Those of us who lived through the structural adjustment era would never have thought that we would live to see another IMF Letter of Intent. But then again, we would never have expected to see NYS buses ferrying commuters in Nairobi either.

But what is a Letter of Intent? It is an ominous missive ostensibly written to the IMF Managing Director by governments seeking an IMF bailout. It is usually co-signed by the Minister of Finance and the Central Bank Governor, outlining the austerity measures that the said government intends to take to fix its finances. In my day, it used to be addressed “Dear Mr. Camdessus”. These days, it is addressed “Dear Ms. Lagarde”. Only, it is not written by the government. It is drafted by the IMF staff and presented more or less as a fait accompli for signature. Henry Rotich and Patrick Njoroge signed one recently, dated March 6 2018. Here are some excerpts:

“The introduction of interest rate control in September 2016, which were aimed at addressing the high cost of credit, has had unintended adverse consequences on credit growth and monetary policy effectiveness.”

“In making this request, we commit to strong policies to achieve our program objectives. These include: (1) a reduction in the fiscal deficit from 8.8 percent of GDP in 2016/17 to 7.2 percent GDP by the end of this fiscal year (June 30, 2018) and a further reduction to 5.7 percent of during the next fiscal year (June 30, 2019); (2) a significant modification of interest rate controls to avoid their adverse impact on credit to the private sector, monetary policy effectiveness, and financial stability; and (3) strengthening the monetary policy framework, including the introduction of an interest rate corridor following the significant modification of interest rate controls.”

What caused credit to collapse? Interest rates did not go up suddenly. The average lending rate leading up to the sudden nosedive in bank lending was stable, fluctuating around 16 percent. The rate inched up two percentage points where it remained until the cap was imposed a year later. The cause of the credit slump lies elsewhere.

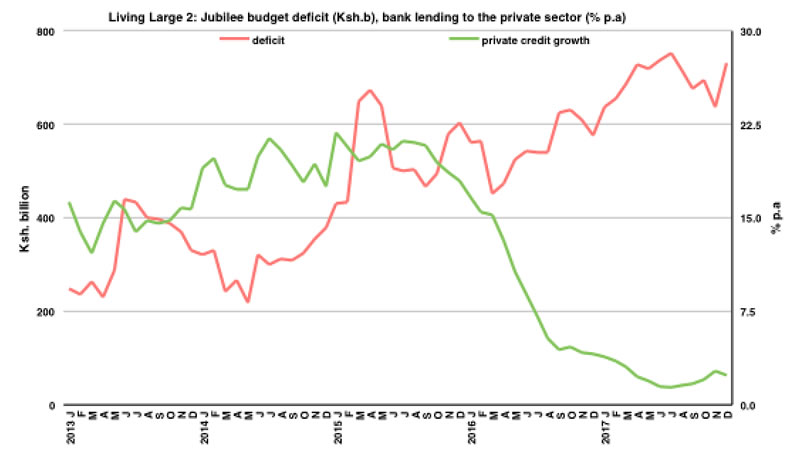

This columnist, along with other experts, argued strongly against the interest rate caps, as did the Central Bank. That said, the claim that interest rate controls had adversely affected credit is incorrect. The interest rate cap was introduced in August 2016. By then, bank lending to the private sector had been in free-fall for a year, plummeting from 20 percent growth per year to five percent per year. The interest rate caps do not appear to have made much of a difference either way.

What caused credit to collapse? Interest rates did not go up suddenly. The average lending rate leading up to the sudden nosedive in bank lending was stable, fluctuating around 16 percent. The rate inched up two percentage points where it remained until the cap was imposed a year later.

The cause of the credit slump lies elsewhere.

