Let me tell you a story.

I thought Rosa Parks was an old woman who refused to give up her seat on the bus because she was too tired to stand after working all day.

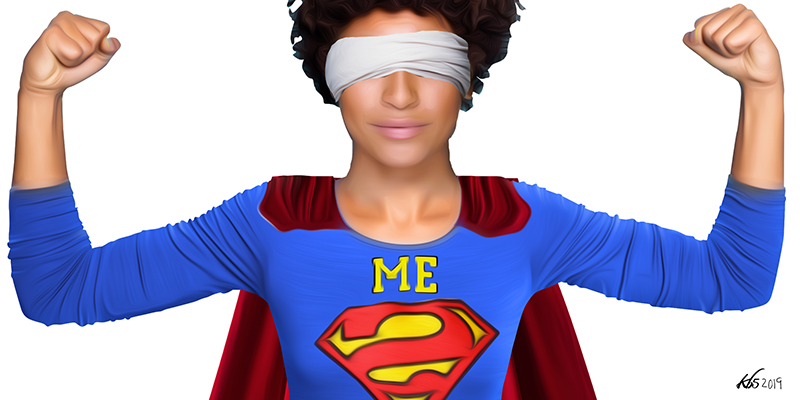

Me too.

I thought Anita Hill, the woman who accused Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas of sexually harassing her when he was her boss, was quite possibly just plain lying.

Me too.

I thought the present-day feminist revolution that is changing conversations around the world was started on Twitter by a white Hollywood actress.

Me too.

Let me tell you a story about the truth behind all those fictions. It’s a story about how the world changed for all American women (and many women in other countries) because of the strength, courage, and integrity of three black women: Rosa Parks, Anita Hill, and Tarana Burke.

On October 15, 2017, Hollywood actress Alyssa Milano tweeted an invitation to her Twitter followers to respond to a suggestion from a friend of hers: “If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me Too’ as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.”

That tweet sparked a response which has indeed become a kind of online census of victimhood. This is the crucial thing to recognise about the moment when #MeToo met social media: that it inaugurated a census. It gave people who had experienced sexual predation a way to stand up publicly and be counted.

Sexual assault and harassment complaints are habitually dismissed when they are made against privileged men, and especially when they are made against powerful men. And the victims who make these complaints are disparaged as attention-seeking, opportunistic, and vengeful.

The accusation of opportunism, in particular, suggests that the accusers believe that going public about having been degraded sexually somehow confers a glorious social privilege upon them (a fiction belied by everything we know about the under-reporting of sexual violence in societies around the world). And the disparagement presents consequences to the perpetrators (if the complainant is believed). Loss of prestige or reputation are viewed as worse than the consequences of the assault or harassment itself, which include the trauma and post-traumatic stress that have for years been recognised as consequences of violence generally, and are now finally being acknowledged as consequences of sexual violence.

Sexual assault and harassment complaints are habitually dismissed when they are made against privileged men, and especially when they are made against powerful men. And the victims who make these complaints are disparaged as attention-seeking, opportunistic, and vengeful.

What #MeToo exposed was not a cabal of vengeful feminists but an ubiquitousness and normalisation of sexual predation, often by powerful and influential men, who are, therefore, socially recognised as more credible than their victims. This choice of victims is not an accident; predators target those they believe will be considered unimportant precisely so that they will be able to discredit any complaints that might be made.

The credibility of complaints is attacked on the grounds of the complainant’s race, social status, national origin, and most especially—when the perpetrator is male and the victim is female—on the basis of gender. Even today, as the United Nations identifies gender equality as one of its significant Sustainability Development Goals, in most countries, women’s voices are not accorded as much credibility as men’s voices in law courts, in police stations, and in public discourse.

Individuals who choose to behave in predatory ways are sheltered from the consequences of their behaviour by widespread beliefs that women lie about being victimised. In fact, because of social shaming around women’s sexuality, women are more likely to stay silent about things that did happen rather than to manufacture things that did not happen.

Predatory individuals are sheltered by the suspicion that allegations of this kind are likely to be false. In fact, the rate of false reporting of, for instance, rape allegations is about the same as the rate of false reporting for other felonies. In addition, predatory individuals are sheltered by demands for “objective proof” that are not demanded in other types of criminal accusations. In fact, a victim’s accusation of fraud, theft, or other forms of violence is sufficient to trigger an investigation, and multiple accusations are sufficient to establish a pattern of behaviour on the part of the perpetrator that is considered circumstantial evidence of their wrongdoing.

