The last opinion polls have been published and the final rallies announced for Saturday 5th August. The long, painful political race in Kenya is almost over. It is time therefore to produce my third and final review of events since mid-July and my eve of poll prediction of the results in the upcoming general election.

As with the first two pieces, this is a not-for-profit work, which does not campaign for any party or make value judgements about either’s fitness for office. I am not perfectly neutral of course. Having made a series of predictions over the last year, I may be too embedded in my own thinking and place more weight on evidence that supports my previous opinion than that which contradicts it. Only time will tell. It is based on the idea that things will carry on much as before over the last few days before the poll, and that there will not for example be a major terrorist incident or the death or injury of a senior politician. In such situations, all bets are off.

So, where do we stand at the presidential level? The lacklustre Jubilee campaign improved from May 2017 onwards, but still seems – as I said in June – “strangely unconvincing”. They have “poured” less money into the campaign than expected, though this is changing in the last few days with a centrally organised mobilisation using county assembly members (MCA) to cement their homelands and get the vote out. Jubilee as a party has barely campaigned in the national media, instead using cabinet secretaries and state media to sell its achievements and focussing most of its party campaigning messages regionally. Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto have been dispatched on a punishing schedule nationwide for the last two months, most of their messages focussing on local development and jobs for local communities, but with a subtext of “we may not be perfect, but we have delivered some things, and better the devil you know than the devil you don’t”. In the last two or three weeks, the drift to NASA has stopped and their respective vote shares have stabilised. There are fewer and fewer “undecideds”. There is confidence in the Jubilee campaign, but they remain jittery and there seems a consensus that their campaign has been poor.

However, [NASA’s] main “bandwagon” strategy – that they can and will win – has been undermined by their repeated claims of election rigging by or through the IEBC, of which there have been more than 30 during the last 12 months.

The NASA alliance meanwhile has continued to campaign effectively and appears to have matched Jubilee financially, though they are apparently running short of money in the last few days. Their criticisms of state corruption and high food prices and promises of greater inclusion resonate with many (though they also discourage others for whom inclusion means an ethnic affirmative action programme). However, their main “bandwagon” strategy – that they can and will win – has been undermined by their repeated claims of election rigging by or through the IEBC, of which there have been more than 30 during the last 12 months. Some have been genuine and valid concerns, but many others have not. NASA now have a poor reputation for accuracy and have made several potentially unwise and incendiary statements. While many in NASA genuinely believe they will win, it seems some are preparing to demand power-sharing and negotiated democracy when they lose, using their history of allegations and the events of polling day to demand that Western powers intervene.

There have been several more opinion polls since my last piece, but the key ones were both published on 1 August (the last day that polls are permitted under Kenyan law). IPSOS’ results matched closely their July poll: a 3- point lead for Kenyatta by 47% to 44%, with 8% still undecided, refused to answer or not voting. Reapportioning the undecideds, this gives Uhuru and Ruto a 52% to 48% lead. Infotrak’s poll produced a tiny lead for Odinga by 50% to 49%, but the normal methodology for the poll was absent. TIFA and Infotrak also produced several county-level polls during the period (on Nairobi, Embu, Mombasa and Kakamega amongst others). Although these are less reliable and some may have been “tweaked” to favour particular candidates, they still provide useful data at county level (if taken with a pinch of salt).

The alliances also use their own resources to poll voters, trying all the time to hone their message and focus in on swing voters. Whilst voter targeting through social media platforms is less sophisticated than in western markets (and much cheaper to buy), it is in use in Kenya. Jubilee have spent significantly on Google, Facebook etc both in advertisements and sponsored links. Unfortunately, social media has also been the platform for delivery of an unprecedentedly high level of fake news, with anonymous identities used to seed fake videos, opinion polls and agreements between politicians into Twitter, WhatsApp and other loosely networked platforms which persuade a few that they are true (cementing prejudices they already had) but are also picked up by the mainstream media and thereby have a secondary impact. The widespread use of fakes and lies in the campaign by both sides has further brought into question the probity of Kenya’s political class.

