’s population. In fact, for a brief moment it seemed that the bitter grievances of the disputed August 2017 election, the acrimonious exchanges between political rivals, the threats to the judiciary, the unsolved murder of IEBC’s Chris Msando, and the police killings in the post-election crisis, had been forgotten following the very-closed-door meetings between Uhuru and Raila. As a writer with the Daily Nation gushingly wrote a week later: ‘In the name of that handshake, the shilling has stabilised overnight with the outlook by players in tourism already promising what some experts have christened as the ‘peace dividend’ after an inordinately protracted electioneering period. The stock market is also recovering’. Despite the ceasefire of the handshake, its promised benefits have not cleared the dark clouds hanging over the Kenyan economy, which is now headed into serious difficulties. In fact, at a practical level there appears to be no change in the way the national government runs its day-to-day affairs.

Since coming to power in 2013, the Jubilee administration has been dogged by accusations of profligacy and patronage – most notably in the award of tenders. Policy-making, with senior public officials apparently motivated more by personal interests than by public service, and even outright nepotism and tribalism, spurious contracting in the implementation of policy initiatives in the key sectors of health, agriculture and infrastructure.

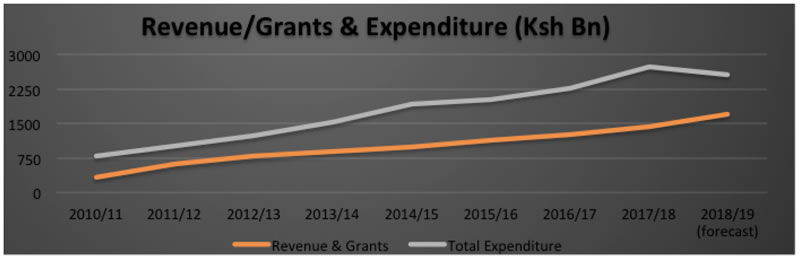

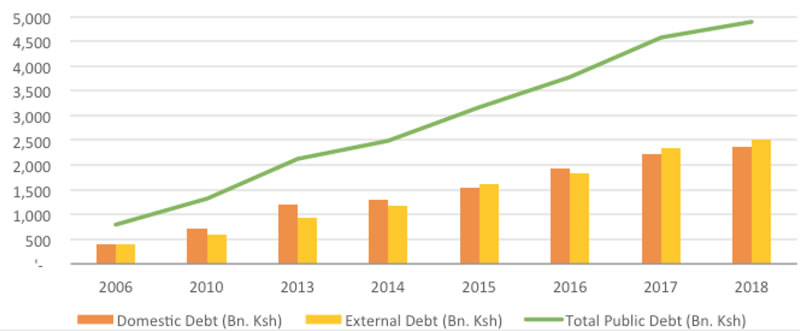

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the Jubilee administration has also presided over a massive debt-fuelled increase in annual public spending – KSh 1.2 Trillion to over KSh 2.5 Trillion in 6 years, complemented by a budget deficit approaching Ksh 750 billion (see Table 1). Notably, this growth in spending is at a rate beyond the GDP growth rate and, as far as many critics are concerned, has been partly motivated by the need to accommodate corrupt patronage practices. Spending on infrastructure programmes in particular, seamlessly lends itself to patronage and has been a dominant feature of Jubilee’s tenure, with a range of big-ticket projects in the transport, energy and health sectors. Recurring elements of these projects include secretive feasibility studies, procurement and financing arrangements, as well as questionable labour deployment and land acquisitions – all of which embody the controversial SGR Railway project which has taken up the lion’s share of this spending binge.

Spending on infrastructure programmes in particular, seamlessly lends itself to patronage and has been a dominant feature of Jubilee’s tenure, with a range of big-ticket projects in the transport, energy and health sectors. Recurring elements of these projects include secretive feasibility studies, procurement and financing arrangements, as well as questionable labour deployment and land acquisitions.

Table 1.

Table 1.

