I first met the distinguished Ugandan scholar Dani Nabudere in 2011, the very year he passed. I had been co-organiser of a conference held in Pretoria, South Africa, to mark the 50th anniversary of the African Union (formerly the Organisation of African Unity — OAU). The conference had been largely organised and funded by Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, the Thabo Mbeki Leadership Institute, University of South Africa, the National Research Foundation of South Africa (NRF) and the Department of Science and Technology, South Africa.

Nabudere was a sprightly 79-year-old, alert, engaged and lively in conversation.

Before the Pretoria meeting, I had actually seen him in action at a conference held in Cairo in 2005 under the auspices of the African Association of Political Science. This was a huge international event with delegates from all over the world and there had been no opportunity to engage with him one-on-one; buying a number of his writings was as close as I got to Nabudere.

Cairo is a metropolis replete with history, culture and countless visual delights. In the permanent whirl of exciting people, cultural riches and hot dry air, not meeting Nabudere then did not seem like such a great loss.

The visit to the art shops that target tourists was an experience in advanced marketing. I bought four scrolls depicting ancient Egyptian heroes, symbols and hieroglyphics. An unusually vibrant woman ensured that I did not leave her shop empty-handed.

The trip to the famed pyramids was nothing short of awe-inspiring. I had gone with an overly cautious delegate from Nigeria who simply did not get the magic of the magnificent edifices, was not willing to explore the mysteries of the inner vaults or take any chances digging deeper below the surface. He saw his holding back as absolute good sense rather than an almost criminal failure of the imagination.

I had tripped and almost suffered a bad fall during our initial explorations at the base of the pyramids and that provided him with the awful excuse not to venture further. What was the point of venturing forth if it could end with a broken leg or worse?

But the Pretoria meeting with Nabudere was very different. It was held at St Georges Hotel in Irene, outside Pretoria, in secluded and serene environs. Also, because it was a slightly smaller event than the Cairo conference, it was possible to really speak with Nabudere as opposed to only seeing him from afar.

During the 2000s, Nabudere had studied and written extensively about the events in the Great Lakes Region (GLR) in the aftermath of Mobutu Sese Seko’s ousting as the paramount ruler of what was then Zaire. Nabudere’s writings on the topic are impassioned, lively and clearly of an activist nature. He was outraged by the rape and plunder of the region by unscrupulous Western speculators and mercenaries out for loot and illicit gain.

But by the end of the decade, Nabudere had found another equally fascinating subject of interest: Afrikology. Afrikology is concerned with the primary retrieval of the lost, submerged and obscured knowledges of ancient Egypt (Kemet), Nubia and Meroe, all of which are great civilisations of ancient Africa.

In Nabudere’s view, contemporary human existence is irreparably fractured, alienating and thus ultimately dissatisfying. Part of the reason for this sorry state of affairs is that ancient Greek scholars who visited ancient Egypt in search of knowledge, culture and civilization misinterpreted and misappropriated what they were given or had been able discover.

The first effect of this gross misappropriation led to the creation of a philosophical pseudo-problem known as the mind/body dichotomy, which is a central motif in contemporary philosophy. Nabudere argues that this motif is both false and misleading. There is nothing, he asserts, that exists as the mind/body problem which has in turn caused societal fragmentation, alienation and false thinking in current human existence. Nabudere then makes his boldest conceptual move, which is to call for a return to ancient Kemetian thought that he believed to be imbued with therapeutic epistemological holism.

But when I spoke with Nabudere during breaks in between conference sessions, he did not dwell on these revolutionary ideas. Instead, he struck me as a seasoned village elder more concerned with indigenous systems of knowledge uncorrupted by Western methods. He freely shared remedies for bites from venomous snakes. We also spoke about the difficulties in pursuing bold independent thought in the current academic environment. And then he indicated that he wanted us to continue our conversations by email.

