If we spoke a different language, we would perceive a somewhat different world.

– Ludwig Wittgenstein

Matters of form, usually viewed as ornament, are commonly in fact matters of argument.

– Deirdre N. McCloskey

This short article explores the construction of Economic Neologisms in English and their global impact on shaping implicit and explicit policies in countries around the world. I focus on how economic neologisms in the English language project an air of neutrality but in fact have no basis in the socio-economic realities of developing countries. This is demonstrated through explaining the role of English as an organised system of thought, the nature of academic English in economics and its influence on developing countries, a recent example of the use of Value of Statistical Life (VSL) in Pakistan based on a misguided comparison with the US, and the limitations of interpreting other languages in English.

English as an organised system of thought

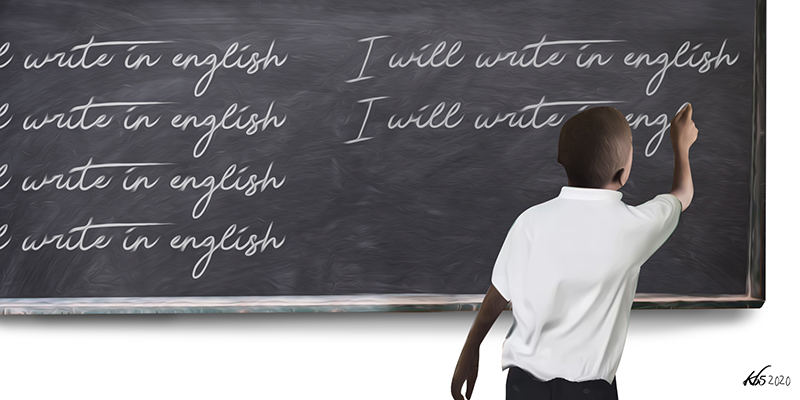

One of the great successes of empire, binding its economic and cultural usurpation of the colonies, was the proliferation of English as a global language and as the only “official” language of the world. The strength of this legacy has defied time; the diverse geographies, languages and cultures of India are more strongly overcome by the use of English today than by any local language, signifying how English, as the language of the colonial state, took precedence over the many languages of India.

Although the Francophone sphere has remained a well-preserved niche, this enclave is no match for the global stamp of English. Outside the colonies, English has very much overshadowed the regionalism of the European Union (EU). International organisations such as the UN, the IMF and the World Bank continue to lean towards the ascendency of English, in spite of their charters of multiple languages. The rise of the Chinese language as a formidable opponent is uncertain.

As the most dominant currency, English is not particular to race, but cuts across class and geography. Its exclusiveness is not so much in the basics of the spoken word but in the intricacies of how it fuels knowledge. People across countries can communicate on some basic level using minimal English, but the source of its inaccessibility lies in the dense articulation of the language as a specialised realm of knowledge production. This is not straightforward, since many academics from developed countries do not use English as a first language; on the other hand, many in developing countries have learned it from their earliest years of education. Nonetheless, a distinction emerges in the use of English, not simply as a language of communication but as an organised system of thought. The empire’s proliferation of language reproduced a structure of socialisation, which streamlined a linear set of ideas as opposed to embracing diverse and alternative systems of thought.

The Russian linguist V.N Voloshinov, explored the origins of language as an inherently social phenomenon, and saw language as the most efficient medium of capturing the dynamics of material changes. He described the “word” as “the most sensitive index of social changes.” Importantly, for Voloshinov, the significance of words was not just limited to their representational role of capturing change but went beyond the symbolism, enabling a transformation, which added new dimensions and layers to a word’s original meaning.

‘‘[l]ooked at from the angle of our concerns, the essence of this problem comes down to how actual existence . . . determines the sign and how the sign reflects and refracts existence in its process of generation”

Voloshinov aimed to develop a theory of linkages between structure and agency in the framework of particular semantic frameworks. His emphasis here is on how signs are influenced; refracting the material and social existence of a phenomenon. The socialised impact of English, as an imperial language lies not simply in what it signifies but also in what forms its refractions take on. Patois and Pidgin English are some particular linguistic examples. Additionally, English has also been instrumental in exporting Anglo-American soft power to developing countries. This is visible especially in the formation and the role of media in developing countries. These derivative languages and effectively hollowed cultural influences are accompanied by the shaping of the global academic landscape, with English as the monopolistic medium for exploring knowledge. The consumption of the English language precedes consumption in any sphere of knowledge. In economics, the refractive role of English lies in how it shapes ideas and economic policies.