Jubilee’s Treasury team however, has maintained that the increase in public spending was and remains necessary to spur economic growth. Treasury has systematically played down the risks from the widening budget deficit in the process. This surge in spending – financed mostly with (Chinese) debt – has also taken centre stage in the cooling relations between the government and development partners, notably the IMF and World Bank. Critical to debate on this spending surge and the risks from a widening budget deficit is its impact on the performance of the Kenyan economy.

In particular, why have key sectors of the economy registered such diminished performance over the past half-decade in the face of this increased spending? Why does so much anecdotal evidence point to growing job-layoffs (an estimated 7,000 formal sector jobs have been lost in the past three years alone)? Even the normally bullish real estate market has shown signs of glut and slowdown over the past three years. The Nairobi Securities Exchange has seen its NSE 20 index climb from slightly over 4,000 in 2013 to a high of 5,400 in 2015, before falling to about 3,400 today. The Stock Exchange, without a single IPO listing since 2014, has seen more than half of all listed companies declare reduced earnings or losses in each of the past two years.

Why have key sectors of the economy registered such diminished performance over the past half-decade in the face of this increased spending? Why does so much anecdotal evidence point to growing job-layoffs (an estimated 7,000 formal sector jobs have been lost in the past three years alone)?

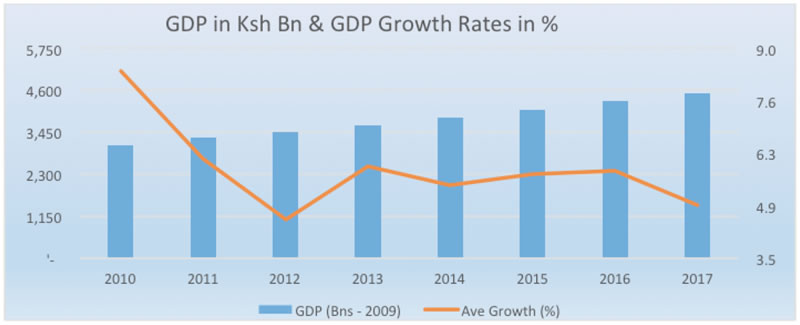

Table 2 below shows Average GDP Growth rates (RHS Scale) over the past 8 years and actual GDP (Using Constant 2009 Prices LHS Scale).

Whereas average GDP growth rates have averaged 5.8 percent over the period shown, the downward trend since 2010 has persisted despite the huge increase in spending – and this is despite GDP-rebasing in 2013 which enhanced the growth rate that year by at least 1%. Both 2013 and 2017 were election years and unsurprisingly, registered the lowest growth rates; but the increased government spending – albeit on long-term projects – appears to have actually had a dampening impact on GDP growth over the period. There are several reasons for this, but three key issues are highlighted here.

1. An unremunerated Private Sector.

Accusations of partisanship and gravy-train policy-making in the award of public tenders and contracts, are not just the grumblings of out-of-favour business-people that lost out on lucrative government business to well-connected or favourably-related individuals. There is a constituency of ordinary hard-working entrepreneurs, professionals and manufacturers increasingly unable to compete against the empowered cartels of tenderpreneurs, influence peddlers and brief-case businessmen. These rogue players currently dominate government contracting – not to mention annual auditor-general reports – making a mockery of procurement guidelines. In some instances they even approach qualified bidders, offering to be embedded in bidding teams (despite the lack of relevant competencies) with a promise of tender success at inflated bids. This patronage-based ‘crowding out’ doesn’t end there. This well-connected class of tenderpreneurs also has perfected the dark art of jumping bureaucratic payment queues, often receiving payments before delivery of goods and services – or even before contracts are signed.

Not by coincidence, legitimate suppliers, service providers, and even farmers, have been experiencing debilitating delays in the settlement of payments and have accumulated massive debts on their credit arrangements and tax obligations. The paradox is that while government department budgets were being ramped up, delays in contract awards and settlement of payments to legitimate suppliers were worsening. This has created a unique set of economic challenges that seems to have been lost in all the discussions on political handshakes.

