The return to multipartyism in the early 1990s and the implementation of the 2010 constitution were seen by many as seminal moments in the democratisation of Kenya. However, in truth, they merely masked what essentially remains an unchanged bureaucratic-security state dating back to the colonial era that is today reproducing itself at the county level. The continuity and longevity of this state has chiefly been the product of an ideology of law and order created to protect the class and commercial interests of an African colonial elite.

For the colonial enterprise in Kenya to succeed, it needed local allies who would bring existing economic and political institutions into the newly created colonial order. However, this arrangement, which privileged the small white settler community, irrevocably corrupted and even usurped indigenous African authority and generated a collaborating class of African big men whose loyalty was no longer to kinship networks and ties but to the newly established colonial government.

Over time, the newfangled chiefly power and leadership of men like Koinange wa Mbiyu, Karuri wa Gakure, Njiiri wa Karanja, Mumia of Wanga, Ole Murumbi of the Maasai, Owuor Kere of Nyakach, Kinyanjui wa Gathirimu, Muhoho wa Gathecha, Michuki wa Kagwi and Ogola Ayieke resulted in a ready-made socioeconomic and political class to whom independence and state power could be entrusted in 1963.

It is therefore no coincidence that many of the politicians and senior government administrators who have dominated the top ranks of government and the civil service in post-colonial Kenya were scions of this class. These include the recently deceased Simeon Nyachae (son of Chief Musa Nyandusi), Joab Omino, the Mwendwa brothers (Eliud Ngala Mwendwa, who served as the Minister of Labour in Jomo Kenyatta’s cabinet, and Kitili Mwendwa, the first African Chief Justice of Kenya), John Njoroge Michuki, Kariuki wa Njiiri, Peter Mbiyu Koinange (son of Chief Koinange who also served as a powerful Kenyatta minister).

Although he was not himself the scion of a colonial-era chief, Jomo Kenyattta wisely married into chief Koinange wa Mbiyu’s family and, later, into that of Chief Muhoho wa Gathecha, thus founding one of Kenya’s foremost and lasting political dynasties. His immediate successor, Daniel arap Moi, established his own dynasty that is showing a similar political tenacity.

The return to multipartyism in the early 1990s and the implementation of the 2010 constitution were seen by many as seminal moments in the democratisation of Kenya. However, in truth, they merely masked what essentially remains an unchanged bureaucratic-security state dating back to the colonial era that is today reproducing itself at the county level

Jomo and the presidents who succeeded him have all sung the same refrain of law and order that was sang in colonial times. For this class of big men, political stability and the peaceful maintenance of the status quo has been the singular objective. Through a masterful stroke of political genius, Moi repackaged it into the populist appeal of his Nyayo philosophy of love, peace and unity. Mwai Kibaki, for his part, hinted at it when he reminded people that Kenya was a working nation and that there was nothing for free. At every stage of its evolution, the Kenyan state has had a steady hand at the helm ensuring the continuity of the ideology of order.

However, ensuring the survival of this vision amid the political reality of the Kenyan state with its veneer of democracy demands the suppression of all alternatives articulated and championed through political dissent. Beyond its preoccupation with the preservation of power, the ideology of order is thus also committed to protecting the Kenyan state and its brand of democracy from the people.

‘The danger to democracy is the people’

One of the colonial state’s greatest fears is the masses. Colonial authorities, and later, independent Kenya’s African ruling elite, were afraid the hordes of have-nots might rebel and challenge the politics of law and order as they had in 1952. Therefore, the imperative was to coopt, exclude or crush all dissenting voices in society. This is a task that the political heirs of the colonial state — led by Kenyatta and the scions of chiefly power such as his attorney general Charles Njonjo — fulfilled to the hilt.

Having already been recognised as the rallying political symbol through whom the hopes of the European community, London’s commercial interests and continued military presence, and the ideology of order could be secured, Kenyatta had his task already cut out for him on the eve of independence. He faced-off with the Kenya Land and Freedom Army — the Mau Mau — who sought to create an equitable society by any means, including violence. Unsurprisingly, early during Kenyatta’s tenure at the helm, much of the time was spent coaxing fighters to leave the forest and surrender their weapons.

