I remember in the 1980s having a great time with friends who were then living at the University of Nairobi halls of residence. A favourite stop-over for drinks was the Serena Hotel. This was the case at least until the price of beer was decontrolled in early 1993. Beer prices shot up and students were forced to humbler watering holes downtown. The Serena proceeded with a decade-long makeover that’s transformed it into today’s five star, increasingly al Shabaab-proof, world class hotel; and captains of industry and tenderprenuers never again had to share the urinals in the evening with opinionated and inebriated first year university students.

The process of decontrolling prices, generally liberalising the economy and politics accelerated exponentially after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Successive Kenyan regimes have never been big on the social cost of their policies, but even Moi – with his finger ever on the political pulse of the nation – repeatedly balked when pushed by the World Bank and IMF to liberalise the economy through the 1980s. He was especially wedded to the inefficient parastatals that were highly effective political patronage machines. Indeed, it is ironic that in the 21st century, the National Youth Service, National Cereals and Produce Board, Kenya Power and Lighting Company, Kenya Pipeline Company, Uchumi Supermarkets and other such entities have assumed this mirro-role under the very noses of us Kenyans, and the very same Bretton Woods agencies that pushed for ‘reforms’ through the 1980s and 1990s.

I refer to the decontrol we experienced in the 1990s because it transformed Kenya’s sense of its own political and economic sovereignty. In 2003 when NARC came to power, economic advisors joked that officials at the Ministry of Finance were often bleary-eyed because they only went to sleep after they had checked in with the IMF in Washington. By 2008 Kenya had largely been weaned off its dependence on the architects of the Washington Consensus. It helped that China had dramatically raised its commercial profile on the continent in ways that elites could use to their economic and political advantage.

With this in mind and in hindsight, March was a most interesting month for Kenya. Indeed in just one week a series of events combined to affirm a significant reversal in Kenya’s economic sovereignty with far-reaching implications for our politics.

On the 6th of March, the Minister of Finance, Henry Rotich, made the surprise announcement that the government was ‘broke’. He would deny this a day later in rather incongruous fashion. On the same day he and the Central Bank Governor Patrick Njoroge essentially signed on to an IMF austerity programme.

It wasn’t the traditional IMF programme circa 1980/90s, but it nevertheless was an acknowledgment that we were complying with a range of ‘confidence building’ measures ‘agreed’ with the IMF as we renegotiated our expired precautionary facility with them. For a country like Kenya that has exposed itself to the winds of the international markets to underwrite an ongoing forex-denominated borrowing binge, the IMF’s confidence serves as an insurance to Wall Street that we can, for example, still make our upcoming Eurobond interest payments.

We find ourselves in a conditionality-straitjacket similar to Moi’s in the 1990s. This one may be more politely worded, but the conditions are just as lethal: to secure a six-month extension of the US$ 1.5 billion IMF Stand-by Arrangement, the Fund was demanding that Treasury “[reduces] its fiscal deficit and substantially modify interest controls’. The SBA was due to expire on March 13. Treasury was asking for what was in effect a last-ditch six month extension, to September 2018.

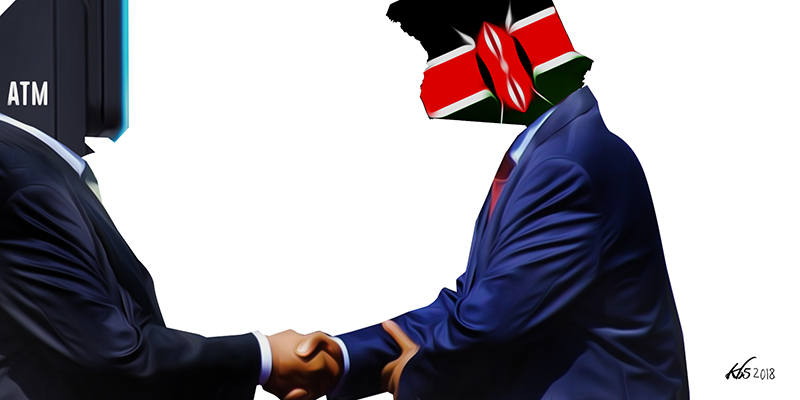

It is thus that the next day, March 7th, the IMF made its ‘end of mission’ pronouncement in Kenya’s regard. Two days later, on the 9th of March, Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga stepped out of Harambee House to their now famous ‘handshake’ that has temporarily reordered our politics. Coincidentally the American Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, was visiting Kenya (and being sacked by President Trump at the same time). I should like to speculate that these events are related.

We find ourselves in a conditionality-straitjacket similar to Moi’s in the 1990s. This one may be more politely worded, but the conditions are just as lethal: to secure a six-month extension of the US$ 1.5 billion IMF Stand-by Arrangement, the Fund was demanding that Treasury “[reduces] its fiscal deficit and substantially modify interest controls’. The SBA was due to expire on March 13. Treasury was asking for what was in effect a last-ditch six month extension, to September 2018.

*****

In November 1991, speaking at a donor consultative meeting in Paris, Kenya’s Finance Minister, the late Professor George Saitoti, announced that the KANU regime had agreed to repeal Section 2A of the constitution and allow the reintroduction of political pluralism. Still, the donors imposed an aid freeze on Kenya primarily as a result of the failure of a pre-agreed economic ‘stabilisation’ programme.

