Within two hours of Raila Odinga posting Good Friday greetings on his Facebook page, 6,000 people had told him exactly what they thought of him.

“The handshake should have happened today to rhyme with Judas [Iscariot]’s actions,” posted George Kingola, summing up the thinking of many.

Until Raila’s unsuccessful attempt this week to intervene in the Miguna Miguna deportation saga, even his fiercest critics had been bemused by his secretly organised ceasefire with Uhuru Kenyatta – the March 9, 2018 ‘handshake’.

Nothing had been settled since the August 2017 elections. In the bitter aftermath of it – the longest crisis in independent Kenya’s political history – the economy had ground to a halt. Perhaps more critically, a breakdown in ethnic relations had virtually unravelled whatever was left of Kenyan nationhood. And after Raila was sworn in as the People’s President on January 30, there was the very real sense that there now existed two parallel republics.

Miguna Miguna, who had commissioned the January 30 oath, had borne the brunt of the other State’s wrath. He was seized by police, detained without charge, and ultimately ‘deported’ to Canada, where he is a naturalised citizen, a deliberate and state-orchestrated defiance of numerous court orders.

Nothing had been settled since the August 2017 elections. …The economy had ground to a halt. Perhaps more critically, a breakdown in ethnic relations had virtually unravelled whatever was left of Kenyan nationhood. And after Raila was sworn in as the People’s President on January 30, there was the very real sense that there now existed two parallel republics

Raila has long enjoyed a cult following among his supporters as much for his political chutzpah as for his personal sacrifices against a dictatorship whose unbroken rein stretches back to the independence deal in Lancaster House. Thrice detained without trial and thrice denied electoral victory in the presidency by blatant vote rigging, he has become the poster politician for the African struggle against the deep state, inspiring long-drawn struggles in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Uganda and elsewhere. His personal suffering and sacrifices have created of Raila an institution of public trust. But Raila the dissident and Raila, the politician who entered the rough-and-tumble of Kenyan deal politics are two very different animals. Perhaps no country in Africa has witnessed the kind of deal politics that has played out in Kenya since the restoration of multiparty politics. Organised purely for the preservation of a political elite, the revolving-door defections of politicians, the disbandment and creation of new political parties, mergers, coalitions and marriages of convenience are all fuelled by cash and held together by an ever-changing ethnic pragmatism designed purely to preserve the beneficiaries of the Lancaster House independence deal and their sons and daughters, political and biological. It is this dexterity and lack of any guiding principles (except those of the stomach), that has allowed the tumbocracy to flourish.

Leveraging his struggle credentials to cast himself in the mould of South African freedom icon Nelson Mandela, Raila became a consummate pragmatist on this endless landscape of compromises, reaching out to erstwhile political rivals in a series of in bold moves, each one that changed politics – and the fortunes of rival politicians – in Kenya.

Raila’s March 9 detente with Uhuru Kenyatta can only be rivalled in its audacity by his National Development Party-KANU marriage with former president Daniel arap Moi two decades ago. Without so much as a by-your-leave to his opposition colleagues, Raila did the unthinkable, making a deal with Moi, the man who had signed his detention orders and consigned his father to house arrest. His rationale for this shotgun marriage was to use it as the Trojan Horse that would midwife a new constitution, and ultimately break KANU’s stranglehold on power. By the time Moi left power at the end of 2002, KANU was in ruins. But Raila had given Moi a lifeline; at Uhuru Park on the day he formally handed over power to Mwai Kibaki, he may have still been reviled but at least, he was tolerated, and was never prosecuted for any of the abuses committed during his tenure.

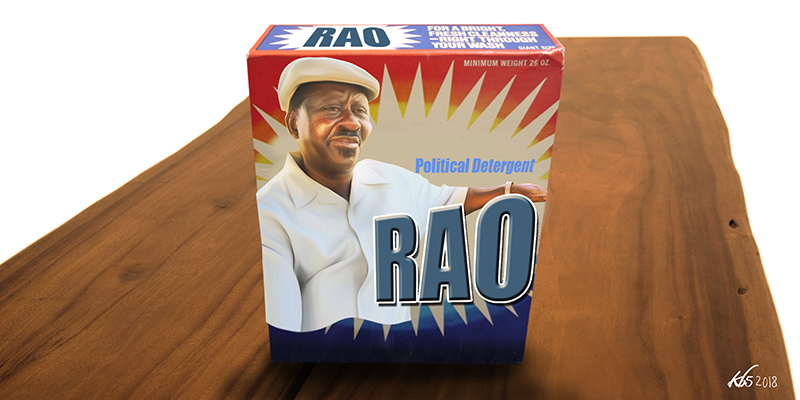

When Raila stood at the front steps of Harambee House for his handshake with Uhuru, he appeared to have embarked on his biggest political laundering project so far. The Jubilee administration had emerged from the 2017 election shorn of any real political legitimacy.