One of the colonial state’s greatest fears is the masses. Colonial authorities, and later, independent Kenya’s African ruling elite, were afraid the hordes of have-nots might rebel and challenge the politics of law and order as they had in 1952

On the whole, Kenyatta attempted to temper the high expectations of ordinary Kenyans with his calls for Harambee (pooling together), pleas to forgive and forget the past and, consistent with the ideology of order which he understood only too well, entreating people to celebrate and embrace “uhuru na kazi” (“freedom and work”) — an appeal later echoed by Kibaki.

Toward the end of Kenyatta’s tenure, as his faculties were dulled by age, his ideological lieutenant, Njonjo, a chiefly big man in his own right, held guard against “dangerous agitators”. Njonjo openly threatened to jail the radical novelist Ngugi wa Thiong’o who had just penned his incendiary novel, Petals of Blood which both London and Nairobi feared would inspire a revolution. The palpable and shared crowd-phobia by the custodians of the ideology of order shows they understood that “the danger to democracy is the people”, who had to be thwarted at every turn and by every means available to the state.

Moral anarchy and the culture of impunity

The colonial state was built not through consensus as a democracy, but by decree. Not only did the colonial system corrupt African traditional authority and contribute to the destruction of African morality — thus creating moral anarchy — but it also sowed the seeds of a political culture of impunity. Indeed, the colonial state was itself a result of impunity.

Two of Kenya’s largest corruption scandals, Goldenberg and Anglo Leasing, were enabled by this culture of impunity. The Goldenberg scandal, which occurred between 1990 and 1993 under Moi’s imperial presidency, entailed the government paying Goldenberg International special compensation for fictional exports of gold and diamonds. The total cost of the scandal is unknown, but some estimates indicate that up to 10 per cent of Kenya’s GDP was lost.

Anglo Leasing, which occurred between 1997 and 2003, involved payments to a British company under the guise of investing to improve Kenyan security services, such as $36 million for new high-technology “tamper-proof passports”. However, the scandal also involved payments to other fictitious corporate entities that were paid to supply naval ships and forensic laboratories. The fact that this scandal straddles both the Moi and Kibaki administrations is quite telling. It shows that high-level corruption in the country is deeply entrenched in the bureaucracy and is, therefore, systemic or institutionalised. Alluding to this repugnant systemic morass of corruption, John Githongo, the former anti-corruption tsar and whistleblower who served in the first half of Kibaki’s first administration as the Governance and Ethics Permanent Secretary, sadly observed in a public personal statement on May 2, 2019 that:

“The Anglo Leasing model of misappropriation of resources from the Kenyan people has continued unabated since 2001. . . . Over the past six years in particular the plunder of public resources has accelerated to levels unprecedented in Kenyan history since independence. Increasingly the economic, political, social and very personal cost of this plunder by officials in positions of authority has been borne by the Kenyan people directly.”

The Uhuru Kenyatta government too has been rocked by several corruption scandals including the Eurobond scandal which entailed the mysterious disappearance of over $1 billion after Kenya issued its first sovereign bond in 2014. The amounts of money said to have gone missing under Uhuru Kenyatta are staggering. It is not surprising that skyrocketing corruption under President Kenyatta, the country’s fourth, dwarfs all previous corruption scandals.

Flagrant and rampant corruption in the post-independence era has surprised even Kenya’s erstwhile rulers. Reacting to Anglo Leasing, the biggest scandal of the Kibaki era, Sir Edward Clay, the then British High Commissioner to Kenya, lamented that top figures of the hegemonic regime were eating “like gluttons” and vomiting “all over our shoes”.