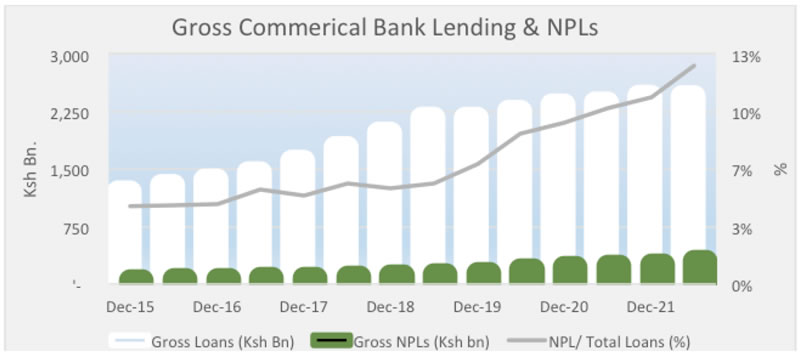

According to the Central Bank of Kenya, Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) as a proportion of total lending by commercial banks doubled from 6.1 percent in 2015 to 12.4 percent (or about KSh 265 billion) by April 2018 (see Table 3 below). The Table shows Gross Lending by Commercial Banks as well as the stock of Non-Performing Loans, as well as the stock of Non-Performing Loans expressed as a percentage of Gross Lending by Commercial Banks. Even this 12.4 percent figure could be an under-statement if banks have not been adequately disclosing and providing for non-performing loans – as suggested by the sagas of the collapsed Imperial and Chase Banks.

Table 3

Table 3

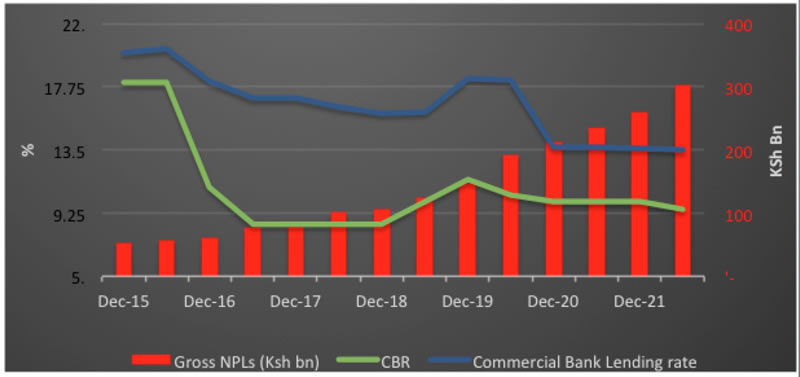

CBK Governor Patrick Njoroge attributes a significant factor in this growth in bad loans to delayed payments owed to the private sector by the national government, government departments and devolved units. CBK data suggests that up to KSh 200 Billion was owed to SME businesses by the national government by the end of the 2017/2018 Financial Year, with as much as KSh 25 Billion worth of those pending bills directly contributing to non-performing loans.

Following an increase in imported grains last year (amid accusations of pre-election giveaways), the National Cereals and Produce Board (NCPB) owed farmers as much as KSh 3.5 Billion by the end 2017 for produce already delivered. In a hard-hitting editorial on 7th August 2018, the Daily Nation averred, ‘The Jubilee government is wallowing, not just in foreign debt, but also in the money it owes local businesses, which it has either crippled or is in the process of ruining’.

According to the Central Bank of Kenya, Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) as a proportion of total lending by commercial banks doubled from 6.1 percent in 2015 to 12.4 percent (or about KSh 265 billion) by April 2018. The Table shows Gross Lending by Commercial Banks as well as the stock of Non-Performing Loans, as well as the stock of Non-Performing Loans expressed as a percentage of Gross Lending by Commercial Banks. Even this 12.4 percent figure could be an under-statement if banks have not been adequately disclosing and providing for non-performing loans.

