On February 16th 2011, the Arab spring hit the streets of Misrata through sporadic street protests, then spread out into other Libyan cities, ostensibly sparked by the arrest of a human rights activist in the restive eastern city of Benghazi. Libya was simply catching on to the spontaneous civil blowup that was sweeping across the region against a litany of social ills, political mess and economic repression in the wider Middle East.

Libya, the geographical buffer between Egypt in the east and Tunisia in the west fell into that hysterical upheaval along the Mediterranean strip and colonel Muamar Gadhafi just didn’t have the institutional or diplomatic backing needed to stem such a fallout.

It’s often whispered that by not creating independent judicial, parliamentary and social structures but instead building a ‘rule by the people’ Gadhafi had succeeded in building the country around himself. This worked well to foment his grip, but proved to be the fragility of his stranglehold, once the eruption in the Libyan city of Benghazi began to spread outwards. The 3rd century AD city of Benghazi uniquely resented Gadhafi after he took its capital status to Tripoli and stripped it off its stature and prestige during his 1969 coup.

His mistake also partly explains how within just 10 months, the street protests had morphed into an all-out civil war backed by European countries that eventually toppled him, on 20th October 2011, a rare feat, for a leader who’d held to power since 1969. This Arab Spring was simply the culmination of low-grade isolated fights that had impacted the wider Arab civilization since the days of the radical Muslim cleric Sayyid Qutb and his views on the holy jihad in the 1950s.

Starting in his days as a colonel, Qaddafi has always been an ideologically erratic and pragmatic fox who’s Pan-African ambitions unsettled many primitively territorial, and provincially-minded African presidents around him. He misused this ambition though, to advance Libya’s regional clout as the most lucrative player in the Sahelian, sub-Saharan and Arabian political marketplaces.

More than 15 African president and rebel leaders and their respective countries are said to have inordinately benefited from his largesse fueled by his desire to buy or control everyone territorially. It should be remembered that Gadhafi pursued pan-Africanism only after his 1970/80s pan-Arabism dream proved unviable.

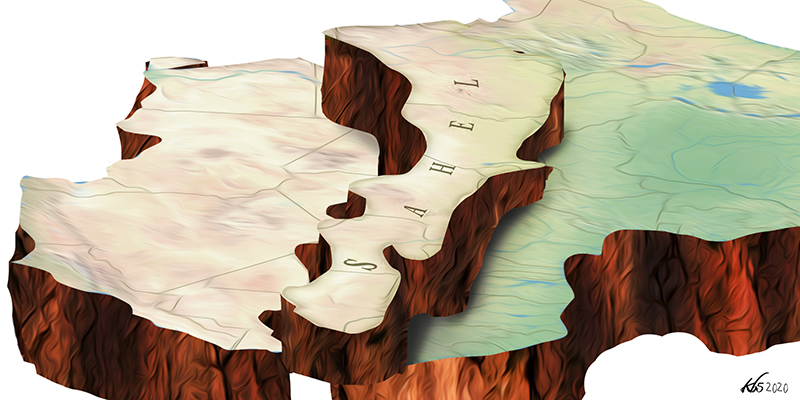

The recent coups in Mali and clashes in Niger and Cameroon are simply part of the wider Sahelian cocktail of devastation caused by converging scourges of climate change, weak regimes, violent jihadis, droughts, rising population, raging poverty, arms smuggling, and corruption. Gadhafi had somehow managed to suppress these regional problems through a combination of threats, cash, promises and charisma.

The war lords, South American drug smugglers through the Conakry coast, and Western mining companies all benefited from Gadhafi’s ambitions which inadvertently stabilized the hostile 9.2 million square kilometer Sahara Desert. The desert measures 4800 kilometers in length and 1931 kilometer width landmass and makes up the largest desert in the world.

So when Gadhafi fell, the Sahelian communities on Libya’s southern borders, and in adjacent borderlands, became the recipients of wave after wave of returnees armed with dwindling cash reserves, ideas about democracy, firearms, superiority complex, and battle hardened combat experience.

More consequentially the Libyan crisis produced an estimated 600,000 returning Tuareg welders, blue-collar employees, miners, specialists, returnee migrants, and worst of all, mercenaries. Gadhafi’s inner circle, African dissidents, his lieutenants, and armed mercenaries ended up with large cash reserves, war experience, huge weaponry caches, and rebel networks running from eastern Senegal to western Sudan and across the Red Sea into the Arabian gulf.

