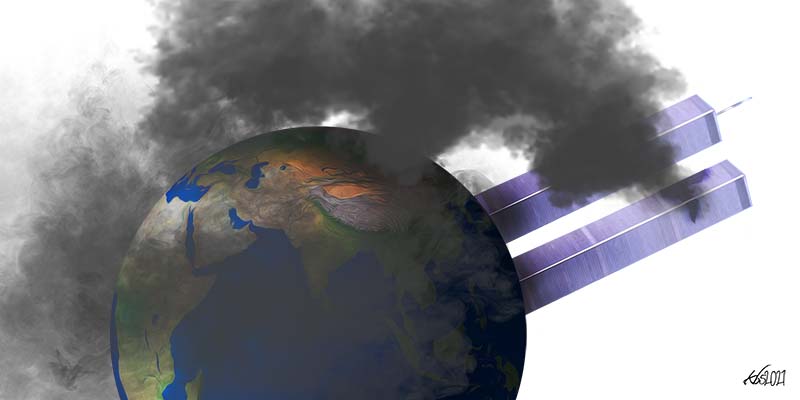

It was surreal, almost unbelievable in its audacity. Incredulous images of brazen and coordinated terrorist attacks blazoned television screens around the world. The post-Cold War lone and increasingly lonely superpower was profoundly shaken, stunned, and humbled. It was an attack that was destined to unleash dangerous disruptions and destabilize the global order. That was 9/11, whose twentieth anniversary fell this weekend.

Popular emotions that day and in the days and weeks and months that followed exhibited fear, panic, anger, frustration, bewilderment, helplessness, and loss. Subsequent studies have shown that in the early hours of the terrorist attacks confusion and apprehension reigned even at the highest levels of government. However, before long it gave way to an all-encompassing overreaction and miscalculation that set the US on a catastrophic path.

The road to ruin over the next twenty years was paved in those early days after 9/11 in an unholy contract of incendiary expectations by the public and politicians born out of trauma and hubris. There was the nation’s atavistic craving for a bold response, and the leaders’ quest for a millennial mission to combat a new and formidable global evil. The Bush administration was given a blank check to craft a muscular invasion to teach the terrorists and their sponsors an unforgettable lesson of America’s lethal power and unequalled global reach.

Like most people over thirty, I remember that day vividly as if it was yesterday. I was on my first, and so far only sabbatical in my academic year. As a result, I used to work long into the night and wake up late in the morning. So I was surprised when I got a sudden call from my wife who was driving to campus to teach. Frantically, she told me the news was reporting unprecedented terrorist attacks on the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Virginia, and that a passenger plane had crashed in Pennsylvania. There was personal anguish in her voice: her father worked at the Pentagon. I jumped out of bed, stiffened up, and braced myself. Efforts to get hold of her mother had failed because the lines were busy, and she couldn’t get through.

When she eventually did, and to her eternal relief and that of the entire family, my mother-in-law reported that she had received a call from her husband. She said he was fine. He had reported to work later than normal because he had a medical appointment that morning. That was how he survived, as the wing of the Pentagon that was attacked was where he worked. However, he lost many colleagues and friends. Such is the capriciousness of life, survival, and death in the wanton assaults of mass terrorism.

For the rest of that day and in the dizzying aftermath, I read and listened to American politicians, pundits, and scholars trying to make sense of the calamity. The outrage and incredulity were overwhelming, and the desire for crushing retribution against the perpetrators palpable. The dominant narrative was one of unflinching and unreflexive national sanctimoniousness; America was attacked by the terrorists for its way of life, for being what it was, the world’s unrivalled superpower, a shining nation on the hill, a paragon of civilization, democracy, and freedom.

Critics of the country’s unsavoury domestic realities of rampant racism, persistent social exclusion, and deepening inequalities, and its unrelenting history of imperial aggression and military interventions abroad were drowned out in the clamour for revenge, in the collective psychosis of a wounded pompous nation.

9/11 presented a historic shock to America’s sense of security and power, and created conditions for profound changes in American politics, economy, and society, and in the global political economy. It can be argued that it contributed to recessions of democracy in the US itself, and in other parts of the world including Africa, in so far as it led to increased weaponization of religious, ethnic, cultural, national, and regional identities, as well as the militarization and securitization of politics and state power. America’s preoccupation with the ill-conceived, destructive, and costly “war on terror” accelerated its demise as a superpower, and facilitated the resurgence of Russia and the rise of China.

