All protocols observed. Distinguished ladies and gentlemen, you are gathered here today to discuss corruption. I can say without fear of contradiction that this a subject that this gathering is imminently qualified to discuss. In fact, it is conceivable that a gathering of people as knowledgeable as you are in matters of corruption is unprecedented in world history. The scions of crony capitalism are here. The lords of the land grabbing establishment are here. The dons of the tenderpreneur mafia are here. The money laundering fraternity— the lawyers, the accountants, the bankers, property moguls—you are all here.

My good friend and anti-corruption guru John Githongo has opined that we have, over the last two decades, assembled one of the most elaborate legal and institutional anti-corruption infrastructures in the world. It has made no difference at all. Corruption has continued to flourish. Nations renowned for honest government, such as the Scandinavian countries, are not distinguished by anti-corruption infrastructure. The normal accountability institutions —auditors, parliament, police and the courts—are sufficient. To borrow from computing, corruption is quite evidently not a hardware problem. It is the software that is corrupted.

The Oxford dictionary has four definitions of corruption, namely dishonest or fraudulent conduct by those in power; the process or effect of making someone or something morally depraved; the process by which a word or expression is changed from its original state to one regarded as erroneous or debased, and; the process by which a computer database becomes debased by alteration or the introduction of errors.

I suspect that in this convention your deliberations will be largely if not exclusively concerned with the first of these, namely, dishonest and fraudulent conduct, steering clear of election fraud, nepotism, debasement of the national honours system, corruption of harambee and much more. I need not dwell on the same since, as I have already observed, you are knowledgeable and experienced in those matters.

In this address, I will speak to the broader conception, namely to the process of alteration or debasement, or to borrow from the computer analogy, the corruption of software. I will do so by expounding on a theory of African politics due to Nigerian scholar Peter Ekeh known as the theory of the “two publics”. I will be quoting extensively from his paper Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa: A theoretical statement published in the 1975 issue of the journal Comparative Studies in Society and History.

Ekeh begins with the proposition that in western societies, the public and private spheres are governed by the same moral values and ethical norms: “what is considered morally wrong in the private realm is also considered morally wrong in the public realm [and] what is considered morally right in the private realm is also considered morally right in the public realm.”

He proceeds to postulate that in post-colonial Africa there are two public spheres. There is the conventional public sphere which he calls the “civic or state” sphere, and another which he calls the “primordial” sphere. He then postulates that the private and the primordial public spheres share a morality that does not extend to the state public sphere:

“When one moves across Western society to Africa, at least, one sees that the total extension of the Western conception of politics in terms of a monolithic public realm morally bound to the private realm can only be made at conceptual and theoretical peril. There is a private realm in Africa. But this private realm is differentially associated with the public realm in terms of morality. In fact there are two public realms in post-colonial Africa, with different types of moral linkages to the private realm. At one level is the public realm in which primordial groupings, ties, and sentiments influence and determine the individual’s public behavior. I shall call this the primordial public because it is closely identified with primordial groupings, sentiments, and activities, which nevertheless impinge on the public interest. The primordial public is moral and operates on the same moral imperatives as the private realm. On the other hand, there is a public realm which is historically associated with the colonial administration and which has become identified with popular politics in post-colonial Africa. It is based on civil structures: the military, the civil service, the police, etc. Its chief characteristic is that it has no moral linkages with the private realm. I shall call this the civic public. The civic public in Africa is amoral and lacks the generalized moral imperatives operative in the private realm and in the primordial public.”

In western societies, the public and private spheres are governed by the same moral values and ethical norms: “what is considered morally wrong in the private realm is also considered morally wrong in the public realm [and] what is considered morally right in the private realm is also considered morally right in the public realm.”

Allow me to illustrate. Every day Kenyans gather to organize weddings and funerals. They contribute money. They form committees, and appoint treasurers to keep the money. This money is seldom if ever stolen. We do not hear that a funeral or wedding did not take place because the treasurer took off with the money. Once the mission is accomplished a final meeting is convened to “break the committee.” The treasurer presents his or her report. If there is a surplus, it is donated to the bereaved or the couple as the case may be. If there are debts, the committee deliberates on how to settle them. There are no laws governing these undertakings. Increasingly, in urban settings, the activities are multiethnic thus we cannot say they are governed by tribal law. This is the primordial public—scrupulously honest and conscientious. This in the country with arguably the most corrupt states in the world. Same people.

