Are East African countries ready to face the next crisis or are they simply keen to go back to how things were? What does a new normal mean when speaking about public finance management (PFM)?

In continuing the struggle for structural transformation, economic justice efforts must work towards developing a new citizen and preparing for unpredictable or unforeseen events, more so those with extreme socio-economic and political consequences.

This is because, besides known challenges posed by existing inequalities, the COVID-19 pandemic has pointed out how “unusual circumstances such as man-made disasters, natural catastrophes, disease outbreaks and warfare … depress the ability of citizens to engage in economic activity and pay taxes as well as that of governments [capacity] to collect revenue [or] provide services”.

Such circumstances therefore demand more inclusion of human rights-based approaches in economic justice efforts to champion greater fairness within existing financial architecture.

Disasters should, therefore, not obliterate human rights but should heighten the need to respect, protection, and fulfilment of obligations through prioritizing expenditure on service delivery, as well as all elements of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ESCRs) to “boost the capacity of residents to withstand shocks” by improving coping mechanisms.

Promotion of fair taxes among other broader economic justice initiatives within PFM should consequently adapt towards championing ESCRS within the context of more disruptive and unexpected incidents. Crisis is constant in the new normal.

Fiscal democracy and civil protection: Recovery, resilience, and transformation

Currently, conversations on recovery are focused on tackling reduced tax collection; slowed growth; depressed formal or informal productivity; exploding unemployment; diminished remittances; persistent poverty; decline in energy access; and escalating food insecurity.

This emphasis seeks to reverse the effects of various lockdown policies that placed restrictions on businesses, mobility, movement within and across international borders, [plus] public gatherings. However, it speaks mostly of a desire to return to pre-COVID levels of economic activity while vital systems in tackling the next crisis such as water, education, or health remain unaddressed.

Economic justice initiatives should therefore embrace fiscal democracy and civil protection as goals or appendages in achieving the structural transformation agenda. This will then speak to the resilience, and transformation needed to ensure PFM works for Africans in good times or bad.

Understanding fiscal democracy takes the form of better prioritization, response to problems, and improved sanctions for mistakes in the revenue cycle.

Advocacy for increased domestic opportunities, promotion of childhood development, enhanced socio-economic mobility, support for workers, motivation of local entrepreneurship, diversification of public infrastructure from mega projects, as well as increased innovation through subsidized research and development should be at the heart of economic justice efforts.

Economic justice initiatives should therefore embrace fiscal democracy and civil protection as goals or appendages in achieving the structural transformation agenda.

Civil protection gives a new framework of planning by envisioning contexts or processes in which a series of unfortunate events can emerge, thus providing adequate responses without breaking the social contract.

Transformation therefore occurs when both go hand in hand so that public facilities are not overstretched in the event of crisis. Hence, in looking at the impact of Covid-19, across the East Africa region, we must ask ourselves: How transformative are the current recovery efforts underway? Will they offer a new resilience?

The salvage job: Economic sustainability through reliefs, guarantees, subsidies, and funds

Responses have clearly been driven by the urgency to overcome the pandemic and the need to forestall outright disaster or collapse. The “short-term rescue mode” has seen efforts to ensure vaccine access and bolstering of public health systems.

On the economic front governments “Have sought debt relief, implemented corporate tax deferrals plus exemptions, made direct citizen transfers and interest rate adjustments. [They have also] implemented guarantees and subsidies, liquidity support and food relief … [with] examples of support for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Cash transfers and other safety nets for poor and vulnerable populations are critical for an integrated … response. While not transformational, they are building blocks for a basic level of resilience to external shocks.”

The fact that these efforts are not transformational must motivate the infusion of a justice quotient in recovery efforts. This will enable a movement beyond an emergency-oriented recovery that recognizes existing modern challenges such as climate change, population growth, scarce resources, man-made or natural calamities.

In the case of tax justice, to make the linkages that will establish economic sustainability in East Africa, it is important to understand the effect of recovery efforts in relation to public debt; the tax burden on individuals or households; illicit financial flows; harmful tax practices; economic growth; and resource distribution.

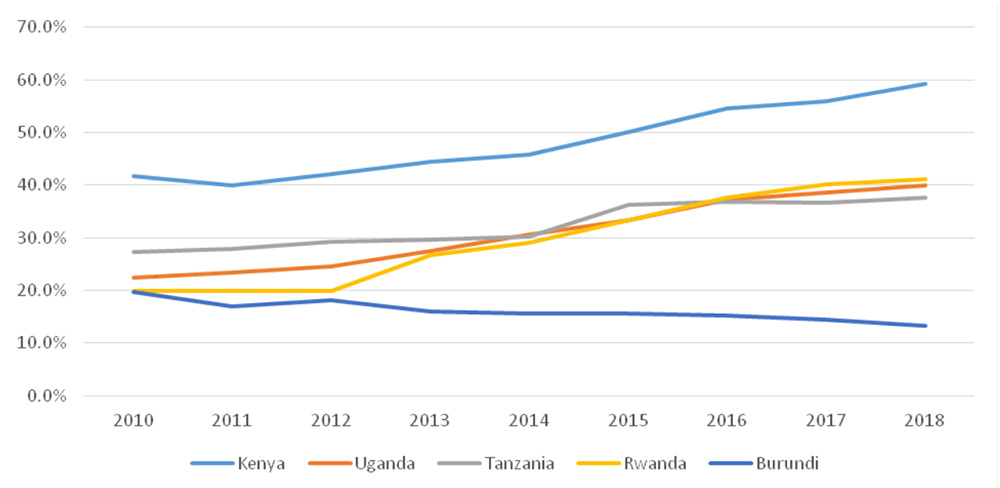

Recognizing the prevalent debt crisis even before the pandemic struck is important in informing economic justice movements and their activities. Concerns were looming over the fact that 40 per cent of Sub-Saharan African countries were in or at high risk of debt distress. Between 2010 and 2018, public debt in East Africa grew rapidly as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – National Debt to GDP Ratio

In this time, East African Community (EAC) governments failed to mobilize sufficient revenue despite an overall increase in taxes. The situation was therefore exacerbated by COVID-19, the consequence being that these countries are now stuck in a situation where they must tax more to bridge revenue gaps.