This “eating” culture at various levels of the bureaucracy and in the high echelons of government is mirrored throughout society. Corruption permeates Kenyan society because it is the sort of society that the predatory state has created. In 2015, exasperated by rampant corruption, Dr Willy Mutunga, then Kenya’s Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Kenya, concluded that Kenya had become a “bandit economy”. The respected and high-ranking jurist complained that corruption stretched from the very bottom to the very top of society. As an apparatus transforming society, the Kenyan predatory state has created a sukuma wiki bandit economy characterised by survival by any means necessary.

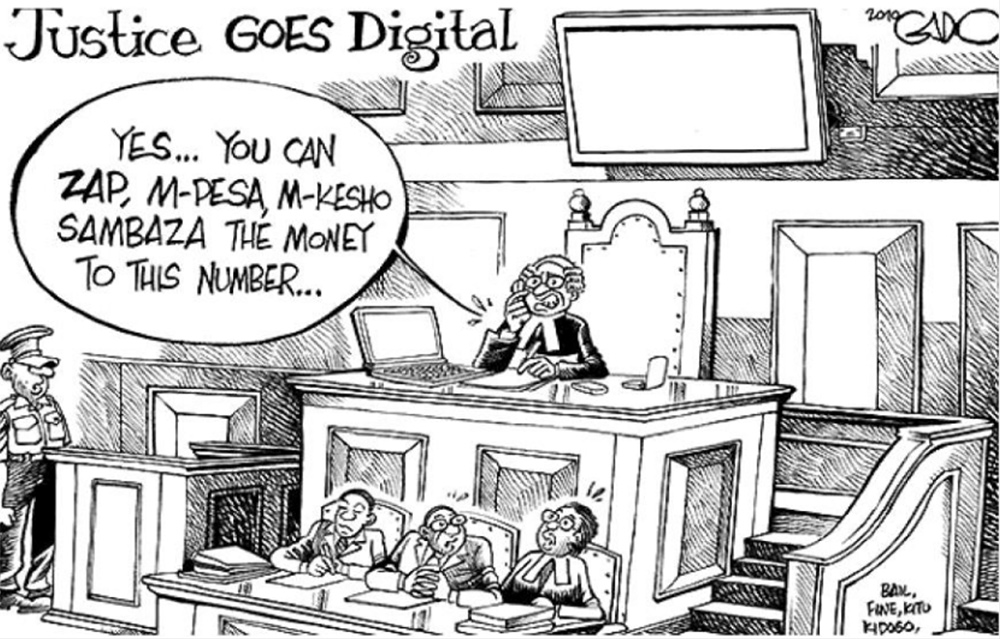

Indeed, corruption so permeates society that it scarcely leaves anyone untouched or unaffected. The unwritten code is expressed in the African proverb, “the goat eats where it is tethered”. It is, therefore, not surprising to find corruption and the trading of favours, bakshish, among lawmakers, among revenue collection officials, among parents, teachers and students in schools and universities, among doctors, nurses and staff in hospitals, in the corridors of justice among judges and magistrates and even in the so-called disciplined forces including the police.

The colonial state was built not through consensus as a democracy, but by decree. Not only did the colonial system corrupt African traditional authority and contribute to the destruction of African morality — thus creating moral anarchy — but it also sowed the seeds of a political culture of impunity. Indeed, the colonial state was itself a result of impunity.

The poor remuneration of public servants, a poor incentive system for hard and honest work (due to nepotism and ethnic discrimination) and socioeconomic frustrations caused by unemployment or underemployment, force ordinary citizens to resort to corruption. Working people, much like a tethered goat, tend to eat where they are “tethered”, or, put differently, use the nature of their work to look after themselves. Professional people, therefore, do not only find it necessary but also morally easy to exploit their professions or their workplace because of such tacit African cultural sanction of bakshish – acceptance of relatively small gifts or money in return for services rendered. In the meld of African traditional values and modernity in a society imbued by corruption, the line between gratitude and corruption is blurred.

In this way, therefore, the strategies adopted for material survival by school principals, the military, lawmakers, judges, magistrates, the police and other civil servants, people in the private sector, and even criminals, are not dissimilar from those used by leaders to accumulate power and wealth. Thus, the tempting image of innocent, by-standing masses, or viewing the Kenyan public as victims of grand corruption, is shattered. There is, therefore, no prospect of a united demand for clean government. It could even be said that very few Kenyans qualify to make such a demand.