Victims of sexual predation know these differences; fear of not being believed is the primary factor explaining why only about 35 per cent of sexual assault cases in the United States are ever reported (which is actually relatively high when compared to a country like Japan, where the reporting rate is estimated to be under 5 per cent). The #MeToo social media census was a space in which victims could self-identify without being invalidated.

But before there was Alyssa Milano’s call to stand up and be counted, there was more than a decade of grassroots activism and solidarity with sexually abused African-American girls that was being carried out by Tarana Burke, the civil rights activist and community organiser who coined the term. There was “Me Too” long before there was #MeToo. There was a black woman, this black woman, doing anti-sexual assault work and victim support long before there was any widespread public discussion by white liberal feminists of the problems of sexual entitlement and predation by wealthy and powerful men. This trail-blazing by black women is also not an accident.

The civil rights movement and the struggle for women’s rights

There is a long history in the United States of advocacy for women and struggles for women’s rights to control our own bodies. That history is grounded in the community organising that black women have done for and with each other, and it has gone largely unrecognised until quite recently.

In 2010, historian Danielle L. McGuire wrote a book about how the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s that is now most closely associated in the popular imagination with Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. owes its existence to the tireless work of black women in the southern states against racialised sexual violence. McGuire’s book, At the Dark End of the Street, documents the campaigns and community organising of black women working in churches and with the venerable National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to demand equal justice under the law for black women who had been raped and sexually terrorised.

There is a long history in the United States of advocacy for women and struggles for women’s rights to control our own bodies. That history is grounded in the community organising that black women have done for and with each other…

One such campaign, directed by the NAACP, was organised to demand the arrest and trial of the seven white men who were responsible for the 1944 gang rape of an Alabama woman named Recy Taylor. The newly-hired NAACP branch secretary who organised the campaign was Rosa Parks. Eleven years later, the advocacy alliance she helped to form, the Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor, would become the Montgomery Improvement Association, the support organisation for the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott that launched the civil rights movement.

Contrary to the mythology that constructs this society-changing coalition as Dr. King’s heroic challenge of white supremacy, it was a movement built by black women like Rosa Parks. She was no tired old woman the day she refused to give up her seat on the Montgomery bus; she was a trained and accomplished activist. And although Recy Taylor never did get justice for the sexual violence she endured, the principle Rosa Parks was fighting for—that sexual violence against black women should be treated as seriously under the law as sexual violence against white women—was finally upheld as a legal precedent in 1959 when the four white rapists of Betty Jean Owens in Tallahassee, Florida were convicted and sentenced for their crime against her.

Almost 50 years after black women mobilised communities across the South to petition for Recy Taylor’s right to face her attackers in court, a black woman named Anita Hill testified in front of an all-white, all-male panel of US Senators in the nation’s capital, Washington DC. The men were there to confirm conservative black judge Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court seat that had been vacated by the retirement of civil rights icon Thurgood Marshall. The woman, a law professor, was there to inform them that when she had worked for Thomas a decade previously at the US Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, he had engaged in sustained sexual harassment of her that called into question the good character which, due to his inexperience on the bench, had been cited as the primary evidence of his overall fitness to serve on the highest court in the country’s legal system.

The year was 1991. The term “sexual harassment” had been coined by the feminist movement back in the 1960s but it was not a widely understood phenomenon in 1991 and there was, at the time, little appreciation for how pervasive it was in workplaces. As law professor and critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw notes in a 2018 New York Times op-ed, it was Hill’s testimony of Thomas’s persistent pressure on her to date him, his discussion of explicit pornography he liked to watch, and comments about his own sexual prowess—all taking place in the offices in which she served as his assistant—that produced America’s “great awakening around sexual harassment”.

However, as Crenshaw also notes, the lessons Anita Hill’s testimony might have taught the country were inadequately learned: Thomas was confirmed to the Supreme Court where he serves to this day, alongside fellow alleged sexual predator Brett Kavanaugh. Hill, in her own 2019 New York Times op-ed, suggests the intriguing possibility that what we now know as the #MeToo movement could have started as far back as 1991, if only that Senate Judiciary Committee panel had listened seriously to her testimony (and that of the corroborating witnesses they never bothered to call).

In the wake of Anita Hill and in the tradition of Rosa Parks came the response of Tarana Burke to a 1997 conversation with a 13-year-old black girl who confided that she had been sexually abused. As “Me Too” broke into the American popular consciousness in October 2017, Burke recalled to a New York Times reporter that this confession had left her speechless and troubled. Having worked with and advocated for marginalised young women since she was a teenager, she belatedly realised that the most appropriate response she could have given the girl was quite simply “Me too”.