When Gadhafi ruled the Sahel, ordering bombings and peace in equal measure across the region, he’d never had imagined that his end would come in the hands of a 22 year old Omraan Shaban. Shaban, a millennial with an elongated nose, a caricature like moustache, a pouty mouth that mimicked a muffled rage, and sunken white eyes became a sensation as part of the team that shot Gadhafi.

A resident of Misrata in the western Mediterranean coast, Omraan Shaban would become the embodiment of the capture of the strongman in the graffiti-laden culvert in Sirte town, and a symbol of youthful hubris or heroism depending on how you look at it. While the anti-Gadhafi rebellion started in the Eastern city of Beghazi the ultimate rivalry would come down to the two western Libyan cities; pro-Gadhafi Ben Walid town, versus anti-Gadhafi Misrata.

In 2012, 5 months after Gadhafi met his death, Omraan, a Misratan and member of the Shield brigade was part of the retaliation against kidnapping of 4 journalists in the pro-Gadhafi city of Ben Walid when he was captured and tortured for his role in the murder of Gadhafi. He’d later succumb to his bullet wounds in a French military hospital in September 2012 where he was receiving treatment.

Meanwhile further south in the Libyan desert border town of Ghat a tall bearded man, dressed in Bedouin clothes drives atop a white Land cruiser in the desert on the outskirts of the Akakus petroleum plant. Gadhafi’s fall had unraveled a 120 years’ truce that had existed between the city’s majority Tebu and Tuareg tribes close to the Libya-Algerian border.

Aboubaker Akhaty, a Toureg leader in Libya’s southern city of Ubari reckons that for a civilization built atop a gas reservoir, their existence was always going to depend on a skillful negotiation between the oil companies, marauding mercenaries, Tebu herdsmen and the flow of arms from the northern Libyan cities at the Mediterranean coast.

Mercenaries fleeing the fall of Gadhafi entered small cities that lie just across from the Algerian border town such as Ghat, Madam in Niger and Wath in Chad. The contested city of Ubari or Awbari was the last spot in Libya’s southern desert before these thousands of Gadhafi’s mercenaries vanished into the Sahara wilderness some for good, others not for long.

Ubari’s strategic importance in the Sahelian conflict is defined by the geographical fact that it’s flanked by one of Libya’s largest oilfield’s, El sharara to the north and the largest arms and oil smuggling routes to the south of the city and just north of the Chadian border. The Libya’s southern civil war was triggered 3 years after the fall of Gadhafi when Tebu and Tuareg smugglers started disputes over these lucrative smuggling routes.

An estimated 250,000 of the 600,000 workers who left Libya headed home to Niger, while 70,000 crossed into Chad, homeless and penniless and carrying everything with them from guns, household goods, ambition, hopes, ammunitions and versatility.

Southern Libyan towns like Sebha and Kufra, may not mean much to anyone outside its borders, but the fall of Gadhafi marked the beirut-ization of such cities lending them to the whim and impulses of drug lords, arms smugglers, human traffickers and became an existential threat to weak regimes in Niger, Chad, and northern Sudan. These lawless cities served as the rear attack flank for armed rebel groups like the Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and host to rebel leaders, fleeing soldiers, and their Middle eastern, and Eurasian fixers.

With its origins in the scenic Algeria’s Kalbiye mountains which are part of the Mediterranean Atlas ranges, AQIM formerly known as Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat, rebranded in 2007, 4 years before the fall of Gadhafi and would move in to establish its post-Gadhafi territory by recruiting from southern Algeria, south-east Libya and among the Beribiche tribe in the coup-laden northern Mali.

Kidnapped special UN envoy to the Niger’s Agadez region Robert Fowler, a former Canadian diplomat, who was held hostage by AQ-IM for 4 months in the Sahara Desert in 2010, wrote in his book A Season in Hell that “There was a big gulf in the AQIM between those who were black and those who were not. They preached equality, but did not practice it. Sub-Saharan Africans were clearly second class in the eyes of AQIM.” The racially motivated militant groups like AQIM tried filling the vacuum created by the absence of Gadhafi, using recruitment and local spy networks, arms supply, other logistics and illicit trade activities.

By 2013, the post-Gadhafi AQIM spread its tentacles to other parts of the region and forged alliances with murderous groups like Ansar Dine in Mali and northern Nigeria’s Boko Haram. Besides the core Sahelian states, of Mali, CAR, Nigeria, Algeria, Burkina Faso, Mauritania, northern Chad and Sudan’s Darfur region soon became victims of unmitigated tribal, economic and security crisis after the fall of Gadhafi. Returnee migrants, Tuareg mercenaries and the flow of arms from Gadhafi’s looted weapon caches is what created this precarious security situation in Mali and the wider Sahelian states.

