Grief and relief

On March 17, 2021, the fifth president of Tanzania John Joseph Pombe Magufuli, aged 61, died a few months after beginning his second term in office. It was a ‘dramatic’ exit for a person who had almost single-handedly (some would say heavy-handedly) ruled the country for the preceding five years. The reaction of the Tanzanian populace was as dramatic, if not extreme. Large sections of down-trodden (‘wanyonge’ in Swahili) people in urban and semi-urban areas were struck with disbelief and grief. Among them were motorbike taxi drivers (‘bodaboda’), street hawkers (‘machinga’), women food vendors (‘mama Ntilie’) and small entrepreneurs (‘wajasiriamali’). At the other end of the spectrum were sections of civil society elites, leaders and members of opposition parties, and a section of non-partisan intelligentsia who heaved a sigh of relief. Barring a few insensitive opposition political figures in exile, most in the middle-class group did not openly express or exhibit their relief, as African culture dictates, until after the 21-day mourning period had passed. In between the extremes were large sections of politicians and senior functionaries in the state and the ruling party who continued singing the praises of the leader while privately keeping track of the direction of the wind before casting their choice.

Increasingly the division between Maguphiles and Maguphobes is surfacing, particularly among parliamentarians. We may be witnessing a beginning of realignment of forces. Popular perception tends to be cynical, justifiably so, for none of the emerging factions resonates with their interests and daily lives. Street wisdom has it that with the change of wind, opportunist politicians are positioning themselves to be on the right side (‘wanajiweka sawa’ as the street Swahili goes) of the new president.

Between February 27, 2021 when he was last seen in public and March 17 when Magufuli’s passing on was officially announced, President Magufuli disappeared from the public eye. He was not seen at public functions nor did he attend church services on three consecutive Sundays. Magufuli was a practising Catholic and a devout church-goer. He never missed the Sunday Mass nor did he let go the opportunity to make political speeches from the pulpit. This practice distinguished President Magufuli from his predecessors to whom mixing politics with religion was anathema. They had been brought up on the secular doctrine preached and practised by Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, who never stopped reiterating that religion was a private matter and the Tanzanian state was secular. During the two weeks Magufuli was not seen in public, the country was awash with rumours, speculation and stories spun by spin doctors on Magufuli’s health, the nature of his disease, and whether or not he was alive. Internal detractors and a section of the foreign Western press superficially reported and gleefully reiterated that Covid-19 had finally caught up with President Magufuli who was reputed to be a Covid denier. The then Vice-President Mama Samia Suluhu Hassan gave heart complications as the cause of the president’s death. It was known that the president had a pacemaker. It is not necessary for the purposes of this essay to establish what the cause of death of President Magufuli was. I do not intend to cloud my analysis by that debate.

President Magufuli leaves behind a controversial legacy. It would be intellectually futile to strike a strict balance between Maguphilia and Maguphobia. That is a lazy way of understanding a political phenomenon. Drawing up a balance sheet of the good and the bad is an accountant’s job not that of an intellectual analyst. Rather it is important to understand that Magufuli was a political phenomenon, not an individual. Magufuli was a local variant of populist political leaders who have emerged recently in a number of countries of the South. Brazil and India are obvious examples. Conditions were ripe for the emergence of demagogic politicians, partly as a backlash to neo-liberalism which wreaked havoc with the social fabric of the countries in the periphery and partly because of the resulting polarisation, inequalities and impoverishment of the working people and middle classes. Disarmed, disillusioned and stripped of all hope, masses yearned for a messiah. Populists presented themselves as such deliverers. The masses in Tanzania found themselves in this state when Magufuli appeared.

Populist rhetoric varies from country to country but invariably it feeds on heightening racial, religious and gender differences and exploits popular prejudices. The Magufuli phenomenon was not a deus ex machina. To understand it we must locate it in the history and politics of the country and come up with a correct characterisation. I characterise the Magufuli phenomenon as messianic Bonapartism. Before we dwell further on this, let me say a couple of things about Bonapartism as a political phenomenon.