The Daily Nation’s particular beef was that the Government Advertising Agency (GAA), owed media houses close to KSh 3 billion by the end of FY 2017/2018. About half of the KSh 404 Million paid out by GAA during the year, went to the big publishing houses – Nation Media Group, Standard Newspapers, Royal Media Services, The Star and Media Max Network. Against the KSh 3 billion owed, the distribution of payments to media houses was sufficiently skewed to warrant an investigation by the Office of the Public Prosecutor.

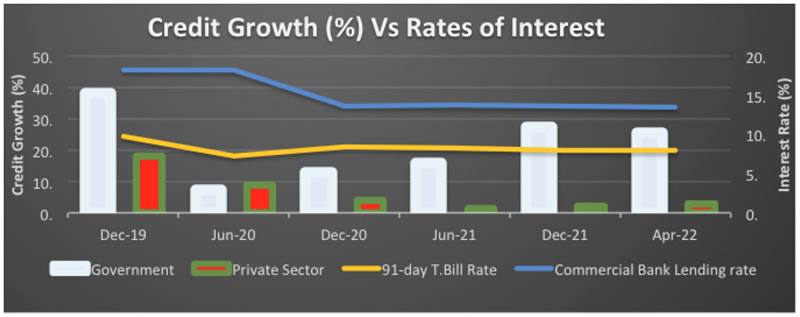

Worryingly as well, the increase in bad loans in the banking sector has come despite the implementation of August 2016 of lending rates ‘caps’, which limit the cost of existing loans to 4 percent of the Central Bank’s Recommended Rate. (See Table 4)

2. A Stifled Private Sector

This environment of pending government bills is also linked to worsening Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) tax collection performance. This creates a vicious cycle in which the private sector is defaulting on its obligations on account of money owed by the same government. The government has long complained about KRA’s inability to meet its collection targets, complaining instead about ‘revenue leakages’ facilitated by corrupt tax officials. But it fails to acknowledge that its pursuit of tax defaulters is a consequence of the fact that they themselves are owed millions by national and county governments.

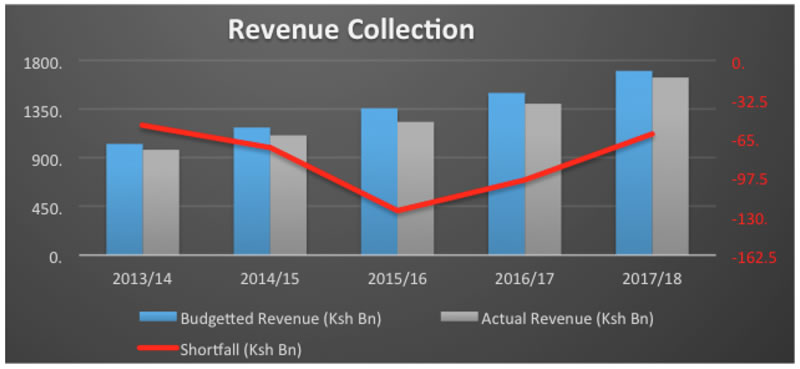

The reality is that National Government revenue shortfalls have averaged KSh 90 Billion annually over the past 4 years, despite improved tax collection efficiencies at the KRA. (See Tables 5 & 6 below.) The World Bank estimated that in the 2016/2017 financial year, tax revenue as a proportion of GDP fell to under 17%, the lowest in a decade – with the growth in nominal Tax Revenues outpaced by nominal GDP growth.

