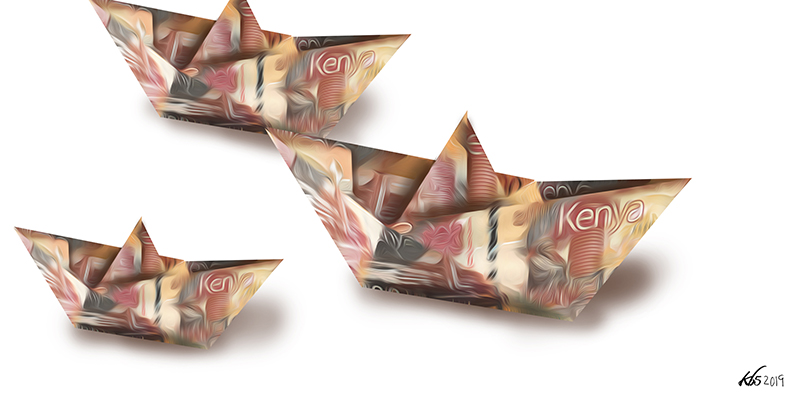

The Korean economic landscape is dominated by chaebols, Americans have conglomerates, the Japanese have Zaibatsus, Germans have Mittlestands, while Kenyans have, well, let’s call them Mamols – a cluster of faceless, powerful, family-owned enterprises whose stake in the economy is massive and diverse and which form the core to the competitiveness of the Kenyan economy. Mamols, the word derived from native Dholuo for tendril-like tentacle plants that intertwine their way into multiple nearby vegetation to form a strong mesh-like interconnected undergrowth.

Kenya’s economy, as currently constituted, represents a feudal-like family economy dominated by a few well-capitalised family-owned units at both the top and mid-tier. At a glance, the majority of the 7.4 million small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) in Kenya are conventionally family businesses owing to their initial source of capital, ownership and day-to-day operations.

A chaebol, or in our case a mamol, is a large industrial firm that is run and controlled by a founder and his or her family. Their internal make-up is that of a large number of diversified affiliate brands, products and markets under a patriarch whose power over the business operations often exceeds legal authority.

There are significant differences between Japanese aaibatsus, Korean chaebols, Kenyan mamols, and American conglomerates, key among them being the source of capital. The aaibatsus organised around a bank, chaebols were prohibited from owning a bank, their American counterparts go to Wall Street, while Kenyan mamols rely on internal revenues and private equity for growth.

The constitutive nature of these businesses is any profit-making venture patronised by two or more family members in its workforce and the majority of ownership or control lying within that family. Traditionally, such corporate structures place the founding patriarchs and matriarchs at the helm and family members in ownership positions, allowing them to exert direct control across the board. Family-level investments are known to tap into the general social immobility of capital, which tentatively guarantees that if properly transitioned, the resources can stay within the family for anywhere between five and six generations.

Family-owned businesses are the backbone of the global economy. The Conway Centre for Family Business estimates that 35 per cent of Fortune 500 companies are family-controlled across the full spectrum of firms, from small niche outlets to major brands. In fact, family businesses account for 50 per cent of the U.S. gross domestic product, generate 60 per cent of the country’s employment, and account for 78 per cent of all new job creation.

The East Africa region has a wide array of such firms, which shrewd private-equity investors can explore in the medium to large segment with market caps of between $10 million and $100 million. The research firm Asoko’s data identified over 10,000 firms in this revenue bracket across a diverse range of markets in East and West Africa.

The Conway Centre for Family Business estimates that 35 per cent of Fortune 500 companies are family-controlled across the full spectrum of firms, from small niche outlets to major brands.

Unsurprisingly, only a handful of the thousands of family-owned firms in Kenya reach elite status or provide strong products, brands, and services across the region, thus significantly influencing the export basket. Extrapolation of local studies indicates that there are 645 family-owned firms earning between $10 million and $100 million annually in East Africa, with nearly three out of every four of these companies being Kenyan, followed by Ethiopia, at 17 per cent, Zambia, at 5 per cent, and Uganda, Rwanda and Tanzania, at 2 per cent each. Asoko’s research further identified 490 family-owned Kenyan firms earning annual revenues in excess of Sh1 billion across a wide range of industries; of the 490, 14.3 per cent, or 70 companies, earn more than Sh5 billion, 22 of which earn over Kshs 10 billion every year.

Within these hallowed halls of prime family-owned enterprises that churn premium products, there exist complexities and contradictions cutting across the family-business divide in which virtues and vices on one end diffuse to the other end with speed and ferocity. Much more intuitively, their very nature as family-owned businesses results in unique models of starting, running and decision-making, the end result of which is usually a surprising litany of dilemmas: political interference, their worries about work and sibling rivalry, inheritance squabbles, and most of all, the fears for the heirs.