Bonapartism

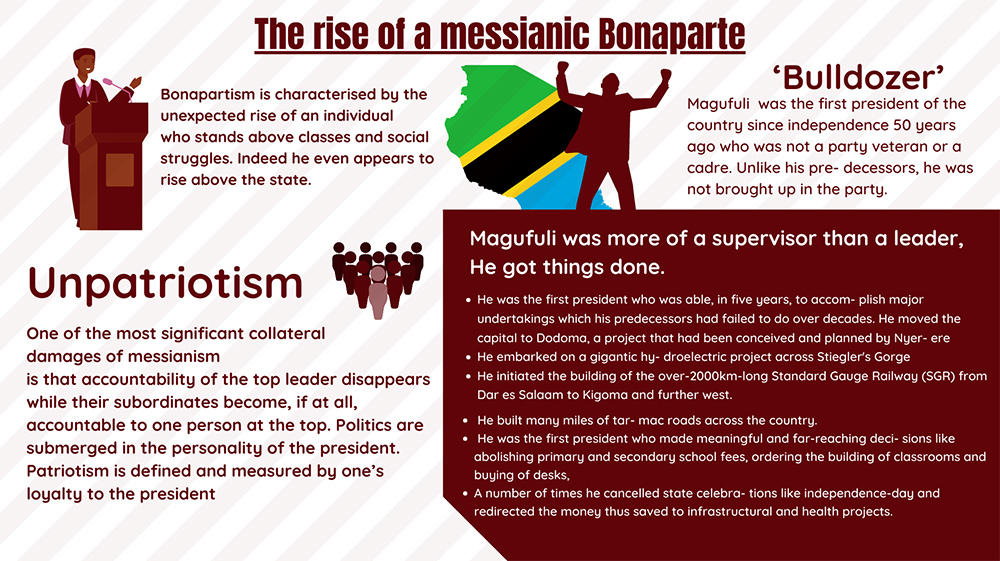

When classes are weak or have been disarmed ideologically and organisationally over a generation, politics suffer from Bonapartist effects. Bonapartism can take different forms depending on the concrete situation. Quickly, we may identify the two most relevant to us – militarist and messianic. Tanzania has been saved of the former for reasons which will become clear in the course of this essay. In the late president we witnessed the latter.

Bonapartism is characterised by the unexpected rise of an individual who stands above classes and social struggles. Indeed he even appears to rise above the state. The famous phrase attributed to Louis XIV ‘l’etat, c’est moi’, ‘I’m the state’ sums it all. Bonapartism has arisen in historical situations where the struggling classes have either exhausted themselves and there is an apparent vacuum in the body politic or the rein of the previous ruler has been so laissez-faire that ‘law and order’ has broken down. The Bonaparte legitimises his crassly high-handed actions to return the country to order and to rein in fighting factions in which everyone is for themselves and the devil takes the hindmost. Liberal institutions of ‘bourgeois’ democracy such as parliament and judiciary are either set aside (a fascist option) or emaciated of their content (neo-fascist authoritarianism). They exist in name only, but go through the rituals of elections, law-making and ‘judicial decision’ making, which means little in practice.

When classes are weak or have been disarmed ideologically and organisationally over a generation, politics suffer from Bonapartist effects

Unlike much of the rest of Africa, Tanzania can justifiably boast of a relatively stable and peaceful polity as well as smooth succession from one administration to another. Julius Nyerere, the founding president, ruled for nearly quarter of a century followed by three presidents, each one of whom was in power for ten years, that is, two terms of five years, the term limit prescribed by the Constitution of the United Republic of Tanzania, 1977. President Magufuli had just entered his second term after the general election of October 2020 when he met his death.

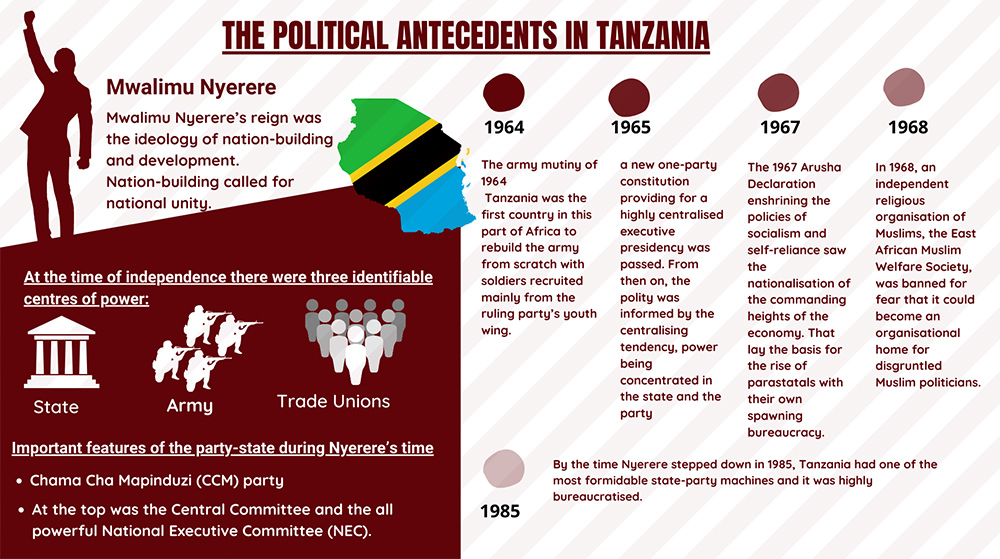

The political antecedents

The driving force during Mwalimu Nyerere’s reign was the ideology of nation-building and development. Nation-building called for national unity. Nyerere was preoccupied by national unity and as a result he reigned in centrifugal forces. At the time of independence there were three identifiable centres of power: the army, trade unions and the state. The army mutiny of 1964 and the alleged attempt by some trade unionists to make common cause with the mutineers drew home the point that all was not well and Nyerere’s national project was tottering. The mutiny became the occasion to dismantle the colonial army, ban independent trade unions and abolish the multi-party system. Opposition parties then were miniscule without much support but they had the potential to derail the national project, as Nyerere saw it. Tanzania was the first country in this part of Africa to rebuild the army from scratch with soldiers recruited mainly from the ruling party’s youth wing.

