Mau Mau has always been a dangerous topic in Kenya. Marked by the brutality of the British counterinsurgency against it, Mau Mau is acknowledged by historians to have been simultaneously a nationalist war of independence, a peasant revolt, a civil war within the Kikuyu ethnic group, and an attempted genocide of the Kikuyu people. This plurality of meanings, which successive generations of citizens, politicians and historians have attempted to smoothen out and fit into neat categories, refuses to be tamed. Instead, the struggle for Mau Mau’s memory continues unabated, with little sign of a ceasefire.

The general contours of the Mau Mau war are widely accepted. On 20 October 1952, the Colonial Office declared a state of emergency in Kenya in response to the growing threat posed by the Mau Mau, a revolutionary military group, who had taken up arms in the forests of the central highlands, demanding “land and freedom”. Primarily involving the Kikuyu, Embu and Meru ethnic groups, but also the Maasai, the Luo and Kenyan Indians, among others, the uprising tore through central Kenya, sweeping up not only the guerrilla fighters hidden in the forests and their British adversaries, but entire communities. Forced to pick between Mau Mau adherence and “loyalist” British allegiances, both of which carried immense personal and ideological risks, rural communities were set ablaze – sometimes literally – as the war ripped families apart and forced people to choose sides in an increasingly complex and violent conflict.

By the most conservative estimations, tens of thousands of people died, mainly Mau Mau fighters and supporters, but also African “loyalists” and a few white settlers. Many hundreds of thousands more were forcibly displaced by the fighting, and by what was termed “the Pipeline”, a systematised network of concentration camps and forced villagisation that set out to quash the movement by “converting” Mau Mau adherents into loyal colonial subjects by any means necessary. By 1957, after the capture and execution of Mau Mau leader Dedan Kimathi, and with the majority of the forest fighters dead or interned, the war was officially over. However, the violence continued.

Shaken by Mau Mau’s surprising military and ideological resilience, and determined to ensure that nothing like this would ever happen again, the colonial government doubled down on the Pipeline system, detaining, and often brutally torturing anyone suspected of harbouring Mau Mau sympathies. In the ensuing decade, it became clear that the rebellion had been quashed. But the writing was on the wall, underlined by the scandalous revelations of the colonial government’s conduct, Kenya’s independence was inevitable and urgent.

As one struggle was ending, however, another was just beginning. Now, the race was on for ownership of Mau Mau’s history. For the British, that meant Operation Legacy, a systematic destruction and removal of all evidence of their criminal conduct during the war. For the incumbent post-independence government, it meant carefully curating a Mau Mau narrative marked more by silences and omissions than by commemoration of the events of the war.

By the most conservative estimations, tens of thousands of people died, mainly Mau Mau fighters and supporters, but also African “loyalists” and a few white settlers.

For the hundreds of thousands of citizens who were survivors of the war, it meant finding ways outside of the public history-making to process the trauma and preserve the memories of the war. While the British government has been rightly condemned for its attempts to cover up the atrocities they committed and commissioned during the war, far less has been said of the Kenyan government’s complicity in the public silences around Mau Mau. For Jomo Kenyatta and his government, the past was a politically dangerous topic that needed to be carefully managed. Mau Mau, he proclaimed, was not to be discussed, and the organisation remained a banned terrorist group. The last holdouts in the forests were rounded up and persuaded to surrender, or arrested, and those who spoke about the movement publicly outside of officially sanctioned narratives often ended up in prison, in exile, or in the morgue.

Mzee Kenyatta’s mandate was clear: Mau Mau was to be forgotten, and not to be discussed publicly. The organisation remained an illegal terrorist group throughout the Kenyatta and Moi eras, and was only legalised after Mwai Kibaki’s inauguration in 2004. The “forgive and forget” policy of Kenyatta and his successor had several interlinked purposes. A generous assessment is that Kenyatta wished to promote national unity and to focus on a shared future rather than a divided past. However, this is only part of the truth. Personal interests needed to be protected, especially those of former loyalists who now held top government positions. In addition, land justice and redistribution, the key demand of the Mau Mau, and later the Kenya Land and Freedom Army – which emerged after the war, and named among its members many Mau Mau hold-outs – would not be a cornerstone of the post-independence political policy. In fact, many veterans returned from forests and camps to find that what little land they did have had been taken from them, and that the only recourse for them to regain it or acquire new land would be to buy it from the government.