Of course, not every development since 9/11 can be attributed to this momentous event. As historians know only too well, causation is not always easy to establish in the messy flows of historical change. While cause and effect lack mathematical precision in humanity’s perpetual historical dramas, they reflect probabilities based on the preponderance of existing evidence. That is why historical interpretations are always provisional, subject to the refinement of new research and evidence, theoretical and analytical framing.

America’s preoccupation with the ill-conceived, destructive, and costly “war on terror” accelerated its demise as a superpower.

However, it cannot be doubted that the trajectories of American and global histories since 9/11 reflect the latter’s direct and indirect effects, in which old trends were reinforced and reoriented, new ones fostered and foreclosed, and the imperatives and orbits of change reconstituted in complex and contradictory ways.

In an edited book I published in 2008, The Roots of African Conflicts, I noted in the introductory chapter entitled “The Causes & Costs of War in Africa: From Liberation Struggles to the ‘War on Terror’” that this war combined elements of imperial wars, inter-state wars, intra-state wars and international wars analysed extensively in the chapter and parts of the book. It was occurring in the context of four conjuctures at the turn of the twenty-first century, namely, globalization, regionalization, democratization, and the end of the Cold War.

I argued that the US “war on terror” reflected the impulses and conundrum of a hyperpower. America’s hysterical unilateralism, which was increasingly opposed even by its European allies, represented an attempt to recentre its global hegemony around military prowess in which the US remained unmatched. It was engendered by imperial hubris, the arrogance of hyperpower, and a false sense of exceptionalism, a mystical belief in the country’s manifest destiny.

I noted the costs of the war were already high within the United States itself. It threatened the civil liberties of its citizens and immigrants in which Muslims and people of “Middle Eastern” appearance were targeted for racist attacks. The nations identified as rogue states were earmarked for crippling sanctions, sabotage and proxy wars. In the treacherous war zones of Afghanistan and Iraq it left a trail of destruction in terms of deaths and displacement for millions of people, social dislocation, economic devastation, and severe damage to the infrastructures of political stability and sovereignty.

More than a decade and a half after I wrote my critique of the “war on terror”, its horrendous costs on the US itself and on the rest of the world are much clearer than ever. Some of the sharpest critiques have come from American scholars and commentators for whom the “forever wars” were a disaster and miscalculation of historic proportions. Reading the media reports and academic articles in the lead-up to the 20th anniversary of 9/11, I’ve been struck by many of the critical and exculpatory reflections and retrospectives.

Hindsight is indeed 20/20; academics and pundits are notoriously subject to amnesia in their wilful tendency to retract previous positions as a homage to their perpetual insightfulness. Predictably, there are those who remain defensive of America’s response to 9/11. Writing in September 2011, one dismissed what he called the five myths of 9/11: that the possibility of hijacked airliners crashing into buildings was unimaginable; the attacks represented a strategic success for al-Qaeda; Washington overreacted; a nuclear terrorist attack is an inevitability; and civil liberties were decimated after the attacks.

Marking the 20th anniversary, another commentator maintains that America’s forever wars must go on because terrorism has not been vanquished. “Ending America’s deployment in Afghanistan is a significant change. But terrorism, whether from jihadists, white nationalists, or other sources, is part of life for the indefinite future, and some sort of government response is as well. The forever war goes on forever. The question isn’t whether we should carry it out—it’s how.”

Some of the sharpest critiques have come from American scholars and commentators for whom the “forever wars” were a disaster and miscalculation of historic proportions.

To understand the traumatic impact of 9/11 on the US, and its disastrous overreaction, it is helpful to note that in its history, the American homeland had largely been insulated from foreign aggression. The rare exceptions include the British invasion in the War of 1812 and the Japanese military strike on Pearl Harbour in Honolulu, Hawaii in December 1941 that prompted the US to formally enter World War II.

Given this history, and America’s post-Cold War triumphalism, 9/11 was inconceivable to most Americans and to much of the world. Initially, the terrorist attacks generated national solidarity and international sympathy. However, both quickly dissipated because of America’s overweening pursuit of a vengeful, misguided, haughty, and obtuse “war on terror”, which was accompanied by derisory and doomed neo-colonial nation-building ambitions that were dangerously out of sync in a postcolonial world.

It can be argued that 9/11 profoundly transformed American domestic politics, the country’s economy, and its international relations. The puncturing of the bubble of geographical invulnerability and imperial hubris left deep political and psychic pain. The terrorist attacks prompted an overhaul of the country’s intelligence and law-enforcement systems, which led to an almost Orwellian reconceptualization of “homeland security” and formation of a new federal department by that name.