In 1965 a new one-party constitution providing for a highly centralised executive presidency was passed. From then on, the polity was informed by the centralising tendency, power being concentrated in the state and the party. In 1968, an independent religious organisation of Muslims, the East African Muslim Welfare Society, was banned for fear that it could become an organisational home for disgruntled Muslim politicians. The 1967 Arusha Declaration enshrining the policies of socialism and self-reliance saw the nationalisation of the commanding heights of the economy. That lay the basis for the rise of parastatals with their own spawning bureaucracy. Over a period of next ten years, relatively independent co-operatives were abolished and replaced by crop authorities. Independent student, youth, and women’s organisations were all brought under the wing of the party. Thus the proto-ruling class which could be described as a bureaucratic bourgeoisie or state bourgeoisie established its ideological and organisational hegemony. By the time Nyerere stepped down in 1985, Tanzania had one of the most formidable state-party machines and it was highly bureaucratised.

Four important features of the party-state during Nyerere’s time must be highlighted. One, the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party did function. Its organs had foundations at grassroots level in villages and streets. The party operated through its various organs such as party branches, ten-cell organs and similar organs, at district, regional and national level. At the top was the Central Committee and the all-powerful National Executive Committee (NEC). These organs met regularly and transmitted their resolutions and proceedings to higher levels. Two, the army was integrated in the party structure. It constituted a region which sent delegates to the NEC and the Congress, just as other regions did. Three, the party had a clearly spelt out philosophy and ideology which became the basis for developing its programmes and manifestos. Consequently, there was an ideology and a structure around which members could rally and participate in decision-making. Fourthly, as a result of these factors, political factions with a clear ideology and politics could not easily crystallise in or outside the party. If factions did emerge, they were temporary and issue-oriented. It was difficult for them to have medium or long-term political ambitions. The only group which did function as a faction and began to flex its muscles in the last five years of Nyerere’s rule was from Zanzibar. The succession saga within the party following Nyerere’s announcement that he was stepping down was actually led by Zanzibaris to which a few mainlanders aligned. To Nyerere’s surprise, the Zanzibari CCM faction proved to be so formidable that it managed to overturn Nyerere’s preferred choice to succeed him.

Magufuli was a local variant of populist political leaders who have emerged recently in a number of countries of the South. Brazil and India are obvious examples. Conditions were ripe for the emergence of demagogic politicians, partly as a backlash to neo-liberalism which wreaked havoc with the social fabric of the countries in the periphery and partly because of the resulting polarisation, inequalities and impoverishment of the working people and middle classes

In sum, although state structures of checks and balances were compromised during Nyerere’s time, the party did act as a check on top leaders providing a platform for relatively free discussions and debates within the party. Throughout this period, the independence of the judiciary was respected even though the judiciary could not play a very active role because, one, the constitution did not have a bill of rights against which the performance and accountability of the state organs and officials could be measured and, two, the law tended to be very widely worded, giving the bureaucracy unfettered discretion. These powers were often abused but grievous abuses were relatively rare and, if and when discovered, legal action was taken against the perpetrators. While Nyerere’s regime could arguably be described as authoritarian it certainly could not be labelled fascist in any sense of the word. When some overzealous youth wingers once described Nyerere as a ‘fascist’, Nyerere is said to have quipped: ‘What would they say if they saw a real one!’

The next ten years under President Ali Hassan Mwinyi saw the first, albeit hesitant, steps on the road to neo-liberalisation. It was during Mwinyi’s term that the leadership code which prevented state and party leaders from using their political office to accumulate personal wealth was lifted. There were also signs of factional struggles within the party but interestingly it was once again the coherent Zanzibar faction which mainlander CCM leaders with presidential ambitions had to attach themselves. Nonetheless, it was on Zanzibar issues – Zanzibar’s membership of the Organisation of Islamic Conference on its own and Parliament adopting a resolution to form a Tanganyika Government thus changing the union structure from two to three governments – that matters came to a head. Nyerere was still around. He managed to salvage the boat. The boat rocked but did not sink.

The next president, Benjamin Mkapa, was the first to be elected in a multi-party election, scoring a majority vote of only 62 per cent, demonstrating that the electorate was getting exhausted with CCM’s scandals and over-bearing bureaucracy. Mkapa, who served as president from 1995 to 2005, can easily be described as the father of neo-liberalism in Tanzania. He privatised national assets, including the national state bank, and steam-rolled through Parliament the mining law, opening up that important sector to rapacious foreign investment. However, he took a leaf from Nyerere’s book by adhering to party protocols and ensuring that the party organs met regularly and that there was a semblance of debate in the top party organs. During his term the judiciary became more active as a bill of rights had been inserted in the constitution in 1984.