Basically this, first and foremost, creates a context of unfair tax policies in the region that burden their respective citizens, does not enhance service delivery, and is exclusionary in how debt repayment strategies are developed.

Lack of open debate about a country’s fiscal priorities within the existing PFM system neglects the needs of youth who constitute the majority of the population among other segments of society, curtails ideas on how to increase resources needed to provide for new economic opportunity(ies) and respond to the next emergency.

Recognizing the prevalent debt crisis even before the pandemic struck is important in informing economic justice movements and their activities.

Secondly, an environment or ecosystem of illicit financial flows (IFFs) that constitutes the formation of International Financial Centres (IFCs) in Kigali and Nairobi plus the signing of numerous Double Taxation Agreements (DTAs) continues to perpetuate itself thereby providing loopholes within the tax architecture that undermine efforts at domestic revenue mobilization (DRM) because the monies going out of countries are so massive, outweighing Overseas Development Assistance (ODA).

This is thanks to “Constitutionalism [among other legal questions] plus demands to implement new public finance management principles, growth in trade and services across countries in the region or with other countries across the globe, and discovery of natural resources requiring more inflows of foreign direct investments (FDI).”

On average IFFs accounts form 6.1 per cent of Sub-Saharan Africa’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) thereby impeding economic development and sustainability. For instance, since 2011, Kenya is estimated to lose KSh40 billion annually “as government, local firms and multinationals engage in fraudulent schemes to avoid tax payments”. As of 2021, The State of Tax Justice Report indicates this has grown to an estimated KSh69 billion annually at current exchange rates.

Third, growing account deficits and rising external debt are heavily limiting to economic growth. Increased spending on debt repayment is restricting prioritization on essential public goods and services while borrowing remains one of the key sources of budget financing.

In as much as Kenya cancelled its recent pursuit of another Eurobond, the about-turn towards borrowing domestically following a surge in yields within international markets because of the Russia-Ukraine war is still going to punish the country’s citizens by squeezing them out of access to credit.

Lastly, the debt burden is disempowering the citizen. Rising public debt may result in poor public participation in the management of fiscal policy, and weak structures for keeping governments accountable. This is further worsened by limited access to information on debt or public spending. Moreover, there is weak oversight by parliaments as executives take full control of processes.

Policy-making processes during cascading crises: Fiscal Consolidation, Special Drawing Rights, and Open Government

By understanding that crisis is constant, and that it is likely to manifest as confluence events — merging risks of mitigatable disaster(s) — or major confluence events, that is, the combination of potentially unmitigated risk(s) at any one point in time, how does policy making at such a time help to prepare for the emergency next time?

For example, what does Kenya’s fiscal consolidation programme — which comprises of reforms to improve oversight, monitoring, and governance of state-owned enterprises; improved transparency of fiscal reporting; and comprehensive information of public tenders awarded including beneficial ownership information of awarded entities — have to do with preparing for the next series of cascading crises?

Several emergency relief funds have been established to address the impact of COVID-19, such as the Rapid Credit Facility, the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust, and the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI).

However, these efforts are not likely to unlock the existing “trilemma” of solving the health plus economic crisis and meeting development targets while dealing with a tightening fiscal space. This is because they are stuck in the present circumstances with no consciousness of how much the challenge is likely to prevail into the future.

East African Community governments, in this time, failed to mobilize sufficient revenue, despite an overall increase in taxes.

Adopting fiscal democracy not only provides a new agenda determining organizing principles, but it has the potential for establishing a new citizenship through further entrenchment of human rights-based approaches in economic justice, and commitment to open government principles.

It will also anticipate and prevent the disaster capitalism witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many African countries seem to be in a constant state of crisis, thus allowing for IFFs through PFM malfeasance that locks corruption and fraud into procurement through bid rigging or collusion.

Principals of public participation, demands for accountability, championing non-discrimination, advocacy for empowering programing, and legitimacy through the rule of law should set standards on beneficial ownership while open contracting, open data for development, legislative openness, improving service delivery, access to information, and access to justice will help build resilience in government.

A call to civic education: Revenue rights and obligations

Somewhere along the way, capacity building and training programming took prominence over civic education. Advocacy efforts should look for ways to bring back more popular public awareness. Denial of resources for these kinds of activities has been a major blow for PFM advocacy among other activist efforts.

Civic education will re-establish links between individual claims to service delivery and assigned duties in the fulfilment of public demands. Citizens will be able to identify how the problem manifests and engage on the immediate, underlying or root causes of an issue.

Rising public debt may result in poor public participation in the management of fiscal policy, and weak structures for keeping governments accountable.

It will also allow them to establish the patterns of relationships which may result in the non-fulfilment of rights or absconding of obligations. This will enable them to assign appropriate responsibility by identifying the relevant authorities. It will keep an eye on resources through participating in decision making.

Governments and political leadership should therefore work to improve their communication capabilities in engaging the public so that once this new citizenry is involved, they can work together to achieve representative priorities for action.

–

This article is based on a presentation and comments made at the African Forum and Network on Debt and Development (AFRODAD), Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Debt Conference, Towards strengthening accountability and transparency around public debt management and the use of IMF Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) in Eastern and Southern Africa, 20–21 June 2022, Nairobi, Kenya.