The new department, the largest created since World War II, transformed immigration and border patrols. It perilously conflated intelligence, immigration, and policing, and helped fabricate a link between immigration and terrorism. It also facilitated the militarization of policing in local and state jurisdictions as part of a vast and amorphous war on domestic and international terrorism. Using its new counter-insurgence powers, the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency went to work. According to one report, in the British paper The Guardian, “In 2005, it carried out 1,300 raids against businesses employing undocumented immigrants; the next year there were 44,000.”

By 2014, the national security apparatus comprised more than 5 million people with security clearances, or 1.5 per cent of the country’s population, which risked, a story in The Washington Post noted, “making the nation’s secrets less, well, secret.” Security and surveillance seeped into mundane everyday tasks from checks at airports to entry at sporting and entertainment events.

The puncturing of the bubble of geographical invulnerability and imperial hubris left deep political and psychic pain.

As happens in the dialectical march of history, enhanced state surveillance including aggressive policing fomented the countervailing struggles on both the right and left of the political spectrum. On the progressive side was the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, and rejuvenated gender equality and immigrants’ rights activists, and on the reactionary side were white supremacist militias and agitators including those who carried the unprecedented violent attack on the US Capitol on 6 January 2021. The latter were supporters of defeated President Trump who invaded the sanctuaries of Congress to protest the formal certification of Joe Biden’s election to the presidency.

Indeed, as The Washington Post columnist, Colbert King recently reminded us, “Looking back, terrorist attacks have been virtually unrelenting since that September day when our world was turned upside down. The difference, however, is that so much of today’s terrorism is homegrown. . . . The broad numbers tell a small part of the story. For example, from fiscal 2015 through fiscal 2019, approximately 846 domestic terrorism subjects were arrested by or in coordination with the FBI. . . . The litany of domestic terrorism attacks manifests an ideological hatred of social justice as virulent as the Taliban’s detestation of Western values of freedom and truth. The domestic terrorists who invaded and degraded the Capitol are being rebranded as patriots by Trump and his cultists, who perpetuate the lie that the presidential election was rigged and stolen from him.”

Thus, such is the racialization of American citizenship and patriotism, and the country’s dangerous spiral into partisanship and polarization that domestic white terrorists are tolerated by significant segments of society and the political establishment, as is evident in the strenuous efforts by the Republicans to frustrate Congressional investigation into the January 6 attack on Congress.

In September 2001, incredulity at the foreign terrorist attacks exacerbated the erosion of popular trust in the competence of the political class that had been growing since the restive 1960s and crested with Watergate in the 1970s, and intensified in the rising political partisanship of the 1990s. Conspiracy theories about 9/11 rapidly proliferated, fuelling the descent of American politics and public discourse into paranoia, which was to be turbocharged as the old media splintered into angry ideological solitudes and the new media incentivized incivility, solipsism, and fake news. 9/11 accelerated the erosion of American democracy by reinforcing popular fury and rising distrust of elites and expertise, which facilitated the rise of the disruptive and destructive populism of Trump.

9/11 offered a historic opportunity to seek and sanctify a new external enemy in the continuous search for a durable foreign foe to sustain the creaking machinery of the military, industrial, media and ideological complexes of the old Cold War. The US settled not a national superpower, as there was none, notwithstanding the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, but on a religion, Islam. Islamophobia tapped into the deep recesses in the Euro-American imaginary of civilizational antagonisms and anxieties between the supposedly separate worlds of the Christian West and Muslim East, constructs that elided their shared historical, spatial, and demographic affinities.

After 9/11, Muslims and their racialized affinities among Arabs and South Asians joined America’s intolerant tent of otherness that had historically concentrated on Black people. One heard perverse relief among Blacks that they were no longer the only ones subject to America’s eternal racial surveillance and subjugation. The expanding pool of America’s undesirable and undeserving racial others reflected growing anxieties by segments of the white population about their declining demographic, political and sociocultural weight, and the erosion of the hegemonic conceits and privileges of whiteness.

9/11 accelerated the erosion of American democracy by reinforcing popular fury and rising distrust of elites and expertise.

This helped fuel the Trumpist populist reactionary upsurge and the assault on democracy by the Republican Party. In the late 1960s, the party devised the Southern Strategy to counter and reverse the limited redress of the civil rights movement. 9/11 allowed the party to shed its camouflage as a national party and unapologetically adorn its white nativist and chauvinistic garbs. So it was that a country which went to war after 9/11 purportedly “united in defense of its values and way life,” emerged twenty years later “at war with itself, its democracy threatened from within in a way Osama bin Laden never managed.”