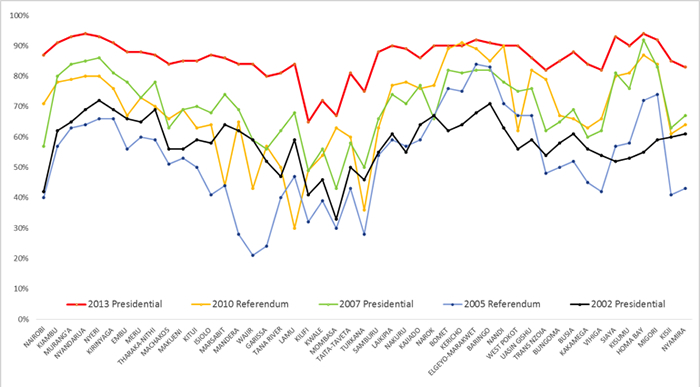

The size and scale gap between 2013 and every other election for the past 15 years is hard to explain. So, building a turnout model based on 2013 and adjusting for changes since then risked building in rigging to the prediction.

Regionally, there has been modest “churn” – no county or community has switched sides entirely, but some have moved one way, some the other by a few percentage points. It appears that NASA are indeed stronger in Meru than I assessed in July (though Jubilee will still win easily), and have cemented their hold on the Maasai vote, but Jubilee is stronger in Bungoma and Bomet. There have been few public defections by significant political players, and the agreements stitched together by both alliances with small parties to support one or other’s presidential bid have all held firm.

Predicting the Presidency

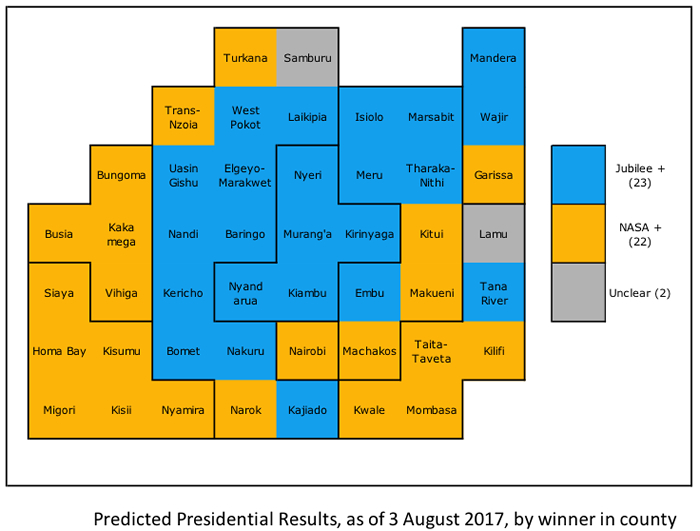

Trying to improve on my presidential prediction model, I have made a dozen or more changes in vote share predictions in response to the opinion polls, significant rallies and other less tangible factors. I’ve shifted Nairobi even further towards NASA (now 55% for Odinga, 44% for Kenyatta), though I think it will be closer than recent polls suggest. In Machakos, Bungoma, Trans-Nzoia, Migori and Bomet I’ve upped the prediction of Jubilee’s performance, but reduced it in Narok and Kajiado (though Jubilee may still win Kajiado because of the non-Maasai population), Kiambu (parts of which are now a multi-ethnic suburb of Nairobi), Turkana and Meru. The strength of the internal insurgencies in Bomet (Isaac Rutto) and Machakos (Alfred Mutua) remain some of the great imponderables, with public and private polls giving contrary results and few sure of the outcome. Opinion polls are also giving Odinga more support among the Somali of Mandera, Wajir and Garissa than an examination of the parties’ candidates and the history of negotiated democracy between Somali clans and sub clans would suggest.

I still predict a Jubilee victory by 52% for Kenyatta and Ruto to 48% for Odinga and Musyoka, with all others less than 1% combined. On a 76% turnout, that would be just under 8 million votes for Jubilee and just over 7 million for NASA.