The medium is the message

As a conduit of pedagogy, the English language has a history of not simply conveying the message but actively creating it. Concepts like “western enlightenment”, “scientific rationality” of the market and a consequent linear vision of growth, encompass a message of neutrality because the language embeds an exclusivity, canonising a singular system of thought. This canonisation is fuelled by ideologies, which seek homogenisation across geographies; the “Washington Consensus”, for instance, was exported beyond Washington but never as a consensus. In addition, compared to other social sciences, economic concepts and neologisms carry the potential of shaping the entire direction of scholarship. A brief look at any basic course in the history of economic thought verifies this.

The ascendency of neoclassical economics and its impact in transforming the entire discipline to become an imitation of natural sciences had a reductive impact on the scope of economics as a social science. For Philip Mirowski, the pursuit of projecting economics as a “science”, borrowing metaphors from physics and resorting to mathematical formalism, is rooted in the Western tradition of economics. By imitating natural sciences and giving a central value to empiricism, neoclassical economics transforms how metaphors operate. This is evident in metaphors, which constitute the conceptual basis and pedagogy of economics using natural laws but ultimately bearing little resemblance to the social processes, which constitute an economy. Statistical rigour and mathematical proofs thus often take a life of their own by validating a seemingly value-free concept.

As a conduit of pedagogy, the English language has a history of not simply conveying the message but actively creating it.

If economics is considered as a repository of selectivity as well as of careful omissions, the responsibility of exploring the structure of metanarrative behind the curated message is a constant struggle for those outside this thought system. Other languages are inserted in the English language as loan words, strictly tied to culture (such as the Chinese concept of Guanxi or the Japanese business philosophy Kaizen). Words also sneak into English through a shared history of colonial/imperial experiences. However, “foreign languages” have no power to determine economic methods or produce similar neologisms. Economic concepts in English on the other hand are canonised, refracted and socialised as the most objective and rational ways of determining other concepts such as efficiency, growth and ultimately, ways of living life. The usage of the Value of Statistical Life (VSL) in context to the COVID-19 pandemic and its internationalisation as a “global policy” tool is of relevance here.

Interrogating the universality of economic neologisms: the value of statistical life (VSL)

The Value of a Statistical Life (VSL) is normally used to monetise fatality risks in cost-benefit analyses and reflects the amount of money that a society is willing to pay for the reduction in the probability of the loss of a human life. This human life is generally, a statistical, hypothetical person on a population-average basis and refers to the hypothetical victim of a circumstance or of a policy or the lack thereof, and fully discounts class, ethnicity, nationality, religion or other characteristics that such a person may or may not have. It is designed as an objective, value-neutral concept to be applicable in contexts, where cost-benefit analysis would enable a synthesis or reach an objective resolution, to an empirical evaluation of saving lives.

As a statistical measure of predicting fatality risks, VSL, like Ogden tables, etc., is a construct and subject to the broader operations of how an economy is structured. This method of assessing risks to human lives is ultimately a valuation exercise and the underlying ethical concerns are tied to how capitalist systems perceive value and public utility. This is important since the construction and adoption of VSL in the US has a complex history, rooted in its origins in the Cold War.

These considerations remain unexplored, especially in the internationalisation of the concept. For example, VSL for climate change, calibrated to different contexts of developing countries, is in widespread use. These calculations do not address the fact that climate change in developing countries has been primarily led by accumulative patterns initialised and deepened by developed countries, rooted in the history of colonialism. For those arguing for a long-standing case of climate reparations, such applications of VSL to developing countries would be akin to technical fixes that pay no attention to history. Tailoring the VSL to country-contexts also raises questions about the criteria of implementing VSL based on mitigating fatality risk. Although VSL has its origins in the Cold War, it has not emerged as a basis for measuring the fatality risks of soldiers or casualties in recent conflicts, for instance in the “War on Terror” in Afghanistan and the invasion in Iraq. Needless to say, in situations which are invariably related to the opportunity cost to human life, VSL is an objectionable measure.