By the end of Mkapa rule, Tanzania was a full-blown neo-liberal state. The hardest-hit victims of neo-liberalisation, as elsewhere, were the working people, in both urban and rural areas. As cost-sharing in education and health took hold and various subsidies were removed, the component of social wage from the livelihoods of working people disappeared, exposing them to the full rigour of the so-called free market. Even lower middle classes suffered. If Tanzania was spared of bread riots, it was because of the lingering ideological and organisational hegemony of the state-party over the working people.

Finding a successor to Mkapa proved to be contentious. Jakaya Kikwete and his friend Edward Lowassa, the party’s two leading cadres, had built a strong base in the party’s youth wing. They had waited in the wings to bid for the presidency at the opportune time. Through fair and foul means, aided by some manipulation of party rules by the then party chairman Mkapa, the Kikwete-Lowassa duo managed to keep out another strong contender, Salim Ahmed Salim. Kikwete got the party’s nomination, subsequently winning the presidency with a handsome majority. He lost no time in making his friend Lowassa his Prime Minister and one of their businessman friends – who was widely believed to play kingmaker behind the scenes – treasurer of the party. Eventually, the two friends fell out and Lowassa had to resign as Prime Minister. Be that as it may, the party had become fractionalised and mired in factional struggles. With no coherent ideology like the Arusha Declaration, the factions were not held together by any ideology or political programme but by sheer ambition to power and through power the ability to access the state largesse.

The ten years of Kikwete rule were one of the most laissez-faire periods in the country’s history. The neo-liberal chickens came home to roost. Scandals abounded, there was unchecked embezzlement of public funds, some politicians in collusion with businessmen went on an accumulation spree, corruption mounted. The party was side-lined. Kikwete did not have purchase on party meetings. The party and the government lost any semblance of coherence. The check-and-balance machinery broke down. Policymaking was erratic. Donors ruled the roost. To be sure, in this climate civil society elite and opposition parties enjoyed a measure of freedom which they had not experienced before but all that was at the expense of the masses who continued to sink deeper and deeper into poverty and hopelessness. The party lost credibility, so much so that when the time came for general elections it could not be sure of getting elected. Day by day, the opposition gained in popularity as it exposed the scandals and corruption of CCM politicians.

Unlike much of the rest of Africa, Tanzania can justifiably boast of a relatively stable and peaceful polity as well as smooth succession from one administration to another

Within the party, the person believed to be the strongest contender for presidency was Edward Lowassa. He had both political and financial clout but no purchase on political probity. He had cleverly put in place his people in vital party organs. Succession to Kikwete was ridden with factional struggles, so much so that when finally Lowassa lost out on nomination in the Central Committee, his faction in the Committee came out openly questioning the Central Committee’s decision.

As we have seen, the ruling party and its leaders had been so much maligned and marred by allegations of corruption that it had to nominate for the presidency a person who was not identifiable with the party and its heavyweights, a relatively clean person. That person was John Magufuli, until then a non-entity. In the elections, Magufuli got the lowest vote ever (58 per cent). Lowassa, having moved to the opposition, scored nearly 40 per cent. The opposition also won a significant number of seats in Parliament. As we shall see, Magufuli never forgave the opposition for their relative success.

The rise of a messianic Bonaparte

Thus were created almost textbook conditions for the rise of a Bonaparte, in this case, a messianic Bonaparte. By the time of the fifth president, the post-Nyerere presidents had abandoned the country’s cementing ideology, the Arusha Declaration. What was left of it was smashed to smithereens by the onslaught of neo-liberalism. The ideological vacuum thus created was filled with narrow nationalism and religious dogmas including religious salutations at political meetings and rallies in what was constitutionally a secular state.

The messianic variant of civilian Bonapartism best describes the Magufuli phenomenon. Messianic Bonapartism rules by fiat of the leader. It legitimises its rule not only by material measures in the interest of the down-trodden or oppressed (called wanyonge in Tanzania) but also by metaphysical appeals. The late President Magufuli used both in good measure. One of the most significant collateral damages of messianism is that accountability of the top leader disappears while their subordinates become, if at all, accountable to one person at the top. Politics are submerged in the personality of the president. Patriotism is defined and measured by one’s loyalty to the president. Any critique of the president is labelled unpatriotic or anti-national, the term widely used by Hindutva BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) in India.

Messianic Bonapartism shares some characteristics of the absolute monarchies of Europe. Absolute monarchs derived their legitimacy and authority from God, not from the people. And so-called good absolute monarchs were those who bestowed their largesse on their subjects. President Magufuli did not flinch in giving cash gifts to well-performing functionaries or leading an on-the-spot collection of funds for a complaining widow or a mama Ntilie. Such publicity stunts no doubt endeared the president to the masses, notwithstanding the fact that the impact of these acts was fleeting.