In Kenya, the bribes collected go by many words: bakshish, chai (tea) or kitu kidogo (something small). In this sukuma wiki bandit economy characterised by predatoriness, survival is at any cost. Hence, the civil servant and other officials who are poorly remunerated, or simply harbour an insatiable greed for riches, make their living or build their fortunes off the people they serve rather than from their meagre salaries.

Even heads of public schools are known to charge exorbitant tuition and illegally admit students, while in hospitals, necessities like mattresses and bed sheets, even prescription drugs, are known to be sold-off by poorly paid staff. At times, members of the police force, politicians and other public authorities, are forced to collude with the criminal underworld. Facing harsh laws or the lynch mob, young criminals have no choice but to kill or be killed, unleashing a veritable balance of urban terror. This can also be interpreted as an unlawful effort at a re-distribution of the resources hoarded by the rich in society. In major cities, rural areas and townships, local people engage in all sorts of vandalism of public service installations and petty theft. In other more remote localities, traditional raiding or cattle rustling, for example in the North Rift region and the North Eastern Province, this survival-by-all-means bandit economy translates into a form of political action.

Culturally and structurally, therefore, both the state and Kenyan society have mutually transformed each other, producing a national psyche characterised by moral anarchy and primal greed; the state and society mutually reinforce each other in entrenching unabated, runaway corruption, a culture of impunity, and politics of (dis)order.

The twin tyranny of political tribalism

At the core of the bane of politics in post-independent Kenya is the twin tyranny of political tribalism. On the one hand is the tyranny of the masses, that is, the pressure that different ethnic groups — and seasonal and shifting ethnic-political alliances — place on their respective ethnic bigwigs. On the other is the tyranny of the ruling class that is responsible for the institutionalisation of grand malfeasance. These two tyrannies feed off each other and are, as such, inextricably connected.

With political consciousness and organisation restricted only within the bounds of discrete, administratively designated “ethnic regions” during the colonial era and well into the postcolonial period, wealthy politicians have acted as guardians or custodians of their respective ethnic groups to the exclusion of all others within the political context of perceived stiff competition for public goods or state power.

The masses, as ethnic political “patrons” — either pursuing their real or perceived pan-ethnic interests — neither have tribal innocence nor are they innocent of the endless accumulation and concentration of power in the hands of the political elite without accountability, and the perpetuation of corruption. After all, when they act, whether at the ballot box or when they defend their ethnic elite “clients” even when they are accused of grand corruption, they do so simply along ethnic lines.

Both in the colonial and postcolonial periods, therefore, ethnicity (political tribalism) acts as the main vehicle through which dominance and the preservation of power and resources are achieved. In turn, ethnic political elites are beholden to “their own”; they are expected by their respective ethnic groups to defend and expand real or perceived pan-ethnic interests and opportunities with regard to the modern economic, or civic public, sector.

This, then, is the first tyrannical twin of political tribalism. A classic case of the tail wagging the dog or, as E.S.A. Odhiambo puts it in The Political Economy of Kenya, the logic of patron-client relationships turned upside down. According to Odhiambo, political entrepreneurs:

“Came to the threshold of state power with a specific objective. The bottom line for all of them was that they had to ‘deliver the goods’. . . . To maintain and reproduce their bases of power, they had to recruit, sustain, and reward their followers from time to time. . . . The peasants have the latitude, at elections, to shift their patronage. The fascination with the fact that the Kenyan member of Parliament is vulnerable at election time should acknowledge the fact of peasant choice as well as the peasants’ success at insisting on accountability by the parliamentary representative to his constituents. Put more directly, the masses put the leaders on the run to the gates of Parliament. ‘They invaded the state with society at their heels rather than imposed it on the people. They were accountable to an elected democracy’.”