The economic effects of the misguided “war on terror” and its imperilled “nation building” efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq were also significant. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the subsequent demise of the Soviet Union and its socialist empire in central and Eastern Europe, there were expectations of an economic dividend from cuts in excessive military expenditures. The pursuit of military cuts came to a screeching halt with 9/11.

On the tenth anniversary of 9/11 Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize winner for economics, noted ruefully that Bush’s “was the first war in history paid for entirely on credit. . . . Increased defense spending, together with the Bush tax cuts, is a key reason why America went from a fiscal surplus of 2% of GDP when Bush was elected to its parlous deficit and debt position today. . . . Moreover, as Bilmes and I argued in our book The Three Trillion Dollar War, the wars contributed to America’s macroeconomic weaknesses, which exacerbated its deficits and debt burden. Then, as now, disruption in the Middle East led to higher oil prices, forcing Americans to spend money on oil imports that they otherwise could have spent buying goods produced in the US. . . .”

He continued, “But then the US Federal Reserve hid these weaknesses by engineering a housing bubble that led to a consumption boom.” The latter helped trigger the financial crisis that resulted in the Great Recession of 2008-2009. He concluded that these wars had undermined America’s and the world’s security beyond Bin Laden’s wildest dreams.

The costs of the “forever wars” escalated over the next decade. According to a report in The Wall Street Journal, from 2001 to 2020 the US security apparatuses spent US$230 billion a year, for a total of US$5.4 trillion, on these dubious efforts. While this represented only 1 per cent of the country’s GDP, the wars continued to be funded by debt, further weakening the American economy. The Great Recession of 2008-09 added its corrosive effects, all of which fermented the rise of contemporary American populism.

Thanks to these twin economic assaults, the US largely abandoned investing in the country’s physical and social infrastructure that has become more apparent and a drag on economic growth and the wellbeing for tens of millions of Americans who have slid from the middle class or are barely hanging onto it. This has happened in the face of the spectacular and almost unprecedented rise of China as America’s economic and strategic rival that the former Soviet Union never was.

The jingoism of America’s “war on terror” quickly became apparent soon after 9/11. The architect of America’s twenty-year calamitous imbroglio, the “forever wars,” President George W Bush, who had found his swagger from his limp victory in the hanging chads of Florida, brashly warned America’s allies and adversaries alike: “You’re either with us or against us in the fight against terror.”

Through this uncompromising imperial adventure in the treacherous geopolitical quicksands of the Middle East, including “the graveyard of empires,” Afghanistan, the US succeeded in squandering the global sympathy and support it had garnered in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 not only from its strategic rivals but also from its Western allies. The notable exception was the supplicant British government under “Bush’s poodle”, Prime Minister Tony Blair, desperately clinging to the dubious loyalty and self-aggrandizing myth of a “special relationship”.

The neglect of international diplomacy in America’s post-9/11 politics of vengeance was of course not new. It acquired its implacable brazenness from the country’s post-Cold War triumphalism as the lone superpower, which served to turn it into a lonely superpower. 9/11 accelerated the gradual slide for the US from the pedestal of global power as diplomacy and soft power were subsumed by demonstrative and bellicose military prowess.

The disregard for diplomacy began following the defeat of the Taliban in 2001. In the words of Jonathan Powell that are worth quoting at length, “The principal failure in Afghanistan was, rather, to fail to learn, from our previous struggles with terrorism, that you only get to a lasting peace when you have an inclusive negotiation – not when you try to impose a settlement by force. . . . The first missed opportunity was 2002-04. . . . After the Taliban collapsed, they sued for peace. Instead of engaging them in an inclusive process and giving them a stake in the new Afghanistan, the Americans continued to pursue them, and they returned to fighting. . . . There were repeated concrete opportunities to start negotiations with the Taliban from then on – at a time when they were much weaker than today and open to a settlement – but political leaders were too squeamish to be seen publicly dealing with a terrorist group. . . . We have to rethink our strategy unless we want to spend the next 20 years making the same mistakes over and over again. Wars don’t end for good until you talk to the men with the guns.”