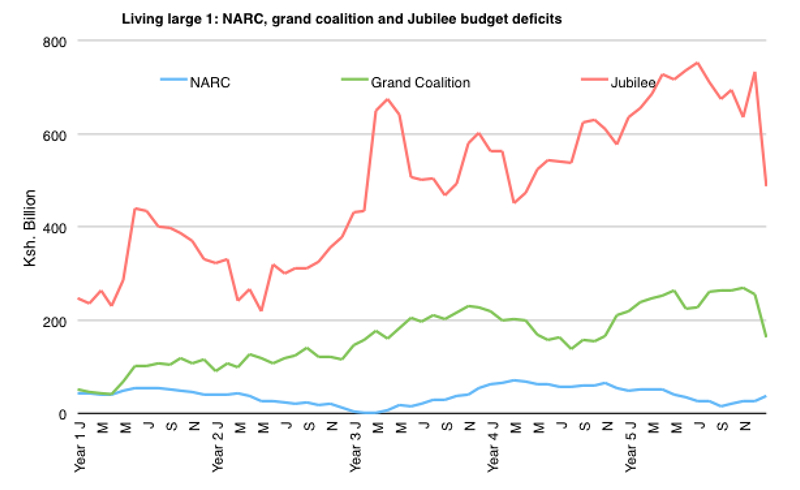

The Jubilee administration’s profligate ways are now the stuff of legend. Still, seeing is believing (See chart 1, below). To wit, Jubilee assumes office with the annual budget deficit running at Ksh. 200 billion, just under six percent of GDP. It surges in its first three months and then slows back down to the Ksh. 200 billion level in the first quarter of 2014, equivalent to four percent of GDP. This initial surge can be attributed to the roll-out of devolution. The respite was temporary. Over the next year, the deficit surges threefold, hitting Ksh. 670 billion, a mind-boggling 12 percent of GDP. It slows down thereafter but not by much. The next surge, from the beginning of 2016, takes it up to Ksh. 750 billion, equivalent to 10 percent of GDP at the end of the term.

In comparison, NARC maintained a budget deficit of 2.5 percent of GDP, rising to 5.3 percent under the grand coalition, and to 8 percent under Jubilee. It is noteworthy that Uhuru Kenyatta was the grand coalition’s finance minister. Eight percent of GDP may not sound like a whole lot, until you consider that Government revenue is in the order of 18 percent of GDP, hence an eight percent of GDP budget deficit is in fact equivalent to government spending 44 percent more than its income year after year. A 2.5 percent budget deficit is sound, five percent is alarming, eight percent is downright irresponsible.

In comparison, NARC maintained a budget deficit of 2.5 percent of GDP, rising to 5.3 percent under the grand coalition, and to 8 percent under Jubilee. It is noteworthy that Uhuru Kenyatta was the grand coalition’s finance minister. Eight percent of GDP may not sound like a whole lot, until you consider that Government revenue is in the order of 18 percent of GDP, hence an eight percent of GDP budget deficit is in fact equivalent to government spending 44 percent more than its income year after year. A 2.5 percent budget deficit is sound, five percent is alarming, eight percent is downright irresponsible.

When the government goes on a spending spree, it distorts incentives. The NYS and health ministry scandals were only the most egregious exposés of what goes on in public procurement. Opportunities such as selling mobile clinics that can be bought on Alibaba for US$ 3000 (Ksh. 300,000) to the government at Ksh. 8 million can be counted on to divert a lot of resources, human and financial, to the tenderpreneurs.

Deficit spending of this magnitude has economic consequences of many kinds, none of them good. First, the deficit has to be financed. It can be financed by borrowing externally, or domestically. Despite the Chinese loans for the SGR railway, the Eurobond and several other syndicated foreign bank loans, half the deficit has been financed by domestic borrowing. The effect is that the government crowds out private lending. The impact is immediate. As soon as the government publishes a budget with a huge domestic borrowing requirement, lenders and institutional investors know that they will be able to lend more and extract higher yields from the government. They begin to adjust their portfolios accordingly.

And that’s exactly what we see (See chart 2, below). Jubilee’s spending spree binge was announced with the budget read in June 2014. Deficit spending surges threefold from Ksh. 220 billion in the year to May 2014 to peak at Ksh. 670 billion for the year to April 2015. It takes a while for the madness to work its way through the economy. Six months later, bank lending to the private sector goes into free fall. By the time interest rates are capped a year later, private bank lending has slowed to five percent per year, down from 20 percent. Capping did not help. A year later, lending was down to 1.5 percent. By this time the deficit was running at Ksh. 750 billion, equivalent to 60 percent of government revenue.

With market interest rates, this kind of binge spending would have pushed up government borrowing rates to the mid-20s, with attendant financial and political consequences. Unwittingly, the interest rate cappers, whose stated objective was to borrow cheap, ended up shielding the government from the consequences of its recklessness, with no benefit to themselves.