The other change made to the model is more significant. For some time I have been wrestling with an ethical problem. Reviewing the 2013 turnouts, in comparison with that from previous national elections since 2002, it became clear with the benefit of hindsight that turnouts were implausibly high not just in Luo Nyanza and Central Province, but in many other places. Even given the greater attention and sensitivity around the 2013 polls, the suspicion is that both parties found ways to pad their vote, and that this happened in many places. The graph below shows the turnout by county for every national presidential election or referendum since 2002, with 2013 bolded in red. The size and scale gap between 2013 and every other election for the past 15 years is hard to explain.

So, building a turnout model based on 2013 and adjusting for changes since then risked building in rigging to the prediction. It might be more accurate – because if they have done it before, they may find a way to do it again – but it’s not right. So, instead I have changed to a weighted average model of turnout in the last five national contests: the 2013 presidency, the 2010 constitutional referendum, the 2007 presidential election, the 2005 constitutional referendum and the 2002 presidential election. Three of these are generally accepted to have been “free and fair”. The new model is weighted because it takes 50% of its prediction from 2013, 25% from 2010, 12.5% from 2007, and 7.5% from each of 2005 and 2002. The result of applying this change is that predicted turnout drops sharply, though it continues to follow the same national pattern (Central Province and Nyanza the highest, Coast the lowest).

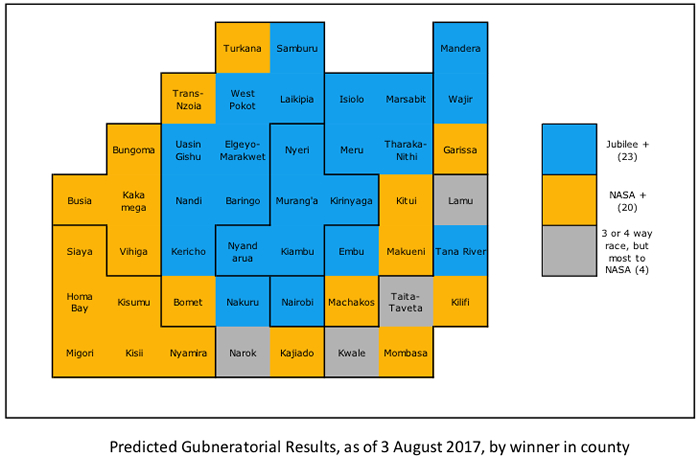

To my surprise, when reviewing the IEBC list of gubernatorial candidates, there are 13 counties were NASA has not put up a candidate from any allied party, already conceding the seat to Jubilee and potentially depressing the Odinga Presidential vote there. There are only two (Makueni and Vihiga) which Jubilee has similarly conceded.

Putting it all together, the predicted result has changed since July, but not by much. I still predict a Jubilee victory by 52% for Kenyatta and Ruto to 48% for Odinga and Musyoka, with all others less than 1% combined. On a 76% turnout, that would be just under 8 million votes for Jubilee and just over 7 million for NASA. This assumes that the new IEBC technology delivers at least some of what it promises, by preventing the dead from voting and clerks from voting for absent voters after the polls close.

Note: one box is one county, whatever its geographical or population size.

Around the Counties

Turning to the counties and the Gubernatorial races, there have been few surprises, except for the inability of either side to get their defectors (standing as independents or as candidates in allied parties) to stand down. The pressure now to do deals will be intense and several more will retire over the weekend. NASA still risks losing the governorship in one or more of Taita-Taveta, Kwale, Lamu and Narok due to split votes (though they solved their problem in Machakos). There is a tension here, as intense local competition within an alliance pushes up the Presidential vote for their side, while it risks a split vote and losing the seat at county level, which partly explains the ambivalence of both party leaders in addressing the problem. I still predict that Mike Sonko will win Nairobi, narrowly but Peter Kenneth’s persistence despite entreaties from Uhuru, and his 3-5% support base might allow Kidero to be re-elected on a split pro-Jubilee vote. Most of my other predictions remain unchanged, though KANU is putting up a decent showing as the only real opposition to Jubilee in the North Rift, and in Western the situation is increasingly confusing as ANC, ODM and FORD Kenya take on each other as much as Jubilee. I’m predicting Wamanagati (Ford Kenya) to take Bungoma, Otuoma (pro-Raila independent) Busia, Oparanya (ODM) Kakamega and Chanzu (ANC) Vihiga. To my surprise, when reviewing the IEBC list of gubernatorial candidates, there are 13 counties were NASA has not put up a candidate from any allied party, already conceding the seat to Jubilee and potentially depressing the Odinga Presidential vote there. There are only two (Makueni and Vihiga) which Jubilee has similarly conceded.