Demonstrably, over the last 10 years, the combined effects of these realities have reinforced existing pockets of unrest within the Sahel region, with increased fallouts around northern Mali. The Tuaregs under the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), with their access to lots of arms, anti-tank and explosives continue to drive their desire for a Tuareg republic in the Western Sahara to be named Azawad.

A series of military losses beginning in late 2011 such as the fall of cities like Gao and Kidal to the rebels by the Malian army, had exposed the dire underbelly of a Post-Gadhafi Sahel. Inadequate resourcing, poor tactical leadership, and failure to master the terrain by the region’s national armies led to about 1000 troops either killed, taken captive or deserted in the French-led Operation Serval, Operation Barkhane and Operation Epervier.

The initial push for a Tuareg country was marked by a motivated secular ethno-nationalist patriotism for a people long loathed by their neighboring tribes as well as the French since they massacred an entire French military convoy led by Eugen Bonnier at Goundam in 1894.

While Niger’s Tuareg returnees came to a land for whom civilization had bypassed, their Malian Tuareg brothers pitched camp at Zaka, in northern Mali a scene straight out of the surface of the moon. The strategic difference is that their Malian cousins had armed themselves with guns, even greater ambition, desert Landcruisers, an ideology and guns, lots of guns.

As Gadhafi sneaked around the town of Sirte trying to evade eventual capture and the French drones above in late 2011, Ibrahim Bahanga his longtime ally headed to Kidai region in Northeast Mali, just outside intadjedite, and not far off from his birthplace, at Tin-Essako. His vision-to establish the Tuareg country of Azawad-would outlive him as he fell under a staged accident, in late August 2011, two months before Gadhafi’s assassination.

Bahanga’s death deep in the Malian Sahara Desert in a suspicious car accident few hours before a crucial meeting of Tuareg rebel leaders was the first in a series of major setbacks that were to follow. Few weeks later the Malian Sahel was hit with the worst drought in 27 years taking away attention and crucial war resources-misfortunes were piling. The historically articulate but politically naïve deputy Bilal Cherif took over after Bahanga’s death to continue the quest of MNLA rebel group for an independent Azawad state for Tuaregs.

While Bahanga and Cherif pursued a secular ethno-nationalist ambition, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb AQIM arrived too, with their desert Land cruisers, and awash with guns. There’s was a fundamentalist plan to set up the long desired caliphate that would ideally span the Sahara from Senegal in the West to Sudan in the East and Yemen across the Red Sea. Local Islamic group Ansar Dine awaited the AQIM and together they’d launch a joint war against Malian Army in the north. The 3-way battle lines soon concretized as secular Tuareg nationalists battled with farming bantu southerners in Mali, as well as AQIM’s Islamic militias from the edges of the Sahara.

On January 17th 2012 three months after the death of Bahanga, MNLA launched their first offensive for the liberation of Azawad. The ill-equipped Malian army found itself fighting rebels with competing visions of a liberated desert north; with secular Tuaregs on one front and the Islamic jihadist on the other-causalities mounted. In the south, the Bambara, an ethnic subtribe of the dominant Mande tribe, who made up some of the highest causalities in the Malian military poured out into the streets of Bamako, angered by the images of dead soldiers coming from the Malian insurgency war in the north.

By the time the US state department spokesperson Nuland called the press on 22 March 2012, to voice support for Malian regime under president Amodue Toumani Toure, the military Captain Sanogo had taken over and the president fled the country. As the cool of the afternoon beat off the scorching Malian desert afternoon sun the secular MNLA convoy rode into the Malian city of Gao in pickup trucks, while the Islamic AQIM drove into the town of Timbuktu to the specter of pensive residents. The remaining Malian forward operating bases (FOB) collapsed as Malian Army fled south abandoning stash of cash, weapons, and military infrastructure reminiscent to what had happened to Gadhafi 6 months earlier.

The MNLA Tuareg under Colonel Meshkenani Bela led the conquest into northern Mali and takeover of Gao, but overlooked a critical fact that would haunt them afterwards. They were a minority tribe on the Niger river bend where they were outnumbered by local tribes like the Songhay and the Fulani who were anything but impressed by their takeover. While the Tuareg MNLA entered Gao city through the west, the Islamic Militant Movement for Oneness and Jihad MOJAO which had broken off from AQIM entered through the east and laid claim to sections of Gao-the powdered keg now just needed a fuse.