Since Mau Mau had been a full-time commitment, and concentration camps did not award salaries, while loyalist Home Guards were paid, an inequity emerged between those who were able to afford land and those who weren’t, which fell along lines of allegiances during the war. A final reason for Kenyatta’s desire to silence any public discussion of Mau Mau was that British interests still needed to be protected. If Kenya wanted to emerge from the 1960s as part of the global economy, it would have to dance to the tune of its former colonisers, which meant not embarrassing them with tales of their past atrocities. All in all, it would be better to forget the whole sorry affair.

Personal interests needed to be protected, especially those of former loyalists who now held top government positions.

In practice, this meant a careful selection of which fragments of the truth of Kenya’s Mau Mau past could be discussed and by whom. As a student of Kenya’s national curriculum, if you learned anything at all about the history of decolonisation, it adhered to a specific narrative: colonialism came to an end when Jomo Kenyatta and other brave constitutional nationalists came to an agreement with the British. Depending on your age, you may also have learned the names of some long-dead Mau Mau heroes and heroines who helped win Kenya’s freedom.

Certainly, there would not have been any discussion of the ideological roots of the Mau Mau movement, rooted in land justice and economic freedom or a critique of the betrayed promises and the land-grabbing by the post-independence political elite. The issue is not that these things are untrue – although from a historical perspective, some of them are inaccurate – but that they are presented as complete truths. While it is true, for example, that Jomo Kenyatta was tried and imprisoned along with five other nationalist activists at Kapenguria for being a Mau Mau ringleader, historians now agree that Kenyatta’s conviction was based on trumped up charges that did not align with Kenyatta’s ambivalent relationship to the militant guerrilla movement.

Kenyatta was an African nationalist, but he was not a Mau Mau leader. Outside of the national curriculum, selective amnesia could most clearly be observed on national holidays, particularly Independence Day and Kenyatta Day. On such occasions, speeches glossed over the painful past, and focused on the economic development of the future. President Kenyatta and his successor Daniel Arap Moi seldom spoke explicitly about the history of the Mau Mau movement, instead alluding to the vague need to “commemorate Mzee Kenyatta and the blood that was spilled in our struggle for independence”. The careful ambiguity about whose blood that was, and why it might need to be commemorated speaks to the fact that Kenya’s Mau Mau past remained politically dangerous. Veterans could be used to mobilise voters in specific regions of the country, but would otherwise remain nameless, and, more importantly, silent.

My research as a historian has focused on what happened to the memories of Mau Mau in the face of this public silencing, and seeks to understand what grassroots memorialisation looks like in the face of political amnesia. Working with oral histories from veterans and their families, alongside archival material, I have been consistently struck by the plurality of experience that characterises the Mau Mau war. There is no one definitive historical truth, and a key part of the mishandling of Mau Mau histories in the decades since independence has been rooted in the ill-fated attempts to discipline the complicated and fragmentary history into something that might fit neatly into tales of heroes and villains.

Through my research, I have found that a rich material culture of Mau Mau has existed in rural communities since the end of the war, one that was astutely aware of the history-making endeavours, but did not adhere to them. While the archival material on Mau Mau was systematically destroyed at the national level, it was carefully preserved by thousands of individuals across Kenya, for whom forgetting the war was never an option. Veterans pulled out boxes of photographs and documents, personal archives carefully preserved far from the censorial eyes of public history-making. Many pulled up their sleeves or skirts to reveal scars, offering their very bodies up as living monuments to the war. Away from the ceremonial lip service of national holidays and hero-worship of the official narratives, these veterans found ways of memorialising Mau Mau on their own terms.

If Kenya wanted to emerge from the 1960s as part of the global economy, it would have to dance to the tune of its former colonisers.

For many years, Mau Mau history was marked more by what is not said in public than by what is said. It has, for successive generations of Kenyans, been characterised by profound silences: family members who never came home, land that was lost, unmarked graves, and gaps in family trees. However, this should not be confused with forgetting. In fact, the silences around Mau Mau and who was permitted to speak of it have often served to amplify the unhealed traumas of the past, which sit just below the surface of everyday life.

In 2003, President Kibaki’s un-banning of Mau Mau allowed veterans to organise publicly for the first time, and saw the beginning of attempts to memorialise the conflict and to portray Mau Mau fighters in a positive light, as heroes of independence. However, there is still no national museum dedicated to histories of the struggle, and national institutions remain reluctant to address the complexity and unhealed traumas of Kenya’s Mau Mau past. This period in the early 2000s coincided with the emergence of a new generation of urban youth, enlivened by stories of the ferocious fighters and their brave struggle for land and freedom, who created their own myths and memorial cultures of Mau Mau.