Almost a decade after that moment, in 2006, she created a movement to marshal resources for other young victims of sexual harassment and assault—resources she wished had been available to her and to the 13-year-old girl who had called her to this particular strand of her life-long activism—and began promoting the phrase “me too” as a way of raising awareness of the pervasiveness of sexual violence, and as a way of supporting survivors of that violence.

However, as Crenshaw also notes, the lessons Anita Hill’s testimony might have taught the country were inadequately learned: Thomas was confirmed to the Supreme Court where he serves to this day, alongside fellow alleged sexual predator Brett Kavanaugh.

The black roots of “Me Too” are, I think, crucial to understanding what it is trying to achieve, and how. I spoke at the outset of “Me Too” as a census, and I believe that is a useful way to understand how it has functioned in its #MeToo Twitter incarnation. But a robust understanding of “Me Too” as a solidarity gesture has to acknowledge its contextual association with the call-and-response traditions of black music and black vernacular English. Me too is a call and a response: me too … you too?… yes, me too.

Emerging voices

The campaigns for justice and respect to which Rosa Parks, Anita Hill, and Tarana Burke have all contributed their efforts to make a world in which black women are honoured members of their communities have changed things. There is more bodily autonomy for all women in the United States today (challenged and under threat, to be sure, but present). There is more awareness of what it means to have to navigate a “hostile workplace”, and there is more support for the women and men, girls and boys, who have been harmed by sexual violence.

Even as these women are being acknowledged for their courage and dedication, however, and even as black feminist scholarship strives to make sure the contributions to American life of other black women—Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Ida B. Wells, Anna Julia Cooper, to name only a few—are not forgotten, it is important to remember that the tradition of black activism in the US is a communal one.

In the New York Times interview about her role in the Me Too movement, Tarana Burke dismisses the initial controversy about Alyssa Milano hijacking her movement and erasing her contribution by tweeting a “Me Too” invitation that did not credit Burke, saying that it is selfish to frame a movement around one person. Movements should be about amplifying the voices of the community, the survivors, she concluded. (And it should be noted that Milano, who had initially been unaware of the origin of the phrase, swiftly corrected her oversight and has subsequently been vocal in promoting Burke’s Me Too campaign.)

Similar sentiments about the plurality of sources for activist movements and the value of horizontal (non-hierarchical) organising structures are expressed by Alicia Garza in connection with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in a 2016 New Yorker article. The article is a fascinating analysis of how Black Lives Matter emerged as a voice for racial justice from a self-consciously intersectional point of view. It reminds readers that we all engage the world through multiple identities (race, gender, age, sexual orientation), and makes space for Garza’s argument that effective activism to make American society less hostile towards black lives needs to foreground not just a commitment to “unapologetic blackness” but also to an “unapologetically queer” focus. (She notes, for instance, that of the 53 recorded murders of transgender people between 2013 and 2015, 39 were African-American.)

Author Jelani Cobb contrasts the history of black organising in the 1960s, with its emphasis on top-down leadership, with the more diffuse structures of BLM: the three black women often credited with creating it—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi—are carefully distinguished as architects of BLM’s online organisation, while credit for the movement that arose out of protests over Mike Brown’s 2014 murder in Ferguson, Missouri, is given to DeRay Mckesson, Brittany Packnett, and Johnetta Elzie. But, as Garza notes, BLM is not about consolidating power in an identifiable leadership hierarchy; it works like traditional labour organising did, and like Ella Baker (the civil rights activist who served in leadership in both the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) did, it reaches out to the people “at the bottom”, tapping the creativity and energy of the whole community.

The story we need to be hearing and telling, then, in this age of “Me Too” is not just about black women’s leadership, but about the tradition of leadership deeply embedded in black women’s community activism. The power is in the people, and the people need to be heard. Call and response.

The civil rights movement is (mis)remembered as a movement of black men for racial equality; Black Lives Matter is perceived in the media as a redress movement organised exclusively or predominantly around black men murdered by a systemically racist policing structure. In both cases, men’s names are foregrounded in activist histories that have been built up out of women’s labour and include women’s experiences. (Sandra Bland, say her name.)

As we tell the story of Me Too, let’s not forget or overlook the centrality of black women’s struggles for control over their own bodies in the evolution of contemporary activism against rape culture.