By March 30th 2012, it soon became clear that Tuareg’s MNLA had neither the capacity nor experience to govern politically and the Islamic MOJAO-buoyed by their merge with terror leader Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s Al Mulathameen-pounced upon the chance to run and stake claim to Gao.

The former Malian army leader turned Tuareg rebel commander Colonel Al Salat Habi, who oversaw the city of Gao on behalf of MNLA had only one option-to negotiate with Al Qaeda, an enemy he’d fought both as an army man in Aguelhoc town and now as a tribal Tuareg commander at Gao.

By April 2012 Northern Mali fell, regional powers panicked, drug smuggling routes tanked and rerouted to Tanzania and Kenya and hostage taking replaced the collapsing drug trade, and raked in upwards of $250 million for groups like MOJAO.

Meanwhile in April 6th 2012 the MNLA under the leadership of Bilal Cherif declared the independence of the state of Azawad. For decades the Malian state had become complacent, even accommodating of the Al Qaeda as a counterforce to the threat of a Tuareg civil war.

Osama Bin Laden’s geographical curiosity of the African Sahel during his time in Sudan, and the desire for a remote desert caliphate had paid off as AQIM ruled the historically and strategically important city of Timbuktu. They imposed a local Muslim Tuareg, Tohar, as their commander. Al Qaida-IM made up in cultural literacy and political tact what they lacked in cash resources.

They partnered with Ansar Dine, used the Tuareg tribesmen in police and civilian roles to smoothen their interaction with local Tuareg populations. But what they achieved through the social and ethnic blend of Ansar Dine, AQIM, through its radical scholars like Abu Al Baraa undid and inspired global rage by introducing public floggings, beheadings, and tearing down of 14th and 15th century historical shrines and structures. The world had to act, and act fast.

It is a testament to the Tuareg’s geo-political illiteracy that their most contested lands is in Northern Mali which is the least mineral endowment of all their lands, smaller in size relative to the adjacent countries and one in which they are demographically outnumbered.

As the situation deteriorated in Northern Mali, the situation is worse in central Mali. There, ethnic Bambara and Dogon tribes organized murderously efficient armed militias, known as Dozo hunters which culminated in Ogossagou massacre that saw 170 Fulani men, women and children murdered.

Across the border in Niger, Bedouin and Tuareg’s Movement for National Justice (MNJ) was already fomenting a rebellion against the massive billion-dollar French uranium mining facility-Areva. It’s a testament to the extreme marginalization that the region remained wretched poor and desolate despite supplying 5% of the world’s high-grade uranium.

In June 2012, Azawad in northern Mali soon fell into the hands of Al Qaeda-IM and Ansar Dine, who didn’t waste time in advancing south to the Malian town of Konna and massacred a Malian army regiment in what came to be known as ‘’The Battle of Konna’’. The world’s patience ran out. France sent its tanks rolling north and east of Mali as NATO jets bombarded their strongholds. The Al Qaeda’s last message while atop grey desert Landcruisers was a promise of retreating into the desert but they’ll soon be back to exert Allah’s vengeance on the infidels.

In the last 8 years since, the Tuareg rebels, local armies, and Islamic radicals have since split into hundreds of highly mobile militias that launch attacks on the border between Mali, Niger, Chad, Algeria, Mauritania, northern Nigeria, and Burkina Faso.

In 2008 Mohammed Yusuf, a 38-year-old Salafi preacher in Maiduguri town, northeast of Nigeria and close to the Lake Chad, fed up by the excesses of the southern Nigerian elites, drew crowds towards the promise of caliphate that will redistribute the oil and mining revenues. Yusuf was an admirer and avowed devotee of 14th century Salafist Muslim cleric Ibn Tammiyah. In mid-2009 his followers Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad famously known as Boko Haram clashed with the Army at a custom checkpoint close to Gamboru area in Maiduguri, Nigeria. He was hunted from his in-law’s house, detained then later on mutilated and his body dumped by the road.

The viral video of his cuffed and badly executed body unleashed a reign of terror and retaliations by his loyalists. His deputy Abubakar Shekau took over and wasted no time in reconnecting with Ansar Dine and Al Qaeda in the Maghreb across the border, and over the next 4 years extended an olive branch to radicals as far as Al Shabaab in Somalia.