You see, the state realm was a colonial imposition. It divided Africans broadly into those who resisted, and those who embraced it. Moral values do not apply in the sphere of oppression. The same applies to those who embraced it. Theirs was opportunism. They were motivated primarily by material gain. Both united in subverting it but for different reasons, as Ekeh explains:

“The African who evaded his tax was a hero; the African labourer who beat up his whjte employer was given extensive coverage in newspapers. In general, the African bourgeois class, in and out of politics, encouraged the common man to shirk his duties to the government or else to define them as burdens; in the same breath he was encouraged to demand his rights. Such strategy, one must repeat, was a necessary sabotage against alien personnel whom the African bourgeois class wanted to replace.”

The state realm was a colonial imposition. It divided Africans broadly into those who resisted, and those who embraced it. Moral values do not apply in the sphere of oppression. The same applies to those who embraced it. Theirs was opportunism. They were motivated primarily by material gain. Both united in subverting it but for different reasons…

Now that the African bourgeoisie has made an appearance, it is opportune to elaborate on it. A bourgeoisie is a capitalist class. In Europe, the bourgeoisie is the social class which emerged both as cause and consequence of the industrial revolution and capitalist development.

“In the course of colonization a new bourgeois class emerged in Africa composed of Africans who acquired Western education in the hands of the colonizers, and their missionary collaborators, and who accordingly were the most exposed to European colonial ideologies of all groups of Africans. Although native to Africa, the African bourgeois class depends on colonialism for its legitimacy. It accepts the principles implicit in colonialism but it rejects the foreign personnel that ruled Africa. It claims to be competent enough to rule, but it has no traditional legitimacy. In order to replace the colonizers and rule its own people it has invented a number of interest-begotten theories to justify that rule. I shall call the ideologies advanced by this new emergent bourgeois class in Africa the African bourgeois ideologies of legitimation.”

The bourgeoisie is associated with wealth creation and materialism.

The African bourgeoisie’s legitimising ideology is, I think, encapsulated by that ubiquitous political mantra “maendeleo.” Maendeleo is not development. Literary, maendeleo is to get rid of backwardness, to become modern. To drink busaa and chang’aa is not maendeleo. Beer and whisky is maendeleo. The maendeleo ideology is what Chinua Achebe characterizes as a “cargo cult mentality,” a “tendency among the ruling elite to live in a world of make-believe and unrealistic expectations”.

Ekeh has introduced another important concept that needs a remark or two, and this is the idea of legitimation. Legitimation is the process of making something morally acceptable to society. Legitimation is also about assuaging one’s conscience that there is a just cause behind unjust things. The legitimation of colonialism entailed presenting it as a civilizing mission, casting African ways as barbaric and backward, and Christianity and westernization as progress, bringing light to the heart of darkness. The African bourgeoisie’s predicament can be put as follows. It lacked the leadership credentials in the primordial public sphere—that belonged to the traditional rulers who colonialism had emasculated. Its power and comfort zone was in the state public—the amoral domain of oppression. How to square this circle?:

“Anti-colonialism did not in fact mean opposition to the perceived ideals and principles of Western institutions. On the contrary, a great deal of anti-colonialism was predicated on the manifest acceptance of these ideals and principles, accompanied by the insistence that conformity with them indicated a level of achievement that ought to earn the new educated Africans the right to the leadership of their country. Ultimately, the source of legitimacy for the new African leadership has become alien. Anti-colonialism was against alien colonial personnel but glaringly pro foreign ideals and principles.”

The African bourgeoisie’s legitimising ideology is, I think, encapsulated by that ubiquitous political mantra “maendeleo.” Maendeleo is not development. Literary, maendeleo is to get rid of backwardness, to become modern. To drink busaa and chang’aa is not maendeleo. Beer and whisky is maendeleo. The maendeleo ideology is what Chinua Achebe characterizes as a “cargo cult mentality,” a “tendency among the ruling elite to live in a world of make-believe and unrealistic expectations.”

