The Kenyan Supreme Court surprise decision at the beginning of September to annul the country’s presidential election wrong-footed most commentators. It has left egg on many, including the diplomatic corps as well as local and international observers, who had prematurely declared the election free, fair and credible, wiping egg of their embarrassed faces. But perhaps none have been as badly exposed as the country’s famously rambunctious private press.

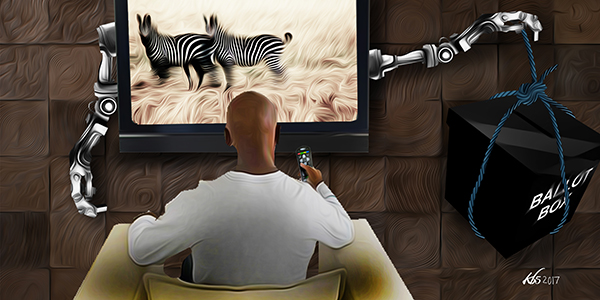

For more than half a century, the independent Kenyan media has carefully cultivated an image of vibrancy and defiance. It has frequently declared itself to be the people’s watchdog and its mission as speaking truth to power. However, for much of that time, the media has been more concerned about its survival and profitability in the face of an overbearing and dictatorial state.

This is not to say that the Kenya media has not been a thorn in the government’s backside. Quite the opposite. From the early days of colonialism, the media had been an arena for anti-government agitation. As Njeri Ng’ang’a details in her article on the Kenyan press, early as the 1920s, a nationalist press emerged that opposed colonial policies such as racial segregation and acted as a mouthpiece for the independence movement. From the 1930s through to the early 1950s, the colonial state enacted a series of ordinances meant to control publications it deemed seditious such as Sauti ya Mwafrika, Uhuru wa Mwafrika, African Leader and Inooro ria Agikuyu, culminating in a total ban following the 1952 Mau Mau uprising and the declaration of a State of Emergency. But as Kenya approached independence, a more conciliatory approach allowed the publishing of newspapers affiliated to local political associations, though these continued to be subjected to legal restrictions.

For more than half a century, the independent Kenyan media has carefully cultivated an image of vibrancy and defiance.

The post-Independence government retained many of the schizophrenic policies and attitudes it had inherited from its British forebears. The Kenyatta administration treated the private press with suspicion while still allowing it a limited room to operate and attempting to use it for propaganda and nation-building purposes. The regime of Kenyatta’s successor, Daniel arap Moi, who as Vice President had had a contentious relationship with the media, clamped down hard, especially once agitation for political reform and a new constitution begun in the late 1980s.

Newspapers such as The Daily Nation and newsmagazines such as Hilary Ngweno’s Weekly Review, the National Council of Churches of Kenya’s Target and Beyond, and others like Society, the Financial Review and the Economic Review, which had blazed a trail of independent and analytical reporting, often drew official ire and retribution. Many became targets of police raids, had journalists and editors detained without trial, were starved of advertising and some were eventually forced to close. Later, independent-minded reporters and editors at KTN, the first privately owned TV channel, would also feel Moi’s rage.

Survival, even defiance, in the face of such meant that by the time Moi was forced out of power, the press had a pretty solid reputation among Kenyans for fearlessness. Under Moi’s successor, Mwai Kibaki, however, the mainstream press appeared to settle into what Charles Onyango Obbo in 2013 described as Establishment mode – “they cease to aggressively challenge the political system, become vested in “stability”, and begin to worry about what will happen if the system breaks down.”

He writes: “The media had been part of the pro-democracy crusade, and Kibaki’s election was also its triumph. Many of its allies in civil society became big men and women in the Narc government. The pressure for the media to cash in its democracy activist chips was very high, as was the distraction of the seductions it faced from its former friends in civil society, who were now in government.”

Under Moi’s successor, Mwai Kibaki, however, the mainstream press appeared to settle into what Charles Onyango Obbo in 2013 described as Establishment mode – “they cease to aggressively challenge the political system, become vested in “stability”, and begin to worry about what will happen if the system breaks down.”