In the years up to 1993 Kenya received over US$1 billion per annum in donor aid – most of it at concessionary rates from Western donors. Indeed, in 1989/90 Kenya received US$1.6 billion from them. And the year before in 1988, KANU had scrapped the secret ballot, holding elections where voters queued behind their candidates. So this aid wasn’t linked to our deteriorating politics then. As a result, the aid freeze of 1991 was not only economically traumatic, the trauma was also political. At the time our understanding was that Moi had caved into intense domestic and international pressure for political and economic liberalisation. That Saitoti chose to make the all-important announcement while facing donors, however, was itself significant. Some insiders at the World Bank at the time insist that Moi misread the moment. The World Bank and IMF had primarily been pressuring Kenya on the economic reform front. It was the bilaterals who had suddenly become more eager about progressive political change.

Indeed, from the mid-1980s the regime had agreed to liberalise the economy which meant doing away with a range of parastatals (that at one point employed over 50 percent of civil servants); and the removal of foreign exchange and price controls, among a raft of other measures.

Initially the government acquiesced to the demands on the understanding that they would be implemented gradually. This was articulated in Sessional Paper No.1 of 1986. The subtext of the reforms would lead to the dismantling of President Moi patronage machine – it was, essentially, political suicide. So he dragged his feet. But then the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. Moi’s backers in the West, the US and UK in particular quickly started speaking a new language. Ambassadors who had never publicly agitated for transparency, human rights, good governance, accountability – the buzz-words of this new dispensation – when Kenya was a ‘pro-Western anti-communist bastion on the Eastern side of Africa’ suddenly changed their tune. President Moi criss-crossed Kenya complaining about this betrayal and warning that multipartyism in Kenya’s tribal context would lead to division and violence.

Faced with an aid freeze and under enormous pressure to liberalise both the economy and politics, Moi’s grudging acceptance of both was accompanied with his signing off on the Goldenberg scheme that promised to avail the much needed foreign exchange necessary to keep things going through the crunch and finance the 1992 multi-party elections. Thus the Goldenberg scandal was born. The people who walked Goldenberg into State House were the country’s long-serving spy chief, James Kanyotu, and his co-director in Goldenberg International Ltd, Kamlesh Pattni, a 27-year old small-time jeweller. The latter had been trying to flog the scheme to mandarins for some time without success. Now it was eagerly snapped up and transformed into the single most intense conflagration of political corruption in the country’s history.

Kenya saw 10 percent of GDP (US$1 billion at the time) extracted by the Goldenberg scams. The late Kanyotu had saved Moi’s bacon a couple of times before, notably in 1982 when he rushed to the Nyeri Agricultural Show on Friday July 30th to warn the President that Air Force officers were planning a coup and seeking permission to arrest them. Moi refused and the coup attempt took place that Sunday 1st August 1982. Moi in 1991, presented with a solution, did not hesitate to take it.

The people who walked Goldenberg into State House were the country’s long-serving spy chief, James Kanyotu, and his co-director in Goldenberg International Ltd, Kamlesh Pattni, a 27-year old small-time jeweller. The latter had been trying to flog the scheme to mandarins for some time without success. Now it was eagerly snapped up and transformed into the single most intense conflagration of political corruption in the country’s history.

*****

Kenya came out of a failed election process last year with a regime devoid of legitimacy; an economy steeped in debt and hobbled by a wild cycle of looting; an emboldened opposition speaking for almost 70 percent of the country and resolutely implementing a political programme Jubilee couldn’t respond to without a campaign of violence that threatened to burn the entire house down.

For Uhuru Kenyatta, the start of 2018 presented an almost insurmountable set of challenges: implementing an austerity programme while having to deal with a focused opposition breathing down his neck. But he had one thing Moi didn’t have in 1991: the support of both the West and the Bretton Woods institutions. As sub-Saharan Africa teeters on the brink of another debt crisis, the IMF has been generally silent, as even status-quo Western development economists are beginning to question the wisdom and sustainability of the debt binge numerous developing countries have embarked on over the past decade. Here in Kenya David Ndii has been flagging the issue for six years non-stop.

It is probably pure coincidence that the March 9th ‘handshake’ between Raila Odinga and Uhuru Kenyatta that relieved so much political pressure from the Jubilee regime came at a moment when Kenyatta needed all the economic wriggle room that the crisis could allow. But just as in Moi’s case in 1991, the handshake deal was fronted, not by the usual political or bureaucratic types, but by the men from the shadows who give advice on matters of national security and preservation of the regime. Indeed, the politicos and bureaucrats were largely cut out of the handshake arrangement. On every side many seemed as surprised by it as most Kenyans. Add to this the fact that the appointed interlocutors are Mr. Odinga’s lawyer, Paul Mwangi, and Dr. Martin Kimani, the head of counter terrorism.

It is probably pure coincidence that the March 9th ‘handshake’ between Raila Odinga and Uhuru Kenyatta that relieved so much political pressure from the Jubilee regime came at a moment when Kenyatta needed all the economic wriggle room that the crisis could allow. But just as in Moi’s case in 1991, the handshake deal was fronted, not by the usual political or bureaucratic types, but by the men from the shadows who give advice on matters of national security and preservation of the regime.

I have argued before that Kenya’s elite has often been most amenable to giving up political ground when they are in a fiscal bind. Considered together the political and economic events of March are interesting in their similarities, no matter how apparently tenuous, to the situation in 1991 when Moi reached out to his friend and spy chief (who retired that same year), to sort out the mess of having to win a multi-party election at any cost and finding the resources to do it in the middle of an aid freeze. Kenyatta is attempting to manage his own succession with the economy in a mess; the politics polarised but opposition demobilised for now; and, in the midst of a looting spree that makes Goldenberg look like a minor hold-up in a corner shop. Behind it all one cannot help that feeling that, as they say, ‘we just got owned!’ Literally in our case as Kenyans.

(Research by Juliet A. Atellah)