Nabudere sent me a flurry of unpublished manuscripts. One would eventually be published as Afrikology, Philosophy and Wholeness: An Epistemology in 2011. Afrikology and Transdisciplinarity: A Restorative Epistemology was released the following year. Nabudere argues that “Afrikology seeks to retrace the evolution of knowledge and wisdom from its source to the current epistemologies, and to try and situate them in their historical and cultural contexts, especially with a view to establishing a new science for generating and accessing knowledge for sustainable use.”

I, on my part, began a journey that took me from Nabudere to Cheikh Anta Diop to Molefi Kete Asante and back. There are conceptual links between Afrikology and Afrocentricity. Not only did these philosophies need to be re-discovered, there were entire civilisations waiting to be explored as broken, fragmented selves sought collective healing.

Before he passed, Nabudere founded the Marcus Garvey Pan-African University in Mbale, Uganda. Garvey, as we know, attempted to launch a “back to Africa” movement for the black people of the Americas living under the yoke of racial oppression. Of course, he angered the powers that be and was prosecuted, convicted and eventually deported from the United States back to his native Jamaica on trumped up charges of mail fraud.

Nabudere’s adoption of Garvey’s name for his institution speaks volumes. It demonstrates how serious he was about the project of epistemological decolonisation, an endeavour pursued in other ways by Ngugi wa Thiong’o, another great East African writer and thinker. wa Thiong’o makes language his focal point in order to restore epistemic truth and continuity. In his view, our attachment to European languages is the most obvious manifestation of our state of dependency and most chronically, our psychological unfreedom.

Not only did these philosophies need to be re-discovered, there were entire civilisations waiting to be explored as broken, fragmented selves sought collective healing.

Indeed, the range of Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s project of decolonisation is a result of focused examination of the workings of colonialism and its accompanying effects. He began by questioning the neo-colonial educational arrangement in Kenya as far back as the late sixties when he was still a rather young scholar. In his important book Writers in Politics (1981), he asserts:

Let us not mince words. The truth is that the content of our syllabi, the approach to and presentation of the literature, the persons and the machinery for determining the choice of texts and their interpretation, were all an integral part of imperialism in its classical colonial phase, and they are today an integral part of the same imperialism but now in its neo-colonial phase..

wa Thiong’o goes on to examine the relationship between literature and society and how this linkage in turn radically affects a people’s cultural orientation. A central assertion of his is that “literature was used in the colonization of our people”. To transform this situation, it is then necessary to employ literature for the subversion of imperialism. Throughout Writers in Politics, wa Thiong’o maintains a decidedly Marxist ideological stance and so his analyses of the forces that control the economy, politics, education and culture are based upon the socialist conception of class and society.

In the early stages of his career, wa Thiong’o had reasoned:

For the last four hundred years, Africa has been part and parcel of the growth and development of world capitalism, no matter the degree of penetration of European capitalism in the interior. Europe has thriven, in the words of C.L.R. James, on the devastation of a continent and the brutal exploitation of millions, with great consequences on the economic political, cultural and literary spheres.

Colonialism gave way to neo-colonialism, which wa Thiong’o defines thus:

Neocolonialism . . . means the continued economic exploitation of Africa’s total resources and of Africa’s labour power by international monopoly capitalism through continued creation and encouragement of subservient weak capitalistic structures, captained or overseered by a native ruling class..

In turn, this compromised ruling class makes defence pacts and other unequal agreements with its former colonial overlords in order to secure its grip on political power. The underclass, for its part, is effectively alienated from the structures of power. wa Thiong’o urges that “we must insist on the primacy and centrality of African literature and the literature of African people in the West Indies and America” so as to present a unified front against the cultural and psychological effects of global imperialism. In this regard, the oral literature of our people is of particular importance. Furthermore, he argues that, “where we import literature from outside, it should be relevant to our situation. It should be the literature that treats of historical situations, historical struggles, similar to our own.”