Maendeleo ideology was and in many ways remains a fig leaf to cover the political nakedness of the African bourgeoisie, its inability to provide leadership on foundational questions of nation-building, among them how to transform the amoral state public sphere into an authentic values-based governance realm. To ask these questions was, still is, to become an enemy of maendeleo. To persist was, still is, to invite repercussions. There is perhaps no better specimen of the moral and intellectual crisis of the post-colonial African bourgeoisie than the ideological, political and economic incoherence of the (in)famous Sessional Paper No.10 of 1965 (African Socialism and its Application to Planning in Kenya).

Let us now consider the dialectics of the two publics. Dialectics simply means logic, or the process of reasoned inquiry. This will lead us directly into the subject of corruption.

On Friday you are hobnobbing with diplomats showing off your western sophistication, next day, you are being installed as a tribal elder adorned in monkey skins and porcupine quills Come Sunday, you are a suited picture of Christian piety buying indulgencies with money stolen from poor people. You are restless, troubled souls. This is what Ekeh means by psychic turbulence.

“Most educated Africans are citizens of two publics in the same society. The dialectical tensions and confrontations between these two publics constitute the uniqueness of modern African politics. A good citizen of the primordial public gives out and asks for nothing in return; a lucky citizen of the civic public gains from the civic public but enjoys escaping giving anything in return whenever he can. But such a lucky man would not be a good man were he to channel all his lucky gains to his private purse. He will only continue to be a good man if he channels part of the largesse from the civic public to the primordial public. That is the logic of the dialectics. The unwritten law of the dialectics is that it is legitimate to rob the civic public in order to strengthen the primordial public. (my emphasis)

Ekeh again:

“The native sector has become a primordial reservoir of moral obligations, a public entity which one works to preserve and benefit. The Westernized sector has become an amoral civic public from which one seeks to gain, if possible, in order to benefit the moral primordial public. Although the African gives materially as part of his duties to the primordial public, what he gains back is not material. He gains back intangible, immaterial benefits in the form of identity or psychological security. The pressure of modern life takes its toll in intangible ways. Behind the serenity and elegance of deportment that come with education and high office lie waves of psychic turbulence—not least of which are widespread and growing beliefs in supernatural magical powers. The primordial public is fed from this turbulence.”

I would like to believe that you recognize this description. Let me illustrate. On Friday you are hobnobbing with diplomats showing off your western sophistication, next day, you are being installed as a tribal elder adorned in monkey skins and porcupine quills Come Sunday, you are a suited picture of Christian piety buying indulgencies with money stolen from poor people. You are restless, troubled souls. This is what Ekeh means by psychic turbulence.

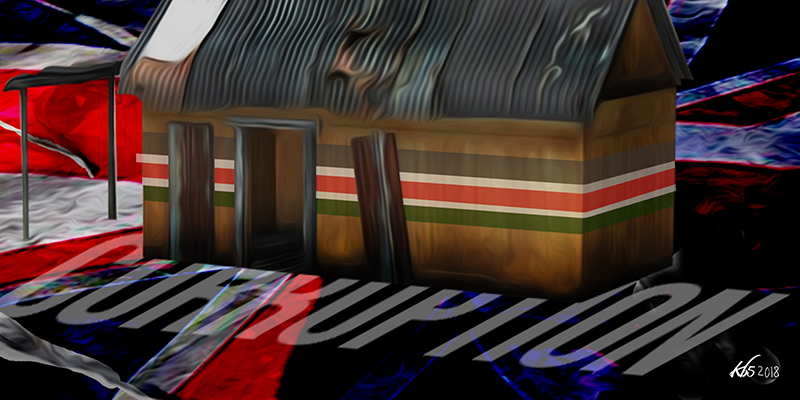

Corruption is a sine qua non of the post-colonial African State. You, ladies and gentlemen, are its handmaidens. Its unwritten law is that it is legitimate to rob the civic public in order to strengthen the primordial public. Until this law is repealed, so it will remain.

This then is the pathology of corruption. Corruption is a sine qua non of the post-colonial African State. You, ladies and gentlemen, are its handmaidens. Its unwritten law is that it is legitimate to rob the civic public in order to strengthen the primordial public. Until this law is repealed, so it will remain.