In September last year, the Tunisian parliament approved a law granting amnesty to officials accused of corruption during the rule of dictator Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali. This immediately triggered protests. Since the Arab Spring of 2011, Tunisia has been hailed as a democratic success in the Middle East. Unlike many of the other countries where the democratic convulsions of 2011 were quickly smothered or descended into chaos, Tunisia’s democratic experiment has perhaps not flourished but neither is in critical condition. In July 2013 Russia’s lower house of parliament approved an amnesty for thousands of entrepreneurs jailed for economic crimes. It was argued that the criminalisation of business disputes in Russia had had a deleterious effect on the commercial climate generally. In June 2015 the Indonesian Finance Minister Bambang Brodjonegoro announced an initiative aimed at boosting tax incomes by introducing an amnesty for past economic crimes that would allow billions of dollars parked abroad by Indonesians to be returned to the country. President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo’s government was in a crunch. They had embarked on a series of expensive infrastructure projects but needed to bump up tax revenues by 30 percent to fund them.

Amnesty programmes always imply pragmatic choices seen as disproportionately benefiting elites that have benefitted from corruption in the past. For the independent media and civil society, the concern is always one of entrenching impunity with regard to economic crimes. Where impunity attends to economic crimes it is always accompanied by similar official attitudes to sometimes the most egregious human rights abuses.

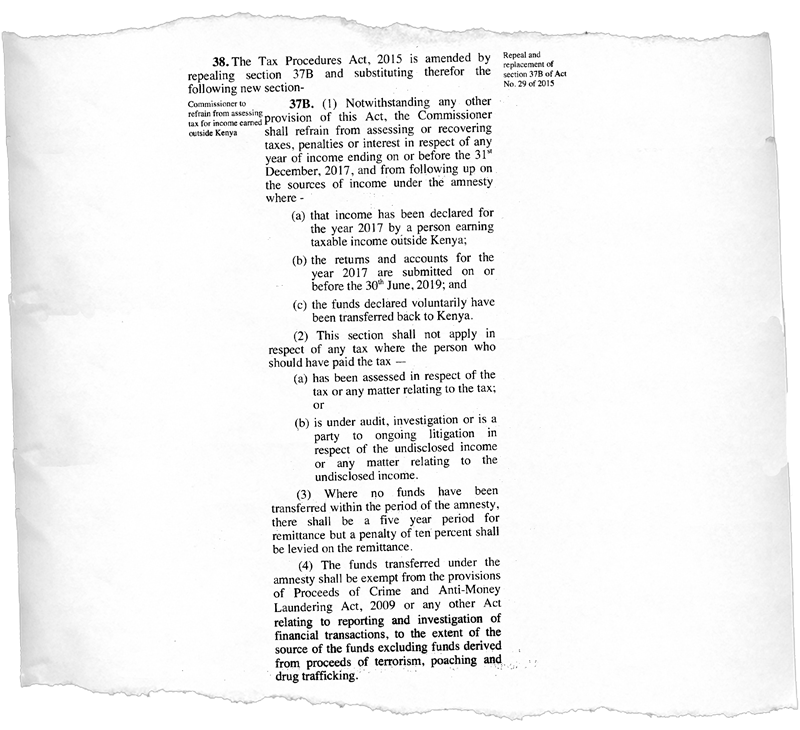

The Finance Bill, 2018 published with the budget last month, included an amendment to the Tax Procedures Act, 2015, suggesting that Kenya may have quietly chosen to go in a direction similar to Indonesia’s. Though the rationale of the action here has yet to be publicly articulated like similar initiatives in other parts of the world, the new amendment changes the tax amnesty that was declared three years ago. It has been expanded to include undeclared income to the extent that: “The funds transferred under the amnesty shall be exempt from the provisions of Proceeds of Crime and Anti-Money Laundering Act, 2009 or any other Act relating to reporting and investigation of financial transactions, to the extent of the source of the funds excluding funds derived from proceeds of terrorism, poaching and drug trafficking.”

Amnesty programmes always imply pragmatic choices seen as disproportionately benefiting elites that have benefited from corruption in the past. For the independent media and civil society the concern is always one of entrenching impunity with regard to economic crimes. Where impunity attends to economic crimes it is always accompanied by similar official attitudes to sometimes the most egregious human rights abuses.

Amnesty programmes always imply pragmatic choices seen as disproportionately benefiting elites that have benefited from corruption in the past. For the independent media and civil society the concern is always one of entrenching impunity with regard to economic crimes. Where impunity attends to economic crimes it is always accompanied by similar official attitudes to sometimes the most egregious human rights abuses.

The new amendment changes the tax amnesty that was declared three years ago. It has been expanded to include undeclared income to the extent that: “The funds transferred under the amnesty shall be exempt from the provisions of Proceeds of Crime and Anti-Money Laundering Act, 2009 or any other Act relating to reporting and investigation of financial transactions, to the extent of the source of the funds excluding funds derived from proceeds of terrorism, poaching and drug trafficking.

Money has no loyalty and in this globalised era, wears the uniform or label of no country. It doesn’t announce itself as in, “I am being laundered”; or, “This is terrorism finance or the proceeds of poaching.” The rigour and integrity of the oversight mechanisms meant to check these flows needs to be world class. And even world class anti-money laundering mechanisms in the world’s most developed economies with the best resourced investigative authorities have only made a small dent on the giant global flows of illicit wealth around the globe over the last two decades. Typically, drug dealers, money launderers and globalised criminal enterprises are better resourced and more ruthlessly managed than even the best policing institutions in the world.