Table 5

Table 5

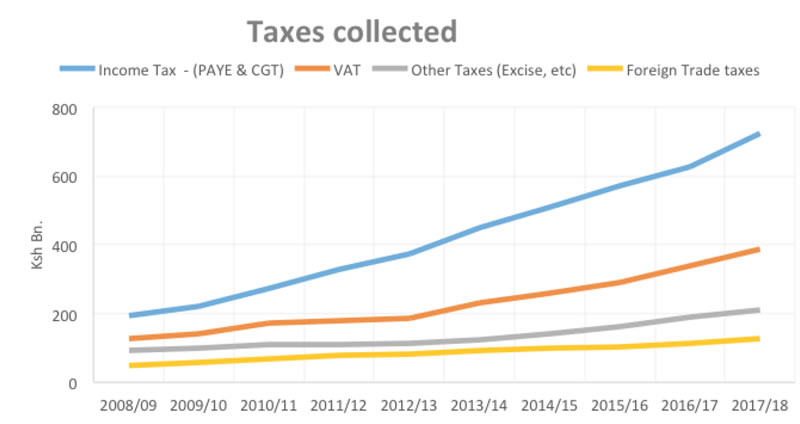

This reduced growth rate of revenue collection by KRA is at first glance paradoxical considering that over the past 5 years, an unprecedented number of Kenyans have been brought into the tax bracket. A similarly unprecedented range of products and services have been subjected to various new direct and indirect taxes. Over the past five years, several tax measures have been introduced including: 12 percent Rental Income tax for landlords from 2015; successive excise duty and fuel levy increases in 2015, 2016 and 2018; VAT on bottled water and juices; VAT on food served by restaurants as well as piped water; successive increases in excise duties on spirts, cigarettes and mobile telephony; and 50 percent Gaming tax on lotteries and book makers in 2017, among a host of others. The 16 percent VAT on fuels and fuel oils first awarded in 2013 but deferred over the subsequent years with the exemption set to expire on 1st September 2018, adds a controversial element to this expanded tax net aimed at bringing the growth in VAT collections closer to that of direct taxes such as PAYE and Income Taxes (see Table 6).

Table 6

Table 6

In his June 2018 Budget statement, Finance CS, Henry Rotich, laid out several new and controversial ‘Robin Hood Tax’ proposals which he declared necessary to fund programmes that are part of Jubilee’s ‘Big 4’ agenda. Prominent among the proposals purportedly designed to protect low-income earners, is a monthly contribution to a nebulous National Housing Development Fund by every employee and employer of 0.5% (capped at KSh 5,000) of the employee’s gross pay. This contribution would be funnelled to the Housing Fund whose mandate will be to build low-cost housing units. Another ‘Robin Hood Tax’ proposal was the levying of 0.05% excise duty on all remittances of KSh 500,000 or more, transferred through banks and other financial institutions; as well as an increase in the excise duty charged on money transfer services by mobile phone providers from 10 percent to 12 percent, all geared to financing Universal Health Care – another Big 4 pillar.

Several of these proposals have been rightly criticised as being unjust and inordinately detrimental to low-income earners. With more than a third of all Kenyans living on less than Ksh 100 per day, a projected VAT-inclusive paraffin price of KSh 105 per litre is simply unreasonable. The curb on logging has already raised the cost of the popular-sized sack of Charcoal to more than Ksh 3,000 in parts of Nairobi, with the 4-kg tin costing more than KSh 150. With electricity prices also being ramped up as the monopoly power distributor Kenya Power struggles to maintain solvency following years of mismanagement, low and middle income earners are clearly big losers. The situation is no better for businesses, notably manufacturers and other high energy consumers. Early this month, the Kenya Association of Manufacturers registered strong objections to the revised energy tariffs which entailed a 36 percent increase in the energy base-cost – before the envisaged 16 percent VAT increase – which KAM argued would have a detrimental effect on the cost of doing business in the country.

With more than a third of all Kenyans living on less than Ksh 100 per day, a projected VAT-inclusive paraffin price of KSh 105 per litre is simply unreasonable. The curb on logging has already raised the cost of the popular-sized sack of Charcoal to more than Ksh 3,000 in parts of Nairobi, with the 4-kg tin costing more than KSh 150. With electricity prices also being ramped up as the monopoly power distributor Kenya Power struggles to maintain solvency following years of mismanagement, low and middle income earners are clearly big losers.