On many levels Magufuli scored a first in the political history of the country. He was the first president of the country since independence 50 years ago who was not a party veteran or a cadre. Unlike his predecessors, he was not brought up in the party. He was nowhere close to the first or second-generation nationalists. In his ministerial portfolios under the third president, Mkapa, and later under the fourth president, Kikwete, he was better known for his close supervision of infrastructure projects than for his political acumen or ideological leanings. He got things done, which earned him the nickname ‘bulldozer’. He was more of a supervisor than a leader. As a president, he never travelled outside the country except to nearby African countries. He did not attend a single United Nations General Assembly or an African Union Summit. He had little appreciation of international geopolitics. Although described as a Pan-Africanist after his death, he showed little understanding of the history or politics of Pan-Africanism. He saw regional organisations like the East African Community (EAC) or Southern African Development Community (SADC) as vehicles to enhance Tanzania’s trade and economic benefits rather than as the political building blocks of Pan-Africanism. Although he rhetorically used the term ubeberu (imperialism), it is doubtful if he ever understood it as a system. He hardly ever talked about ubepari (capitalism) or for that matter ujamaa, socialism. His refrain and rhetoric was maendeleo (development), kutanguliza Mungu (putting God first) and uzalendo (patriotism). For him, ‘development’ was non-partisan; ‘development’ was above politics, above ideology and above all-isms.

He was the first president who was able, in five years, to accomplish major undertakings which his predecessors had failed to do over decades. He moved the capital to Dodoma, a project that had been conceived and planned by Nyerere. He embarked on a gigantic hydroelectric project across Stigler’s Gorge. He initiated the building of the over-2000km-long Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) from Dar es Salaam to Mwanza and further west. He built many miles of tarmac roads across the country. He would invariably quote a string of statistics from memory of the length of roads built, the number of dispensaries, hospitals, schools and factories constructed under him. Whether these figures represented the whole truth on the ground, no one could tell, and those who could kept quiet for fear of contradicting the all-powerful and unpredictable leader. As a matter of fact, during Magufuli’s time the Statistics Act of 2015 was amended to make it a crime punishable by a fine of ten million shillings or three years imprisonment or both ‘to disseminate or otherwise communicate to the public any statistical information which is intended to invalidate, distort or discredit official statistics’ (section 24B). A year later the amendment was repealed following pressure from local NGOs but not until the World Bank issued a statement showing its concern with the amendments and ending with a threat to withdraw its financial support to the strengthening of the national statistics system.

While Nyerere’s regime could arguably be described as authoritarian it certainly could not be labelled fascist in any sense of the word. When some overzealous youth wingers once described Nyerere as a ‘fascist’, Nyerere is said to have quipped: ‘What would they say if they saw a real one

While some of the mega-projects (like the SGR) undoubtedly made developmental sense, others were controversial given their possible medium and long-term ecological effects. The Stigler’s Gorge project and others (like buying eight airbuses and the Tanzanite bridge across the sea) could very well prove to be white elephants. While Magufuli lived, no one dared to challenge or contradict him. One consulting geologist from the University of Dar es Salaam who gave an adverse report on the feasibility of the Stigler’s Gorge project was roundly condemned by the president in public before his peers for being unpatriotic.

He was the first president who made meaningful and far-reaching decisions like abolishing primary and secondary school fees, ordering the building of classrooms and buying of desks, extending health insurance coverage at a cheap premium to almost one-third of the population, issuing street vendors and kiosk owners with identity cards at twenty thousand Tanzanian shillings which would legitimise their occupation and free them from constant harassment by city police and militia. A number of times he cancelled state celebrations like independence day and redirected the money thus saved to infrastructural and health projects. These and other populist moves, some impactful and others inflated out of proportion, endeared him to wanyonge and earned him the title ‘people’s president’, ‘man of the people’ and many other accolades generously bestowed on him by courtiers and praise singers.

Magufuli’s populist measures were not without contradictions. For instance, he barred pregnant school girls from education on the grounds of patriarchal morality which typically blames the victim. Use of misogynistic language was legendary with him. He unabashedly made remarks on the skin colour and figures of young female functionaries in his government. Yet hardly any local gender lobby could dare call him out. While he made primary and secondary education ‘free’, the loan instalment payments by university graduates was doubled, leaving little from their salaries for their upkeep.

He had little respect for the constitution or law. He did not even pay lip service to the rule of law and breached law and the constitution at will. He fired and humiliated senior civil servants in public meetings contrary to public service regulations and without proper investigation of their alleged misdeeds. While this to some extent restored discipline in the civil service, it was a discipline born of fear resulting in his ministers and civil servants shying away from making decisions.

