When William Ruto unleashed his new rallying cry, campaigning to mobilise support for his vision of a “hustler nation”, public attention focussed on the “hustler” part of that phrase. Since then, both social and traditional media has been awash with talk of hustlers and their supposed opposites – privileged dynasties. Much less attention has been paid to the second part of that famous phrase: the hustler nation. Yet in Ruto’s attempt to be seen as an inclusive leader willing to govern in the interest of all Kenyan hustlers, that word does just as much work.

“Nation” is a weighty word. Sixty years ago it helped bring an end to colonial rule across Africa. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century history had weaponized “nation”, turning the word into an irrefutable claim to sovereignty – nations should govern themselves. A generation of African politicians turned that power against European rule with dramatic results: they were nationalists, their goal was national freedom – and they triumphed.

After political independence, Africa’s new rulers found themselves in a global system that made nationhood an obligation as well as a claim: national flags, national anthems, national holidays – every government had to have these. The very word “international” is significant: it insists that the world is made of nations. So powerful was this idea in Africa that it crushed ideas of alternative political futures, both within and beyond the borders of new states. Regional federations and unions were eclipsed by the nation; opposition political parties were suppressed in the name of national unity.

In Kenya, as elsewhere in Africa, the nation was omnipresent for decades after independence. Nationalism became a demand for obedience as well as a statement about unity. Kenya was the nation and it was the task of everyone to build it. Both the title and the slogan of a newspaper created just before independence reminded readers of this fundamental truth, with the ubiquitous legend: “Daily Nation – the newspaper that builds the nation”.

From presidential speeches to chief’s barazas, no public event was complete without a reminder of the importance of nation-building. The name of almost every public institution restated the point, from the National Theatre to the National Cereals and Produce Board. There was only room for one nation in Kenya.

That singularity has slowly slipped away. The 2010 constitution says in its preamble that Kenya is “one indivisible sovereign nation”; President Uhuru Kenyatta still talks of nation building, just as his father did. Yet somehow, without anyone remarking on it, it has become entirely normal to talk of multiple nations across Kenya. Sometimes these nations are avowedly cultural in form: evoked to preserve custom. But more often they are explicitly political, and social media spaces devoted to them tend to fill up with partisan discussion. As the election campaign hots up, nations multiply in cyberspace and calculations of ethnic support and claims-making by politicians and activists are routinely expressed in the language of nationhood.

So now the voting intentions of people who live in western Kenya are discussed in terms of the Mulembe nation; politicians demand that the Mijikenda nation be recognized; commentators chide the Kikuyu nation; and, Maasai leaders assert claims on behalf of the Maasai nation. In this popular whirl of nation-making, the relationship between nations is unfixed: the website of the “Sebei nation” describes it as part of the “Kalenjin nation”.

“National” politics used to mean a relentless insistence on Kenyan unity as a counter to ethnic politics. Now Kenya has a politics of nations that revolves around particular claims by communities. The style of politics is not new, of course: behind the rhetoric of nation-building, ethnicity has always been a way to mobilise and make claims. But how these claims are made has changed, perhaps because since the destabilising violence of 2007/8 major leaders have been wary of making explicit appeals to ethnic sentiment, conscious that this might leave them open to criticism and even, in extreme cases, prosecution. In this new more cautious political age, the word “nation” is used to authorise ethnic politicking.

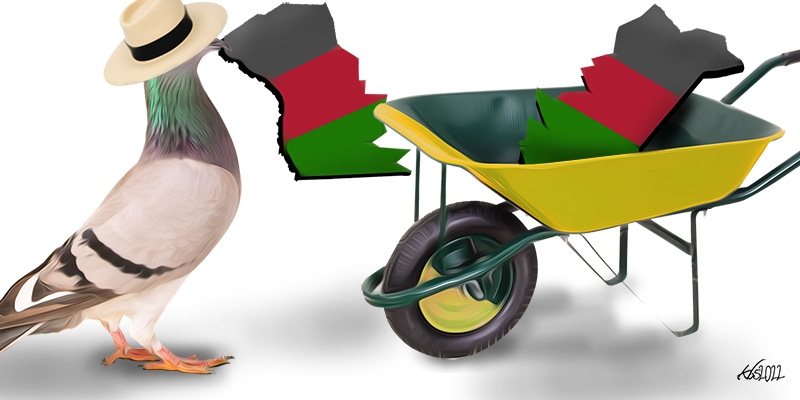

Kenya’s multiplying nations are mostly ethnic – but not all of them. As we have already discussed, the deputy president’s campaign revolves around another new collective – the “Hustler Nation”. That tag gives nation a new meaning – now it is a term that evokes how people make a living, not ethnicity or culture. The Hustler Nation – which also, of course, has its Facebook page – aims to mobilize a sense of economic marginalization as a collective claim.