In 2013 Boko Haram attacked and killed a Nigerian cop in the Northeast town of Baga followed by a major attack at Bama, and the incensed Nigerian army responded in kind by mowing down dozens, torched houses and left behind estimated 180 corpses and countless who drowned in the nearby lake Chad while trying to flee the carnage.

Lake Chad lies further west of Niger, just north of the Chadian Capital N’djamena and borders Cameron, Nigeria and Niger itself. The 1350sq kilometer lake is the largest water body in the Sahel and one of the last buffers against the ravages of the southward expanding Sahara desert. Between 1978 and 1995 the lake shrank 95% unleashing a humanitarian, ecological, and climatic disaster only comparable to the globally catastrophic drying up of the Aral Sea in the Soviet Union and its direct impact on nearly 100 million lives.

The climatic disaster has been accompanied by civic, geographical and colonial disasters such as the demarcations that cut off the villages from Baga, the regionally largest and closest trading post in Northeast Nigeria. The Chadian regime inadvisably moved the state’s regional offices from the lake’s largest island to the city of Bol on the shores among the Islamic Kanembou tribe and away from the fishing Bougourmi tribe-the two tribes historically don’t get along.

In his heydays Muammar Gadhafi had sponsored numerous plans to topple the CIA-backed former Chadian president Hissène Habré which culminated in the 1986/7 disastrous Toyota Wars in which the two forces fought fiercely atop Toyota Hiluxes supplied by France and the US. The post 1990 Idris Deby’s regime hasn’t done a better job of strengthening institutions and rebuilding the country. He’s committing a mistake that his former northern neighbor Gadhafi had done years earlier and it had costed him his life. Outside of the capital N’Djamena, the only other semblance of civilization is the world’s scenic 18 strips Ounianga lakes in the north and the 3rd largest city of Abeche in the east.

In 1980 Chad ended up in a long running civil war, and Gadhafi in his signature style provided arms, political sanction and logistical support to the Arab Nomads rebels hiding in Eastern Libya. The Sudanese government, well aware of the repercussions of the Chadian civil war pouring across its borders, armed the Arabic-speaking Abbala nomads as a buffer in that long running insurrection. The two groups later merged to form the infamous Janjaweed. Soon enough they drifted away from Gadhafi and provided existential utility to the Khartoum government as they battled with the Christian south.

The Janjaweed in turn lost Gadhafi’s outright support as they increasingly became Khartoum’s weapon of war and supplementary military flank against southern tribes like the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa peoples. Gadhafi didn’t mind though as he had backed Sudanese strongman Sadiq Al Mahdi to assume power in Sudan in 1986 until 1989 when Omar Al Bashir took over.

In mid-August 2011 Sudanese spy chief Mohammed Atta and former president Al Bashir-who was under an international arrest warrant-left for Tripoli and met Gadhafi ostensibly to discuss ‘the means to restore peace in Darfur. 10 months later the same Khartoum would supply anti-Gadhafi rebels in the east with arms and logistical supply rerouted through southwest Egypt.

With Gadhafi gone, the arm stockpiles, battle-hardened desert tribes and latent ethnic rivalries that he had long suppressed have erupted, producing hundreds of small conflicts which were simmering for decades.

My ‘worst mistake’ is what Obama called his toppling of Gadhafi in Libya during his mid-April 2016 interview aired on Fox News. Gadhafi, for all his flaws had outfoxed many adversaries and used his Bedouin credibility and mastery of the desert power politics to navigate complex regional, political, historical and religious interests in the Sahel and just like in Libya he had ensured they were all built around his fist, flair or charisma.

His rule had been marred by the Palestinian cause, the 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing, the 1988 Lorkerbie Plane Crash, the 1989 blowing up of the French UTA airliner over Niger, the 1987 alleged coup plot in Kenya, in a never-ending list of proven and purported mischief. What’s not in doubt is that his 42 years reign had an oversized impact on the local, and regional power equilibriums.

Therefore, his ouster and death in that culvert in Sirte city in October 2011 was inevitably going to create a Sahelian vacuum that set off chain reactions from eastern Senegal through a dozen countries all the way east and south of Sahara. The ensuing chaos was inevitable,. There was just no two ways about it. Former US Defense Secretary in one of his last interviews before leaving office estimated it’ll take about 30 years to quell the militant extremism unleashed post-9/11.

So the current coup in Mali, the rise of AQIM, and AQAP, and forging links with Al Shabaab, Janjaweed, Tuareg insurrection, Ansar Dine, Boko Haram and dozens of embedded militia groups are a legacy to an explosive powder keg for which Gadhafi’s death was simply the perfect fuse.