During President Magufuli’s reign some of the most draconian pieces of legislation were passed, propelled by his compliant Attorney General. Public interest litigation (founded on article 26 of the country’s Constitution), under which a number of constitutional petitions were filed challenging some laws and Magufuli’s public appointments, was abolished. A few vocal lawyers conducting such cases were taken before the Advocates Committee for disciplinary action. One of them, who had appeared in a case in which the credentials of the Attorney General himself were questioned, was struck off the roll of advocates. At the time of writing her appeal is pending before the High Court.

The list of unbailable offences under the notorious Money Laundering Act was extended to cover even such offences as tax evasion and use of illegal fishing nets. The law was generously used by the prosecution to incarcerate critical journalists and commentators. A few such cases were sufficient to strike fear in the rest, including critical intellectuals and academics. Once famous as a site of critical debates and discussions, the University of Dar es Salaam became an intellectual desert with its faculty tight-lipped in the face of momentous happenings outside the campus. To be fair, Magufuli could not be solely blamed for this as the trend had already set in in the previous decade. One of the major collateral damages of neo-liberalisation of the university and marketisation of its scholars was the emaciation of the critical intellectual content of university life. But that is a subject on its own and is best left for another day.

Under Magufuli’s presidency, the executive branch of the government became predominant riding rough-shod over other branches. During his presidency, it would require a leap of imagination to believe that the country had separation of powers. Mundane state functions like swearing-in ceremonies became grand functions at the state house with live TV coverage. Invariably, the Speaker of the National Assembly, the Chief Justice, commanders of the army and the police would be present seated in the front row with all their regalia. During such functions, which were essentially executive functions, the Speaker and Chief Justice would be invited to speak assuring the president of their loyalty and re-iterating their admiration for him. His speech would come at the end. In a long-winded rambling monologue, he would harangue, humiliate and even reprimand his ministers and other public officials. The president would often give thinly veiled instructions to the head of the judiciary and the legislature. The speech would end with his oft-repeated refrain that he would not flinch from speaking the truth for those who tell the truth are the beloved of God.

Under President Magufuli’s watch the country for the first time witnessed disappearances and kidnappings whose perpetrators remain unknown to this day. The perpetrators, we are told, were ‘watu wasiojulikana’ (unknown people). During his reign a wealthy businessman was mysteriously kidnapped and as mysteriously reappeared after 10 days. To this day it is not known what the motive was, who did it and what was the deal between the perpetrators and the victim’s wealthy family that led to his release. The businessman incredibly claimed a year later that no ransom money had been paid (https://www.bbc.com/ news/world-africa-50235322). An outspoken, high-profile, if somewhat erratic, leader of the opposition party was shot at in broad daylight by the occupants of a trailing land cruiser. Sixteen bullets were pumped into his body. Thankfully he survived, after dozens of surgeries performed on him in a foreign country, but the agony and the traumatic experience that he and his family and his admirers went through was inhuman and immeasurable. To date the perpetrators have not been arrested or sent before a court of law, nor does anyone know if the police are continuing the investigation or if the file has been conveniently closed.

The driving force during Mwalimu Nyerere’s reign was the ideology of nation-building and development. Nation-building called for national unity. Nyerere was preoccupied with national unity and as a result, he reigned in centrifugal forces

Soon after coming to power on a slim majority, by Tanzanian standards, of 58 per cent President Magufuli lost no time in coming down heavily on opposition parties. Political rallies were banned, opposition leaders were harassed, and slapped with all kinds of charges which kept them in court or prisons most of the time. Civil society organisations and NGOs fared no better. Funded by foreign agencies, some of them dubious, and having no constituency or agenda of their own, NGOs were most vulnerable. Extreme controls were imposed on them. Some of them found their bank accounts closed while others were subjected to all kinds of demands from revenue authorities.

As might be expected, print and electronic media bore the brunt of repression. While public media joined the praise-singing choir, private media too fell in line to protect their businesses and profits. Fearing closure or being slapped with heavy fines by the regulatory agency (TCRA) for smallest of infractions (which were not unknown), the media avoided controversial stories and investigative reporting. A couple of critical newspapers and online TV channels were either banned or starved of advertisements. They went under.

Ironically while the mainstream media was undergoing censure, a mysterious media mini-tycoon emerged on the scene like a phoenix. He owned a couple of newspapers and TV Online (an Online TV channel). His newspapers defamed prominent people, even party stalwarts, without let or hindrance. He abused and poured verbal venom on Magufuli’s critics and perceived opponents and enemies. He had no respect for professionalism or ethics. No disciplinary action has ever been taken against him either by regulatory bodies or media watchdogs.

Arguably the measure which was most important in making Magufuli known on the continent was his bold taking on of the multinational gold company Barrick Gold. And he did it in his own spectacular fashion. He stopped containers full of mineral sand to be exported by Acacia, a subsidiary of Barrick, for smelting. He formed a local team of experts to investigate the mineral content of the sand. Simultaneously, the Tanzania Revenue Authority slapped on it a huge bill of unpaid taxes amounting to USD190 billion. As expected, the expert team found that the sand contained a variety of minerals costing billions of shillings. The long and short of the story is that Barrick Gold had to send its chief executives to Tanzania to negotiate with the government, bypassing the Acacia management. Eventually, the parties struck a deal under which Barrick would pay USD300 million in settlement of the tax dispute and give Tanzania a 16 per cent stake in a new company, Twiga Minerals, which would operate Barrick’s three mines. Meanwhile, the ban on export of mineral sand was lifted. Details and the small print of the agreement were never made public. It is not clear if the promises made have been fulfilled.