Overall, my final prediction is 24 Governorships for Jubilee and its allies (including KANU, FAP, PDR, EFP, PDP, PNU, MCC, NARC-Kenya and pro-Uhuru independents) and 23 for NASA and their allies and independents, a slight improvement on Jubilee’s performance in 2013. Senator and Women representatives will follow a similar pattern, though there will be less ”six piece suite” voting than in 2013, when voters’ had no experience with their roles in the new political structure. But a voter’s choice of ticket is more likely to stem either from their Presidential and Governor preference or from their MCA and Parliamentary choice, less often from their Women’s Rep or Senator.

It is the constituency Returning Officer who is the formal declarer of the presidential results (as with parliament and MCA), and therefore the electronic results sent direct from polling stations to the screens at the Bomas of Kenya are advisory only.

At the 290 parliamentary constituencies level, it is near-impossible to apply the same level of scrutiny, but at a high level, the pattern is similar. Roughly 54% of parliamentary constituencies look like being pro-Jubilee (including affiliate parties and independents); 46% pro-NASA.

An Uncomfortably “Hot” Seat

The situation for the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) is far from comfortable, tasked with running every aspect of this election under intense and hostile scrutiny. The design of the Kenya Integrated Election Management System (KIEMS), which will be used (for the first time) to capture, check and transfer the polling station results to the counts, looks strong on paper. If the system has been built as intended, it is a robust and effective tool to control rigging and ease results transmission. However, there is still the risk of errors in the IT implementation (which only extensive testing would detect) or security flaws, plus the ever-present risk of human error. And there remain confusions among the public as to whether the electronic results sent from the polling stations or the Form 34 results are the “master” (it is the latter), and whether the court’s decision regarding declaration of results empowered the polling station presiding officer or the constituency Returning Officer to announce the presidential results (again the latter). It is the constituency Returning Officer who is the formal declarer of the presidential results (as with parliament and MCA), and therefore the electronic results sent direct from polling stations to the screens at the Bomas of Kenya are advisory only. If there is a partial or systematic failure in the electronic systems or in the mobile networks (as there was in 2013) forcing some POs to “go manual”, there will be a gap between the (incomplete) automated results displayed and the (complete) official results from scanned and physical form 34s, which will take longer to arrive (being sent by email). The IEBC has decided not to announce constituency results, relying on Returning Officers to do so instead, but the result will be a discrepancy between the real tally and the one displayed on the screen, which could be the source of serious misunderstandings. This could be even more of a worry because the results will trend in favour of NASA at the start (as the urban areas are mostly pro-NASA) and towards Jubilee towards the end (most of the biggest, semi-arid northern counties are pro-Jubilee). Unlike in 2013, when the commission chair repeatedly informed Kenyans that only the paper results were valid and the electronic system just a check on them, the IEBC has been far less clear this time, relying on the mantra that “We do not expect any variances between the forms and the electronic data.”

The IEBC needs to develop and publish protocols for how it will handle various failure scenarios (such as : the KIEMS electronic transmission doesn’t match the scanned form 34; there are two form 34s; the scanned form 34 has been clumsily altered; there is no physical form 34 at all; there is a failure of the electronic system half way through polling) before they actually occur, to reduce the risk that they are accused of ‘cooking’ the results when – rather than if – things go wrong.

The unprecedented level of scrutiny by the courts of the IEBC’s actions during 2016-17 has improved the integrity of the process and public confidence in it, but it has severely delayed the IEBC’s preparations.