Locally, the roughly 500 sprawling family-run conglomerates with at least $10 million in revenues are the understated cornerstones of Kenya’s economic, political and social landscape. Taken together, they make up the silent pillars of the nation’s versatile economy and include the likes of KenPoly, and ICEA Lion, with Ramco being among the oldest of them all. Unlike the globally renowned family-owned firms like Walton, the Korean Chaebols or Japanese corporate giants, most African Kenyan Mamols in particular, prefer to court as little publicity as possible partly because corporate culture generally abhors uncourted publicity given the landmines of publicity.

The PwC 2018 Family Business Survey indicated expected revenue growth in 82 per cent of the family-owned enterprises – a major feat in this era of fiscal constraints and declining exports in the country occasioned by high energy costs and over-taxation. The top obstacles to surmount are corruption (72 per cent), accessing the right skills and talents (52 per cent), prices of inputs (52 per cent), competition from cheap imports (52 per rcent) and the pressure to innovate (50 per cent).

Locally, the roughly 500 sprawling family-run conglomerates with at least $10 million in revenues are the understated cornerstones of Kenya’s economic, political and social landscape. Taken together, they make up the silent pillars of the nation’s versatile economy…

These massive firm’s opaque and often unexamined governance and ownership structures and oversized influence, coupled with their cosy relationship with regulators, often lends credence to fears of influence-peddling. No doubt, as the fiscal condition of the political economy under the Jubilee government tightens, it will cast an intense spotlight on these firms, just at the time when many are navigating murky generational transitions. Absent are clear models of generational transition of wealth acquired and sustained through the patriarch’s political or social patronage, which leaves the heirs ill-prepared for their inherited fortune.

Given the nature of our political economy, most of these firms rely on close cooperation with the political structures for their operations, inducing decades of political goodwill, and support. The guarantee could be in the form of subsidies, loans, and tax incentives only imagined by their rivals. That the president, cabinet secretaries, and top bureaucrats can trace their political fortune to the attendant patronage of family capitalism gives the best glimpse of these firms’ impact in our political infrastructure.

In Latin America, family capitalism is at its most efficient in the pursuit of political power and using tentacled connections to launder public and private resources. In Argentina, the family-owned firm’s goal is political conquest with presidential and gubernatorial positions as the ultimate prize.

In keeping with the largely conservative investment decisions of these investors, 60 per cent of them populate the agricultural, industrial and manufacturing sectors of the economy. A survey by consultancy firm Knight Frank shows that these clusters have allocated 25 per cent of their investment portfolios to equities, 22 per cent to property and 22 per cent to cash or cash equivalents, with only 3 per cent in private equity and another 3 per cent in luxuries stuff such as art, wine and luxury cars.

Given the nature of our political economy, most of these firms rely on close cooperation with the political structures for their operations, inducing decades of political goodwill, and support. The guarantee could be in the form of subsidies, loans, and tax incentives only imagined by their rivals.

Curiously, Kenya’s leading family-owned enterprises are still within the first three generations of ownership, a fact tied to the barely 60 year-old independence in this 100 year-old plantation. Large industrial firms like Ramco, which traces its roots back to precolonial 1940s, signals a growing sustenance and entrenchment of these Mamols into the heart of the nation’s political economy. Ranci is currently chaired by one of the sons of the original patriarch who is subordinated by members of the third generation, a feat replicated by only one other company, which is on its third generation of leadership from within the family.

Lots of other mamols are still being ruled by first- and second-generation leadership and often silently face precarious generational transitions. Surprisingly, about 17 per cent of the top family-owned conglomerates have a succession plan ahead of the global 14 per cent average. The generational divide, coupled with increasing complexity and diversity of skills that the firm needs as it grows, predisposes the second or third generations who take over the reins of family businesses to be more open to outside investors, and hiring of experts. Globally, just 30 per cent of family businesses make it through the second generation, with only 13 per cent passing three generations, which is the context within which lots of these huge Kenyan firms exist.

What’s their story?

As the founders phase out, there’s the compelling case of having fantastically wealthy heirs dealing with wealth that is inherited rather than earned, which may predispose them to hubris. The perpetuation of the firm is not a great deal more fulfilling to them as it was to the founders. Despite being vibrant contributors to the economy, family-owned businesses face corporate governance issues, political wheeler-dealing and flaky succession plans whose overall impact limits the company’s lifespan. In total, just over half of Kenya’s family businesses reported having a succession plan in place, with two-thirds indicating that the next generation was already part of the business.