Kenya’s recent changes, combined with currently advanced plans to turn Kenya into an international finance center – a tax haven, essentially – could herald the end of the war against corruption in Kenya as we know it. All while we are distracted by the exciting scandals being reported on in the media. The reality of what’s playing out remains to be seen but it should be of some concern that one of the most corrupt yet sophisticated financial sectors in Sub-Saharan Africa is about to open itself up in a structured legalised manner to the darkest element of the global financial system.

Kenya’s dalliance with amnesties for past economic crimes is not new. As the end of the Moi era drew closer, I was involved in a national debate regarding what we would do with past economic crimes when a new administration came to power after the December 2002 elections. In 2000 and 2001, Transparency International-Kenya, the National Council of Churches of Kenya and the Law Society of Kenya among others convened a series of debates on the subject. The rationale at the time was that, first Kenya’s public service culture had been ruined by rampant theft and plunder especially since the 1972 Ndegwa Commission Report which legalised conflict of interest. Changing this culture meant having a structured national approach to dealing with past corruption. An option was to articulate an amnesty mechanism accompanied by a restitution programme that would allow the return of corruptly acquired wealth and a lustration initiative that would forever bar those who were granted the amnesty from ever holding public office in Kenya. The Commission of Inquiry into the Illegal and Irregular Allocation of Public Land of 2003 (aka the Ndung’u Commission) came out of this thinking, as did efforts to trace wealth stashed illegally overseas by Kenyans.

A second strand of reasoning at the time was that the opposition, which seemed likely to win the election, would be coming into office broke after over a decade of expensive campaigning, and would be confronted by a Moi-era political and bureaucratic elite opposed to progressive reform and possessed of the kind of wealth to cause a huge amount of political trouble; indeed with the capacity to stymie real reform altogether. The thinking was that this wealth needed to be squeezed out of our politics to allow a new administration the space to implement far reaching reforms aimed at improving the welfare of Kenyans generally and transforming the economy, society and politics.

The Kibaki era initiative faltered when the elite around him led by some of his key ministers decided to make private deals with the very thieves their own administration was ostensibly chasing down. It got so bad at one point that some officials were using the anti-corruption campaign as a highly lucrative extortion tool. Well-heeled players from the past coughed up the equivalent of billions of shillings in cash, forex, land, real estate, company shares and other considerations in exchange for essentially bringing the anti-corruption campaign to a halt and turning it into a PR gimmick to placate wananchi.

When one looks around the world since the early 1990s, amnesty initiatives for economic crimes – especially in countries where corruption is systemic – have largely been failures. They succeed in facilitating the repatriation of some hot money that causes bumps in stock markets, hikes real estate prices and strengthens local currencies in the short term. In the medium term they seem to send a message that theft works and therefore serve to entrench impunity especially with regard to economic crimes. In the developing world their limited successes seem to apply only during the first 18 months of a popular regime elected on an anti-corruption ticket.

The Kibaki era corruption amnesty initiative faltered when the elite around him led by some of his key ministers decided to make private deals with the very thieves their own administration was ostensibly chasing down… At one point, some officials were using the anti-corruption campaign as a highly lucrative extortion tool. Well-heeled players from the past coughed up billions of shillings in cash, forex, land, real estate, company shares and other considerations in exchange for essentially bringing the anti-corruption campaign to a halt and turning it into a PR gimmick to placate wananchi.

It is also the case that typically these amnesty initiatives are implemented only in the most corrupt countries where the context makes for the greatest challenges. This, as I have noted earlier, doesn’t always apply when accompanied by tectonic political changes, notably as the ones we are witnessing in Malaysia today.

Additionally, it is often the case that amnesty programmes are often desperate measures aimed at dealing with the fiscal distress of corrupt regimes. In this sense they can also be deeply cynical ploys to launder the ill-gotten gains of the past and concurrently wave the white flag for a political elite that has given up the fight against systemic corruption in public life.

As I observed above, as an instrument aimed at dealing with a widespread culture of theft and plunder the issue of an amnesty for economic crimes has bubbled up several times over the last two-decades in Kenya. In 2007 the KACC complained about amendments the legislature had introduced to the Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act, 2003 following the Anglo Leasing scandal. In a statement issued in September 2007 the then head of the Commission, Justice Aaron Ringera argued that parliament had essentially granted ‘a blanket amnesty’ for economic crimes committed before the 2nd of May 2003. More recently, the NCCK’s leadership, confronted with the current explosion of corruption scandals in the media called for a one-year amnesty for past corruption after which all future graft would be punished ruthlessly. The NCCK has been one of the most consistent actors in this debate for almost two decades now. The former head of the Anglican Church, Archbishop Wabukala is chair of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission and was party to the statement made by the NCCK in May.

In 2007 the KACC complained about amendments the legislature had introduced to the Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act, 2003 following the Anglo Leasing scandal. In a statement issued in September 2007 the then head of the Commission, Justice Aaron Ringera argued that parliament had essentially granted ‘a blanket amnesty’ for economic crimes committed before the 2nd of May 2003. More recently, the NCCK’s leadership, confronted with the current explosion of corruption scandals in the media called for a one-year amnesty for past corruption after which all future graft would be punished ruthlessly.

The amendments to the Tax Procedures Act 2015 may indicate that the Jubilee regime appears to have cynically heeded the NCCK’s call. Either that or the extent of the regime’s fiscal distress as it implements an IMF sanctioned austerity programme is such that they have resorted to extraordinary measures to find the money to keep government going and the elite with their snouts in the trough. I argued last month that in Kenya, the real corruption is not in the scandals that are tantalising us in the media but in the budget.

(Research by Juliet A. Atellah)