In the same vein, a progressive piece of legislation called Natural Wealth and Resources (Permanent Sovereignty) Act was passed in 2017. While the law recognises the sovereign ownership of the people of natural resources, they are legally vested in the president who holds the same in trust. Most of its provisions, including this one, are really hortatory in that they cannot be easily enforced in a court of law. Nonetheless, the law did send a strong message that at least in theory the Tanzanian government would not tolerate any exploitation of its natural resources which had no benefit to the people of Tanzania. One provision which forbade any international agreement from providing for dispute settlement by outside bodies could be considered a great advance since most of these agreements invariably provide for international arbitration of disputes. Research has to be done to establish if this provision has been observed in practice. My hunch is that it has not.

The president also boldly moved against grand corruption. A number of high-profile, and hitherto untouchable, business people perceived to be corrupt were charged with unbailable offences. A few bought back their freedom through plea-bargaining; some are still rotting in jail. The former Vice-President of Acacia Deo Mwanyika was charged with money laundering for alleged tax evasion soon after retirement from the company. Eventually, he bought his freedom by way of a plea-bargaining agreement coughing up millions of shillings. (indeed many others charged similarly had to agree to pay handsome sums of money to get back their freedom.) Ironically, he was nominated by Magufuli’s party to stand for Parliament in the 2020 elections which he duly won. A well-known businessman who had been charged under the money laundering law for allegedly avoiding taxes died in remand custody.

In the 2020 general election Magufuli won by a landslide, getting an unprecedented 84 per cent while the ruling party won all parliamentary seats except a couple. Opposition parties cried foul but theirs was a voice in the wilderness. For the first time since the general elections began in the country in 1965, no election petitions were filed. It was a telling comment on the 2020 General Elections under President Magufuli’s watch. It was also a veiled pointer to the loss of people’s trust in the impartiality of the judiciary.

Within two or so years of Magufuli’s rule the civil and political space virtually disappeared. Selected disappearances, court cases against perceived opponents and closure or fining of media – both print and electronic – instilled fear, uncertainty and hopelessness even in outspoken academic critics. Magufuli shrewdly dangled carrots in front of academics by appointing a significant number of professors and PhDs to his cabinet and top public service positions thus denuding the university of its most senior faculty. The remaining joined the queue hoping to be picked up in the next round of presidential appointments.

The country had never before experienced such an intense perception of repression. Critics were subdued. Some leading opposition politicians were ‘bought’ off with political positions. Overnight they crossed the aisle becoming flag-waving members of the ruling party. Meanwhile, the populist rhetoric coupled with promises of beneficial material improvement for the wanyonge – free education, health insurance, relative discipline in delivery of public services and well-publicised action against notorious businesspeople for corruption, tax evasion, drug business etc – garnered support of the masses behind the president. The president’s unrelenting industrialisation drive, albeit unplanned and incoherent, gave jobless youth the hope of employment. In the event, whatever new industrial plants were put up they made little dent on unemployment figures. In itself the idea of industrialisation had a lot to commend it but for it to make developmental sense it had to be coherent and consistent with a broad vision of building a nationally integrated economy in which industry and agriculture would be mutually reinforcing. The president had no such vision and it is doubtful if he sought any advice or accepted it if given.

The president also became the chairman of the party, in terms of the convention established by the first phase government. Nyerere believed, not without reason, that the Tanzanian polity was not ready for the separation of the state president and the party chairman. The party was brought up and bred on centralisation of power. Under Magufuli’s chairmanship, party organs like the Central Committee and NEC were slimmed down in terms of numbers and filled with loyalists. The old guard of the party was weeded out. Two former Secretary Generals of the party and the foreign minister in Kikwete’s government with presidential ambitions were hounded, defamed and relentlessly humiliated in the media owned by the new kid on the block (see above). No action was taken against the mini media tycoon. Instead, the victims of his defamation campaign were subjected to disciplinary measures. One was reprimanded, another was suspended and put under watch while the former foreign minister was expelled.

Messianic Bonapartism shares some characteristics of the absolute monarchies of Europe. Absolute monarchs derived their legitimacy and authority from God, not from the people. And so-called good absolute monarchs were those who bestowed their largesse on their subjects.