Behind the rhetoric of nation-building, ethnicity has always been a way to mobilise and make claims.

Ruto’s messaging readily identifies some members of the Hustler Nation: the mama mboga and the boda boda riders, for example. It is less clear about who is not in his Hustler Nation, however – does it embrace everyone? Is it only “dynasties” that are excluded? Or also those who do not seek to work hard – a message that would return Kenya to the political mindset of harambee that characterised the Jomo Kenyatta years? Harambee is, after all, back in vogue as a term, both for Ruto and for Raila Odinga. Sometimes the deputy president still talks about Kenya as a single nation that his “movement” seeks to build on new terms:

“We must be a nation that is equal. . . . This is the Hustler Way; this is the way to change Kenya”.

Raila can also wax lyrical on the singularity of the nation: “We must unite our entire Nation”, as the text of his Jamhuri Day speech put it.

Why have Kenya’s nations proliferated? Kenya is not alone in these competing evocations of nation – the United Kingdom, after all, is chronically uncertain over whether it is one nation or four (or possibly more – Cornish nation, anyone?). Across the world, the word nation has been turned against the nation-states that claimed it – it has become part of the rhetorical toolbox of movements for indigenous rights as well as secessionists. That is part of the word’s pedigree, after all – it has often been a way to challenge the legitimacy of established political orders, which is why Kenya’s nationalists once found it so useful. It’s not surprising that such a powerful word is being turned to new uses.

Does this matter? This change might be welcomed as a sign of political maturity – if the word “nation” no longer requires such jealous guarding, might that be a sign of confidence and stability? And as we have noted, “nation” now stands in for a form of ethnic politicking that was more explicit and hence potentially divisive. But there is also a hazard to the proliferation of nations.

For decades Kenyans have been urged to build the nation and encouraged to think of themselves as having a duty of obedience to national leaders. If Kenya’s nations multiply – and get smaller – that might shrink the space for ordinary people to make political choices and further flatter the egos of politicians who imagine themselves as speaking for their nations. After all, national unity was once valued precisely because it papered over ethnic cracks and fostered unity.

Could creating too many parts undermine the whole? How many nations are possible, after all?

We could look elsewhere in Africa for a lesson here. Ghana, for example, regularly sees close elections and, if one looks at just the data, significant patterns of ethnic/regional voting. Yet the fact that the main presidential candidates largely avoid speaking and campaigning in strictly ethnic terms – and avoid referring to “the Asante nation” or the “Ewe nation” – has helped to sustain the collective (and valuable) myth that what motivates voting behaviour is solely adherence to one of two ideological positions, and the performance of the sitting government.

Kenya’s politicians might have reason to follow suit, because popular attitudes to the proliferation of nations may be more ambivalent than first appears. Although Kenyan politics is often described in terms of an ethnic census, things have never been quite that simple. Communities such as the Kikuyu and the Luhya have regularly divided their vote, and the most dangerous accusation that can derail a politician’s career is that they are a “tribalist”.

As the recent book, The Moral Economy of Elections in Africa demonstrated for Kenya, Ghana and Uganda, politicians can excite their ethnic base by using exclusive and hostile language, but this comes with a cost: they are unlikely to be viewed as “presidential material, undermining any attempt to run for national office – even by some members of their own community. This can be fatal – especially when it comes to the presidential election in countries like Kenya, where successful candidates must now receive 50 per cent +1 of the ballot.

Indeed, many readers may be surprised to learn that the proportion of citizens who say they feel more “ethnic” than “national” has actually fallen over the last decade, despite the fact that Kenya has repeatedly held close and contested elections. According to the nationally representative survey conducted by the Afrobarometer, the share of people saying they only feel an attachment to the “Kenyan nation” has increased from 24 per cent to 43 per cent since 2005 (The question asked is: Let us suppose that you had to choose between being a Kenyan and being a [respondent’s ethnic group]. Which of these two groups do you feel most strongly attached to?)

While it seems unlikely that those participating in the survey don’t feel any sense of ethnic identity at all, the fact that an increasing proportion of people wish to present themselves in this way tells us something important: however many nations exist in cyberspace, many Kenyans wish for a world in which the nation is a singular, unifying concept.

Nation is a powerful word. That motivates leaders’ desire to put the term to political use. But they do so at their peril – stripping the term of its unifying force can help to rally hardliners within a given community, but is likely to be unpopular with the wider electorate once they head to the ballot box.