The all-encompassing counter-terrorism strategy adopted after 9/11 bolstered American fixation with military intervention and solutions to complex problems in various regional arenas including the combustible Middle East. In an increasingly polarized capital and nation, only the Defense Department received almost universal support in Congressional budget appropriations and national public opinion. Consequently, the Pentagon accounts for half of the federal government’s discretionary spending. In 2020, military expenditure in the US reached US$778 billion, higher than the US$703.6 billion spent by the next nine leading countries in terms of military expenditure, namely, China (US$252 billion), India (US$72.9 billion), Russia (US$61.7 billion), United Kingdom (US$59.2 billion), Saudi Arabia (US$57.5 billion), Germany (US$52.6 billion), France (US$52.7 billion), Japan (US$49.1 billion) and South Korea (US$45.7 billion).

Under the national delirium of 9/11, the clamour for retribution was deafening as evident in Congress and the media. In the United States Senate, the Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) against the perpetrators of 9/11, which became law on 18 September 2001, nine days after the terrorist attacks, was approved by 98, none against, and two did not vote. In the House of Representatives, the vote tally was 420 ayes, 1 nay (the courageous Barbara Lee of California), and 10 not voting.

9/11 accelerated the gradual slide for the US from the pedestal of global power as diplomacy and soft power were subsumed by demonstrative and bellicose military prowess.

By the time the Authorization for the Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 was taken in the two houses of Congress, and became law on 16 October 2002, the ranks of cooler heads had begun to expand but not enough to put a dent on the mad scramble to expand the “war on terror”. In the House of Representatives 296 voted yes, 133 against, and three did not vote, while in the Senate the vote was 77 for and 23 against.

Beginning with Bush, and for subsequent American presidents, the law became an instrument of militarized foreign policy to launch attacks against various targets. Over the next two decades, “the 2001 AUMF has been invoked more than 40 times to justify military operations in 18 countries, against groups who had nothing to do with 9/11 or al-Qaida. And those are just the operations that the public knows about.”

Almost twenty years later, on 17 June 2021, the House voted 268-161 to repeal the authorization of 2002. By then, it had of course become clear that the “forever wars” in Afghanistan and Iraq were destined to become a monumental disaster and defeat in the history of the United States that has sapped the country of its trust, treasure, and global standing and power. But revoking the law did not promise to end the militarized reflexes of counter-insurgence it had engendered.

The “forever wars” consumed and sapped the energies of all administrations after 2001, from Bush to Obama to Trump to Biden. As the wars lost popular support in the US, aspiring politicians hoisted their fortunes on proclaiming their opposition. Opposition to the Iraq war was a key plank of Obama’s electoral appeal, and the pledge to end these wars animated the campaigns of all three of Bush’s successors. The logic of counterterrorism persisted even under the Obama administration that retired the phrase “war on terror” but not its practices; it expanded drone warfare by authorizing an estimated 542 drone strikes which killed 3,797 people, including 324 civilians.

The Trump Administration signed a virtual surrender pact, a “peace agreement,” with the Taliban on 29 February 2020, that was unanimously supported by the UN Security Council. Under the agreement, NATO undertook to gradually withdraw its forces and all remaining troops by 1 May 2021, while the Taliban pledged to prevent al-Qaeda from operating in areas it controlled and to continue talks with the Afghan government that was excluded from the Doha negotiations between the US and the Taliban.

The “forever wars” consumed and sapped the energies of all administrations after 2001, from Bush to Obama to Trump to Biden.

Following the signing of the Doha Agreement, the Taliban insurgency intensified, and the incoming Biden administration indicated it would honour the commitment of the Trump administration for a complete withdrawal, save for a minor extension from 1 May to 31 August 2021. Two weeks before the American deadline, on 15 August 2021, Taliban forces captured Kabul as the Afghan military and government melted away in a spectacular collapse. A humiliated United States and its British lackey scrambled to evacuate their embassies, staff, citizens, and Afghan collaborators.

Thus, despite having the world’s third largest military, and the most technologically advanced and best funded, the US failed to prevail in the “forever wars”. It was routed by the ill-equipped and religiously fanatical Taliban, just like a generation earlier it had been hounded out of Vietnam by vastly outgunned and fiercely determined local communist adversaries. Some among America’s security elites, armchair think tanks, and pundits turned their outrage on Biden whose execution of the final withdrawal they faulted for its chaos and for bringing national shame, notwithstanding overwhelming public support for it.