With market interest rates, this kind of binge spending would have pushed up government borrowing rates to the mid-20s, with attendant financial and political consequences. Unwittingly, the interest rate cappers, whose stated objective was to borrow cheap, ended up shielding the government from the consequences of its recklessness, with no benefit to themselves.

Second, when the government goes on a spending spree, it distorts incentives. Governments are generally wasteful spenders, corrupted ones even more so. The NYS and health ministry scandals were only the most egregious exposés of what goes on in public procurement. Opportunities such as selling container clinics that can be bought on Alibaba for US$ 3000 (Ksh. 300,000) to the government at Ksh. 8 million can be counted on to divert a lot of resources, human and financial, to tenderpreneurship.

Third, government spending sprees inflate costs, as businesses are forced to compete with the inflated prices that service providers are able to charge the government. Even availability of some services becomes a problem as providers chase lucrative government contracts.

Now comes the conundrum. To cut the deficit, the government has to raise more revenue and cut expenditure. Both of these are contractionary. The government will be seeking to extract more revenue from a private sector that it has done all it could to weaken. And economic growth is now heavily dependent on the very government spending that needs to be cut.

Fourth, governments make bad investments. If a private enterprise makes a few bad investments, it goes bust. Government that make bad investments are re-elected. This I need not belabor, but I will. The flagship standard gauge railway, apparently so desperately needed, is turning out to be the boondoggle that its critics, this columnist included, said it would be. We have a 40 percent electricity generation capacity surplus. Investors are not flocking, but consumers are up in arms. There are others: Galana-Kulalu irrigation project, the failed groundnut scheme. The said container clinics, which cost Ksh. 800 million, are rusting away in Mombasa. Makueni Governor Kivutha Kibwana’s fruit processing factory is reported to have cost Ksh. 450 million.

The morning after Jubilee’s spending jamboree is aptly summed up in the World’s Bank’s latest Kenya Economic Update report, published earlier this week (it is worth noting that the World Bank has been one of the cheerleaders of the Jubilee administration’s debt fueled infrastructure binge):

“Worryingly, the contribution to growth from private investment has been decelerating in recent years. Unlike the solid contribution to growth from the public sector, the contribution from private investment has been negative in recent years, declining from 1.3 percentage points of GDP in the four years leading to 2013 to negative 0.7 percentage points in the four years leading to 2017, a swing of 2 percentage points of GDP.”

Growth in the four years to 2013 averaged 6.1 percent, meaning that private investment contributed 20 percent of it. Growth in the four years to 2017 was 5.4 percent meaning that it would have been 6.1 percent if private sector investment had not collapsed.

Now comes the conundrum. To cut the deficit, the government has to raise more revenue and cut expenditure. Both of these are contractionary. The government will be seeking to extract more revenue from a private sector that it has done all it could to weaken. And economic growth is now heavily dependent on the very government spending that needs to be cut. The two year 3.1 percentage point adjustment (from 8.8 to 5.7 percent of GDP) is in the order of Ksh. 270 billion. Given the state of the economy, revenue will contribute very little of this. Expenditure will have to do most of the adjusting – and that requires resolve and reforms the discipline for which Jubilee will struggle to muster.

The principal on market debt can be rolled over, but interest is paid out of revenue – Ksh. 284 billion this year. But the amount of debt that we now have to refinance leaves very little headroom to borrow for new projects. The prospectus for the US$ 2 billion second eurobond raised two months ago said it was for investment and “liability management.” Make that all of it. Big four agenda, anyone?

As we demonstrated a fortnight ago, most of the borrowed money has been plundered or squandered. There are no economic returns expected from the investments. But the debts have to be serviced. As noted, the IMF standby credit facility commits the government to review the interest rate cap. The choice of language reflects a recognition that repealing the law may be a tall order. But make no mistake about it: whatever manouvering they have made to have it implemented, will be to the same effect. A one percentage point interest cost increase on the Ksh. 2.3 trillion domestic debt translates to Ksh. 23 billion.

The principal on market debt (i.e. treasury bills, bonds and Eurobonds) can be rolled over but interest is paid out of revenue – Ksh. 284 billion this year. But the amount of debt that we now have to refinance leaves very little headroom to borrow for new projects. The prospectus for the US$ 2 billion second Eurobond raised two months ago said it was for investment and “liability management.” Make that all of it. Big four agenda, anyone?

It is fair to say that Uhuruto’s great leap forward has come a cropper. That though, was never in doubt.