Raila has long enjoyed a cult following among his supporters as much for his political chutzpah as for his personal sacrifices against a dictatorship whose unbroken rein stretches back to the independence deal in Lancaster House. Thrice detained without trial and thrice denied electoral victory in the presidency by blatant vote rigging, he has become the poster politician for the African struggle against the deep state, inspiring long-drawn struggles in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Uganda and elsewhere.

It is now a distinct possibility that Uhuru Kenyatta will get away with all the crimes committed in his name in 2017’s long and violent post-election aftermath.

While Raila remains the father of the political deal, he knows he is running out of time and perhaps, out of the genius for a believable public spectacle. Compared to the February 2008 internationally brokered deal between Raila and then President Mwai Kibaki, Raila’s latest deal with Uhuru Kenyatta is long on prose and vague on detail. Despite the deaths of 448 Kenyans in police hands during the post-election violence in 2008, and an estimated Sh10 billion in economic losses, the Kibaki-Raila handshake seemed determined to deliver reforms and it will be remembered for the passage of a new Constitution of Kenya, 2010, as a well as an ambitious delivery programme.

Miguna Miguna was always going to upset the delicate balance of private deals. His second ‘deportation’ now calls Raila’s credibility into question with his base, who fear that he has exploited their sacrifices for personal gain, and openly accuse him of profiting from the blood of the dead.

“This Easter, visit Eva Musando,” posts Mwalimu Ongeti. “She is crying, shedding tears. Eva needs your help. She needs your handshake. Go empower Eva Musando and God of Israel will bless you abundantly.” Eva Musando, widow of Chris Musando, the electoral commission’s information communication manager murdered days to the August 8, 2017 election. Rights groups have estimated that over 60 people were killed in confrontations with police during protests over the elections.

Suspicions that Raila might have brokered a deal that is personally beneficial to him has damaged his standing as the leader of an opposition movement that has delivered the greatest results on the continent over two decades.

Leveraging his struggle credentials to cast himself in the mould of South African freedom icon Nelson Mandela, Raila became a consummate pragmatist on this endless landscape of compromises, reaching out to erstwhile political rivals in a series of in bold moves, each one that changed politics – and the fortunes of rival politicians – in Kenya.

Until now, Raila’s deal making has occurred arbitrarily, the only discernible pattern being his keenness to project himself as a Nelson Mandela – reaching out to his bitterest rivals and in so doing laundering their discredited political reputations.

Remarkably, Raila allied with former Vice President Kalonzo Musyoka to form the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy presidential ticket in 2013. Previously, his supporters had pilloried Kalonzo for years for saving Kibaki’s presidency at the height of 2007 post-election crisis, and later for his equivocal support for the new Constitution for which he earned the pejorative moniker of Watermelon – in reference to the fruit’s deceptive green exterior and red interior, the colours of rival ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ camps during the referendum for the 2010 constitution.

And although Raila had privately prosecuted George Saitoti over his role in the Goldenberg Scandal in which an estimated Sh100 billion was lost in foreign exchange compensation fraud – the State eventually took over this case and terminated it – he later got together with Saitoti during the 2002 campaigns that defeated KANU. To justify that deal, he reassigned the blame for Goldenberg to Musalia Mudavadi, who had succeeded Saitoti as finance minister.

A repentant Mudavadi would return to Raila’s good books during the referendum on the constitution in 2005, ultimately becoming Raila’s running mate in the 2007 campaign. After an acrimonious parting of ways in 2012, which saw the two separately seek the presidency, they were back together under the National Super Alliance for the 2017 elections; today, they appear headed for another falling out.

Suspicions that Raila might have brokered a deal that is personally beneficial to him has damaged his standing as the leader of an opposition movement that has delivered the greatest results on the continent over two decades.

When Moses Wetang’ula was forced to temporarily suspended from his Foreign Affairs docket in 2010 over corruption allegations around the purchase of an embassy building in Tokyo, Japan, it was Raila who campaigned for his reinstatement and later recruited him as a principal in what became the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy, the 2013 incarnation of NASA.

Recently, activist Okiya Omtatah spent a night in a police cell for skipping court when the mention of his case came up. He was charged with padlocking the office of Education minister Sam Ongeri in an attempt to force him out over corruption allegations back in 2011. Raila, as Prime Minister, had earlier suspended Ongeri from office alongside then Agriculture minister William Ruto but was countermanded by Kibaki. He has since joined Raila’s Orange Democratic Movement and was last year elected Senator in Kisii County.

The March 9 ‘handshake’ was coldly received by a sceptical public, many of whom had been radicalised by police violence after August 8, and had already bought into NASA’s Resistance Movement. Their disillusionment will likely limit Raila’s ability to deliver results, severely undermine his authority to negotiate new deals in future but also bring his past water-hosing of soiled politicians into sharp relief.