Underlying their discomfiture was the fact that Biden’s logic, a long-standing member of the political establishment, “carried a rebuke of the more expansive aims of the post-9/11 project that had shaped the service, careers, and commentary of so many people,” writes Ben Rhodes, deputy national security adviser in the Obama administration from 2009-2017. He concludes, “In short, Biden’s decision exposed the cavernous gap between the national security establishment and the public, and forced a recognition that there is going to be no victory in a ‘war on terror’ too infused with the trauma and triumphalism of the immediate post-9/11 moment.”

The predictable failure of the American imperial mission in Afghanistan and Iraq left behind wanton destruction of lives and society in the two countries and elsewhere where the “war on terror” was waged. The resistance to America’s imperial aggression, including that by the eventually victorious Taliban, was in part fanned and sustained by the indiscriminate attacks on civilian populations, the dereliction of imperial invaders in understanding and engaging local communities, and the sheer historical reality that imperial invasions and “nation building” projects are relics of a bygone era and cannot succeed in the post-colonial world.

Reflections by the director of Yale’s International Leadership Center capture the costly ignorance of delusional imperial adventures. “Our leaders repeatedly told us that we were heroes, selflessly serving over there to keep Americans safe in their beds over here. They spoke with fervor about freedom, about the exceptional American democratic system and our generosity in building Iraq. But we knew so little about the history of the country. . . . No one mentioned that the locals might not be passive recipients of our benevolence, or that early elections and a quickly drafted constitution might not achieve national consensus but rather exacerbate divisions in Iraq society. The dismantling of the Iraq state led to the country’s descent into civil war.”

The global implications of the “war on terror” were far reaching. In the region itself, Iran and Pakistan were strengthened. Iran achieved a level of influence in Iraq and in several parts of the region that seemed inconceivable at the end of the protracted and devastating 1980-1988 Iraq-Iran War that left behind mass destruction for hundreds of thousands of people and the economies of the two countries. For its part, Pakistan’s hand in Afghanistan was strengthened.

In the meantime, new jihadist movements emerged from the wreckage of 9/11 superimposed on long-standing sectarian and ideological conflicts that provoked more havoc in the Middle East, and already unstable adjacent regions in Asia and Africa. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, Africa’s geopolitical stock for Euro-America began to rise bolstered by China’s expanding engagements with the continent and the “war on terror”. On the latter, the US became increasingly concerned about the growth of jihadist movements, and the apparent vulnerability of fragile states as potential sanctuaries of global terrorist networks.

As I’ve noted in a series of articles, US foreign policies towards Africa since independence have veered between humanitarian and security imperatives. The humanitarian perspective perceives Africa as a zone of humanitarian disasters in need of constant Western social welfare assistance and interventions. It also focuses on Africa’s apparent need for human rights modelled on idealized Western principles that never prevented Euro-America from perpetrating the barbarities of slavery, colonialism, the two World Wars, other imperial wars, and genocides, including the Holocaust.

Under the security imperative, Africa is a site of proxy cold and hot wars among the great powers. In the days of the Cold War, the US and Soviet Union competed for friends and fought foes on the continent. In the “war on terror”, Africa emerged as a zone of Islamic radicalization and terrorism. It was not lost that in 1998, three years before 9/11, US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania were attacked. Suddenly, Africa’s strategic importance, which had declined precipitously after the end of the Cold War, rose, and the security paradigm came to complement, compete, and conflict with the humanitarian paradigm as US Africa policy achieved a new strategic coherence.

The cornerstone of the new policy is AFRICOM, which was created out of various regional military programmes and initiatives established in the early 2000s, such as the Combined Joint Task Force-Horn Africa, and the Pan-Sahel Initiative, both established in 2002 to combat terrorism. It began its operations in October 2007. Prior to AFRICOM’s establishment, the military had divided up its oversight of African affairs among the U.S. European Command, based in Stuttgart, Germany; the U.S. Central Command, based in Tampa, Florida; and the U.S. Pacific Command, based in Hawaii.

In the meantime, the “war on terror” provided alibis for African governments, as elsewhere, to violate or vitiate human rights commitments and to tighten asylum laws and policies. At the same time, military transfers to countries with poor human rights records increased. Many an African state rushed to pass broadly, badly or cynically worded anti-terrorism laws and other draconian procedural measures, and to set up special courts or allow special rules of evidence that violated fair trial rights, which they used to limit civil rights and freedoms, and to harass, intimidate, and imprison and crackdown on political opponents. This helped to strengthen or restore a culture of impunity among the security forces in many countries.

Africa’s geopolitical stock for Euro-America began to rise bolstered by China’s expanding engagements with the continent and the “war on terror”.