This is a point wa Thiong’o stresses repeatedly in his numerous texts, and one reason that his notion of decolonisation can be recognised to be not only radical but also quite expansive in the way he views the world. Indeed, his understanding of decolonisation has an undoubtedly global dimension, as would be seen later. Furthermore, wa Thiong’o agrees with Fanon that decolonisation is a radical process in which the oppressed and disenfranchised classes all over the world would have to “adopt a scientific materialistic world outlook on nature, human society and human thought”. Hence it is not enough to indulge in “a glorification of an ossified past”. Indeed, he is critical of the somewhat unproductive aspects of traditional societies, as well as of imperialism. As he writes, “The embrace of western imperialism led by America’s finance capitalism is total (economic, political, cultural); and of necessity our struggle against it must be total. Literature and writers cannot be exempted from the battlefield.”

Our attachment to European languages is the most obvious manifestation of our state of dependency and most chronically, our psychological unfreedom.

Since wa Thiong’o’s project of decolonisation is concerned with imperialism on a global scale, he stresses the need for oppressed people all over the world to unite in order to confront it. In other words, if the dynamics of imperialism are global in nature then the counter-power to them should equally be global in its articulation.

However, the task of true psychological and epistemic liberation is first and foremost philosophical. In the recent past in Africa, it was an endeavour that was usurped by charlatans and political opportunists who managed to recast it as a crude politics of nativism or indigeneity as occurred in Mobutu’s Zaire.

If Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s notion of decolonisation incorporates the linguistic perspective, Nabudere’s project, on the other hand, takes in the fundamental philosophical component as an indispensable foundation. It is in essence a call to rebuild self, society, culture and civilisation from the very beginning. It is also a repudiation of contemporary human culture in its entirety as it is incomplete, truncated and therefore profoundly misguided.

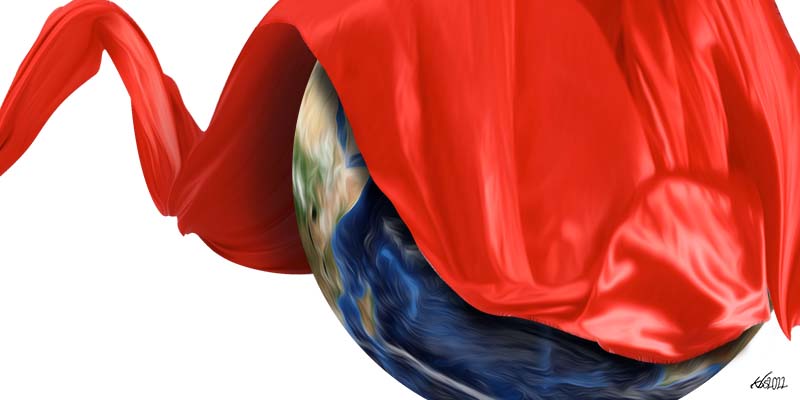

It is also in every sense a call to arms, an annihilation of the false consciousness and civilisation that veil themselves in a cloak of authenticity. In fact, Nabudere proceeds to question our current genetic state of being which might have undergone a fatally inappropriate mutation. And in order to institute a crucial re-alignment, we must reject everything about ourselves, our society and contemporary culture. Nothing could be more radical.

To imagine that such radical ideas had been formulated in the distinguished head of the old, patient and pleasant man I met with in Pretoria a few times. He perhaps did not bother to share them with me then because he knew that he would eventually send me his manuscripts. In this way, he had bridged several disparate worlds: ancient and contemporary, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity, traditional griot and modern-day polymath. Moreover, he had promoted a tradition our modern institutions would find too off-kilter to handle because it had been bold enough to question their existence. And being a custodian of gnostic or esoteric knowledge, when he died, it was akin to a giant baobab falling in a forest. Without a successful passing of the torch, a huge vacuum would definitely be left in the culture, one that has been denied, vilified and suppressed for centuries. First, by external detractors and then subsequently, by the children of the Dark Continent themselves, caught up and invariably obscured, stunted and masticated by the paroxysms of modernity.