The litany of generational differences, fraying and differing visions of the future and emerging challenges and gaps compel the patriarchs to invoke external talents to increase the talent pool available for operations. Consequently, a more recent survey has revealed that family businesses in Kenya are in robust health, with revenues expected to continue growing in four out of every five firms.

According to the Finnish Family Firm Association 2009 report there are three prime ownership models in these family-owned firms: first, the owner, active in governance with three overlapping roles as manager, family member, and owner; second, the owner, non-active in governance, is a family member and owner; and third, non-owning, active in governance family member has two roles as owner and as manager. A non-family member active in governance can be a member of the board or management; also a non-family member can be owner as a capital investor or as a managing director who owns shares of the family firm.

Then there are the family members, who have no role as owners or managers and who are typically spouses (in-laws), trustees and next of kin. Relatives of most of Kenya’s stock market billionaires prefer to stay out of the public limelight, avoiding governance roles, such as directorships, in the portfolio companies where their families control major shareholding.

The Family Business Survey 2018 shows that the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE)’s main value proposition to mamols – visibility, access to financing and a divestment platform – appeal to the 46 polled companies whose turnovers range from Sh500 million to more than Sh10 billion. Eighty-five per cent of the Mamols rely on internal cash and 83 per cent on bank lending/credit lines, while 59 per cent prefer private equity at a higher percentage than the global average of 39 per cent.

What complicates analysis of these behemoths is that Kenya is known to have a large group of politically-connected superrich families who have hidden their wealth in trusts and a labyrinth of companies to evade taxes. In 2015, a list of 191 individuals and 25 offshore companies linked to Kenya was leaked from the Mossack Fonseca legal firm and published in what came to be known as the Panama papers. The companies and individuals held the cash equivalent of over Sh15 trillion laundered and transferred from Kenya.

The dark side of family businesses

During the United Nations International Day of the Family in Nairobi, Justice Aggrey Muchelule said that the Family Division has resorted to alternative dispute resolution mechanisms in the quest to resolve the over 13, 000 succession cases over family-owned assets left behind by parents, spouses or other benefactors. Court and political battles over large firms and other properties left to heirs of prime family-owned firms in Kenya pop up regularly even where there is a will. Few of these cases arrive at amicable solutions.

The properties in dispute range from shares to money stashed in banks and tax havens abroad and businesses and other assets, but land still remains the most contested asset; some of these cases have been unresolved since the 1980s. Mbiyu Koinange, James Kanyotu, Gershom Kirima, Jenga Karume, and JM Kariuki’s families are among the affected as the Unclaimed Financial Assets Authority (UFAA) has had to seize their dividends and shares following family feuds over ownership and succession.

Despite their tenacity, the family business model often tends to undermine its own longevity, profitability and efficiency through political favouritism, succession by unfit heirs, endless feuds, and sleaze, including excessive and unnecessary luxury spending on the company’s tab. Examples of drastic declines in family fortunes can be found in Russia and the Middle East.

Locally, while addressing the family of the late Murang’a-born oil tycoon Thayu Kabugi during his burial, President Uhuru Kenyatta, whose family has a major controlling stake in the Kenyan economy, reflected that assembling an estate worth billions of shillings was not a simple task as it takes a lot of struggle, toil and back-breaking work. “But we are seeing a situation whereby families of these icons of our economy go after each other’s throats days after the demise of their economic fortune heroes. That is not the way to go and I would urge all families to desist from such tussles,” he said.

The looming political and economic crises simultaneously plaguing the country has exhausted the country’s political-economy’s capacity to self-correct. A major hit to the economy, the population bulge, massive corruption, and the upcoming elections and referendum will reorient the list of families that control the national pie by raising a few while sinking others. It shouldn’t be lost to us that those who’ve stashed Sh15 trillion abroad stand a better chance of surviving the storm and snapping up the auctioned assets at dirt-poor prices and entrenching their family capitalism for another generation.

Despite their tenacity, the family business model often tends to undermine its own longevity, profitability and efficiency through political favouritism, succession by unfit heirs, endless feuds, and sleaze, including excessive and unnecessary luxury spending on the company’s tab.

An annual study was released ahead of the 2019 World Economic Forum that shows that globally wealth is consolidating back into the hands of a few, with 26 billionaires owning as much as the lower 3.6 billion people in the world. Combined with declining social safety nets, the family business model remains the short-term cushion and guarantor of social mobility for large swathes of the population.

Family businesses range in size, turnover, ownership structures and profitability, from small roadside stalls to behemoths straddling national boundaries. Despite all the squabbles and relational upheavals, family businesses remain a critical means of wealth transfer and generational transition of wealth, opportunity and income.