In addition to the restrictions on political and civil rights among Africa’s autocracies and fledgling democracies, the subordination of human rights concerns to anti-terrorism priorities, the “war on terror” exacerbated pre-existing political tensions between Muslim and Christian populations in several countries and turned them increasingly violent. In the twenty years following its launch, jihadist groups in Africa grew considerably and threatened vast swathes of the continent from Northern Africa to the Sahel to the Horn of Africa to Mozambique.

According to a recent paper by Alexandre Marc, the Global Terrorism Index shows that “deaths linked to terrorist attacks declined by 59% between 2014 and 2019 — to a total of 13,826 — with most of them connected to countries with jihadi insurrections. However, in many places across Africa, deaths have risen dramatically. . . . Violent jihadi groups are thriving in Africa and in some cases expanding across borders. However, no states are at immediate risk of collapse as happened in Afghanistan.”

If much of Africa benefited little from the US-led global war on terrorism, it is generally agreed China reaped strategic benefits from America’s preoccupation in Afghanistan and Iraq that consumed the latter’s diplomatic, financial, and moral capital. China has grown exponentially over the past twenty years and its infrastructure has undergone massive modernization even as that in the US has deteriorated. In 2001, “the Chinese economy represented only 7% of the world GDP, it will reach the end of the year [2021] with a share of almost 18%, and surpassing the USA. It was also during this period that China became the biggest trading partner of more than one hundred countries around the world, advancing on regions that had been ‘abandoned’ by American diplomacy.”

As elsewhere, China adopted the narrative of the “war on terror” to silence local dissidents and “to criminalize Uyghur ethnicity in the name of ‘counter-terrorism’ and ‘de-extremification.” The Chinese Communist Party “now had a convenient frame to trace all violence to an ‘international terrorist organization’ and connect Uyghur religious, cultural and linguistic revivals to ‘separatism.’ Prior to 9/11, Chinese authorities had depicted Xinjiang as prey to only sporadic separatist violence. An official Chinese government White Paper published in January 2002 upended that narrative by alleging that Xinjiang was beset by al-Qaeda-linked terror groups. Their intent, they argued, was the violent transformation of Xinjiang into an independent ‘East Turkistan.’”

The United States went along with that. “Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage in September 2002 officially designated ETIM a terrorist entity. The U.S. Treasury Department bolstered that allegation by attributing solely to ETIM the same terror incident data, (“over 200 acts of terrorism, resulting in at least 162 deaths and over 440 injuries”) that the Chinese government’s January 2002 White Paper had attributed to various terrorist groups. That blanket acceptance of the Chinese government’s Xinjiang terrorism narrative was nothing less than a diplomatic quid pro quo, Boucher said. “It was done to help gain China’s support for invading Iraq. . . .”

Similarly, America’s “war on terror” gave Russia the space to begin flexing its muscles. Initially, it appeared relations between the US and Russia could be improved by sharing common cause against Islamic extremism. Russia even shared intelligence on Afghanistan, where the Soviet Union had been defeated more than a decade earlier. But the honeymoon, which coincided with Vladimir Putin’s ascension to power, proved short-lived.

It is generally agreed China reaped strategic benefits from America’s preoccupation in Afghanistan and Iraq that consumed the latter’s diplomatic, financial, and moral capital.

According to Angela Stent, American and Russian “expectations from the new partnership were seriously mismatched. An alliance based on one limited goal — to defeat the Taliban — began to fray shortly after they were routed. The Bush administration’s expectations of the partnership were limited.” It believed that in return for Moscow’s assistance in the war on terror, “it had enhanced Russian security by ‘cleaning up its backyard’ and reducing the terrorist threat to the country. The administration was prepared to stay silent about the ongoing war in Chechnya and to work with Russia on the modernization of its economy and energy sector and promote its admission to the World Trade Organization.”

For his part, Putin had more extensive expectations, to have an “equal partnership of unequals,” to secure “U.S. recognition of Russia as a great power with the right to a sphere of influence in the post-Soviet space. Putin also sought a U.S. commitment to eschew any further eastern enlargement of NATO. From Putin’s point of view, the U.S. failed to fulfill its part of the post-9/11 bargain.”

Nevertheless, during the twenty years of America’s “forever wars” Russia recovered from the difficult and humiliating post-Soviet decade of domestic and international weakness. It pursued its own ruthless counter-insurgency strategy in the North Caucasus using language from the American playbook despite the differences. It also began to flex its muscles in the “near abroad”, culminating in the seizure of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014.