Following the 2007/8 post-election violence, during which much of the press -especially vernacular radio- was accused of fanning the ethnic hatred which led to the deaths of over 1600 people and displaced hundreds of thousands more, Kenyan media made a wholesale retreat from its role as a public watchdog. It essentially took the wrong lesson, conflating responsible reporting with incitement. This was to become manifest five years later in its coverage of the 2013 and 2017 elections.

In 2013, it was widely pilloried for seeming to gloss over the many problems with experienced during he elections under the banner of peace. I wrote at the time: “When nearly all the measures the [Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission] deployed to ensure transparency during the election failed, this was not allowed to intrude into the reverie. Instead the media continued to put on a show and we applauded them for it. Uncomfortable moments were photoshopped out of the familial picture.”

Which brings us to this year’s polls.

In a landmark ruling delivered in April last year and subsequently upheld by the Court of Appeal, the High Court had declared that elections results publicly declared at polling stations and at constituency tallying centres were final and not subject to alteration by the IEBC mandarins at the national tallying centre in Nairobi. One of the effects of this judgement was that the media no longer needed to wait on the official pronouncement of the outcome of the presidential election by IEBC officials at the Bomas of Kenya where the national tallying centre was located. It could simply send is reporters to either the 40,883 polling stations or the 290 constituency tallying centres across the country and then do its own sums.

Initially, the media gave every indication that it would do exactly this. And there is little doubt it had requisite capacity. Testifying on behalf of the Media Owners Association before the Senate in January, Royal Media Services’ S.K. Macharia revealed that the press had actually been monitoring results declared at polling stations in every election since 1992, including the contentious 2007 one. Macharia stated his intention to track the 2017 polls, vowing to take the IEBC or the government to court if it tried to block prevent it.

However, on polling day, none of the country’s media houses reported results as announced at either polling stations or constituency tallying centres, despite having correspondents posted there for that very purpose.

A month to the election, the government did issue such a threat. “If any media houses decides to release their own results we will switch them off immediately,” warned ICT Cabinet Secretary, Joe Mucheru. “Anybody can have their own tallying centres wherever they want but the final results will be those of the IEBC,” he added, eliciting howls of protest. “Mucheru’s warning to media houses is repugnant and retrogressive” The Standard declared in an editorial. Yet, perhaps tellingly, it fell to civil society to take the matter to court where Justice George Odunga opined thus: “It is, therefore, my view that a decision to shut down systems of any entity purporting to announce the results of the August 8 polls if they are not the ones released by the IEBC would be premature in light of provisions of Article 24 of the Constitution, which bars limitation of any right”.

However, on polling day, none of the country’s media houses reported results as announced at either polling stations or constituency tallying centres, despite having correspondents posted there for that very purpose. There seemed to be a consensus among them that they would only report on what was announced in Bomas. TV stations, after a day of covering the peaceful voting, retreated into streaming numbers beamed to them by the IEBC in Nairobi, even though there was little indication which polling stations they were coming from and despite an earlier promise from the IEBC that it would wait for constituency tallies. It was these numbers that the IEBC itself would later disown as mere “statistics”.

Even as disputes about the forms and tallies delayed the official announcement of the winner of the presidential poll, the media kept the tallies declared at constituency level to itself. As pundits such as myself ruled the airwaves with long-winded analysis of what was happening, the only numbers on show were those disputed “statistics”, not the promised independent tallies of final results. At times, the coverage degenerated into farce. KTN proudly offered the results of an “exit poll” it had commissioned which asked voters every question except the one that really mattered – How had they voted?

KTN proudly offered the results of an “exit poll” it had commissioned which asked voters every question except the one that really mattered – How had they voted?

As I write this, 38 days after the election and two weeks after the Supreme Court ruling annulling it, the media is yet to reveal what was publicly announced there or whether there indeed were announcements made as required by the law.

If, as asserted on Twitter by the Media Council of Kenya Deputy CEO, Victor Bwire, “the correct reliable tallies weren’t there to media in many cases. Those results weren’t posted as expected (sic)” then why didn’t the media report this? The coverage, or more accurately, lack of coverage, even mystified Martin Mulwa, a former senior journalist who had covered many an election campaign, with whom I sat on a KTN News panel for nearly 7 hours on election night. He kept wondering why announcements even from constituency centres like Starehe in Nairobi, a stone’s throw away the city centre where the show was being filmed from were not being broadcast live as had happened previously.