A recurring complaint from the private sector over the past half-decade has consistently been that consumer purchasing power has contracted considerably and that this is being exacerbated by recent and proposed tax measures. The decline in tax revenues despite the increases in tax rates, tax measures and collection efficiencies by KRA (notably year-on-year growth in taxpayers registered on KRA’s I-Tax platform), all but confirms a sharp drop in formal economic activity over the period.

Arthur Laffer who was an adviser to the Nixon/Ford Administration in the mid-1970’s mainstreamed the simple mathematical tautology that there is a point beyond which any increases in tax rates will always result in declining tax revenues. Laffer’s analysis of the US economy at the time recommended a decrease in federal tax rates to boost tax revenues. Rotich’s proposed tax measures risk the same results by further dampening of economic activity as well as greater tax evasion.

3. A Crowded-out Private Sector

The aforementioned slump in tax revenue growth was also partially influenced by the slowdown in bank profitability – which in turn was due to the twin influences of growing bad loans and reduced access to credit by the private sector. These factors are inexorably linked to diminished private sector performance. However, reduced access to credit by the private sector in Kenya is not a new phenomenon; nor are its fundamental causes. Its disruptive influences however, are significant. Commercial credit to the private sector has contracted from about 24 percent in 2013 to 18 percent by end of December 2015, to about 2.5 percent in June 2018. This is despite the implementation of interest caps in August 2016, disabusing the suggestion that enhanced credit to the private sector was the intended beneficiary of the interest rate caps. In contrast, during the same period annual growth in lending to government averaged 14%.

Table 7

Table 7

The Banking Amendment Act 2016 proposed by MP Jude Njomo was signed into law by President Uhuru Kenyatta with the same hollow promise of cheaper and more private sector lending by banks that a similar bill by then MP Joe Donde had made in the year 2000. The backgrounds shared notable similarities however – most notably heavy government borrowing. Domestic borrowing was indeed high in the late 1990s – evidenced by the 91-day Treasury Bill on offer with a 21% return in June 1999. By 2000, domestic borrowing was attracting Ksh 22 Billion in annual interest payments. The stock of domestic debt by June 2000 stood at KSh 164 Billion with new issues representing 17.5 percent of government revenue. By June 2007, with short term Treasury Bill rates down to less than 8 percent, the stock of domestic debt had only risen modestly to KSh 405 Billion representing 22.1 percent of GDP, and attracting interest payments of KSh 37 Billion in FY 2006/2007. By March 2016 however, the stock of domestic debt had jumped to KSh 1.65 Trillion representing close to 27 percent of GDP and was attracting a massive 30 percent of total government revenue in debt service. And that’s not even taking into account external debt which had grown at a similar rate. The stock of domestic debt in March 2018 had reached KSh 2.3 Trillion, attracting more than KSh 350 Billion in annual debt payments.

Arthur Laffer who was an adviser to the Nixon/Ford Administration in the mid-1970’s mainstreamed the simple mathematical tautology that there is a point beyond which any increases in tax rates will always result in declining tax revenues…Rotich’s proposed tax measures risk the same results by further dampening of economic activity as well as greater tax evasion.

In August 2000, Commercial bank lending rates averaged close to 21 percent and deposit rates about 7 percent, providing obvious justification for the Njomo Bill’s popular support. The stock of non-performing loans (NPLs) at the time, was an eye-popping KSh 122 Billion in April 2001, (40 percent of total lending). In June 2018 and despite interest rate caps in place, NPLs represent 12.4 percent of commercial lending with an estimated Ksh 303 Billion in this category.

Table 8

Table 8

The Parlous state of Kenya’s national accounts – most notably the KSh 5 Trillion stock of public debt and ballooning budget deficit – but also poor performance of the real economy with stagnant exports and tax revenues, suggests that the government cannot afford to be adding to the burden borne by the private sector. It also suggests that the slew of tax measures proposed in Budget 2018 was purely about desperately seeking to finance reckless government spending and not about providing incentives for private sector economic growth. Critically, it also confirms that the interest caps were always really about government access to cheaper domestic borrowing and not about promoting private sector economic activity, which the government appears to be doing its best to stifle.