The US “war on terror” and its execution that abnegated international law and embraced a culture of gratuitous torture and extraordinary renditions severely eroded America’s political and moral stature and pretensions. The enduring contradictions and hypocrisies of American foreign policy rekindled its Cold War propensities for unholy alliances with ruthless regimes that eagerly relabelled their opponents terrorists.

While the majority of the 9/11 attackers were from Saudi Arabia, the antediluvian and autocratic Saudi regime continued to be a staunch ally of the United States. Similarly, in Egypt the US assiduously coddled the authoritarian regime of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi that seized power from the short-lived government of President Mohamed Morsi that emerged out of the Arab Spring that electrified the world for a couple of years from December 2010.

For the so-called international community, the US-led “war on terror” undermined international law, the United Nations, and global security and disarmament, galvanized terrorist groups, diverted much-needed resources for development, and promoted human rights abuses by providing governments throughout the world with a new license for torture and abuse of opponents and prisoners. In my book mentioned earlier, I quoted the Council on Foreign Relations, which noted in 2002, that the US was increasingly regarded as “arrogant, self-absorbed, self-indulgent, and contemptuous of others.” A report by Human Rights Watch in 2005 singled out the US as a major factor in eroding the global human rights system.

Twenty years after 9/11, the US has little to show for its massive investment of trillions of dollars and the countless lives lost. Writing in The Atlantic magazine on the 20th anniversary of 9/11, Ali Soufan contends, “U.S. influence has been systematically dismantled across much of the Muslim world, a process abetted by America’s own mistakes. Sadly, much of this was foreseen by the very terrorists who carried out those attacks.”

Soufan notes, “The United States today does not have so much as an embassy in Afghanistan, Iran, Libya, Syria, or Yemen. It demonstrably has little influence over nominal allies such as Pakistan, which has been aiding the Taliban for decades, and Saudi Arabia, which has prolonged the conflict in Yemen. In Iraq, where almost 5,000 U.S. and allied troops have died since 2003, America must endure the spectacle of political leaders flaunting their membership in Iranian-backed groups, some of which the U.S. considers terrorist organizations.”

A report by Human Rights Watch in 2005 singled out the US as a major factor in eroding the global human rights system.

The day after 9/11, the French newspaper Le Monde declared, “In this tragic moment, when words seem so inadequate to express the shock people feel, the first thing that comes to mind is: We are all Americans!” Now that the folly of the “forever wars” is abundantly clear, can Americans learn to say and believe, “We’re an integral part of the world,” neither immune from the perils and ills of the world, nor endowed with exceptional gifts to solve them by themselves. Rather, to commit to righting the massive wrongs of its own society, its enduring injustices and inequalities, with the humility, graciousness, reflexivity, and self-confidence of a country that practices what it preaches.

Can America ever embrace the hospitality of radical openness to otherness at home and abroad? American history is not encouraging. If the United States wants to be taken seriously as a bastion and beacon of democracy, it must begin by practicing democracy. This would entail establishing a truly inclusive multiracial and multicultural polity, abandoning the antiquated electoral college system through which the president is elected that gives disproportionate power to predominantly white small and rural states, getting rid of gerrymandering that manipulates electoral districts and caters to partisan extremists, and stopping the cancer of voter suppression aimed at disenfranchising Blacks and other racial and ethnic minorities.

When I returned to my work as Director of the Center for African Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in the fall of 2002, following the end of my sabbatical, I found the debates of the 1990s about the relevance of area studies had been buried with 9/11. Now, it was understood, as it was when the area studies project began after World War II, that knowledges of specific regional, national and local histories, as well as languages and cultures, were imperative for informed and effective foreign policy, that fancy globalization generalizations and models were not a substitute for deep immersion in area studies knowledges.

If the United States wants to be taken seriously as a bastion and beacon of democracy, it must begin by practicing democracy.

However, area studies were now increasingly subordinated to the security imperatives of the war on terror, reprising the epistemic logic of the Cold War years. Special emphasis was placed on Arabic and Islam. This shift brought its own challenges that area studies programmes and specialists were forced to deal with. Thus, the academy, including the marginalized enclave of area studies, did not escape the suffocating tentacles of 9/11 that cast its shadow on every aspect of American politics, society, economy, and daily life.

Whither the future? A friend of mine in Nairobi, John Githongo, an astute observer of African and global affairs and the founder of the popular and discerning online magazine, The Elephant, wrote me to say, “America’s defeat in Afghanistan may yet prove more consequential than 9/11”. That is indeed a possibility. Only time will tell.