Their recent announcement that clerks would no longer mark the register when voters voted electronically was a smart anti-rigging move, as it mean clerks don’t know who voted, and that means they can’t go manual and “fill in” the votes for those who didn’t turn up by closing time (as is suspected to have happened in the homelands before). However, it introduces a new risk – if the electronic system fails midway through the day, then voters who voted in the morning electronically could all vote again in the afternoon physically (if they can get the ink off their fingers), which would cause complete chaos if it occurred on a large scale. Nobody really understands how a mixed mode election might work in a polling station if the electronic systems fail part way through for whatever reason.

The unprecedented level of scrutiny by the courts of the IEBC’s actions during 2016-17 has improved the integrity of the process and public confidence in it, but it has severely delayed the IEBC’s preparations. Despite their public protestations, things are far from smooth and the murder of their ICT head Chris Msando has further stressed an already pressured organisation and brought once more into sharp relief the risks of election rigging at the IEBC headquarters, despite the fact that presidential results will be issued at the constituency level. Conspiracy theorists, of which Kenya is never short, have developed several lines of thought as to why Msando was killed. Few believe his death was unconnected to his IEBC role, but the logic as to why it was done remains impenetrable. Hard-line elements in Jubilee (or the security services) are the main suspect in the minds of many, but Jubilee is the main loser from Msando’s death and the manner in which it occurred, as it strengthened fears about the risk of rigging, deepened speculation about passwords and backdoors into the IT systems, and provided yet more ‘grist to the mill’ for NASA to demand that the election be annulled in the event they lose. The possibility that it was a message to others in the IEBC organisation to follow orders on election day cannot be discounted either.

As well as the IEBC’s own systems and collation activity, several news desks and the main political parties will be running parallel constituency level counts. The ELOG domestic observer group will also be running a parallel vote tabulation, texting in the results from a sample of 1700 polling stations, which should provide a degree of validation (if available in time) for the IEBC’s results. International and domestic are also fanning out across the country this weekend to add their more anecdotal assessments of whether the election was conducted freely and fairly. The situation as the results come in is going to be even more noisy and confused than before, and if fake news is injected into the mix, the cocktail is potentially explosive.

The situation as the results come in is going to be even more noisy and confused than before, and if fake news is injected into the mix, the cocktail is potentially explosive.

Looking at the risk of post-election violence, it is near certain that there will be trouble somewhere, but it is unlikely to occur with the ferocity and scope of 2007. The security forces are far better prepared, and the continued alliance between Ruto and Kenyatta and Kikuyu and Kalenjin neutralises the fault line with the greatest potential for trouble. But there will be violence in Nairobi, Kisumu and elsewhere as the results come out if NASA have lost or if the electronic systems fail early on (few have considered a situation where the security forces are called out to respond to mass violence by pro-Jubilee youth if they are defeated). Much depends on how far the loser’s leaders are willing to go. The two key factors influencing the likelihood of trouble are the size of the winning margin for the victor and the success or failure of the IEBC in administering the election effectively, without obvious rigging. If the election is well run, turnouts and results reasonable and the margin of victory 5% or more, there will still be complaints and localised demonstrations, but they will be modest and limited. If the result is within 2% (i.e. 51%-49%) or the election proves an administrative mess and rigging is visible and widespread, the risk of trouble on 10-11 August rises dramatically. While the losers have the option to escalate to the Supreme Court through a petition, the opposition’s attempt in 2013 was unsuccessful, hamstrung by the short timeframes and burden of proof, and they are indicating an unwillingness to take that route again, in which case mass action and street violence is quite likely.

If the result is within 2% (i.e. 51%-49%) or the election proves an administrative mess and rigging is visible and widespread, the risk of trouble on 10-11 August rises dramatically.

For now, having published this prediction, I have to step back and stand or fall by it. In a strange way, if I am proved wrong, this will be good news for the country, as it will demonstrate that the old rules of “bribe and tribe” no longer dominate Kenya’s politics. Whatever the result, I wish you all the best and look forward to seeing you all “safe and sound” on the other side.