In Nairobi today, Mau Mau sightings are a frequent occurrence. Yes, there are a few national monuments, and a small display at the National Museum of Kenya, but, more importantly, Mau Mau appears in more quotidian forms. Dedan Kimathi sits astride a matatu, weaving through traffic, sandwiched between Tupac Shakur and Bob Marley. The words “Mau Mau” are spray-painted on walls and on the mud flaps of trucks. Young men wear dreadlocked hair and t-shirts with Kimathi’s face.

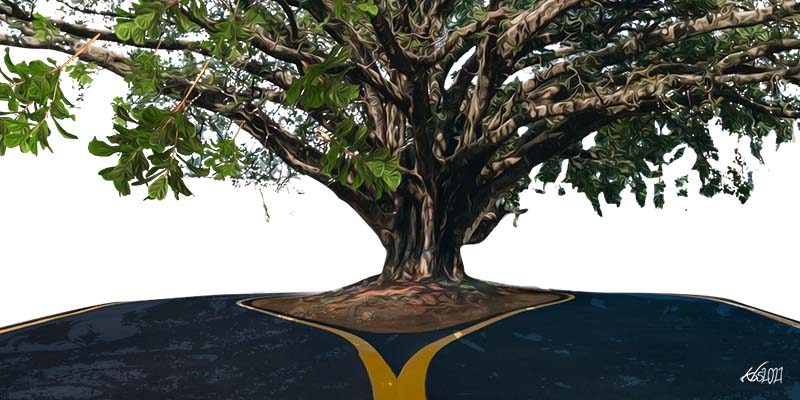

These representations of Mau Mau history have a lot to say about how memories of the war have come to take on new meanings for Kenyan futures. Mau Mau in general, and Kimathi in particular, have entered into an iconography of revolutionary history that holds a strong sense of continuity for young urban Kenyans today. After all, the grievances of this generation are disturbingly similar to those of the generation of the 1940s who took up arms in the Mau Mau movement. For both, it is about land and freedom. The slum demolitions and police brutality that animates young people in Nairobi and Mombasa and Kisumu have their roots in a not-so-distant colonial and post-colonial past. Increasingly expensive and precarious living situations, lack of economic opportunities, and a government more interested in accruing wealth and resources for a small elite than in ensuring the welfare of all citizens led to the Mau Mau war, and this struggle continues.

In this sense, contemporary popular representations of Mau Mau speak to the fact that Mau Mau cannot be neatly placed in the box marked “distant past” only to be opened under governmental supervision on Mashujaa Day, when veterans are wheeled out to recite carefully crafted histories of heroes and heroines. Mau Mau is still a living present. Despite their best attempts to bury the bodies, they lie in very shallow graves.

The lack of public history has led to a grassroots memorial practice that is as imaginative as it is true. The material cultures they have created around Mau Mau speak to an active attempt to reclaim histories of the struggle. What archival material has been revealed and declassified in the UK and in Kenya is coloured by the colonial gaze, so that there are still questions of authorship that remain to be answered by national historical institutions. What does addressing these archival inequities mean? Ignored by institutionalised history-making and, at times, actively silenced, new generations have continued the veterans’ practice of personal histories, crafting their own living monuments to the war. The model of a museum is unsuited to such histories, which are marked by their strong emotional truth more than their historical accuracy, and which need to live defiantly within communities, not cloistered behind the guarded gates of national museums.

The careful ambiguity about whose blood that was, and why it might need to be commemorated speaks to the fact that Kenya’s Mau Mau past remained politically dangerous.

This rejection of the conventions of public history, often characterised by material cultures produced by the elite, has liberated Kenyans to imagine their pasts, and, in turn, their futures. Following in the tradition of writers and artists of the 1970s and 80s, who often paid dearly for their representations, Kenyans use fashion and hip hop and graffiti to write into the decimated historical archive, harnessing their imaginative power to unravel the silences and reawaken a revolutionary sentiment.

National history projects like clear lines and straight narratives of heroes and heroines, but Mau Mau cannot and will not fit into such simple constraints. Mau Mau historical plurality reminds us that there is an urgent need to redress the injustices of the past, not by presenting a simple counter-narrative to the official sanctioned myths surrounding the war, but through embracing the plurality of experiences around Mau Mau pasts, presents and futures. These histories were never forgotten. They were deliberately obscured, but have lived active lives throughout the years of political forgetting. They are infused into our national consciousness, into our knowledge of who we are and were and might be.