But at times, indeed, more often than not, and increasingly over the course of time, to do so – delivering public goods to sustain the support of their patrons, namely, their close individual supporters/enablers or cronies and tribes – politicians, as tribal clients, have no recourse but to seek to gain private capital out of the public domain. State coffers are, therefore, raided rather blatantly by the political elite in order to benefit their immediate and extended families (nepotism), ethnic communities (tribalism) and/or elite cronies and political allies.

This, then, is the second twin tyranny of political tribalism: rampant, massive and seemingly endemic institutionalised corruption unleashed on the nation by the political elite in their quest for the accumulation, concentration and perpetuation of power and (re)producing themselves. This is the conundrum of the twin tyranny of political tribalism. On the one hand, a collection of patron-tribes acting as rational actors exacting high expectations of public goods on their clients, their corresponding ethnic political elites. And on the other hand, insatiable politicians who exploit ethnicity and such tribal expectations and demands to profit by looting the public domain. There are, after all, no serious investigations into subsequent and ever increasing corruption scandals.

Tribal bigwigs are untouchable sacred cows even when implicated or involved in appalling corruption scandals. After all, they enjoy the unstinting support of their tribes who would rather be “eaten” by the hyena they think they know (a politician from their own ethnic group) than one they neither really know nor care to know (a politician from a different ethnic group).

It is not surprising, therefore, that when it comes to fighting corruption, Kenyans are rather resigned to their fate. Politics, for the most part, is viewed as an inherently flawed and dirty game; a rather cynical acceptance that ordinary citizens can do nothing about it except vote for political tribalism. This languid attitude ensures that, collectively, ordinary people are unsafe and are, more often than not, not at the table but, rather, on the menu. And so goes the vicious cycle, the Kenyan political circus window-dressed as a paragon of Western democracy in Africa although multiparty elections are largely nothing more than ethnic contests that take place every five years.

The Configuration of State Patronage / National Finance Grid (NFG)

The ideology of the propertied elite is thus shored up by the pervasive ideology of tribalism which defines the struggle and capture of state power. The corresponding democracy emanating from within such a political system is one in which the election-winning strategy is based purely on ethnic considerations. Political and economic competition in the context of tense inter-ethnic relations has a deleterious and blighting effect on a range of important institutions that generally give states their form, stability and longevity.

The highly ethnicised nature of Kenyan politics and the stultifying and stunting sway and monopoly of ethnic kingpins has historically created personality cults and hegemonic political dynasties that hark back to the very first collaborating class of African big men who were produced by the colonial order of the early 20th Century.

Culturally and structurally, therefore, both the state and Kenyan society have mutually transformed each other, producing a national psyche characterised by moral anarchy and primal greed

Having reproduced itself over the years, this political class has consolidated a hegemony that enables it to flaunt, subvert or circumvent institutions based on democratic values such as the constitution that guaranteesfreedom of expression, freedom of conscience, freedom of meeting, freedom of association, the rule of law; a free and independent judiciary; an independent election commission; public integrity and control bodies; and the civil service, among others.

But it is the generic political partyfounded on principles or championing social issues of concern and pursuing clear ideological positions that has, arguably, borne the brunt of dynastic and tribal politics. In the face of political tribalism and dynastic politics, the democratic multiparty political system is weakened and stultified. Ethnicity, the fulcrum on which national politics revolves has, therefore, implied the inexorable death of the political party in Kenya.

This is the unspoken consequence of the double tragedy of the twin tyranny of political tribalism that exists beneath the thin veneer of the preponderant ideological insistence on “order”, a political “order” underpinned by moral anarchy and the assorted vagaries of political tribalism. One, moreover, that suppresses political dissent and one, therefore, that is, at once, anti-people and, thus, anti-democratic, chaotic and violent; and one that perpetuates the endless search for, and accumulation of, power accompanied by skyrocketing corruption. It is, alas, political disorder that is based on a false political stability enforced by the state security apparatus – regular and anti-riot police, intelligence services and the army.

In post-independent Kenya, therefore, the colonial ideology of order is sustained through the very means that were used at the state’s inception – force, authority, bureaucracy and power.