Eventually, all but the latter asked for forgiveness and were duly forgiven. A similar dose of medicine was administered on one of the very vocal cadres of CCM who had campaigned vigorously for Magufuli in the 2015 election. He was appointed minister for information in the Magufuli cabinet. He dared to cross swords with one of Magufuli’s favourite regional commissioners which earned him a revocation of his appointment as a minister. When he tried to hold a press conference to explain his side of the story at a city hotel, he was confronted by a plain-clothes pistol-wielding person who forced him back into his car. To this day no one has been held accountable for that roguish behaviour. Eventually he too asked for forgiveness and was duly forgiven.

The new chairman of the party appointed a young person from the University of Dar es Salaam with progressive credentials as Secretary-General of the party. Another young person with no political or ideological credentials to speak of except vituperous outpourings became the ideology and publicity secretary of the party. None of them had an independent base either in the party or outside. They became the public image of the party in the shadow of the chairman to whom they were eternally beholden.

The passing of the president

The framers of 1977 Constitution (as amended) wisely provided for the contingency of the death of an incumbent president. In case of such eventuality the vice-president would take over for the remaining the term of the deceased president. This provision was not well known even to constitutional lawyers and had certainly not featured in public discussions on the constitution. This was so partly because there had never been such an occurrence but mainly because this provision was new, having been introduced in one of a spate of constitutional amendments following the introduction of multi-party in 1992. In the Eighth Constitutional Amendment, the framers borrowed the system of a running-mate from the United States. Together with this, the framers took over almost lock, stock and barrel the American provision on succession in case of the death of an incumbent president (25th Amendment to the US Constitution). Article 37(5) of the 1977 Constitution stipulated that in case of, among other things, the death of the incumbent, the vice-president should be sworn in to be the president.

After the announcement of the death of the president it took almost 60 hours before the vice-president was sworn in.2 A few legal commentators opined that there was a lacuna (gap) in the constitution which did not provide the timeframe within which the vice-president had to be sworn in. One legal expert who has attained a kind of celebrity status for conducting public interest litigation even opined that it would be imprudent to swear in the succeeding president while the body of the late president had not yet been interred. One does not have to be a constitutional expert to read the constitution in context to conclude that the successor has to be sworn in immediately, that in fact there is no lacuna in the constitution. Under Tanzania’s Constitution the president is the commander in chief of the armed forces with powers to declare war and make peace, with powers to declare state of emergency etc. The presidency therefore cannot remain vacant for any length of time. The practice in the US, from where article 37(5) of the Tanzanian Constitution was lifted, has been to swear in the vice-president to become president immediately on the confirmation of the death of the incumbent president. When John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963 in the city of Dallas, Lyndon B. Johnson, his vice-president, was sworn in within two hours onboard Air Force One while it was still parked on the runway. In the event, to the relief of many, the constitution prevailed. It is not clear which superior force intervened in favour of the constitution. So far, the transition has gone smoothly.

Glimpses into the future

It is too early to say the direction that the new regime will take under president Samia Suluhu Hassan. To be sure, it is likely to be a little more liberal politically and economically and a little less heavy on invoking rhetorical invectives against western governments. In changing the symbolic salutation from religious to secular, the president will probably adhere to the secular tradition of the country. She is likely to open up to the outside world. The extent of opening up will determine whether her government draws in the laissez-faire elements of the fourth phase government or remains within the parameters of national interest. All in all, the party and the government which she now heads is likely to continue on the path of neo-liberalism. Thus the stark choice in the immediate and medium-term future is not so much between nationalism and neo-liberalism but rather between rampant and regulated neo-liberalism.

Whether or not and how far the new president opens up the civil space will also determine how far the working people are able to organise themselves openly to defend their interests. There are disturbing signs that opportunist politicians, businessmen and IFIs (International Financial Institutions) are getting too close to the president. If they prevail, the neo-liberal path will consolidate itself. There is a fear among more conscious elements that some of the worst features of neo-liberalism – rampant pillage of natural resources, reaping of monopoly super-profits at the expense of the working people, land grabbing resulting in eviction of smallholders, further exacerbation of social inequalities and mass misery– may once again reappear with a vengeance. In which case, whatever goodwill the president may have generated will quickly evaporate.

One major lesson to draw from the Magufuli phenomenon is that our polities in the periphery remain fragile and masses disorganised. Therefore our polities are vulnerable and amenable to the rise of narrow nationalists and populists on the one hand, and rampant neo-liberals on the other. Under the circumstances, organisation-building remains foremost on the working peoples’ agenda. The politics of class struggle have to transit from spontaneity to organisation just as committed left intellectuals have to transit from being public to organic intellectuals.

Ultimately the working people have to depend on themselves rather than wait for a messiah to deliver them. Hopefully the Magufuli phenomenon would have taught progressive African intellectuals to distinguish between rhetorical anti-imperialism and systemic understanding of the global capitalist-imperialist system; between populist demagogues and popular democrats; between mass political line and mass evangelism; and between a protracted struggle of the working people for liberation and emancipation from below and short-cut measures to development and promises of deliverance from above.

–

This article was first published by CODESRIA in the Codesria Bulletin online, N°13, June 2021.