Speaking on NTV’s Press Pass a week after the election, veteran journalist Macharia Gaitho, who was helping run the Nation Media Group’s election coverage, maintained that he was yet to receive all the results from journalists posted at constituency tallying centres and promised to publish them once he did. A month later, the results are yet to materialize.

In the light of the Supreme Court finding that the election was characterized by illegalities and irregularities and subsequent revelations of serious tampering with the results, the performance of the Kenyan press takes on an even darker hue.

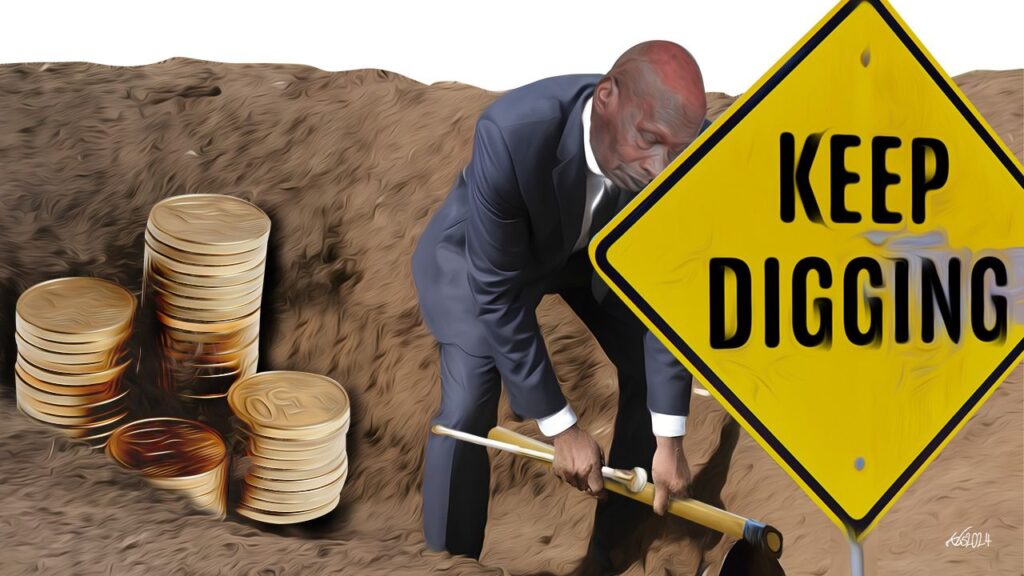

It raises profoundly disturbing questions about whether the media had been scared or bribed into silence. “It now appears that some media houses were ordered not to report on constituency contests, which might lead to suspicion that something deeper was amiss,” Charles Hornsby, author of Kenya; A History since Independence, wrote in The Elephant. In an article published in the Washington Post, I opined that the media had sold its soul for millions of illegal advertising shillings.

In the light of the Supreme Court finding that the election was characterized by illegalities and irregularities and subsequent revelations of serious tampering with the results, the performance of the Kenyan press takes on an even darker hue. Had the polling station counts and constituency tallies been reported, the public would have had an independent way of verifying whether what was being announced in Bomas was a true and accurate reflection of what how they had voted. By not doing so, the media has opened itself up to accusations of colluding in the stealing of the election.

Further, its refusal to provide timely coverage of the small election-related protests that broke out in the run up to the official declaration of the President-Elect, many of which were covered in the international press, opened the door to a veritable flood of fake news on social media which further polarized the country.

Kenyans have repeatedly stood up for the media, but when it came the media’s turn to stand up for them, it was nowhere to be seen.

It is a bitter pill for Kenyans to swallow. The fight to secure freedom of the press has seen many lose their lives and endure police beatings as well as incarceration. A media that today takes so lightly its duty to hold the authorities to account and to keep the public informed in effect spits on that sacrifice and seriously undermines the effort to democratize the country.

Kenyans have repeatedly stood up for the media, but when it came the media’s turn to stand up for them, it was nowhere to be seen. The fresh presidential elections slated for October 17 offers Kenyan media another shot at redemption. Whether it will take the opportunity to atone for its previous and continuing misdeeds however remains to be seen.

By Patrick Gathara

Mr Gathara is a social and political commentator and cartoonist based in Nairobi