“Foreign languages” have no power to determine economic methods or produce similar neologisms.

However, the current Covid-19 pandemic has revived the appeal of using economic modelling based on VSL. In a recent paper, Zachary Barnett-Howell and Ahmed Mushfiq Mobarak used VSL to advocate social distancing policies in some “developed” countries as opposed to others, in the developing world. Pakistan was one of those countries cited in the paper. The Government of Pakistan eased its lockdown on 9 May 2020, with the Planning Minister invoking this paper among other reasons to support the government’s policy stance. As a result of the ease of the lockdown, the infection count in Pakistan increased from 36,000 (April-May 2020) to 165,062 (June 2020). A full account of the paper, its critique and the situation in Pakistan has already been covered succinctly by Khurram Hussain and also debated by academics and activists here (in Urdu language). Without repeating the details of their critique, I summarise the bases for the largely erroneous use of VSL in this case, as follows.

Barnet-Howell and Mobarak’s estimated country-specific costs of mortality and use of VSL is based on another paper by W. Kip Viscusi and Clayton Masterman. The latter employed an analysis of data from the US Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) to value VSL, “to avoid hypothetical bias”. Referring to low to upper-middle income countries as “economies” as opposed to upper income “countries” Viscusi and Masterman conclude from a base US VSL of US$9.6 million, that different countries value human life differently. Following this paper, Barnet-Howell and Mobarak used this US VSL of US$9.6 million, to then discuss essentially Covid-19 policy recommendations, employing the VSL figures suggested for different developing countries.

A first problem with this analysis is that this value does not in any way reflect the value that the US society places on a human life vis-à-vis the Covid-19 pandemic. Instead, it is actually a representation of hypothetical costs to US policy makers and businesses, of making marginal improvements and mitigations to all those risks, be they in the workplace or by the quality of civic infrastructure and so on, which affect human life. Aside from issues of monopoly pricing across the wider economy, the US has the most artificially inflated healthcare costs in the world. It would follow that VSL (if indeed a normal good as Barnett-Howell & Mobarak seem to be insinuating) would thus be equally over-valuated.

For those arguing for a long-standing case of climate reparations, such applications of VSL to developing countries would be akin to technical fixes that pay no attention to history.

This situation is not true of other countries including emerging economies, in which different systems of goods and services pricings persist. Using this highly (and artificially) overvaluated US base VSL as a concrete foundation for “upper income countries” as the basis for an extrapolated comparison is thus unjustified. Alongside having amongst the highest global rates of infection and deaths, the United States also has one of the highest unemployment rates, and attendant social unrest, as a result of the pandemic. If anything, the Covid-19 pandemic shows that life in the US has become exceedingly cheap, and indeed far cheaper than one would have imagined merely a decade ago. The application of VSL in this manner assumes that monopoly pricing in the US is somehow a base condition by which to measure the rest of the world. Such attempts at valuation only serve to insinuate a global marketplace for human lives, almost imperialistically conforming to the norms of the American market and economy.

Interpreting methods

Methodological problems are often also problems of unchallenged ideas. Economic ideas, concepts and textbooks in English are translated and absorbed globally, in effect strengthening the canon as opposed to opening the space for careful examination. Translations are not interpretations. Describing the third world literature’s feeble attempts at expanding text in other languages, Aijaz Ahmad reminds us that a “mere aggregation of texts and individuals does not give rise to the construction of a counter-cannon . . . for the latter to arise there has to be the cement of a powerful ideology.”

Attempts at counter-ideology are made more complex by the fact that knowledge production in English reproduces the erasure of knowledge production in other languages; many academics writing in English in fact lose formal writing and speaking skills in their native languages.

For these reasons, decolonising knowledge in economics is a complex process since it entails excavating alternatives, which demands a reimagination of possibilities and limits. Being truly multilingual would mean equal attention to all languages. Separating the objectivity of the language from its message and pluralising and empowering pedagogical practices in other languages is a start.

–